PRESENTATION: Josef and Anni Albers Iconic Couple Of Modernism, Part II

Josef and Anni Albers were pioneering 20th-century artists whose work, writing, and teaching demonstrably transformed the way that people see color and the processes of making art. The Boghossian Foundation presents “Josef and Anni Albers Iconic couple of modernism”, the first exhibition in Belgium of the work of Josef and Anni Albers, two pioneers of modernism who produced pivotal artworks that marked the history of 20th century art (Part I).

Josef and Anni Albers were pioneering 20th-century artists whose work, writing, and teaching demonstrably transformed the way that people see color and the processes of making art. The Boghossian Foundation presents “Josef and Anni Albers Iconic couple of modernism”, the first exhibition in Belgium of the work of Josef and Anni Albers, two pioneers of modernism who produced pivotal artworks that marked the history of 20th century art (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Boghossian Foundation Archive

Featuring some 100 artworks (paintings, assemblages, photographs, graphic works, textiles, films, and furniture) the exhibition “Josef and Anni Albers Iconic couple of modernism” retraces the Alberses’ respective artistic careers and sheds light on their close and intimate relationship that allowed them to mutually enrich and empower one another throughout their lives. Many of the artworks featured in the exhibition were donated by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation to the Musées d’Art moderne de Paris in 2022. The exhibition unfolds in the Villa Empain. Initially designed for a couple, the pure lines of this masterpiece of Art Deco architecture heralded the arrival of Modernism. The Villa Empain provides the perfect setting to showcase the Alberses thoroughly modern, international vision, and, more specifically, the aesthetic and pedagogical values they still embody to this day. The show also endeavours to examine the legacy of Josef and Anni Albers and the influence of their work and teachings. Olivier Gourvil is an abstract painter, or should we say an almost abstract painter, he combines a double reference to images of the real world and reproductions of signs of universal value, and thus makes singular plastic figures emerge. Guided by what she calls her “inner choreography” Linda Karshan makes spare, monochromatic, abstract prints and drawings that serve as direct reflections of the process of their making. Though she began her career producing expressive compositions, in 1994 she developed a performance-based method for making work, in which every mark is associated with her rhythmic and regulated breathing, her counter-clockwise turning of the paper, the motion of her entire body, and the musical way in which she counts off increments of time. Mehdi Moutashar’s art lies at the confluence of two artistic traditions, the western heritage of geometric abstraction and the Islamic aesthetic tradition of geometrical order and lines. His art is a radical, geometrical abstraction with figures that are never enclosed inside the limits of a contour but open, fragmentary and constantly shifting. With his drawings and collage paintings, Vico Persson aims to mix formal minimalism with imaginative openness, and explore the relationships of controlled structure and open-ended randomness. The artist thinks of it like a ballet: simple and disciplined at first glance with underlying layers of complexity discovered after a closer look. With patience, meticulousness and sobriety, Leïla Pile takes turns walking, measuring, drawing, dyeing, weaving, unwinding, wrapping, systematically observing a precise and rigorous working protocol that allows her to grasp spaces and magnify the material. Each new spatial context is a ground for inspiration and experimentation, both the origin and the purpose of the artist’s gesture. Charlotte von Poehl’s work has a recurrent focus on repetition and seriality. Using ordinary materials and techniques, von Poehl draws repetitive patterns and makes miniature modeling clay sculptures, which form large floor installations, expanding according to the size of the exhibition space. For von Poehl, writing down notes, citations and making drawings is made into a daily routine that holds a central role in her artistic approach.

Each of her works can be seen as a fragment of this larger ongoing project, simply torn out of the continuous process. Damien Poulain is an artist responding to various invitations, engaging with design, architecture, and the built and natural environments. His practice transmutes influences from Shintoist, primitive, and heraldic symbology, as well as contemporary material and digital culture, to propose a universal visual language. Through an evolving range of formats including textile, paint, sculpture, and ephemeral architectural volumes, he devises glyphic systems of geometry and color. These codes raise questions about the ways humans relate to each other, to their surroundings, and to the mystery of existence. A graduate of the Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2021 and of the Arts Décoratifs in Printed Image, Chloé Vanderstraeten seeks to create poetic time-spaces through drawing, in dialogue with iconographic sources stemming from architectural sketches, choreographic notation, and a prehistory of handwritten gesture. Her practice raises the question of the use of the body: what happens when we use our body to sleep, to breathe, to walk? Bernard Villers developed his pictorial research and became a leading figure of the Belgian art scene. His practice questions the traditional relationship between support and color, revealing a true symbiotic interaction and fostering an equal dialogue between those two essential elements. The artist diverts the viewer’s expectations by proposing chromatic interventions that are direct and minimal without being devoid of emotion: the beauty of everyday life reveals itself in the subtle imperfections of Bernard Villers’ lines.

