ART CITIES: N.York-Keith Sonnie

Keith Sonnier reinvented sculpture in the late ‘60s. Employing unusual materials that had never before been used, Sonnier, along with his contemporaries, called all previous conceptions of sculpture into question. In 1968, the artist began working with neon, which quickly became a defining element of his work. The linear quality of neon allows Sonnier to draw in space with light and color, while the diffuseness of the light enables his work to interact on various architectural planes. Sonnier’s architectural neon installations in public spaces have earned him wide acclaim in an international context.

Keith Sonnier reinvented sculpture in the late ‘60s. Employing unusual materials that had never before been used, Sonnier, along with his contemporaries, called all previous conceptions of sculpture into question. In 1968, the artist began working with neon, which quickly became a defining element of his work. The linear quality of neon allows Sonnier to draw in space with light and color, while the diffuseness of the light enables his work to interact on various architectural planes. Sonnier’s architectural neon installations in public spaces have earned him wide acclaim in an international context.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: David Kordansky Gallery Archive

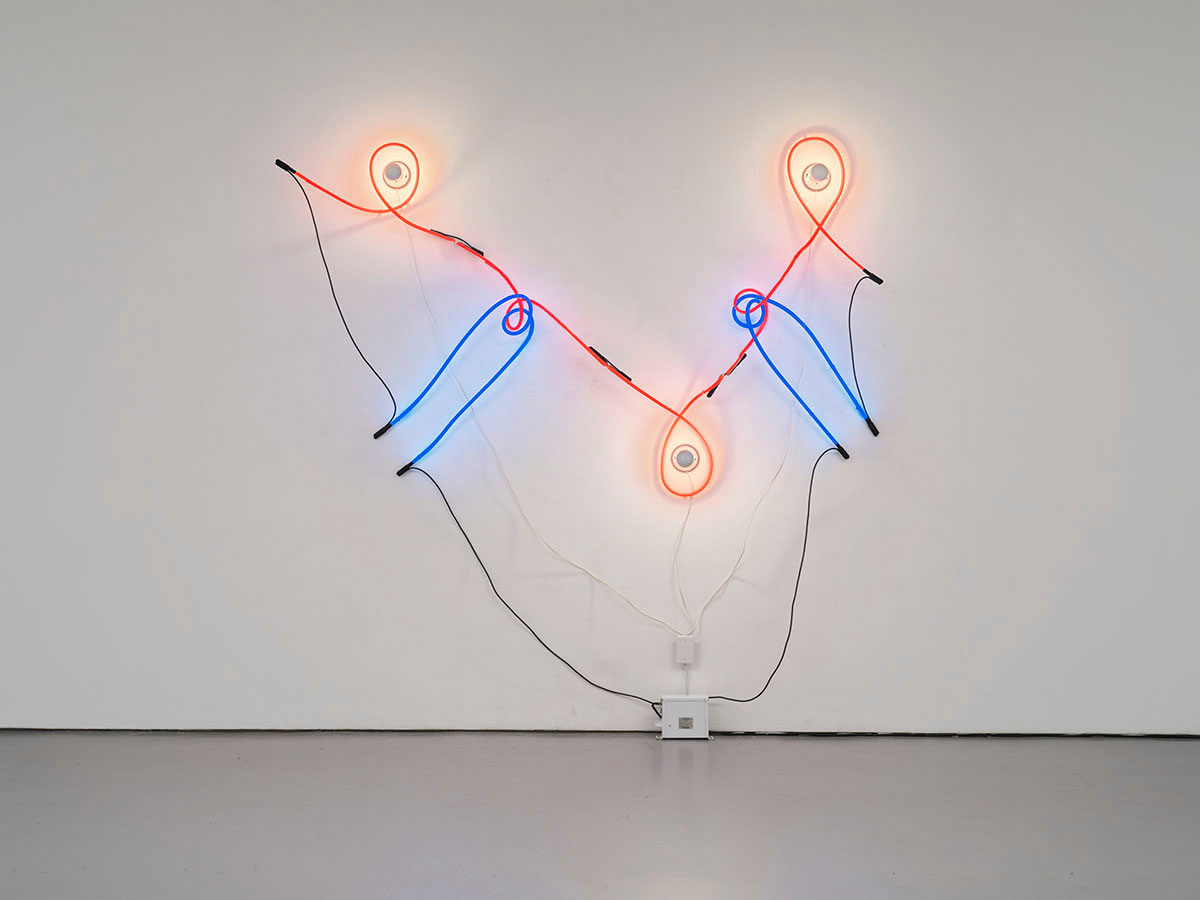

In the exhibition “Inside Light, 1968–1970″ are on view important works by Keith Sonnier, whose unique vision encompassed advances in sculpture, painting, installation, and performance. Best known for his pioneering use of light, Sonnier authored a complex body of work that challenges dogmas at the heart of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art historical narratives. His association with the artists grouped under the post-Minimalist rubric provides some insight into a mind that understood materials according to their innate properties as well as the cascading reverberations of associations they make in the realms of human perception and culture. The exhibition focuses on a three-year period between 1968 and 1970 in which Sonnier first began working with neon and argon and made many of the breakthroughs that would define his career. Sonnier was born in the Cajun town of Mamou, Louisiana, and moved to the northeastern United States in the mid-1960s to study art at Rutgers University, then a nexus for artistic experimentation. Among his artistic colleagues were artists like Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Richard Tuttle, and Jackie Winsor who were also dedicated to pursuing the use of non-traditional and often ephemeral materials, and who conceived of their projects as multi-genre experiments in which site-specific installation and interaction with surrounding architecture informed the conception and production of works. For Sonnier, who would go on to live and work in New York City and Bridgehampton, New York for the remainder of his career, the incorporation of light became a way of engaging directly with the environments where his work was viewed. It also enabled him to maintain an ongoing connection to formative sensory experiences he had growing up in Louisiana, where he recalled seeing the lights of signs interacting in mysterious and moving ways with the landscape and weather. The fixtures and wiring that powered and supported the bulbs, meanwhile, became parts of a vocabulary of abstract gestures notable for their intuitive humor, surrealism, and quasi-figurative echoes. This placed his work in dialogue with an international group of peers, such as the artists associated with Arte Povera in Europe, for whom the rawness and informality of certain materials were providing the foundation for new, surprising, and paradoxical kinds of formal sophistication and subtlety. This wide-ranging sensibility, as expansive as it is idiosyncratic, led to Sonnier’s inclusion in important group exhibitions, among them “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form”, organized by Harald Szeeman at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, and the American Pavilion at the 