PRESENTATION: Mapping the 60s

The exhibition “Mapping the 60s” is based on the thought that substantial sociopolitical movements of the twenty-first century have their roots in the 1960s. Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, for example, have built on the anti-racist and feminist upheavals of yesteryear, as have current debates on war, mass media and mechanization, consumerism, and capitalism.

The exhibition “Mapping the 60s” is based on the thought that substantial sociopolitical movements of the twenty-first century have their roots in the 1960s. Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, for example, have built on the anti-racist and feminist upheavals of yesteryear, as have current debates on war, mass media and mechanization, consumerism, and capitalism.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: mumok Archive

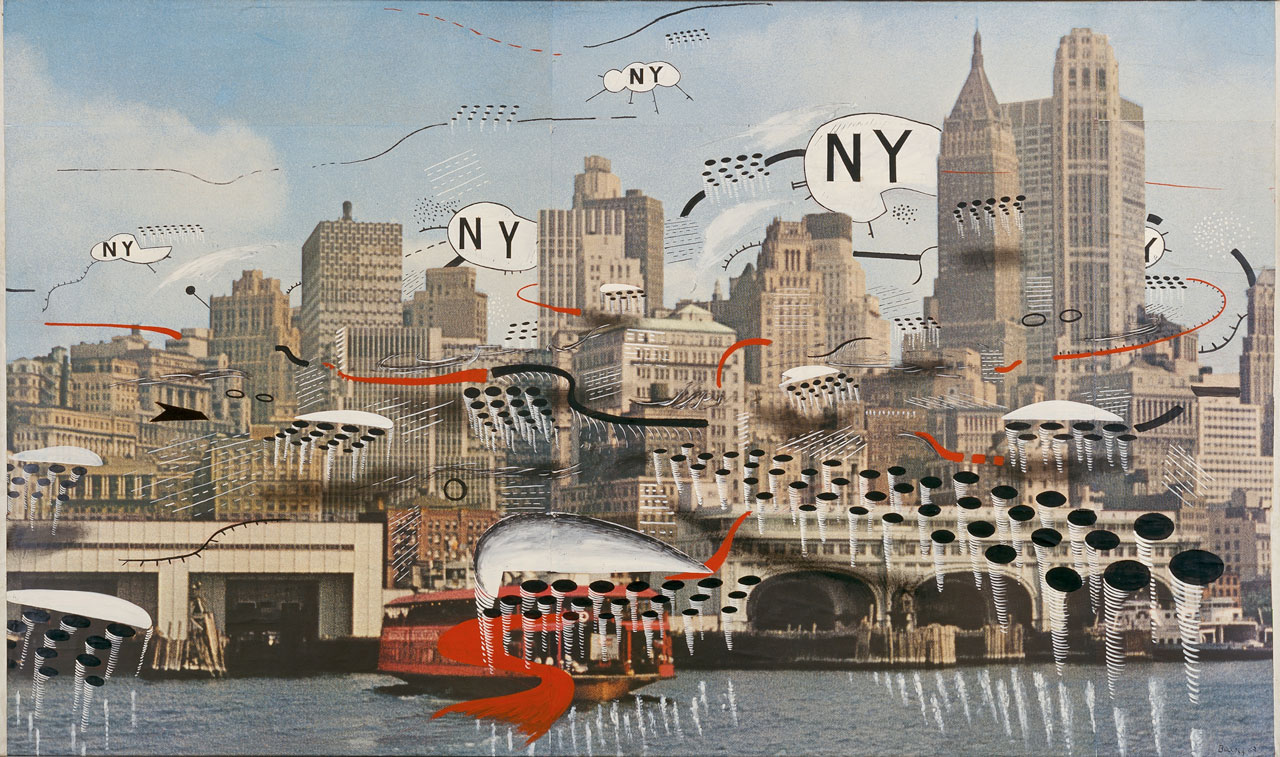

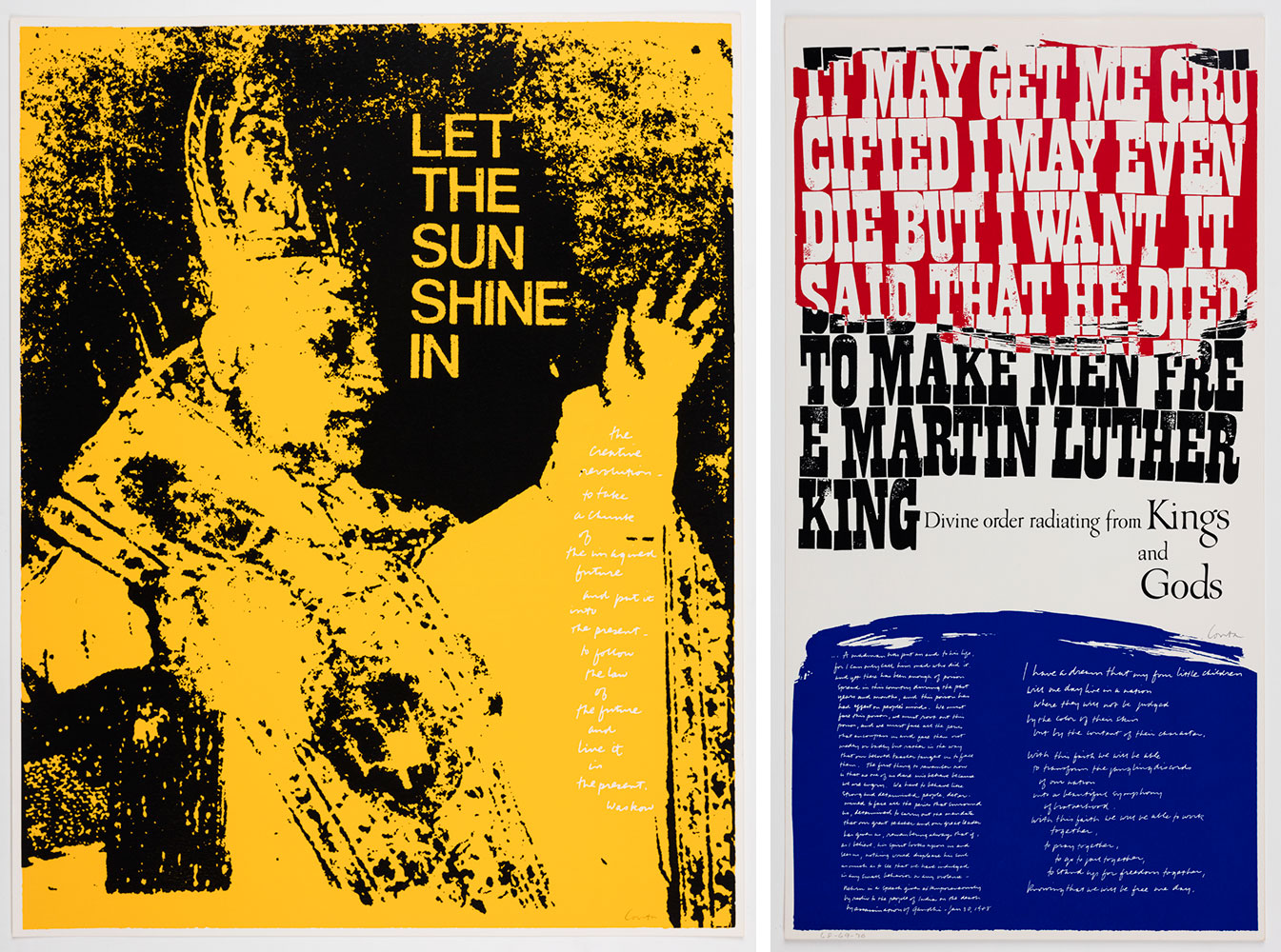

The developments of the 1960s in general and the events around 1968 in particular are not only paradigmatic in social and political terms, but also essential with regard to cultural policies. In 1962, the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts was founded in Vienna, a precursor of mumok, whose collection focuses on Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Vienna Actionism, performance art, Conceptual Art, and Minimal Art artistic movements of the 1960s. Even when we ask ourselves how to address art history today and make it productive, we encounter discussions that go back to that decade. As a presentation of the mumok collection, “Mapping the 60s” concentrates on the various new beginnings and upheavals that shaped this period, tracking down their traces within mumok’s holdings. In the spirit of the mapping cited in the title, i.e. cartography and surveying, the exhibits on display are contextualized within the setting in which they came into being. Key exhibitions and events of the 1960s are referenced, while in a further strand exemplary publication from this period turn the spotlight on significant discursive connections. This makes it possible to hone in on various aspects of that era as if setting them under a magnifying glass. Historical nodes of overlapping and intersecting socio-political concerns, aesthetic currents, and differing approaches are rendered visible – existing simultaneously, entering into exchanges yet also in opposition one to another. After years in which abstraction held sway, in the late 1950s artists turned their attention back to representational art, in the process encountering a contemporary reality in Western countries that was defined by an economic upturn, burgeoning consumerism, and all-encompassing mass