TRIBUTE: There Is No There There

In the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, numerous artists from abroad were working in both the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany. Within the framework of grants and bilateral cultural agreements, and alongside migrant workers, exiles, refugees, and ‘foreign workers,’ they came to a divided Germany during the Cold War to continue working on their art and to collabo- rate and exchange with other artists. Some were them- selves migrant workers who only later became artists. Memories of people and landscapes, colors, forms, and visual traditions found their way into their works. Fleeing their native countries and living in exile in their new homeland, political conditions as well as daily work and life became their new pictorial themes.

In the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, numerous artists from abroad were working in both the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany. Within the framework of grants and bilateral cultural agreements, and alongside migrant workers, exiles, refugees, and ‘foreign workers,’ they came to a divided Germany during the Cold War to continue working on their art and to collabo- rate and exchange with other artists. Some were them- selves migrant workers who only later became artists. Memories of people and landscapes, colors, forms, and visual traditions found their way into their works. Fleeing their native countries and living in exile in their new homeland, political conditions as well as daily work and life became their new pictorial themes.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MMK Archive

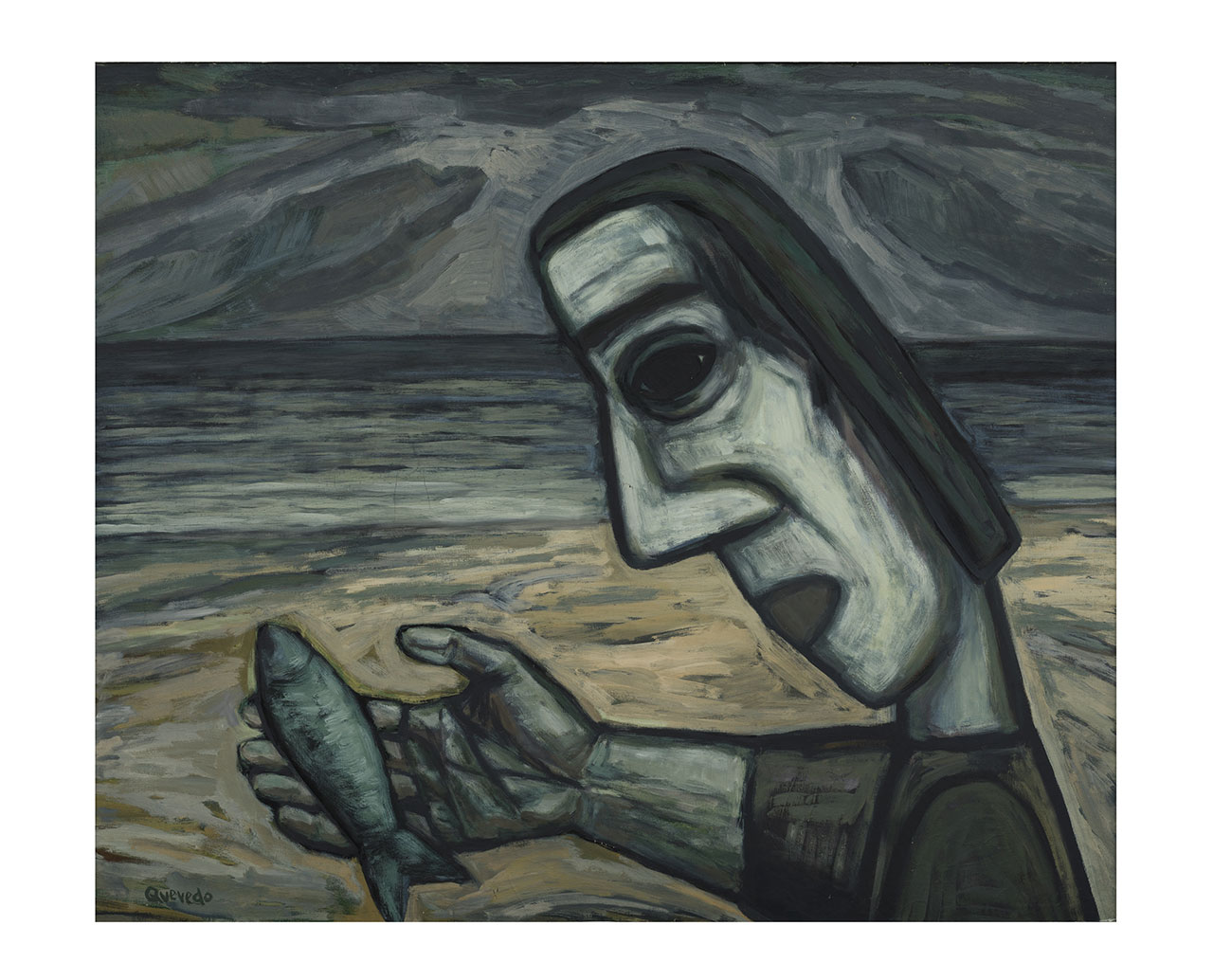

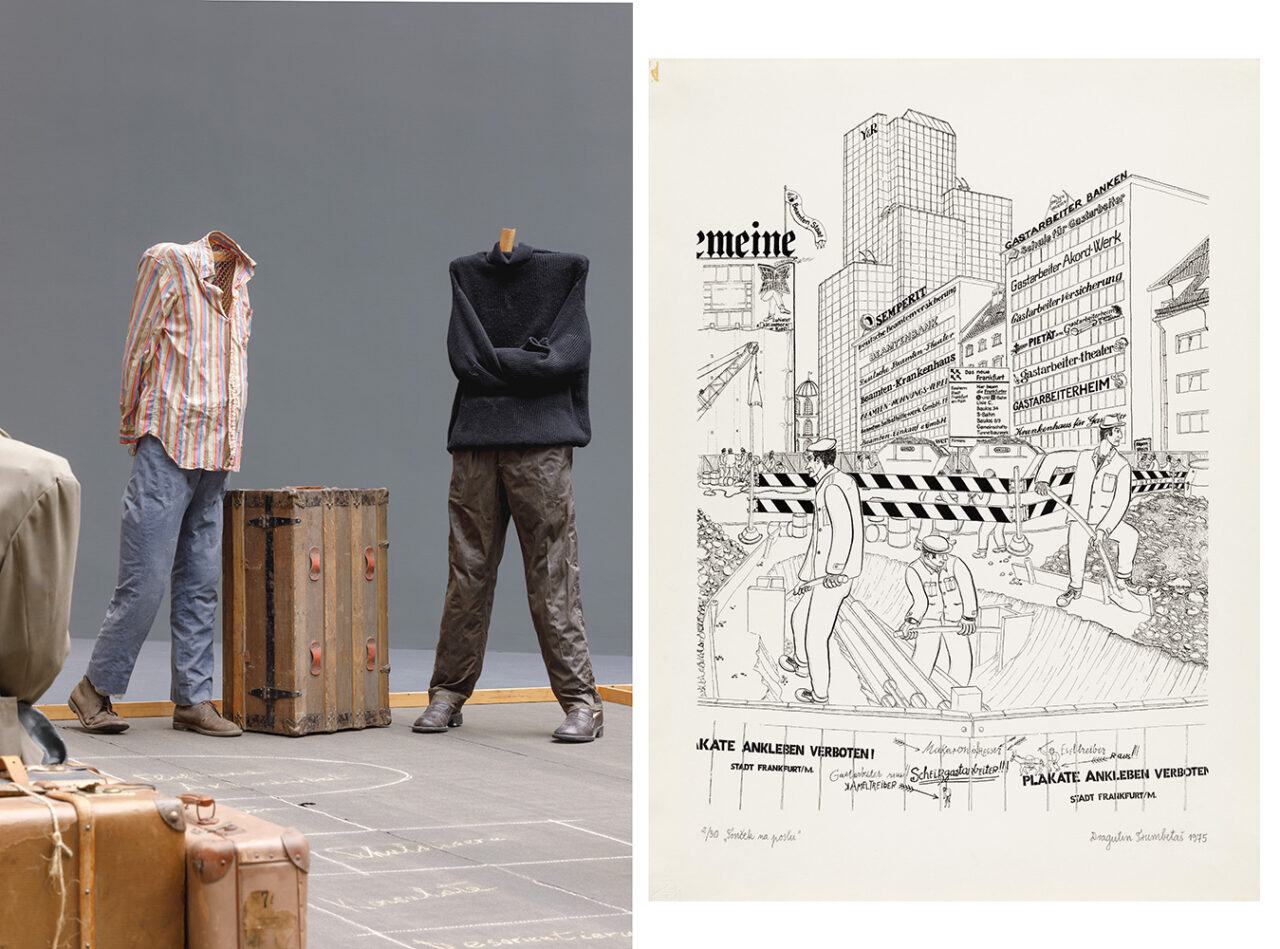

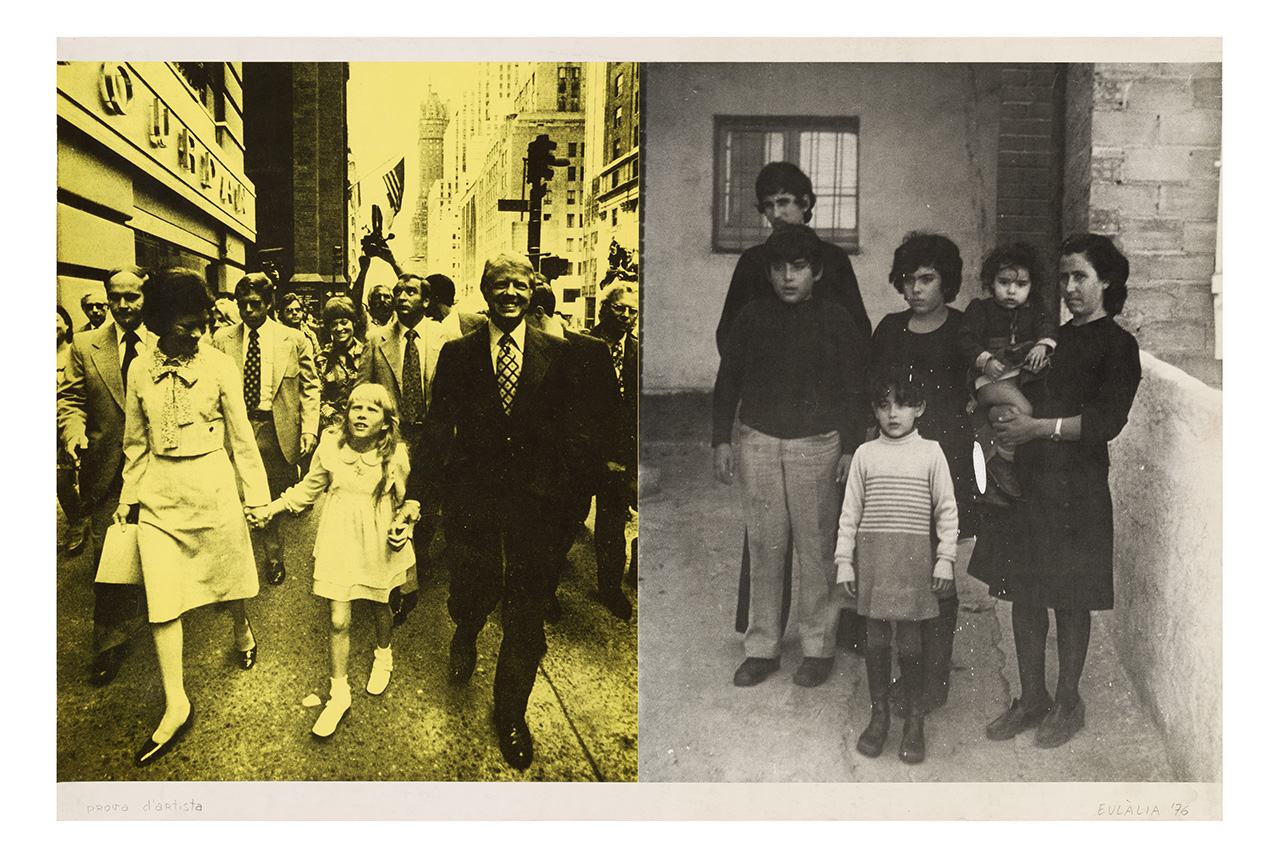

