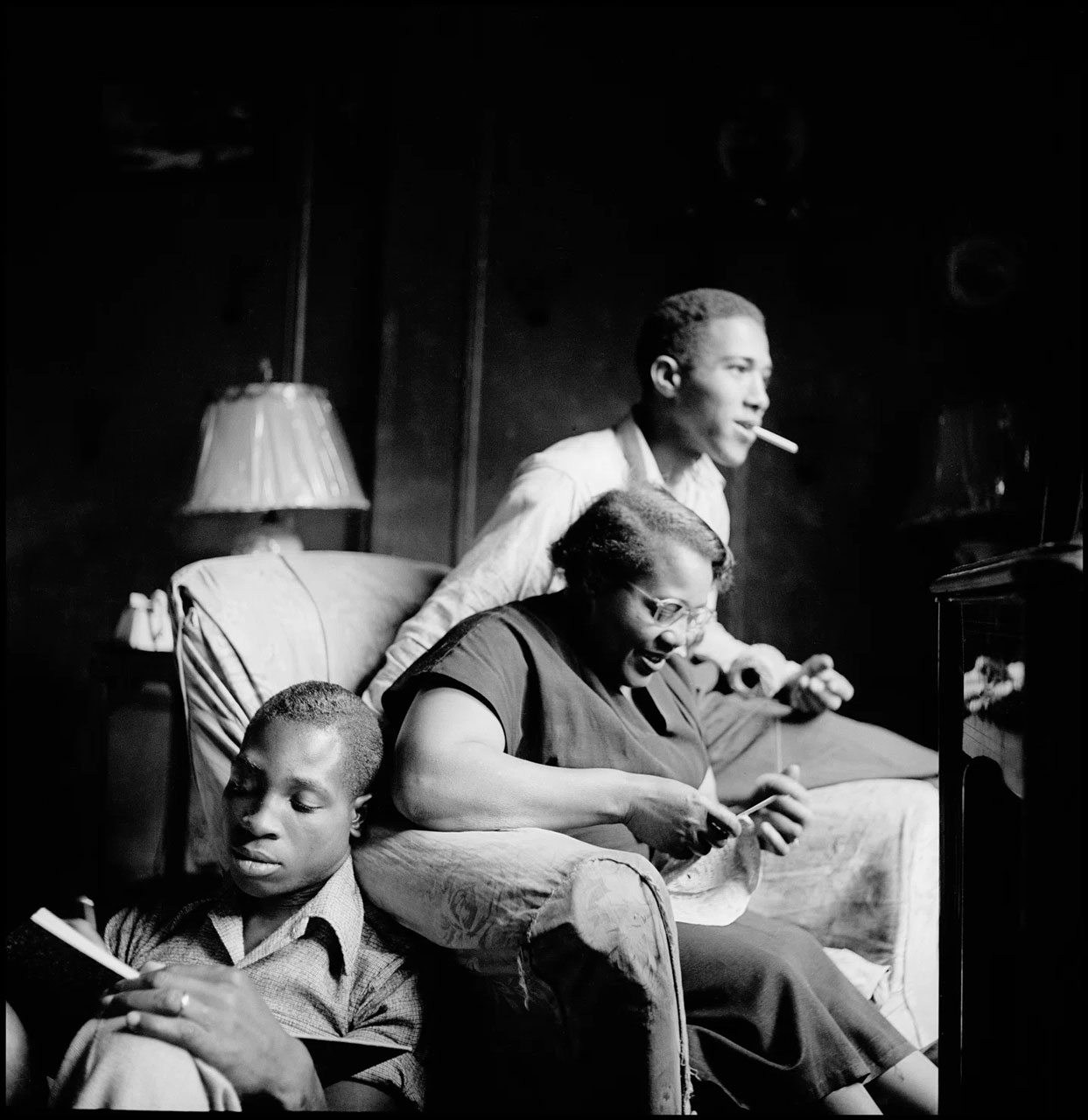

PHOTO: Gordon Parks

In a career that spanned more than fifty years, photographer, filmmaker, musician, and author Gordon Parks created a groundbreaking body of work that made him one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1940s, he documented American life and culture with a focus on social justice, race relations, the civil rights movement, and the African American experience.

