PRESENTATION: Avant-Garde and Liberation

The exhibition “Avant-Garde and Liberation” highlights the significance of global modernism for contemporary art. It raises questions of the political circumstances that move contemporary artists to resort to those non-European avant-gardes that formed as a counterpart of the dominant Western modernism from the 1920s to the 1970s. What are the potentials artists see in the ties to decolonial avant-gardes in Africa, Asia, and the “Black Atlantic” region, to take a stand against current forms of racism, fundamentalism, or neocolonialism? Which artistic methods are employed when addressing subjects such as the encroachment on personal liberties and social cohesion by drawing on seminal anticolonial and antiracist positions of the early to mid-twentieth century?

The exhibition “Avant-Garde and Liberation” highlights the significance of global modernism for contemporary art. It raises questions of the political circumstances that move contemporary artists to resort to those non-European avant-gardes that formed as a counterpart of the dominant Western modernism from the 1920s to the 1970s. What are the potentials artists see in the ties to decolonial avant-gardes in Africa, Asia, and the “Black Atlantic” region, to take a stand against current forms of racism, fundamentalism, or neocolonialism? Which artistic methods are employed when addressing subjects such as the encroachment on personal liberties and social cohesion by drawing on seminal anticolonial and antiracist positions of the early to mid-twentieth century?