Marginalized within the institutionalized art world due to structural exclusions, the artists nevertheless decisively expanded the discourses on art in both post-National Socialist Germanys. In doing so, they opened up the possibility of seeing different things and, hence, seeing differently. The exhibition “There is no there there” testifies to the richness of their artistic work and the transformative power that works of art can unleash. While what they left behind inevitably changes, the artists directly change the present. Among them Vlassis Caniaris produced works that reflected the realities, dreams, situations, and potential viewpoints of economic migrants who moved to western Europe in search of a better life in the 1960s and ’70s. Even before his scholarship in West Berlin from 1973 to 1975, funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the artist addressed the theme of migration while living in Paris. Caniaris created environments with life-sized dolls that he made himself. He used wire frames, plaster, and glue to form their bodies and clothed them in worn-out fragments of garments held together with pins. The figures are missing human characteristics: some have no hands while the head is absent from others, or some have cans of food forming their shoulders. One example of this kind of environment is the work titled “Hopscotch” (1974). Hopscotch is a traditional outdoor children’s game that requires nothing more than a simple flat surface. The hopscotch court is often marked out on paths or paved surfaces as a sequence of numbered boxes arranged in a particular shape. This hopping game is typically played with a small stone or other such object, which is thrown and marks the space where it lands. Players aim to hop onto all the spaces in the correct order without losing their balance. When a player makes a mistake, their turn passes to the next player. In Vlassis Caniaris’ installation, however, there are words in the spaces rather than numbers, such as “Ausländerpolizei” (Immigration police), “Wohnsituation” (Living situation), “Akkordarbeit” (Piecework), or “Konsulate” (Consulates), which describe the various steps and mechanisms involved in economic migration policy. The artist’s socio-critical environments presenting scenes concerning migration address issues such as exploitation, discrimination, national affiliation, and the removal of fundamental rights in the Federal Republic of Germany. The social and political structures of migration and identity permeate Caniaris’ work, reflecting the desire for dialogue. In 1968, the Greek artist Alexis Akrithakis traveled to West Berlin on a DAAD scholarship, where he eventually spent more than fifteen years of his life. His wife, Fofi Akrithaki, opened the restaurant Estiatórion— known also as Fofi’s—which soon became a meeting place for artists. The image of the suitcase occupies an important place in Akrithakis’ practice. His suitcases often burst into flames, drown in deep waters, or can be found balancing on the edge of a cliff. A recurring motif, they have taken on different forms and repetitions over the years: some carry hidden fragments of barely legible text within them, while others float on the surface of the sea. The use of bent metal or saws symbolizes the poignancy of their story; for example, one of these works is made with metal grids reminiscent of prison bars, behind which are empty beer cans and rusted metal parts. Part of countless migratory lives, the suitcase becomes a metonym for the stories and movements of people forced to flee their home country under constantly changing economic and political conditions. “The Seminars” is a group of works on paper that combine text fragments with photographic imagery. Jannis Psychopedis worked on the Seminars between 1979 and 1981 while staying in West Berlin with a grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Before that, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he remained until 1976. The series depicts a variety of scenes, ranging from newspaper advertisements, anatomical drawings commonly found in medical textbooks, birds, and ancient Greek sculptures, to photo- graphs of workers and headless politicians, representatives of the extreme right-wing military dictatorship of April 21 (1967–74). A large body of handwritten text encloses the images, accompanied by small side notes, smudges, and annotations. Some words are circled to point out their significance, while others are entirely crossed out, making it impossible for the reader/viewer to decipher. Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the text consists largely of a selection of passages from Karl Marx’s seminal work Das Kapital. A striking image of a woman kneeling next to a dead body stands out. The origin of this scene is a photograph taken during the bloody riots that unfolded following the workers’ strike in the city of Thessaloniki in May 1936. Tasos Tousis, a twenty-five-year- old driver from the nearby city of Asvestochori, was the first victim shot by police forces. Ever since, the photograph of the mourning mother beside her dead son’s body has become an important political document in the histories of workers’ rights in Greece while serving as a symbol for the political instability that would in the same year lead to the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas (1936–41). In the large- format print “Migrants” (1978), people stand patiently in line. A Greek sculpture hangs above them. The artist gives space to the stories of the numerous people who have sought better living and working conditions abroad since the late 1960s. Jannis Psychopedis removes images, events, and texts from their original context, opening them up to new associations and critical reflections.