In a career that spanned more than fifty years, photographer, filmmaker, musician, and author Gordon Parks created a groundbreaking body of work that made him one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1940s, he documented American life and culture with a focus on social justice, race relations, the civil rights movement, and the African American experience.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Pace Gallery Archive

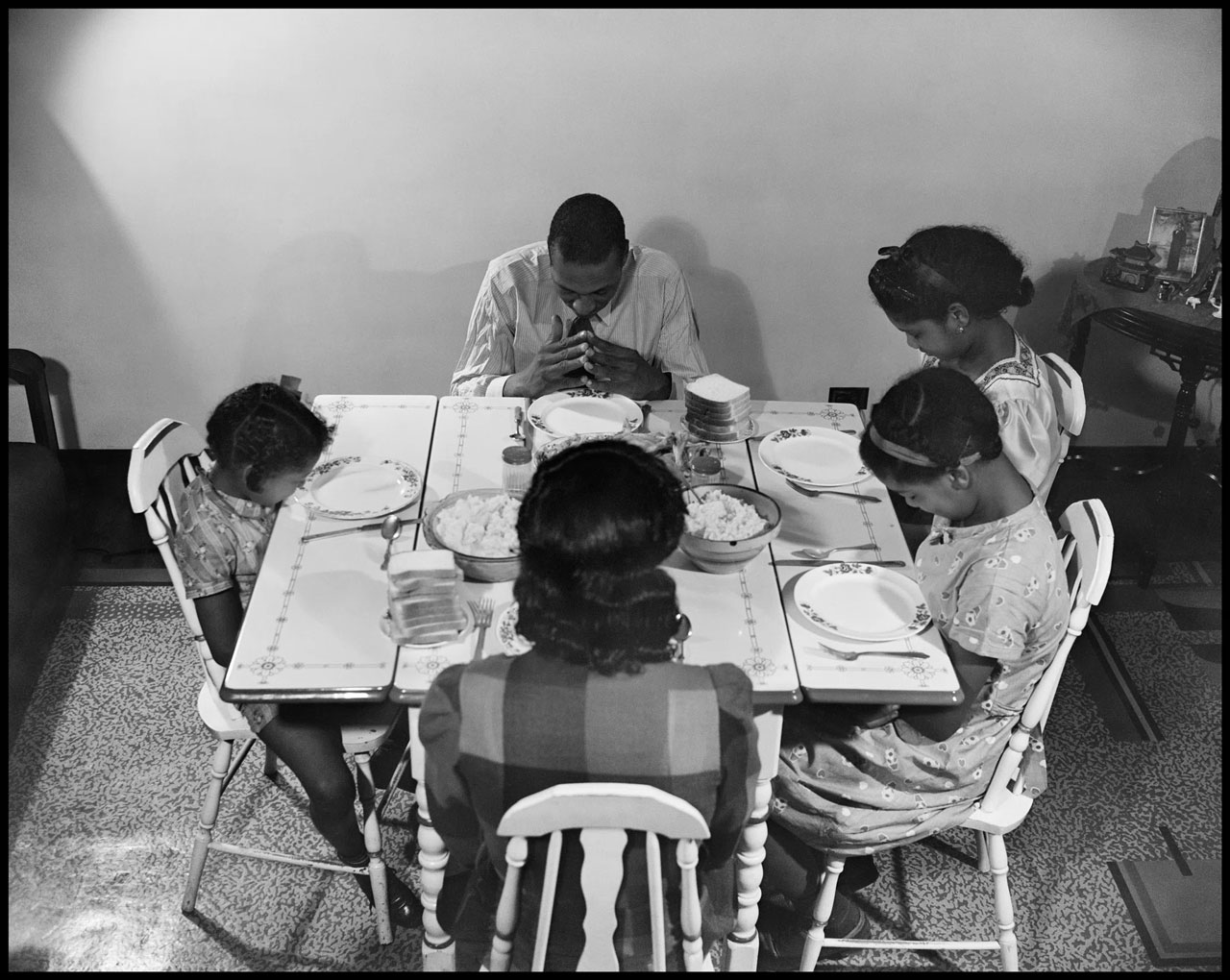

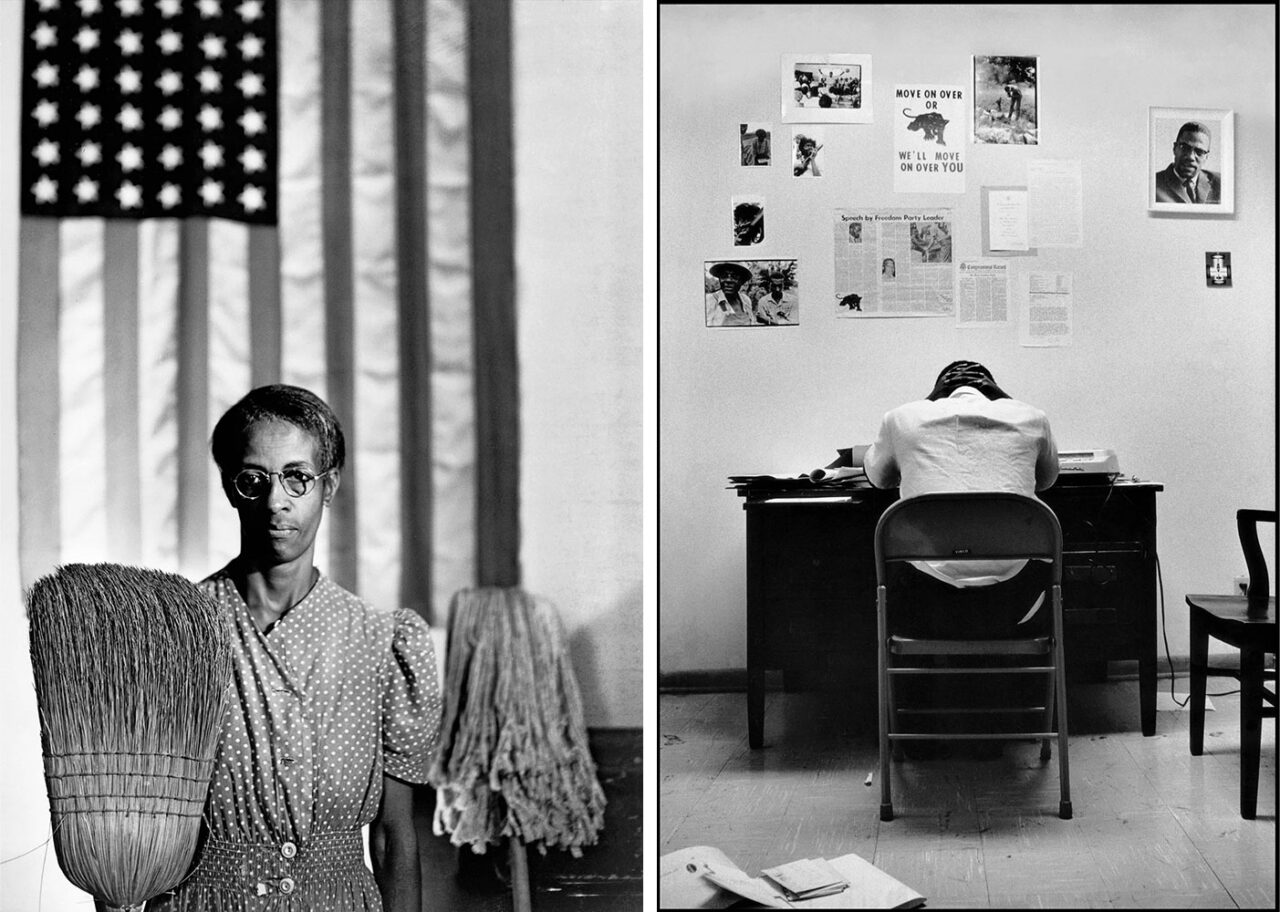

A photographer, filmmaker, composer, and writer, Gordon Parks was one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, describing himself as “an objective reporter with a subjective heart”. This exhibition marks the Pace gallery’s first solo presentation of the artist’s work as part of its ongoing partnership with the Gordon Parks Foundation. Highlights in the show include “American Gothic, Washington D.C.” (1942), an iconic image of Ella Watson, a government employee at the FSA, who poses with a mop and broom against an American flag in the background; “Baptism, Chicago, Illinois” (1953), one of several photographs on view that speak to Parks’s interest in documenting worship and spirituality within Black communities; and a close-up portrait of Ali from 1966. The exhibition also includes selections from Parks’s “Segregation Story”—a series of more than 70 color photographs of Black life in segregated America that he created in 1956, as well as a video installation of his short film “Diary of a Harlem Family” (1967). As he said “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs,” Parks once said. “I knew at that point I had to have a camera.” Born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912, Parks was drawn to photography as a young man when he saw images of