PRESENTATION: Casablanca Art School-A Postcolonial Avant-Garde 1962–198

Just a few years after Morocco gained independence in 1956, Casablanca became a vibrant center of cultural renewal. The exhibition “Casablanca Art School A Postcolonial Avant-Garde 1962–1987” presents the unique and influential work of the Casablanca Art School in a first major, long-overdue exhibition. The main representatives of this innovative school (Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, Bert Flint, Toni Maraini and Mohamed Melehi) together with students, teachers, and associated artists—quickly became the central driving force for the development of postcolonial modern art in the region.

Just a few years after Morocco gained independence in 1956, Casablanca became a vibrant center of cultural renewal. The exhibition “Casablanca Art School A Postcolonial Avant-Garde 1962–1987” presents the unique and influential work of the Casablanca Art School in a first major, long-overdue exhibition. The main representatives of this innovative school (Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, Bert Flint, Toni Maraini and Mohamed Melehi) together with students, teachers, and associated artists—quickly became the central driving force for the development of postcolonial modern art in the region.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt Archive

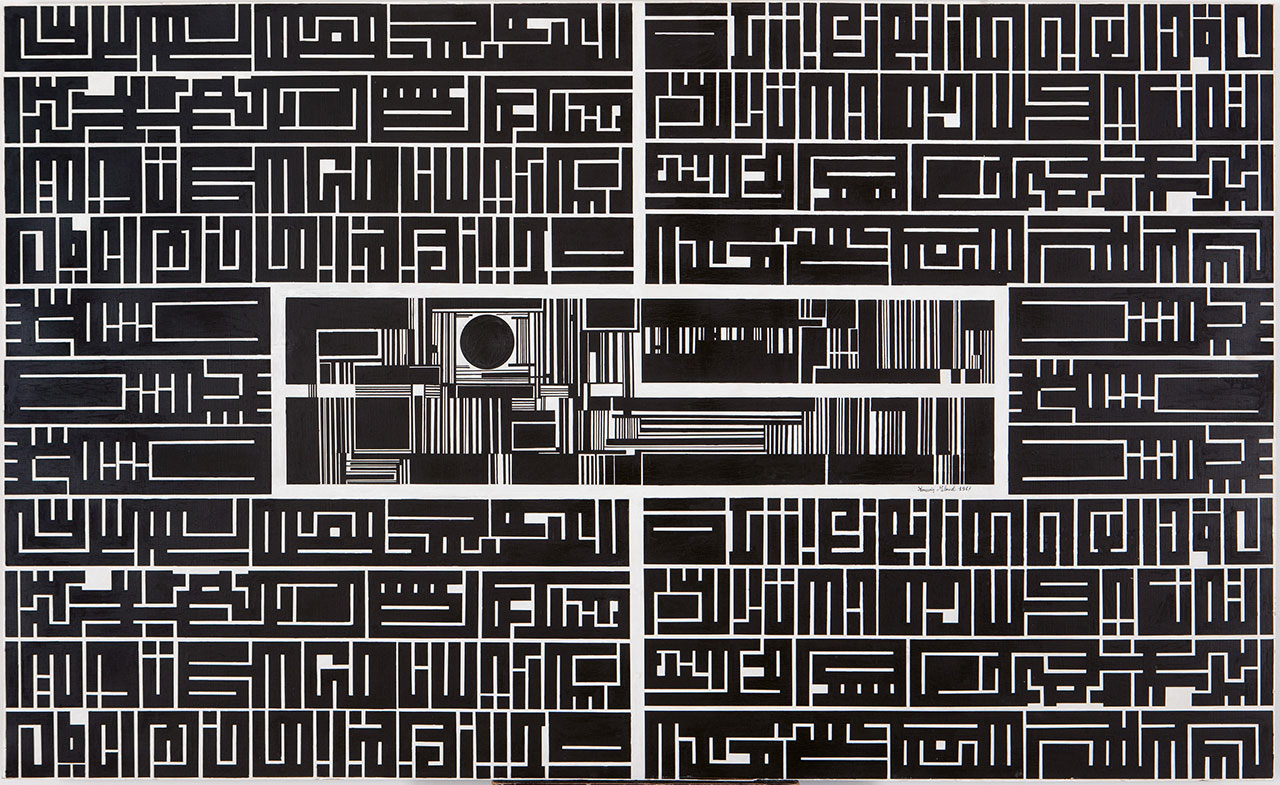

Engaging with the ideas of the Bauhaus movement, they reevaluated the connection between the arts, crafts, design, and architecture in the local context, fusing Western metropolitan arts with elements of the vernacular heritage that had been undermined during the colonial era. The exhibition “Casablanca Art School A Postcolonial Avant-Garde 1962–1987” presents some 100 works by 22 artists, including dynamic abstract paintings and urban murals, crafts, graphic design, interior design, and typography. Rarely seen archive material, such as film footage, vintage journals, photographs, and prints, complements these displays, revealing a transnational Moroccan art scene. Founded in 1919 during the French protectorate, École Municipale des Beaux-Arts de Casablanca (later renamed the Casablanca Art School) followed Western pedagogical approaches, disregarding the region’s traditional arts and crafts and admitting students on the basis of ethnicity, gender, and social class. Morocco gained its independence in 1956, and in 1962, Casablanca Art School appointed the young artist Farid Belkahia as its director, a position he held until 1974. During his tenure, Belkahia opened the school’s doors to Moroccan and female students and appointed like-minded teachers who helped him to reimagine Moroccan visual arts and education. This room introduces the many intersecting paths paved by figures such as Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and Mohamed Melehi, who formed the school’s core; Toni Maraini, who articulated the group’s shared vision through manifestos and essays; and André Elbaz, who, at Belkahia’s behest, taught for one academic year. Maurice Arama was the Casablanca Art School’s first Moroccan director from 1960 to 1962. He played an important role in the renovation of the school’s building