media. In the context of Pop Art, images were now thematized as media-mediated material that circulated in newspapers, magazines and, above all, on television. Whereas Pop Art initially engaged with the sleek surfaces of the brave new world of commodities, advertising, and the associated structures of desire, during the 1960s it turned its gaze on the cracks in the facade of prosperity, fault lines within society, and the dark flipside of progress – sensationalism, violence, racism. However, Pop Art did not address these issues with a stance of outright opposition, instead always remaining aware that it formed part of precisely the media-oriented, economic, and social dispositive that it reflected. In the early 1960s, Andy Warhol turned his attention to violence and death in US society in what was known as his Disaster series. He relied on press photos – in “Orange Car Crash” (1963), which is shown here, an image of a car accident – and thus focused in particular on how media representations of cruel and violent events. The accident remains catastrophic, yet occurs on the same media level as the glittering depictions of stars and celebrities that Warhol in parallel found so fascinating. Death and violence are rendered visible as fundamental components of a society fixated on consumerism, the media and progress. Against the backdrop of the increasingly bitterly contested Vietnam War, a sculpture like Douane Hanson’s “Football Vignette” from 1969 does not address the presence of physical violence and brutality in US society directly but instead encodes it, in the form of three figures playing American football, frozen in motion in this depiction of a quintessentially American sport. Finally, Robert Indiana’s “Love Rising I Black and White Love (For Martin Luther King)” from 1968 is a statement against incessant racism and picks up on one of the critical defining events of US history in the 1960s: the assassination of Black civil rights activist Martin Luther King. Criticism of Pop Art, which was also accused at the time of being pro-consumerism and uncritical, does not do justice to the complex relationship between image, reality, and politics, as becomes particularly apparent in art such as the work by Corita Kent that has only recently entered the mumok collection. Kent, who was a Catholic nun in California for many years in the Order of the “Immaculate Heart of Mary” understood the accessible language of Pop Art and the relatively easy-to-use screen printing techniques inter alia as a means of conveying political messages to the people. Kent’s often colorful works, which rely on typographic elements and texts, quote Martin Luther King or Albert Camus; in the fraught political climate of the US in