36th Venice Biennale in 1972, where he exhibited alongside a heterogeneous group of artists, including Diane Arbus, Sam Gilliam, and Jim Nutt, selected by curator Walter Hopps. By this time, Sonnier had begun to produce works like “Neon Wrapping Incandescent VI” (1968), in which he arranged neon and incandescent bulbs in ways that foregrounded the hands-on manipulation of materials and free-flowing compositions. He bent copper rods to provide templates for neon fabricators to follow and placed the two kinds of bulbs—and the distinct varieties of light they emit—in conversation with each other, generating not only geometric patterns and quasi-pictorial images, but a field of perceptual information that immerses the viewer’s body in a constantly changing experience. In this way, Sonnier posed post-modern questions about the role of art and the means by which art functions in particular kinds of spaces, even as he addressed time-honored formal problems of perspective, illumination, and illusion. Works like “Untitled Neon Corner Piece” (1969) gave Sonnier the opportunity to create intersections between otherwise diverging paths. The installation of neon tubes, aluminum supports, and associated fixtures is, on the one hand, a bracing minimalist composition that draws attention to the qualities of its own components as well as their relationship to the corner in which the artist has fitted them. On the other, though, it reflects his lifelong interest in the burgeoning possibilities of technology, both in terms of form and content. By covering the tubes with paint at specific intervals, Sonnier made a link to the dots and dashes of Morse code, which defined the sound and feel of early radio telegraphy throughout the twentieth century and constituted a crucial means of communication during World War II. For an artist born during the war, Sonnier also provided a sensory connection to global events and the epoch-changing dynamics that continued to evolve as technological change only accelerated over the course of his life. Such connections reveal the degree to which Sonnier combined non-objective aesthetics with an awareness and affection for cultural observation ordinarily associated with Pop art. In a 2015 interview, for instance, he noted that his passion for artmaking was driven by a desire to keep “reading the culture that I’m in.” Sonnier localized and particularized abstraction in ways that make it equally surprising, accessible, and personally resonant to its viewers. The foundational “Ba-O-Ba works”, whose title refers to a Haitian French expression that Sonnier translates as “the effect of moonlight on the skin”, are a case in point. Their shaped, reflective sheets of glass offer physical and optical counterpoints to the neon tubes installed around them and set up complex and subtle relationships between the wall against which they lean and the radiant fields of light that emerge around and behind the glass. Because they establish dialogues in two and three dimensions, they can be read alternately as pictures or as sculptural constructions. But they also seem to make room for the existence of another category, one in which the experience of the physical world is, like the thoughts and emotions that animate the people who interact with it, equally dependent on immaterial forces. For Sonnier, innovation had roots in the humanities and sciences alike, and his wide-ranging sensibility allowed him to bring together ways of making and seeing that, considered together, generated new possibilities that are increasingly influential for younger artists across many disciplines and theoretical positions.

Photo: Keith Sonnier, Neon Incandescent VI, 1968, argon and neon tubes, porcelain fixtures, incandescent bulbs, light switch, transformer, and electrical wire, 105 x 104 x 8 inches (266.7 x 264.2 x 20.3 cm), © 2024 Keith Sonnier / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery

Info: David Kordansky Gallery, 520 West 20th Street, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 22/6-9/8/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.davidkordanskygallery.com/