and studios, giving the curriculum a new direction, introducing art history studies as well as courses in ceramics, graphic arts, and advertising—innovations further developed by his successor, Farid Belkahia. Perhaps Arama’s most important innovation was to inaugurate Morocco’s first grassroots “museum of modern art” within the school, which was open to the public. It formed part of the school’s estate and curriculum, hosting both student exhibitions and international events. Before becoming director of the Casablanca Art School in 1962, Farid Belkahia had spent two years in Prague. There, he sympathized with global anticolonial movements. His painting Sévices (1961–62) refers to the violence of the French army during the war in Algeria. In “Cuba Sí” (1961), Belkahia responds to the Bay of Pigs invasion, organized by the USA against the Cuban revolutionary government under Fidel Castro. The artist André Elbaz was the first tutor Belkahia recruited while he was director of the Casablanca Art School. They had met at the first Paris Biennale in 1959 and shared an eagerness to return to Morocco to establish an innovative institution for the study of art. Elbaz, appointed professor of painting, experimented with collage during his first (and only) year at the school. The mixed-media works shown here were exhibited at the Zwemmer Gallery in London in 1963. The Casablanca Art School’s first landmark exhibition was held in 1966 in the foyer of the Théâtre National Mohammed V in Rabat. Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and Mohamed Melehi became known as the “Casablanca Trio” or “Casablanca Group” following this event. The presentation of their work in this semi-public space stood in complete contrast to the state-organized salon exhibitions that undermined Moroccan artists’ work. A week before the exhibition opened, Chabâa published an important manifesto-like article in Arabic in the newspaper Al-Alam on the concept of painting and the plastic language, as well as the way in which Morocco’s “abstract” plastic traditions challenge colonial standards and norms. The two open-air “Présence Plastique” exhibitions presented by the Casablanca Art School in 1969 made a bold statement: modern art would now be part of Moroccan everyday life. By this time, three additional artists had joined the school as professors: Mohamed Ataallah, Mustapha Hafid, and Mohamed Hamidi. But more than ten years after independence, Moroccan artists still found it difficult to find spaces or galleries to exhibit their work. In a bid for visibility, six Casablanca Art School artist-professors united to develop the manifesto exhibition series “Présence Plastique”. “Présence Plastique” was staged in protest against the state-organized Salon du printemps (Spring Fair), a colonial relic that considered Moroccan artists’ work “naïve.” Casablanca Art School artists brought their artwork to the streets. They installed paintings in two public squares in May 1969: Jemaa el-Fna, Marrakech, and a few weeks later, Place du 16 Novembre, Casablanca. This nomadic exhibition also traveled to two high schools in Casablanca in 1971, reaching a next-generation audience. It became a defining moment for Moroccan art history.