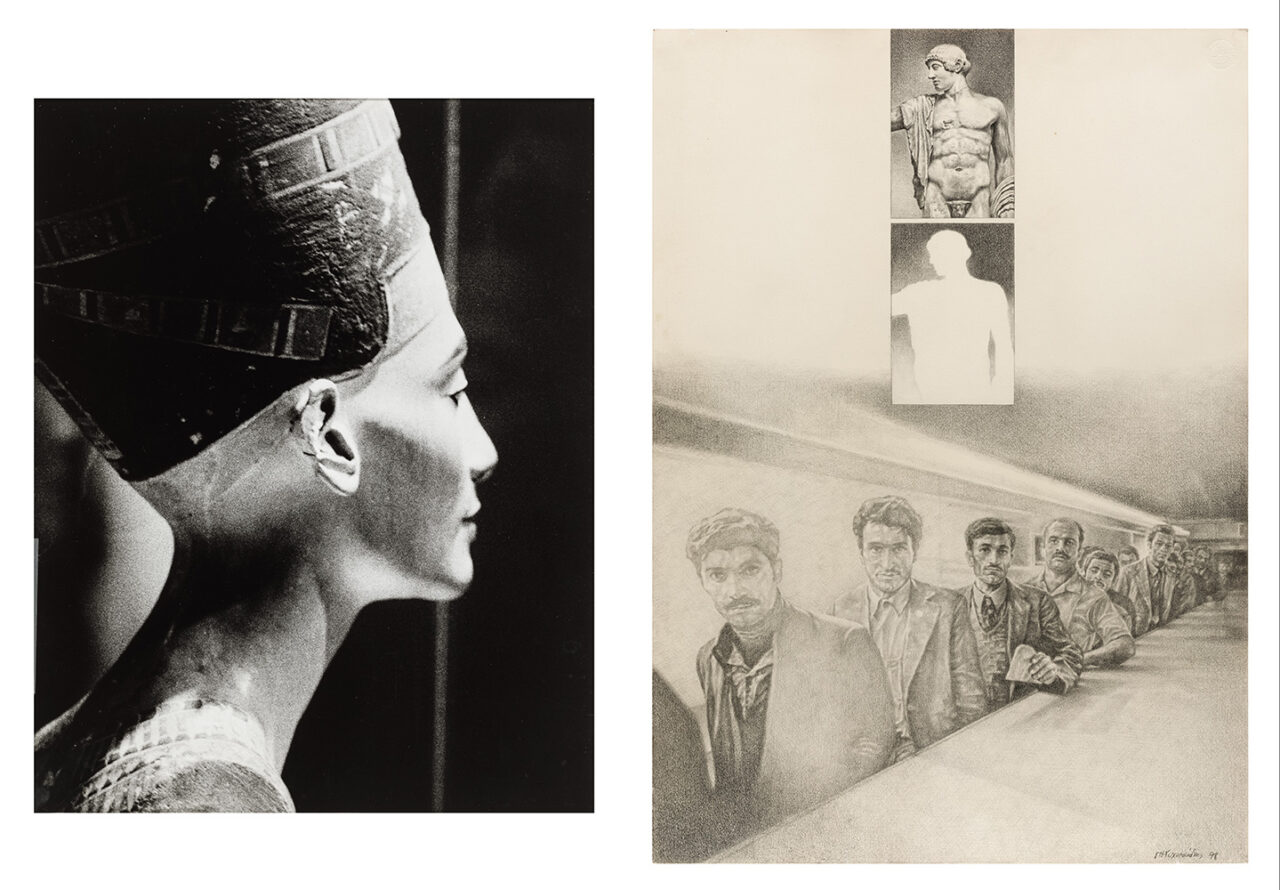

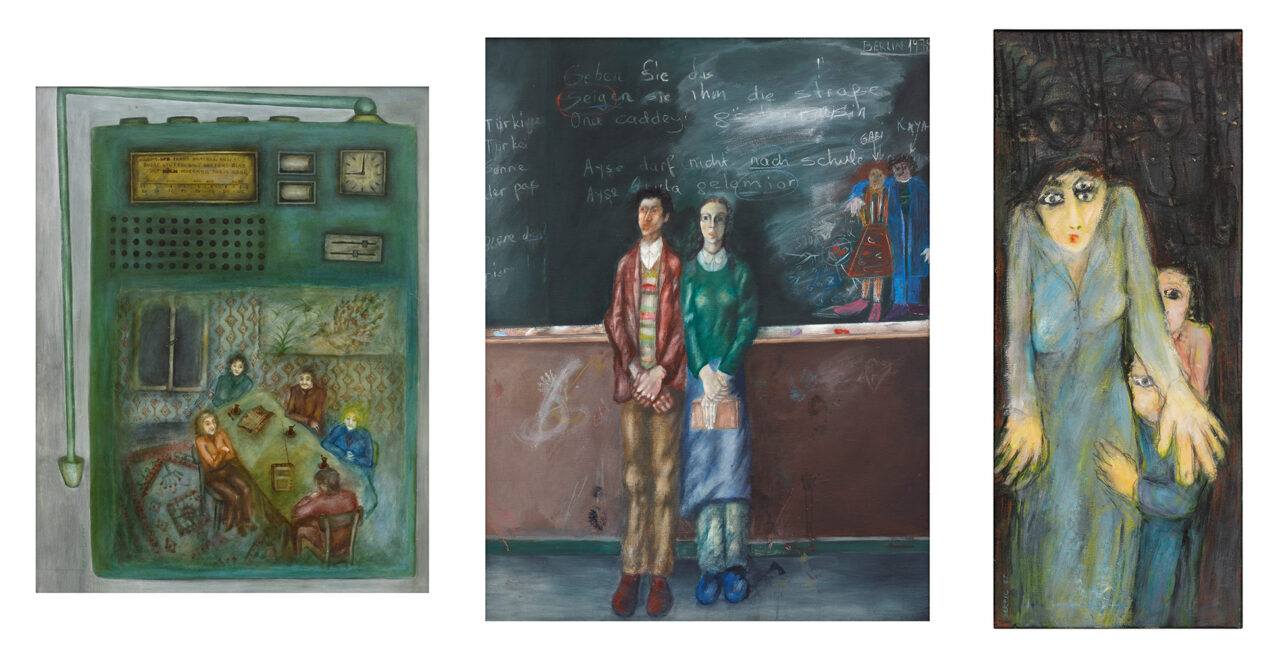

When the artist Serpil Yeter came to West Berlin in 1980, she was one of only a few artists from Turkey. She describes migrating to the Federal Republic of Germany as a turning point in her life. Yeter painted whatever she observed in her surroundings: lonely Berlin women with their dogs, blue-collar workers riding the subway after work, and punks. Her painting “Es ist 9 Uhr!” (It’s 9 O’Clock, 1981) depicts an everyday scene: a radio covers the entire surface, its aerial extended in a right angle around the edge of the painting. In the middle of this enormous radio, where the speakers are usually found, there is a group of people assembled to listen to the radio program—a situation that migrants would be very familiar with. Public broadcasters in the FRG initiated foreign-language radio broadcasts at the time, primarily to familiarize mi- grant workers with the conditions in the Federal Republic and to counteract political influences from outside during the Cold War—also in the interests of the sending countries. This was intended to minimize the impact of the so-called ‘Eastern broadcasts,’ which could also be received in the FRG; Radio Budapest, for example, broadcast radio pro- grams for the Turkish-speaking population. In November 1964, a radio program was launched that quickly became one of the most important Turkish-language sources of information for migrant workers living in the FRG—at least until the introduction of satellite television. “Köln Radyosu” (Radio Cologne) became a crowd puller, attracting a large proportion of Turkish-speaking people to the radio every evening. Migrants from Turkey used this radio program to find out about news from their home country, as well as from the FRG and around the world in their native language. In addition to the news, music and comedy provided the entertainment they so longed for. “Köln Radyosu” also