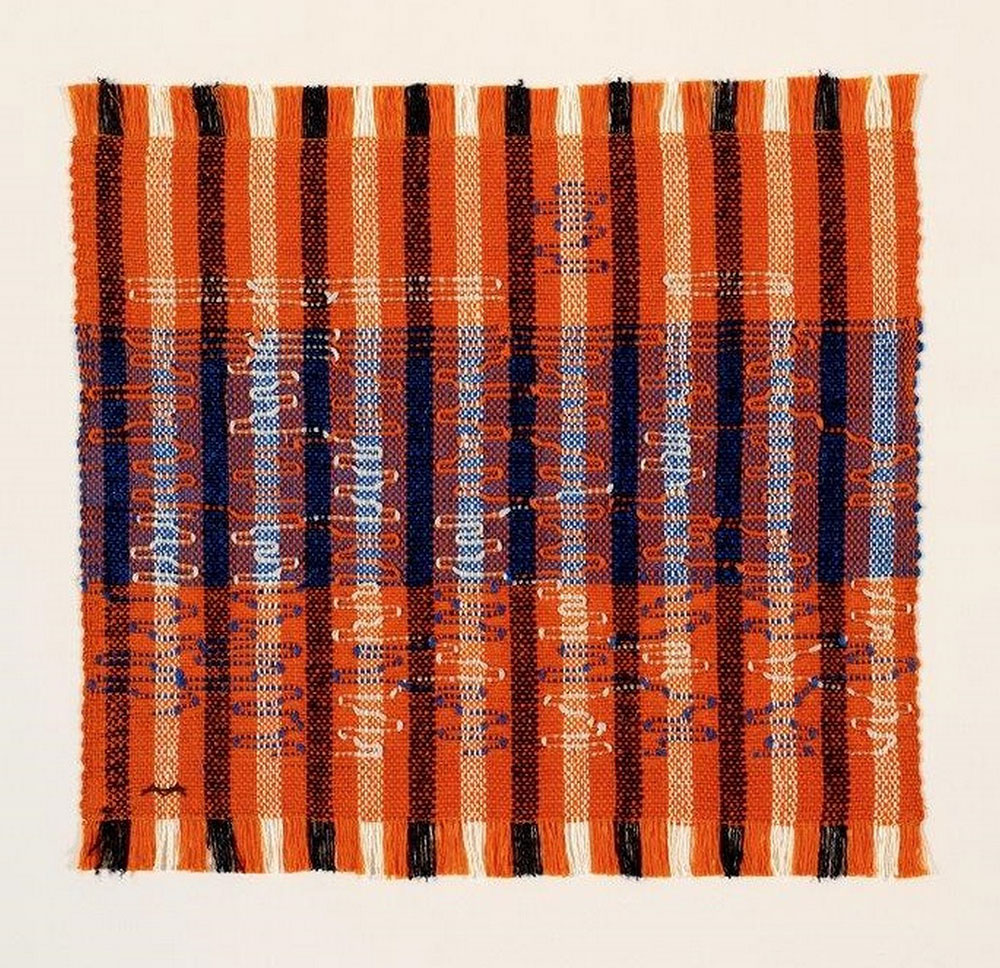

Although Anni and Josef Albers worked with different materials, the exhibition show how much they influenced each other, sharing the same sense of color, rhythm and form that reflects the principles of the Bauhaus – such as respect for the material and for experimentation. The impact of the work and teaching of the Albers on the development of modern art cannot be overstated. Josef and Anni Albers, met in Weimar, Germany in 1922 at the Bauhaus. This new teaching institution, which transformed modern design, had been founded three years earlier, and emphasized the connection between artists, architects, and craftspeople. Before enrolling as a student at the Bauhaus in 1920, Josef had been a school teacher in and near his hometown of Bottrop, in the northwestern industrial Ruhr region of Germany. Initially he taught a general elementary school course; then, following studies in Berlin, he gave art instruction. At the same time, he developed as a figurative artist and printmaker. Once he was at the Bauhaus, he started to make glass assemblages from detritus he found at the Weimar town dump and from stained glass; he then made sandblasted glass constructions and designed large stained-glass windows for houses and buildings. He also designed furniture, household objects, and an alphabet. In 1925, he was the first Bauhaus student to be asked to join the faculty and become a master. At the end of the decade he made exceptional photographs and photo-collages, documenting Bauhaus life with flair. By 1933, when pressure from the Nazis forced the school to shut its doors, Josef Albers had become one of its best-known artists and teachers, and was among those who decided to close the school rather than comply with the Third Reich and reopen adhering to its rules and regulations. Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann went to the Bauhaus as a young student in 1922. Throughout her childhood in Berlin, she had been fascinated by the visual world, and her parents had encouraged her to study drawing and painting. Having been brought up in an affluent household where she was expected simply to continue living the sort of comfortable domestic life enjoyed by her mother, she rebelled by deciding to be an artist and going off to an art school that embraced modernism and where the living conditions were rugged and the challenges immense. She entered the weaving workshop because it was the only one open to her, but soon embraced the possibilities of textiles. She and Josef, eleven years apart in age, met shortly after her arrival in Weimar. They were married in Berlin in 1925—and Annelise Fleischmann became Anni Albers. At the Bauhaus, Anni experimented with new materials for weaving and became a bold abstract artist. She used straight lines and solid colors to make works on paper and wall hangings devoid of representation. In her functional textiles she experimented with metallic