The 1968 annual Casablanca Art School exhibition launched Moroccan “new wave” art. In collaboration with their teachers, some of the school’s most pioneering students, such as Malika Agueznay, Abdellah El Hariri, and Houssein Miloudi, produced and displayed works at the city’s Parc de la Ligue Arabe La Coupole gallery. In his first years as the school’s director, Farid Belkahia invited Toni Maraini to establish the first modern art history course in Morocco. Bert Flint taught visual anthropology, and the school appointed two new tutors: Mohamed Melehi to teach painting, collage, and photography, and Mohammed Chabâa as a tutor in graphic design and interior design. These new departments merged ideas from art, craft, design, and architecture, influenced by their staff’s studies abroad and the interdisciplinary approach of the Bauhaus movement. Working alongside their students, the teaching staff began to dismantle the Western styles and methods previously taught at the school, such as easel painting. They encouraged students to research African and Amazigh heritage and led study trips focused on archaeology, pottery, calligraphy, and religious paintings, as well as techniques of weaving, leatherwork, jewelry, and tattoos. Collectively, by the 1968 exhibition, their artwork demonstrated a synthesis of Afro-Amazigh influences in a modernist language and style. Ahmed Cherkaoui was a pioneering, internationally renowned representative of modern Moroccan art who paved the way for rethinking the relationship between artists and artisans. Although he was not a lecturer at the Casablanca Art School, he remained an artistic friend and mentor, exhibiting alongside the school’s artists. Mohamed Melehi photographed Cherkaoui’s drawings, shown here, to illustrate both artists’ fascination with the patterns found in Amazigh talismans and tattoos. According to Casablanca Art School tutor Mohammed Chabâa, “the poster is a painting that is accessible to all.” Casablanca Art School artists used graphic design to bring art into the public sphere, enhancing traditional mediums like painting in their workshops with new approaches and strategies borrowed from other fields. Tutor Mohamed Melehi, for example, combined painting with collage and opened a photographic studio, while Chabâa taught the decorative arts, scenography, and neo-calligraphy. Melehi and Chabâa co-designed the journal Souffles, as they did many of the posters and books displayed here. Melehi described Souffles as a “thought-provoking blend of poetry, literature, and cultural critique,” which aspired to decolonize and democratize Moroccan arts and culture. During Morocco’s decolonization period, parallel historical developments motivated solidarity with other countries and movements. The posters on this wall, where art merges with cultural and political activism, feature calls for the support of the people in Chile who rose up against the Allende regime, the people caught up in the violence of the Angolan Civil War, and solidarity with the Palestinian people. Some of the posters contain depictions of violence and militarized combat. Herbert Bayer and Mohamed Melehi met in 1968 at the International Sculpture Symposium in Mexico City. A major figure at the Bauhaus School in both Weimar and Dessau, Germany, Bayer had taught composition, advertising, and typography—all fields that Melehi was very interested in. From 1963 on, Bayer traveled to Morocco regularly. His 1970s lithographs, in particular, show the influence of these visits. Bert Flint conducted extensive research in the High Atlas and Anti-Atlas Mountains. His work shows that civilization arises not only in the urban and trading centers but also among the nomadic and desert populations in cultural exchanges that go far beyond national or colonial borders, which makes the distinction between “North African” and “Sub-Saharan African” meaningless. Flint’s work later led him to coin the transcultural term “Afro-Berber,” which was then replaced with the now preferred term “Afro-Amazigh” because it better describes the Indigenous peoples of this region and opposes the racist foreign designation used by the French colonial power. Artists associated with the Casablanca Art School combined the search for a specific Moroccan cultural identity with international aspirations and artistic and political solidarity between independent Arab nations. In 1974, the first Biennale of Arab Art took place in Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, at the Museum of Modern Art. Organized by the General Union of Arab Artists, it brought together artists from fourteen Arab nations and displayed over 600 artworks. Morocco was represented by fourteen artists related to Casablanca Art School who, rejecting popular trends in painting, were seen as the most vibrant and dynamic “new wave,” standing out for their lack of compromise with Socialist Realist iconography or Surrealist trends. The Moroccan delegation included, among others, Farid Belkahia, Saâd Ben Cheffaj, Mohammed Chabâa, Abdelkrim Ghattas, Miloud Labied, and Mohamed Melehi. The Casablanca artists extended communication with other Arab nations, organizing the second Biennale of Arab Art in Rabat, Morocco, in 1976. Two years later, Mohammed Chabâa and Mohamed Melehi designed the official poster for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in Beirut. Organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization, the exhibition displayed 200 artworks donated by artists from around thirty countries. Chaïbia Talal was Morocco’s most famous selftaught female artist, unattached to any schools or groups. Her work had been dismissed as “naïve” or folk art, but the artists of the Casablanca Art School appreciated it, sharing her interest in popular iconography and mythology. Mohamed Melehi and colleagues included Talal’s work in the exhibition Exposition nationale des arts plastiques at Rabat’s Galerie Nationale Bab Rouah in 1976 and invited her to participate in the 1986 arts and cultural festival Asilah Moussem Culturel. Liesbeth Bik and Jos Van der Pol have worked collaboratively as Bik Van der Pol since 1995. They see walking as an act of collective thinking that addresses questions of citizenship and publicness, as well as a mode of interweaving relationships between individuals, communities, and urban infrastructure within the context of broader discussions about decolonization and modernization.