the 1960s, their advocacy of collective values like responsibility, devotion and charity represents an astonishing encounter between Catholic social philosophy and the rhetoric of a hippie movement that critiqued the ethos of individual achievement and the Vietnam War. To an even greater extent than books or catalogs, which are designed to be long lasting and serve as documentation, magazines offer a cross-sectional perspective thanks to their often periodical production and focus on current events at the time of publication. They create a public realm, provide space for public opposition, depict discussions and controversies, and, given that they are intrinsically collective in nature, are always an expression of social contexts and particular scenes. Magazines enjoyed a huge boom during the 1960s, especially in Western societies characterized by growing prosperity, rising consumption and ever-intensifying media communication. They were also an important medium for artists, with magazines’ specific traits increasingly becoming the focus of attention. Against the backdrop of a general shift within art towards the mass media, magazines and publications gave artists a chance to move beyond the closed, elitist circles of museums and galleries in order to reach a broader audience. “Aspen” is a prime example of this kind of magazine designed by artists. Ten issues were published at irregular intervals between 1965 and 1971; founder and editor Phyllis Johnson described the publication as a “magazine in a box”, as it was made up of a number of unrelated contributions in a wide range of media, bundled together in a cardboard box. Aspen was thus a kind of reproducible, mobile mini-gallery – another expression of the blurring of media boundaries during that era. The “1¢ Life” portfolio, on the other hand, stems from an extraordinary collective collaboration between New York and Paris, uniting trends as diverse as Abstract Expressionism, CoBrA, and Pop Art. Shanghai-born artist and poet Walasse Ting, who had spent time in Paris before moving to New York in the 1950s, where he associated with artists like Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel and Asger Jorn, teamed up with the painter Sam Francis for the 1964 publication. Together, the two organized contributions from a grand total of twenty-eight artists, including Enrico Baj, Oyvind Fahlstrom, Allan Kaprow, Kiki Kogelnik, Joan Mitchell, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, and Tom Wesselmann. The artists they invited to participate often responded directly to Ting’s poems, which make up a significant part of the publication. Reproductions of advertisements and postcard motifs were also incorporated into the visual program.

