ART CITIES: Los Angeles-Jerry Peña

Jerry Peña is a first-generation Mexican American artist, who explores family history, the history of Los Angeles, tensions of identity and assimilation, and his working class socioeconomic status within his work. His artwork incorporates found objects and employs textures and color as well as material experimentation that descends aesthetically from Southern California’s Custom car culture, Rasquachismo*, Abstract Expressionism to Post Minimalism.

Jerry Peña is a first-generation Mexican American artist, who explores family history, the history of Los Angeles, tensions of identity and assimilation, and his working class socioeconomic status within his work. His artwork incorporates found objects and employs textures and color as well as material experimentation that descends aesthetically from Southern California’s Custom car culture, Rasquachismo*, Abstract Expressionism to Post Minimalism.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Charlie James Gallery Archive

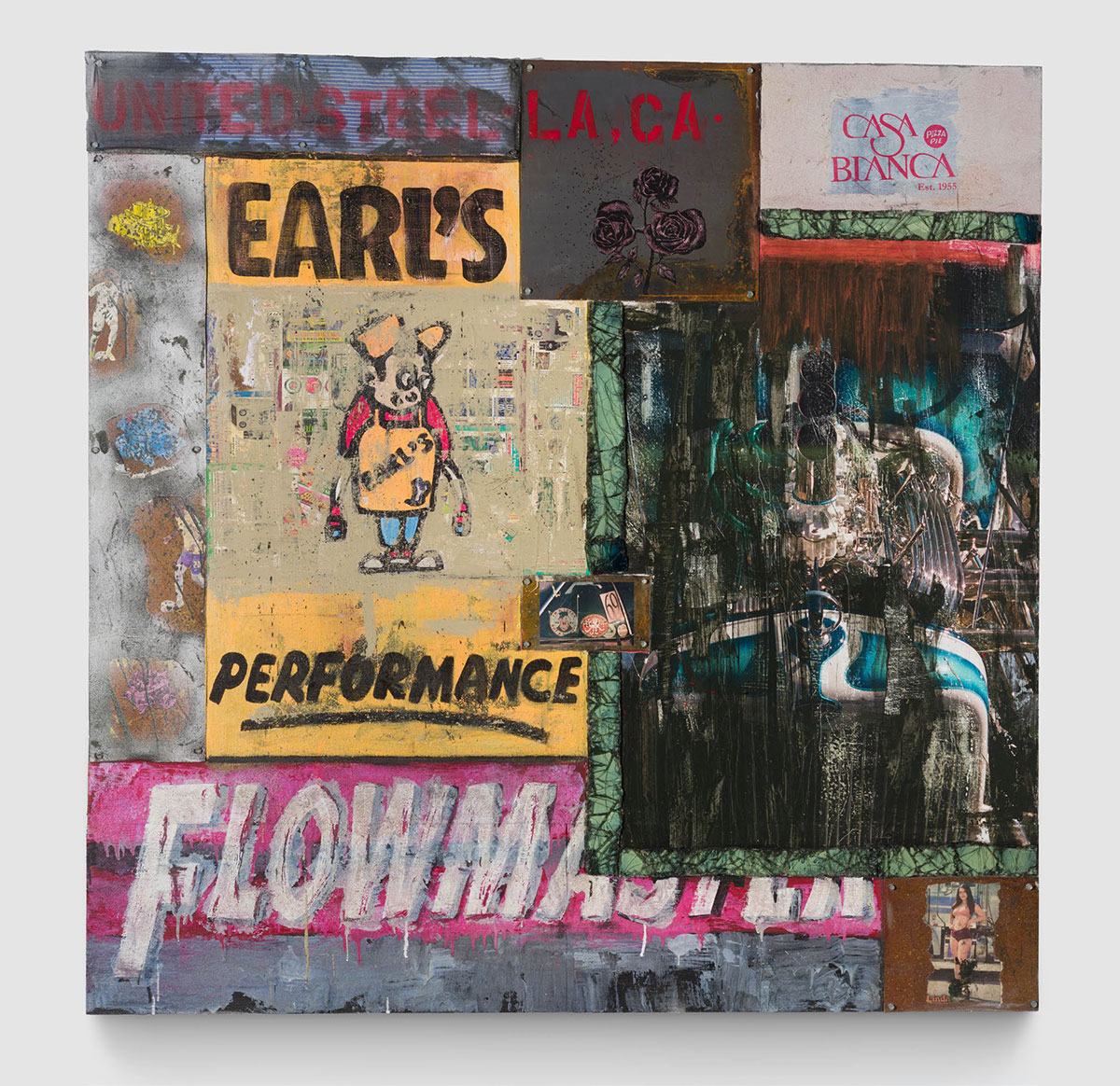

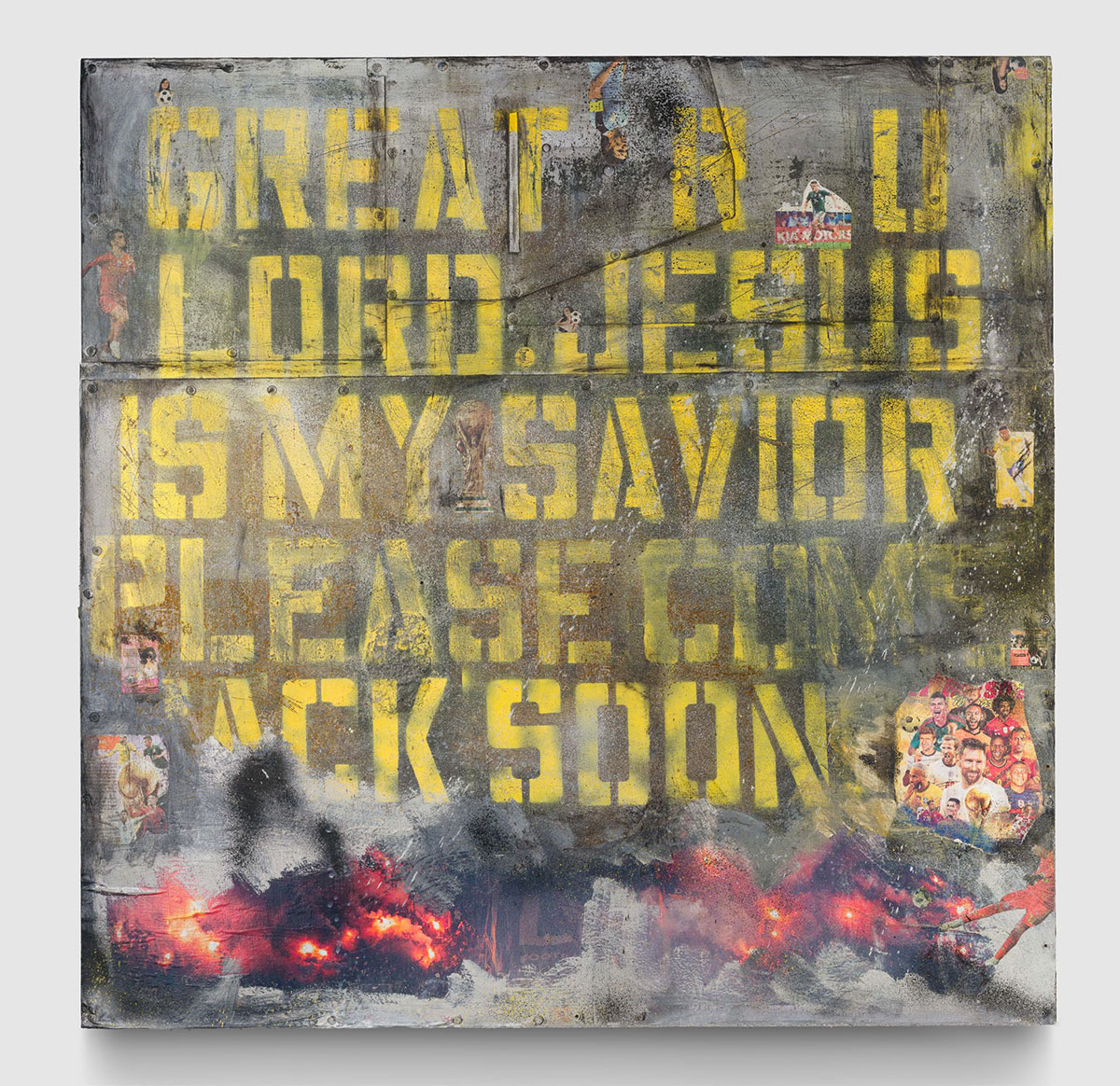

Jerry Peña in his exhibition “A Rose By Any Other Name” presents wall-based works that merge painting, photography, and found materials in compositions that spring from the artist’s keen observations of the psychological and physical landscapes that surround him. The works aesthetically descend from Robert Rauschenberg’s Neo-Dada inventions, combining the materials of art and life to create something more than either alone. Peña employs the textures, colors, and materials of working class Los Angeles in experimental, expressionist compositions that speak to his own family history, the history of the city, and the tensions of identity and assimilation. His work pieces together hallmarks of Americana – the cars, beers, and teams that garner followings so loyal that they become signifiers of self – which Peña then complicates through local specificity and material invention. A deep sense of place suffuses the work, which evokes a particular Los Angeles built on hard labor and fierce pride. This is the artist’s first exhibition with the gallery. Cars are a throughline in Peña’s work, made manifest not only in the accoutrement of auto body shops and collaged photographs, but also in more material ways. The surface of “Welcome to Chavez Ravine” is seen almost entirely