offered social counseling and guidance. The broadcasters received countless letters and calls from people hoping for answers to their everyday prob-lems, such as difficulties at work or family reunification. The program was geared towards the needs of its listeners and became a witness to an era of migration for decades— it was closely interwoven with its challenges, moods and discourses. Sohrab Shahid Saless in the movie “In der Fremde / Dar Ghorbat” (Far From Home, 1975) depicts the monotonous life of the factory worker Husseyin in Kreuzberg, a district in what was then West Berlin. His life is played out doing piecework at a punch- ing machine in an industrial manufacturing facility, in the subway, in the streets of Berlin, whose building façades still bear the scars of war, and with the other people shar- ing his apartment: a family, other male migrant workers, and a student. Various circumstances have brought them all from Turkey to the Federal Republic of Germany. In this social critique, the director Sohrab Shahid Saless employs long, unhurried takes that allow the viewer to observe the quiet and open-minded protagonist Husseyin as he searches for familiarity and social warmth in a setting that is foreign, dreary, forbidding, and some- times racist. Following the 1973 military coup led by Augusto Pinochet and a short period of imprisonment, César Olhagaray was forced to leave his home country, Chile, and flee to Europe. After a short stay in France, he arrived in the GDR, where he began his studies in painting and graphic arts in Dresden at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. In the late 1980s, he continued his studies at the Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin. Several solidarity measures were enacted by the GDR shortly after Pinochet came to power, including the acceptance of numerous refugees who were targeted and persecuted by the dictatorship. Human bodies, mythical creatures, and