By Efi MIchalaro

Photo: Mumok Archive

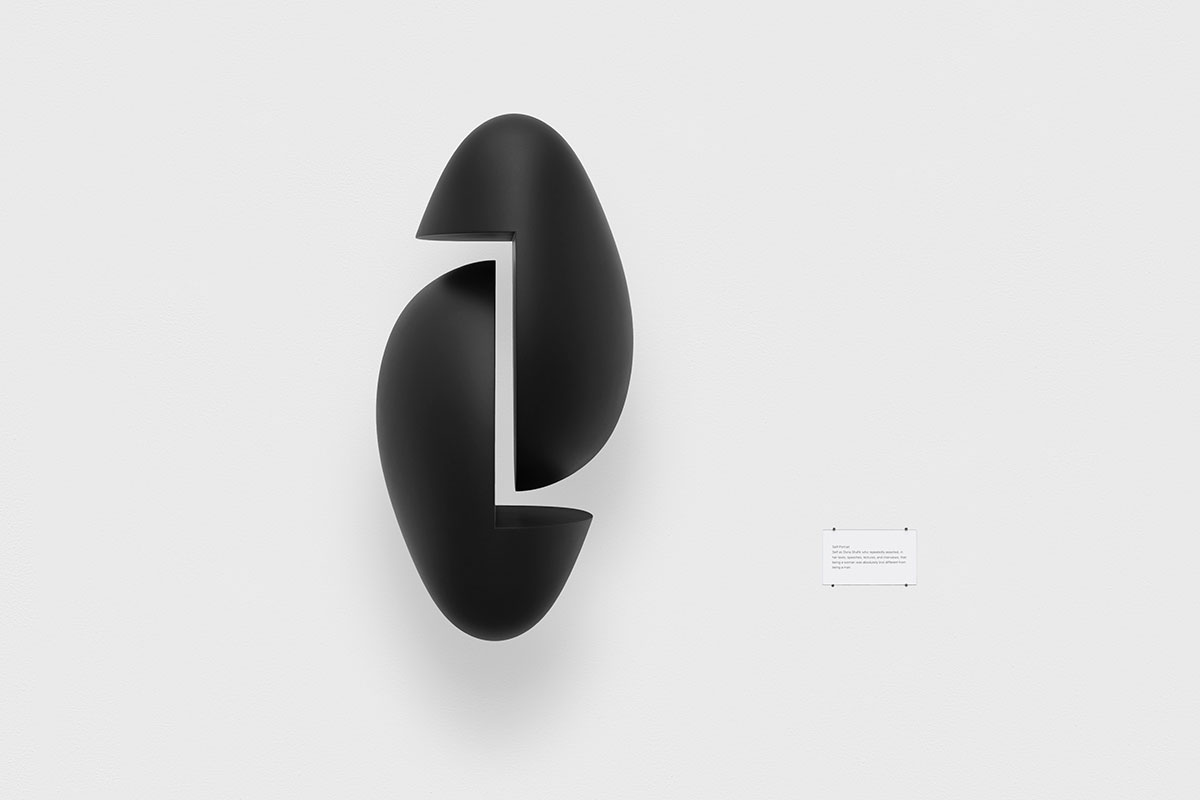

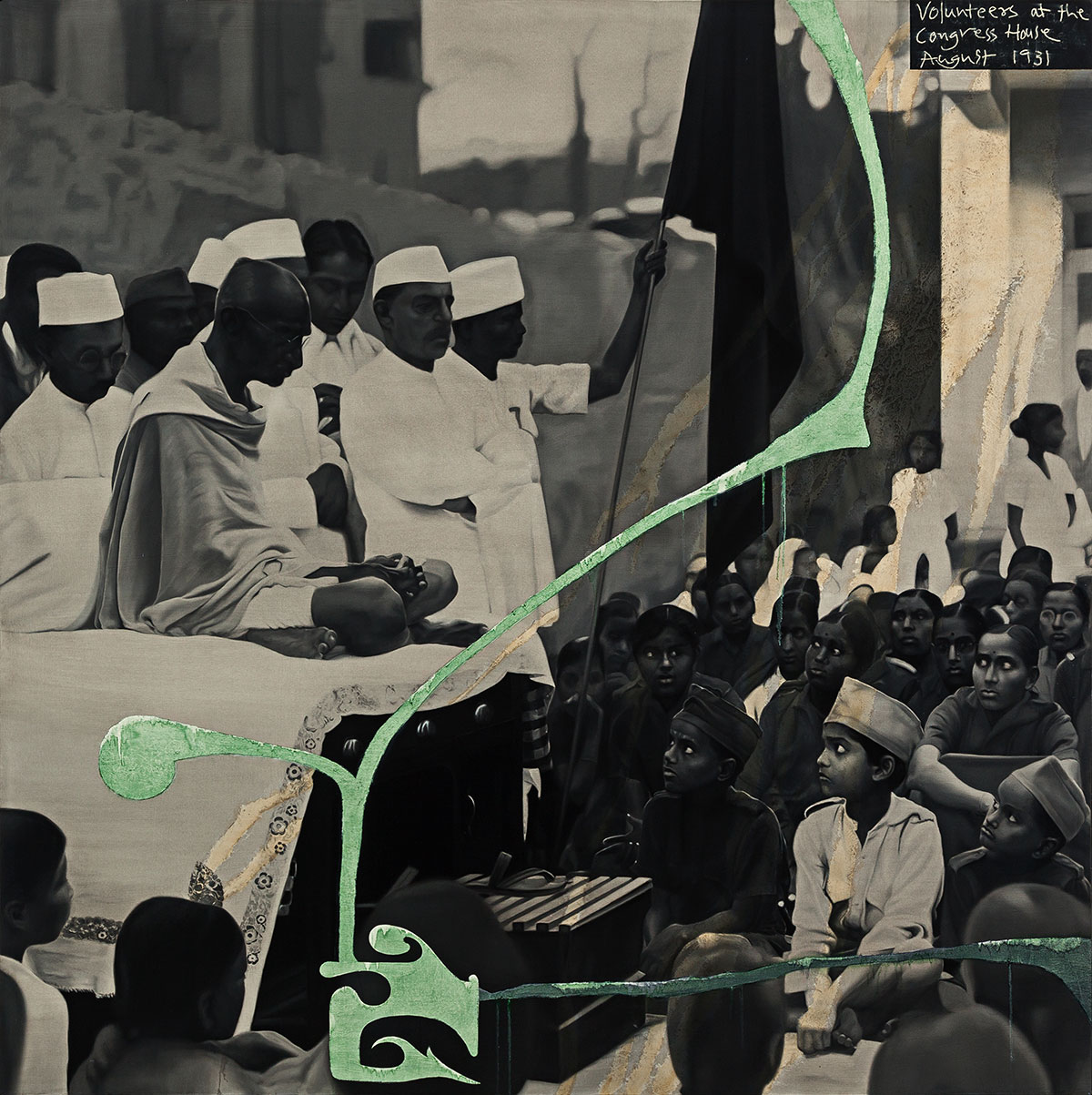

Featuring a broad spectrum of artistic methods, media, and aesthetics, “Avant-Garde and Liberation” seeks to create a space in which to reflect upon radical artistic and intellectual ventures within the historical context of decolonization. The various works are connected by their interest in questions of temporality and the relationship between past, present, and a possible better future. For Western avant-garde movements, the orientation towards the new had to do with a historical breaking with, and overcoming of, traditions. While decolonial avant-garde movements from the 1920s to the 1970s were concerned with renewal and liberation as well, their revolutionary impulse was also closely intertwined with the reconstruction of histories that colonial forms of knowledge had distorted and a restored connection with the cultural heritage of their forebears. As the artworks in this exhibition make clear, it is not enough to simply expand our conception of the avant-garde to encompass global modernism. What is required is a fundamental rethinking of what constitutes the “avant-garde” through a decolonial lens. Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc’s work reconstructs the unfinished film “Guns for Banta” (1970) by Sarah Maldoror, the legendary French director from Guadeloupe. The film told the story of the struggle and death at a young age of Awa, a country girl who joins the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde and fights for the liberation of Guinea-Bissau. Maldoror’s film was commissioned by the Algerian government, but a conflict between the director and the client prevented it from ever being completed. The only material evidence of its existence consists of photos taken by war photographers on the film set. Abonnenc’s work seeks to restore the collective memory of Maldoror’s unfinished film, whose main goal was to portray the involvement of women and children in the struggle for independence. The photos are complemented by a voiceover conversation between Abonnenc, the director, and the latter’s ex-partner, Angolan writer Mário Pinto de Andrade. The work by Omar Ba is an impressive painted memorial to the era of African decolonization and to Cheikh Anta Diop as one of the leading intellectuals of that movement. Against the backdrop of a world map and Western buildings from the era of imperial modernity, such as the Eiffel Tower and Big Ben, we see three figures in West African dress. In between them, artworks from ancient Egypt are depicted on narrow pedestals. Omar Ba is alluding here to the