migrant workers taken by Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers in a magazine. After buying a camera at a pawnshop, he taught himself how to use it. Despite his lack of professional training, he won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942; this led to a position with the photography section of the FSA in Washington, D.C., and, later, the Office of War Information (OWI). Working for these agencies, which were then chronicling the nation’s social conditions, Parks quickly developed a personal style that would make him among the most celebrated photographers of his era. His extraordinary pictures allowed him to break the color line in professional photography while he created remarkably expressive images that consistently explored the social and economic impact of poverty, racism, and other forms of discrimination. In 1944, Parks left the OWI to work for the Standard Oil Company’s photo documentary project. Around this time, he was also a freelance photographer for “Glamour and Ebony”, which expanded his photographic practice and further developed his distinct style. His 1948 photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader won him widespread acclaim and a position as the first African American staff photographer for “Life”. Parks would remain at the magazine for two decades, covering subjects ranging from racism and poverty to fashion and entertainment, and taking memorable pictures of such figures as Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and Stokely Carmichael. His most famous images, for instance “American Gothic” (1942) and ‘Emerging Man” (1952), capture the essence of his activism and humanitarianism and have become iconic, defining their generation. They also helped rally support for the burgeoning civil rights movement, for which Parks himself was a tireless advocate as well as a documentarian. Parks was a modern-day Renaissance man, whose creative practice extended beyond photography to encompass fiction and nonfiction writing, musical composition, filmmaking, and painting. In 1969 he became the first African American to write and direct a major Hollywood studio feature film, “The Learning Tree”, based on his bestselling semiautobiographical novel. His next film, “Shaft” (1971), was a critical and box-office success, inspiring a number of sequels. Parks published many books, including memoirs, novels, poetry, and volumes on photographic technique. In 1989 he produced, directed, and composed the music for a ballet, “Martin”, dedicated to the late civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Parks spent much of the last three decades of his life evolving his artistic style, and he continued working until his death in 2006. He was recognized with more than fifty honorary doctorates, and among his numerous awards was the National Medal of Arts, which he received in 1988.

Photo Left: Gordon Parks, American Gothic, Washington D.C., 1942, gelatin silver print, 17-3/8″ × 12-1/2″ (44.1 cm × 31.8 cm), image 19-7/8″ × 15-15/16″ (50.5 cm × 40.5 cm), paper 26-1/4″ × 21-1/8″ × 1-1/4″ (66.7 cm × 53.7 cm × 3.2 cm), frame. Courtesy Gordon Parks Foundation and Pace Gallery. Photo Right: Gordon Parks, Stokely Carmichael in SNCC Office, Atlanta, Georgia, 1967, gelatin silver print, 22″ × 15-1/8″ (55.9 cm × 38.4 cm), image 24″ × 20″ (61 cm × 50.8 cm), paper 31″ × 23-1/2″ × 1-1/4″ (78.7 cm × 59.7 cm × 3.2 cm), frame. Courtesy Gordon Parks Foundation and Pace Gallery

Info: Curator: Kimberly Drew, Pace Gallery, 1201 South La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 2/7-30/8/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.pacegallery.com/