through the spidering cracks of a busted windshield, a discarded remnant of vehicular violence or mishap that can often be found littering the streets of Los Angeles. The cracked glass comes close to obliterating the image behind it, but the interlocking letters of the Dodgers logo loom large, and the artist’s own Dodger hat is affixed at the bottom right of the composition. Peña sees this work as a kind of ofrenda to fanhood, a devotional space that honors a favored team and its deep roots in the city. This commingling of sports and religious fervor is made even more apparent in Catholic Guilt and Footie Fever, which includes a stenciled prayer over images of soccer heroes and rioting soccer fans. Windshield glass also appears in “Sinister Purpose”, a composition in three registers that evokes the souped-up grill of a classic hot rod as much as it does the formal experimentations of Mexican painter José Clemente Orozco’s 1930’s abstractions. Peña’s painterly skills come to the fore here. He borrows a niche technique from lowrider finishing that uses dish soap to repel paint, leaving the swirling traces of liquid permanently visible. Peña sands down the entire surface, lending it a lived-in, aged feel. Personal history comes through as well: roses lifted from the signage of the bakery from his childhood neighborhood masquerade as something like headlights in the bottom register, while the cartoonish logo of the Moon Eyes hot rod fabrication shop peer down from the top. This famous outfit was known for speed in its midcentury heyday, and was located near Peña’s father’s shop in Santa Fe Springs. The opposing forces of assimilation and tradition create a central tension in Peña’s work. Growing up, his father embraced the Americanness of hot rods and sports teams, while his mother sought to strengthen the family’s Mexican roots. Works often incorporate elements that nod to both points of view. “The Bear Will Take Care of You” imagines a fantastical auto body shop, with the famous happy bear sign welcoming the viewer into the space and collaged pictures of vintage cars along the bottom edge. Each of Peña’s works contains some element of metal support, an ode to his father’s work as a machinist. Here Peña transforms the striped fabric of a typical mechanic’s shirt into a collage element, where it becomes an underlying overall pattern. Roses and text from a