academic research carried out by the Senegalese anthropologist and historian Diop, who posited a historical connection between the cultures of sub-Saharan Africa and those of Egypt, which Western discourse has always described as white or Hamitic. Starting in the nineteen-fifties with publications such as “Nations nègres et culture” (The African Origin of Civilization), Diop characterized Egyptian civilization as Black and attempted to demonstrate its influence on Greek antiquity. Black history and cultural lore are the central themes of Radcliffe Bailey’s art. Exploring subjects ranging from traditional African art and the history of slavery, to the anti-colonial revolutions and liberation movements in the USA, and onward to African American music, the artist has since the nineties dealt with many different facets of this history of violence and resistance in his paintings, sculptures, and installations. Bailey conceives of memory as a medicine for treating the disease of racism. His sculpture “Untitled” (2010) commemorates the Haitian revolutionaries Toussaint Louverture and Jean- Jacques Dessalines, who around 1800 overthrew French colonialism and founded the first free Black Nation in the Americas. Bailey’s use of glitter in his work alludes to the spiritual and healing practices of Haitian voodoo. “Mahalia” (2021) is a pictorial tribute to the gospel singer and civil rights activist Mahalia Jackson. The structure of the image was inspired by the famous quilts of Gee’s Bend in Alabama. Characteristic of Bailey’s process is the fusion here of musical and textile techniques of Black resilience, for which he also draws on his childhood memories of living in his grandparents’ home. In the tumultuous summer of 1966, Yto Barrada’s mother, a twenty-three- year-old Moroccan student, was one of fifty “Young African Leaders” invited by the US State Department on a tour of the USA. Through play, poetry, and humor, the film “Tree Identification for Beginners: explores this staged encounter between North America and Africa and the burgeoning spirit of disobedience that would shape an entire generation—as expressed by the Pan-African, Tricontinental, and Anti-Vietnam War movements. The film combines 16 mm stop-motion animation using Montessori toys with voiceovers by Barrada’s mother and other Crossroads Africa participants, as well as by historical figures such as Black Panther Stokely Carmichael. “Untitled (Nougat Cross Section Flavor Sampler) (2016), Barrada’s sculptural work made of Moroccan candy, relates to sculptures from the nineteen- sixties by Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair, now considered” a central figure in Arab modernism.