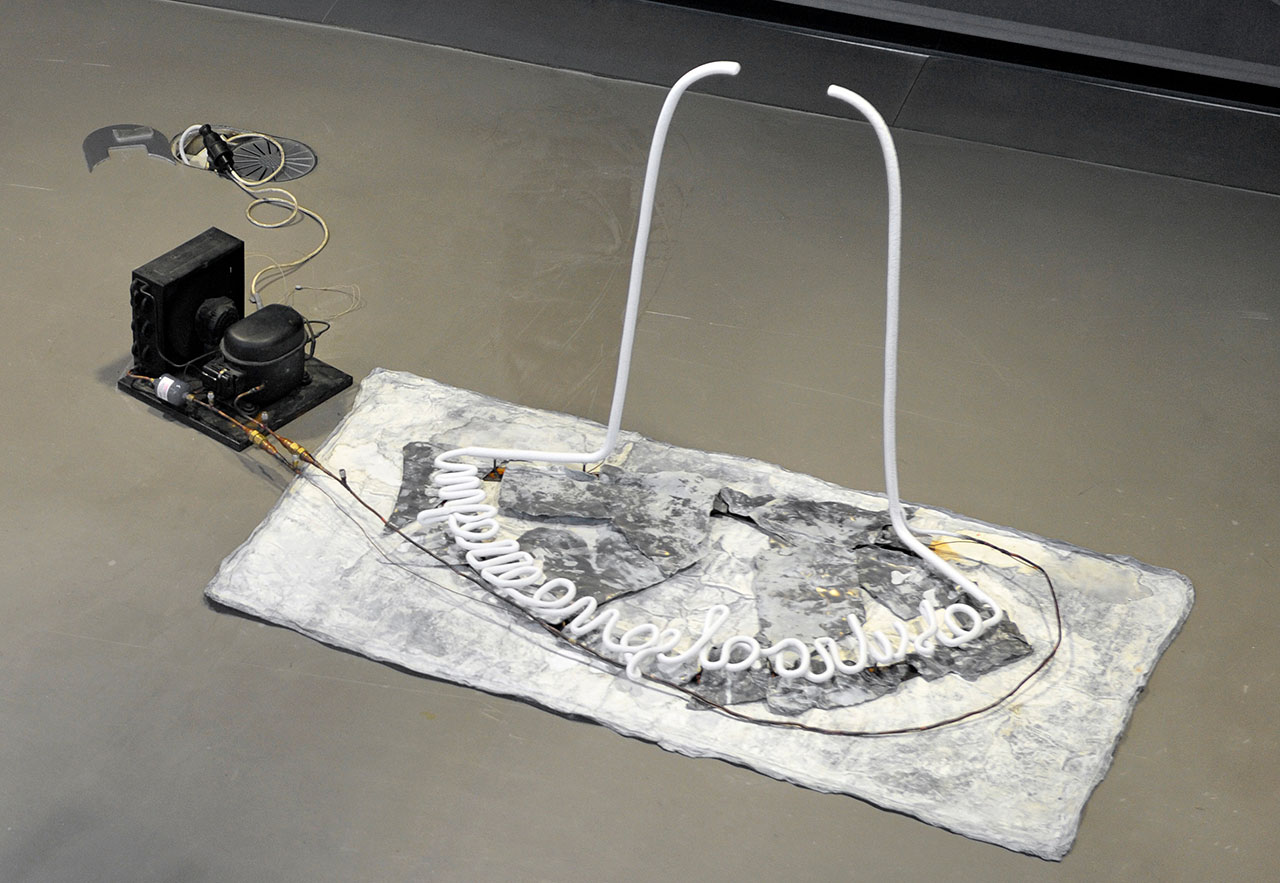

The fourth documenta was held in 1968, and the events shaping that turbulent year, with its student uprisings and demonstrations against the Vietnam War, continued to unfold against the backdrop of the “World’s Art Fair” in Kassel. In that spirit, there were repeated protests and heated discussions during the opening. The Milan Triennale and the Venice Biennale had faced similar controversies a little earlier. Artists used the press conference in Kassel to critique the absence of current developments such as Fluxus, Happening and Performance in the exhibition. They lambasted documenta, perceiving it to be too close to the market and overly complacent and in addition alleging that it predominantly included works from the USA, particularly from the Pop Art context, rather than from Europe, especially West Germany. That accusation earned documenta 4 the nickname “Americana.” In fact, artists from the USA made up around one-third of the exhibition. From today’s point of view, however, it seems more striking that there were only five women among the 150 participating artists. Director Jef Cornelis made more than 200 films in over 30 years that he worked for Belgian broadcaster BRT. Many addressed the visual arts, especially his initial works before the early 1970s. In 1968, Cornelis made one of his films about documenta 4 in Kassel. Many of the key players at the time have an opportunity to comment in the film, such as documenta founder Arnold Bode and Jean Leering, the young director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, who had been appointed to the documenta Advisory Council to help rejuvenate the exhibition. In addition, the film shows art critics such as Pierre Restany, gallery owner Denise Rene, and curator Harald Szeemann, who was at the helm of the following documenta 5 in 1972. Above all, however, Cornelis gave artists participating a chance to have their say. Impressions of the exhibition being set up are captured in the film along with the controversies sparked by documenta 4. In one-to-one interviews with Christo, Joseph Beuys, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Rauschenberg, Cornelis focused on some specific voices in the exhibition. These conversations with the artists also reveal their underlying approaches, methods and, in some cases, production contexts. A nuanced picture of the mood emerges, as Cornelis also captures how disgruntled some artists felt. Over and above obvious sources of strife, such as arguments about better placement and purported preferential treatment, the overarching fault lines of the era also become visible, emerging above all in relation to politicization of art. Where some advocated arguing in the narrower political sense and jockeying for position, others tended instead to deploy smoothly ironic and sometimes subtly critical affirmations. On September 20th, 1962, the Museum of the 20th Century, later known as mumok Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, opened in Vienna. At the time the museum, soon known as the “20er Haus,” was the only art institution in Austria that focused exclusively on twentieth-century art. It was housed in a functional, modernist building, originally designed by Austrian architect Karl Schwanzer as a pavilion for the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels and subsequently slightly modified for its reconstruction in the Schweizergarten in Vienna. During the early years, the museum’s exhibition and collection policy was significantly influenced by founding director Werner Hofmann, who was at its helm until he moved to Hamburger Kunsthalle in 1969. Three years before the new museum’s official opening, Hofmann had already begun building up an appropriate