fantastical beings are often tethered to each other in Olhagaray’s work. They swim down a yellow river, rush along a purple street, lie under an orange sun, or dance under the pink moon- light. However, his fictional stories have a strong political undertone. These fantastical scenes become a sharp commentary in which Olhagaray addresses his own experiences of imprisonment while remaining rooted in the collective. Over the years, the artist has created an extensive body of work consisting of large murals in public spaces, such as on the façade of an East Berlin club in the 1980s or on the occasion of the National Festival of Mozambican Youth in Maputo to commemorate Mozambique’s independence from Portugal in 1975. Both, like numerous other public murals in Dresden, London, or Paris, are clear signs of opposing war and racism. None of these works exist today. In Grazia Eminente’s work, a huge photograph of an airplane is affixed to the window of Reisebüro Imperial, a travel agency in Kreuzberg, with the words “Aktarmasız Direkt Berlin Istanbul Berlin” written underneath. A woman stands in a shop surrounded by numerous price tags, her face framed by a headscarf, and her eyes lowered. “Sucukları” is written in capital letters on a sign on the wall, while the counter is fully stocked with meat products. Her incredibly beautiful profile, her high cheekbones, and her sensual mouth are all hallmarks of the reception of the Egyptian Queen Nefertiti. The photo graphs by Italian artist Grazia Eminente show how differently aspects that are foreign and unknown are received. While one woman is revered in the museum, the other is ignored in everyday life. Eminente left Spain in 1974 after her husband, the painter and set designer Eduardo Arroyo, was imprisoned, lost his Spanish citizenship, and was recognized as a political refugee in France. Grazia Eminente taught herself photography and film processing while staying in West Berlin from 1975 to 1976.