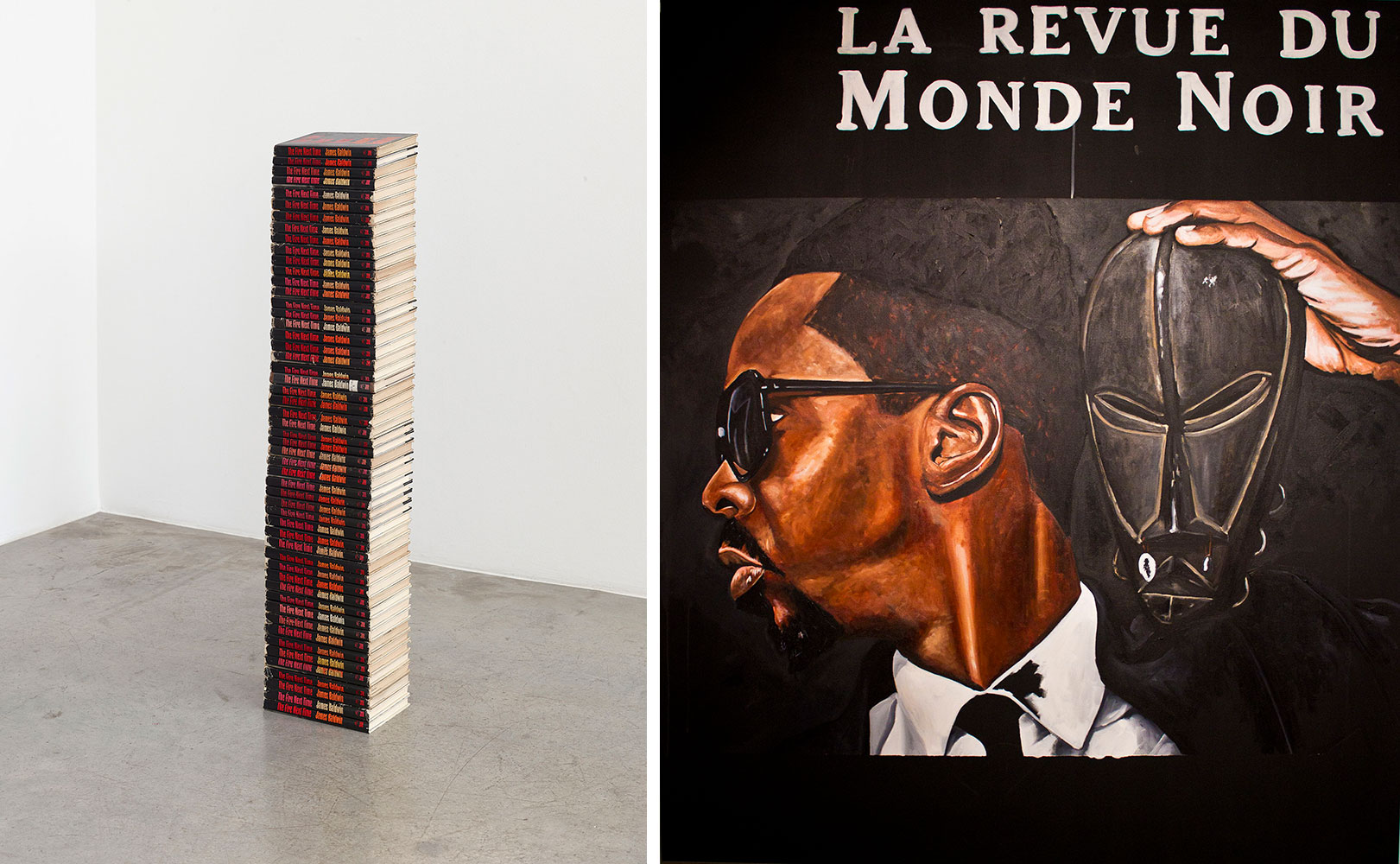

In “Insectopia” Robert Gabris responds to the impositions and attributions that an artist whose work evokes the experience of a queer Rom*nja person must face in many art institutions in a society marked by racist and sexist notions. The body prints allude to scientific and police practices of collecting and classifying plants and animals—and ultimately also humans, who have been made into exhibits and study objects as a way to exert control and power over those who deviate from the bourgeois and heterosexual norm. The artist expresses his “skepticism about anthropology, ethnography, and the institutional power of museums” in works on paper, large fabric panels, and a video of a performance in Florence. Using the technique of the body print, Gabris recalls the Body Prints made by the African American artist David Hammons as part of the Black Arts Movement of the nineteen-sixties. The political awakening of African countries during the independence era brought with it new forms of expression in literature, film, art, and photography, as well as a specific building culture. As in the other arts of decolonization, the architecture of the nineteen-sixties and -seventies features forms and concepts that stood for liberation and pointed to the future of African societies after the end of colonialism. In “Avant-Garde City: (2023), Jojo Gronostay looks at examples of avant-garde architecture in cities such as Accra, Abidjan, and Dakar. Modernist and brutalist buildings dating from the independence era appear here—as if casually taken from the movement—among examples of profane functional construction and built manifestations of globalized capitalism. Gronostay, who for many years has been examining neocolonial aspects of the circulation of people and goods between Europe and Africa, shows us the architectural avant-garde of decolonization in an urban context. The way the work is displayed in the exhibition space furthermore calls to mind the freestanding video walls that ply us in popular shopping streets with moving advertising images. For the photo series “Channelling (Vienna)” (2023), Janine Jembere photo- graphed artists in Vienna with their eyes closed. As viewers, we look into the faces of the portrait subjects but not into their eyes, giving us the feeling that they see more than we do. As if they were in spiritual contact with deceased or distant persons, the sitters meld with artists, musicians, and poets from the liberation movements of the twentieth century, including the anti-colonial filmmaker Sarah Maldoror and the African American artist Faith