Mexican bakery bag dot the composition, undermining the machismo of the mechanic’s gear. Pulled between two poles and left feeling out of place in both worlds, Peña developed a fascination with Americanness as a concept and an identity, one he aims to tease apart in his work. These images and compositions all intimately connect to his working-class background and offer a compelling glimpse into his unique experience in Southern California, specifically South East Los Angeles. Peña’s work pieces together hallmarks of Americana and the Mexican American experience to create a visual conversation grounded in delicate symbols and memory objects that further bridges the gap between street aesthetics and studio practices.

* Rasquachismo is a theory developed by Chicano scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto to describe “an underdog perspective, a view from “los de abajo” (from below) in working class Chicano communities which uses elements of “hybridization, juxtaposition, and integration” as a means of empowerment and resistance. The term is commonly used to describe aesthetics present in the working class Chicano art and Mexican art movements which “make the most from the least.”

Photo: Jerry Peña, From North to South & East to West, 2024, Acrylic Paint, Enamel paint, Sheet Metal, 35mm Photograph print Automotive Windshield, Found Objects, Collage, Clear Gloss, Mechanic Shirt, mounted on wood panel, 60 x 60 x 2 inches, © Jerry Peña, Courtesy the artist and Charlie James Gallery

Info: Charlie James Gallery, 961 Chung King Road, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 1/6-6/7/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-17:00,, https://www.cjamesgallery.com/

Right: Jerry Peña, Fueled By Coors, 2024, Acrylic Paint, Enamel Paint, Found objects, Collage, Sheet Metal, Clear Coat, mounted on wood panel 28.5 x 32.75 x 2 inches, © Jerry Peña, Courtesy the artist and Charlie James Gallery

Right: Jerry Peña, Somos del barrio angelino, 2023, , Soccer jersey, Automotive windshield, clear coat, 30 x 33 x 1.25 inches, © Jerry Peña, Courtesy the artist and Charlie James Gallery

Right: Jerry Peña, Thank You Windshield, Thank You Dashboard III, 2024, Acrylic Paint, Collage, Photograph Print, Automotive Windshield, Clear Gloss Coat, mounted on wood panel, 16 x 17 x 2 inches, © Jerry Peña, Courtesy the artist and Charlie James Gallery