Participating Artists: Carla Accardi, Malika Agueznay, Hamid Alaoui, Mohamed Ataallah, Herbert Bayer, Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, Saâd Ben Cheffaj, Ahmed Cherkaoui, Anna Draus-Hafid, André Elbaz, Abdelkrim Ghattas, Mustapha Hafid, Mohamed Hamidi, Abdellah El Hariri, Mohammed Kacimi, Miloud Labied, Mohamed Melehi, Houssein Miloudi, Ali Noury, Abderrahman Rahoule, Chaïbia Talal

Photo: Mohamed Melehi, Untitled, 1969, Oil on canvas, 75 x 111 cm, © Mohamed Melehi Estate. Courtesy of private collection, Marrakech / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Info: Curators: Morad Montazami, Madeleine de Colnet, Esther Schlicht and Luise Leyer, Associate researchers: Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa and Maud Houssais, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Römerberg, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Duration: 12/7-13/10/2024, Days & Hours: Tues & Fri – Sun 10:00-19:00, Wed-Thu 10:00-33:00, www.schirn.de/

Right: Mohamed Melehi, Untitled, 1969, Oil on canvas, 75 x 111 cm, © Mohamed Melehi Estate. Courtesy of private collection, Marrakech / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Right: Mohamed Hamidi, Composition, 1971, Acrylic paint on canvas, 99 x 63.5 cm, © The artist. Courtesy of private collection, Marrakech / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024