thread and horsehair as well as traditional yarns, and utilized the raw materials and components of structure as the source of design and beauty. In 1925 the Bauhaus moved to the city of Dessau to a streamlined and revolutionary building designed by Walter Gropius, the architect who had founded the school. The Alberses, who had become friends with Paul and Lily Klee, Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, Oscar and Tut Schlemmer and Lyonel and Julia Feininger, eventually moved into one of the masters’ houses designed by Gropius. After the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close in 1933, the architect Philip Johnson, then a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Josef and Anni Albers were invited to the USA when Josef was asked to make the visual arts the center of the curriculum at the newly established Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Black Mountain College was a liberal arts college with an innovative and progressive curriculum that repositioned the study and practice of art from the margin to the center of the undergraduate program, and Albers’s preliminary art course in materials and form was one of only two courses required of all students, regardless of major. Although Black Mountain’s focus was not the training of professional artists, the emphasis placed on the centrality of art to everyday life, and its integrative and collaborative approach to art-making, attracted creative students and faculty in every media, from painting and literature to dance and architecture. Albers brought the theories and teaching methods of the Bauhaus to Black Mountain, but he was influenced in turn by the progressive educational philosophy of American philosopher John Dewey, with its emphasis on experimentation and direct experience as central to the learning experience. They remained at Black Mountain until 1949, while Josef continued his exploration of a range of printmaking techniques, took off as an abstract painter, made collages of autumn leaves, kept writing, became an ever more influential teacher and wrote about art and education. Anni made extraordinary weavings, developed new textiles, and taught, while also writing essays on design that reflected her independent and passionate vision. Meanwhile, the Alberses began making frequent trips to Mexico, a country that captivated their imagination and had a strong effect on both of their art. They often said that, “In Mexico, art is everywhere”: this was their ideal for human life. In 1950, the Alberses moved to Connecticut. From 1950 to 1958, Josef Albers was chairman of the Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art. There, and as guest teacher at art schools throughout North and South America and in Europe.

Artists: Anni Albers and Josef Albers, Olivier Gourvil, Linda Karshan, Mehdi Moutashar, Vico Persson, Leïla Pile, Charlotte von Poehl, Damien Poulain, Chloé Vanderstraeten and Bernard Villers.