collection of modern art. These acquisitions and the exhibition history for his time as director (1962-1969) display a particularly striking focus on sculpture that was quite unusual at the time. Hofmann organized large-scale overview exhibitions of sculpture such as “Plastiken von Rodin bis heute” (1966-1967) or “Plastiken und Objekte” (1968), which directed attention to international developments in sculpture, and in addition regularly showed individual presentations of Austrian sculptors such as Fritz Wotruba, Rudolf Hoflehner, Wander Bertoni and Roland Goeschl. In 1969, an exhibition was held at Kunsthalle Bern that is ranked as one of the most important in recent art history: “Live in Your Head – When Attitudes Become Form. Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information”. Curator Harald Szeemann brought together a new generation of artists such as Hanne Darboven, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Richard Long, Richard Serra, and Franz Erhard Walther who distanced themselves from the social and mass-media focus of Pop Art and from the purist and self-referential Minimal Art of previous years. These artists concentrated on concepts, processes, and changeability, on ephemeral events or even solely on linguistic, photographic or numerical instructions or information. This new understanding of art emphasized above all the artistic idea and artistic action. Art was viewed as a temporary process with an open-ended outcome that was largely determined by the materials used and did not necessarily result in a completed and “commodified” work. Although “When Attitudes Become Form” was by no means the only exhibition dedicated to this radically new art, it is considered a key event in the history of exhibition-making and the advent of the modern concept of curating; in 2013, restaged was even restaged at the Fondazione Prada in Venice. The exhibition played a pioneering role in developing process-oriented forms of production and presentation, with the exhibition space functioning as a kind of collective and open studio where many of the works came into being for the first time. However, “When Attitudes Become Form” entirely failed to fulfill today’s diversity standards; almost all the artists originated from the USA or Western Europe and the sixty-nine artists listed in the catalog included just three women: Hanne Darboven, Eva Hesse, and Jo Ann Kaplan.

Photo: Pino Pascali, Il muro del sonno, 1966 , 250 x 330 x 19 cm, Cushions, foam, rubber, paint and wood, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, On loan from the Austrian Ludwig Foundation, since 1981, © Fondazione Pino Pascali

Info: Curators: Manuela Ammer, Marianne Dobner, Heike Eipeldauer, Naoko Kaltschmidt, Matthias Michalka, Franz Thalmair, mumok (Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien), Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 5/7/2024-1/2/2025, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 10:00-18:00, Wed 10:00-20:00, www.mumok.at/

Right: Robert Indiana, Love Rising / Black and White Love (For Martin Luther King), 1968, acrylic on canvas, each piece: 183 x 183 x 9 cm, in total: 367 x 367 x 9 cm , mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, On loan from the Austrian Ludwig Foundation, since 1991, © 2024 Morgan Art Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Bildrecht, Wien 2024

Right: Corita Kent, let the sun shine, 1968, 73.8 cm x 58.7 cm, Screenprint, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, acquired in 2020, © Bildrecht, Wien 2024

Right: Sine Hansen, On Top, 1967, 130 cm x 120 cm x 2.8 cm, Egg tempera on canvas, mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, On loan from the Austrian Ludwig Foundation, since 2021, © Nora Meyer