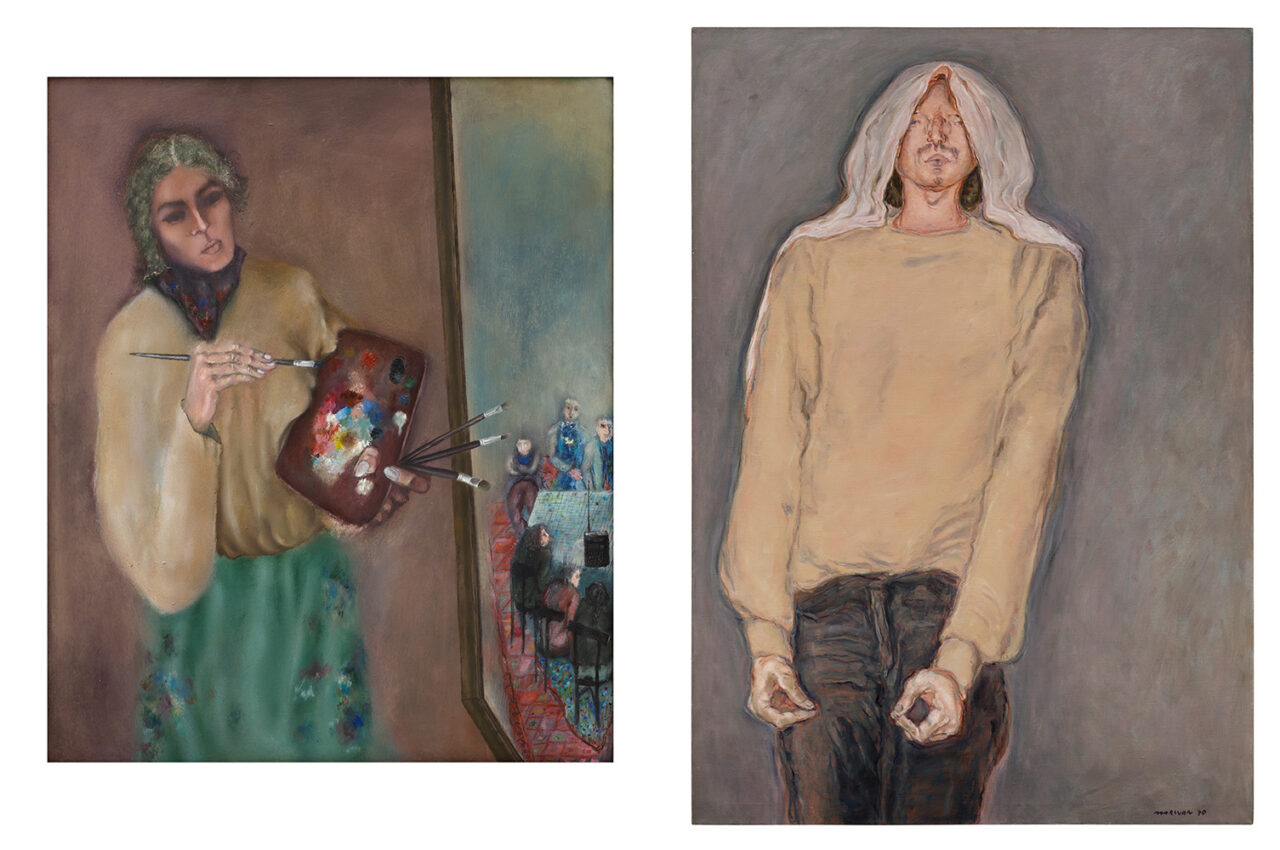

Works by: Abed Abdi, Alexis Akrithakis, Gülden Artun, Akbar Behkalam, Cecilia Boisier, Vlassis Caniaris, Rimer Cardillo, Teresa Casanueva, Ali Rıza Ceylan, Santos Chávez, Guillermo Deisler, Grazia Eminente, Eulàlia Grau, Getachew Yossef Hagoss, Azade Köker, MARWAN, César Olhagaray, Jannis Psychopedis, Núria Quevedo, Sohrab Shahid Saless, Manuela Sambo, Navina Sundaram, Dito Tembe, Rıza Topal, Drago Trumbetaš, Chetna Vora, Hanefi Yeter, Serpil Yeter, Hamid Zénati and Želimir Žilnik

Photo: Vlassis Caniaris, Sliced Cucumber, 1974, Vlassis Caniaris Estate & Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zürich/Paris, photo: Axel Schneider

Info: Curators: Gürsoy Doğtaş and Susanne Pfeffer, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Domstraße 10, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Duration: 13/4-29/9/2024, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 11:00-18:00, Wed 11:00-20:00, www.mmk.art/

Right: Drago Trumbetaš, Tonček na poslu (Tontschek bei der Arbeit), Grafikmappe Gastarbeiter, 1975, © Privatbesitz der Familie Trumbetaš, photo: Axel Schneider

Right: Jannis Psychopedis, Migrants, 1978, Private collection (GR), photo: Axel Schneider

Right: MARWAN, Untitled, 1970, © Estate MARWAN / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024, photo: Axel Schneider

Right: Rıza Topal, Untitled, 1964, courtesy the artist, photo: Axel Schneider

Center: Hanefi Yeter, Analphabeten in zwei Sprachen, 1987, Kunstraum Kreuzberg /Bethanien (DE), photo: Axel Schneide

Right: Serpil Yeter, Überall das Gleiche, 1985, courtesy the artist, photo: Axel Schneider