Ringgold. Jembere made her analogue photographs after speaking with each portrait subject about the respective historical person who inspired them. “Channelling (Vienna)” thus serves to spotlight the continuity of resistance movements and the strength gained from community. For “Tipping Point”, Zoe Leonard collected fifty-three copies of the first edition of James Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time (1963) and arranged them in a stack. The number of books corresponds to the years that elapsed between the publication of Baldwin’s book on the destructive power of racism in the USA and the execution of Leonard’s work. The artist, whose work has since the eighties subtly addressed instances of oppression and resistance, had long been preoccupied with Baldwin’s famous warning to American society. Appalled by the numerous police killings of unarmed Black people in the twenty-tens, Leonard then felt compelled to turn Baldwin’s book into a work that, like few others, articulates both simply and yet with deep complexity the timeliness of historical struggles. The form taken by the sculpture is reminiscent of Minimal Art objects that came to the fore simultaneously with Baldwin’s Fire Next Time, also calling to mind their seriality. In “Tipping Point”, however, the motif of repetition is to be understood politically: How many more times does this warning, voiced frequently since Baldwin, still have to be repeated? And when will the social tipping point be reached?

Participating Artists: Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Omar Ba, Radcliffe Bailey, Yto Barrada, Mohamed Bourouissa, Diedrick Brackens, Serge Attukwei Clottey, william cordova, Atul Dodiya, Robert Gabris, Jojo Gronostay, Leslie Hewitt, Iman Issa, Janine Jembere, patricia kaersenhout, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Zoe Leonard, Vincent Meessen, The Otolith Group, Fahamu Pecou, Cauleen Smith, Maud Sulter, Vivan Sundaram, Moffat Takadiwa

Photo: Moffat Takadiwa, The Occupation of Land, 2019, Found computer keys, toothbrushes, and plastic bottle tops , 304,8 x 365,7 x 17,8 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles/Bucharest; photo: Lee Tyler Thompson

Info: Curator: Christian Kravagna and Matthias Michalka, Mumok (Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien), Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 7/6-22/9/2024, Days & Hours: Tue & Thu-Sun 10:00-18:00, Wed 10:00-20:00, www.mumok.at/

Right: Fahamu Pecou, A.W.N. (Artist with Negritude), 2012, Acrylic on canvas, 178 × 147 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Backslash, Paris, © Backslash, Paris