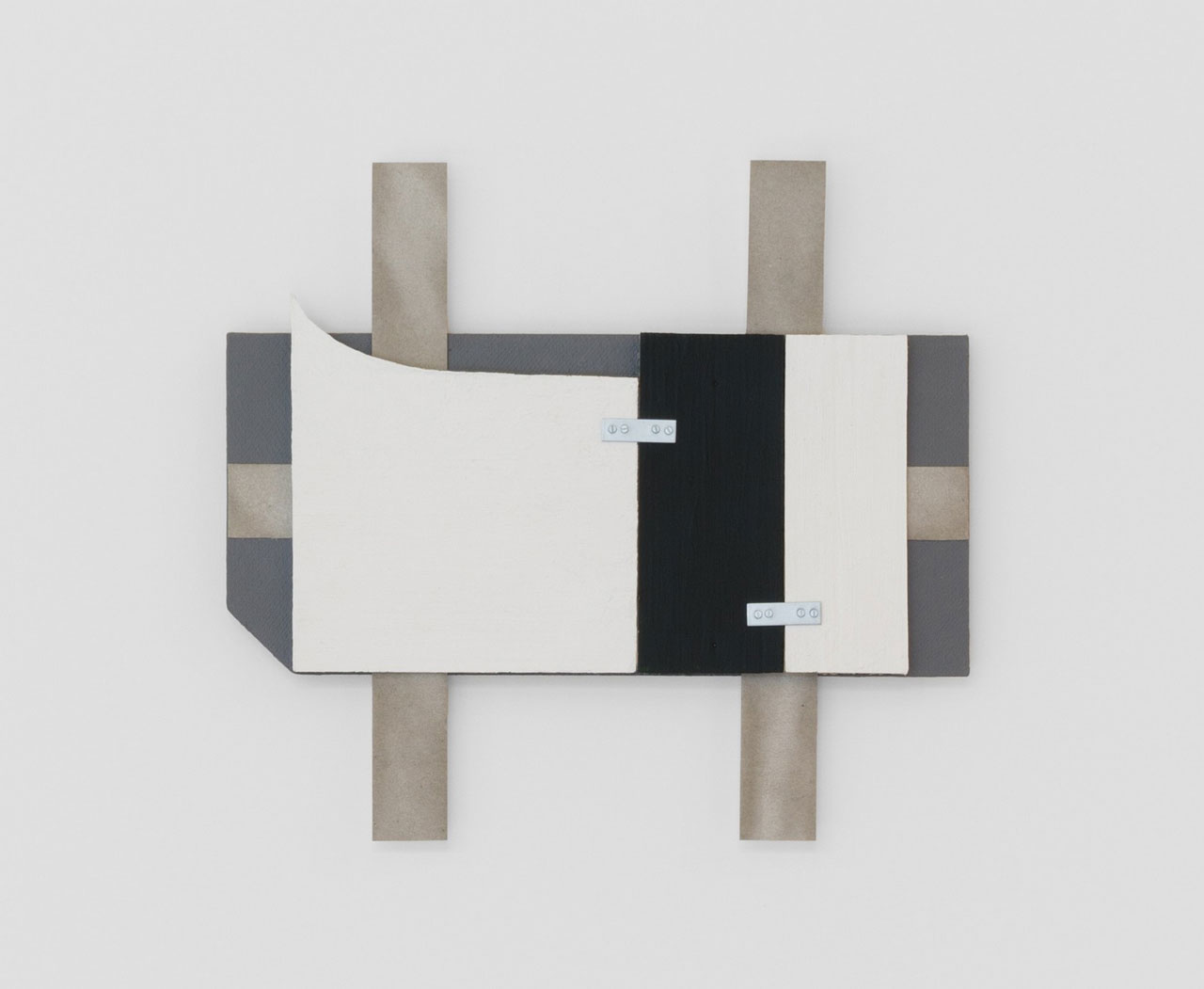

Photo: Chloé Vanderstraeten, La mue, 2022, Colored pencil and folding on paper, metal structure, © Silvia Cappellari

Info: Curators: Edouard Detaille and Julia Garimorth, Bogosian Foundation, Villa Empain, Centre for art and dialogue between Eastern and Western cultures Avenue Franklin Roosevelt, 67, Brussels, Belgium, Duration: 10/4-8/9/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, https://villaempain.com/

Right: Anni Albers, W/Co , 1974, Silkscreen, offset printing, © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Right: Mehdi Moutashar, Un et demi (detail), Collage, silkscreen, pencil (6 boards), © Silvia Cappellari