TRIBUTE: Olafur Eliasson-Your Curious Journey

The works of Olafur Eliasson explore the relevance of art in the world at large. Olafur Eliasson uses his works, which encompass painting, photography, sculpture and large installations, to inquire into the relationships between the real and the artificial, perception and experience. His work stands out for putting viewers at the core, allowing them to delve into many of the challenges facing our society, and offering them different experiences which entail, in Eliasson’s words “taking part in the world.”

The works of Olafur Eliasson explore the relevance of art in the world at large. Olafur Eliasson uses his works, which encompass painting, photography, sculpture and large installations, to inquire into the relationships between the real and the artificial, perception and experience. His work stands out for putting viewers at the core, allowing them to delve into many of the challenges facing our society, and offering them different experiences which entail, in Eliasson’s words “taking part in the world.”

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Singapore Art Museum (SAM) Archive

Featuring 17 artworks that employ diverse media to reflect the expanse of Olafur Eliasson’s wide-ranging oeuvre, “Your Curious Journey” the first major solo exhibition in Southeast Asia presents major themes of his three-decade-long practice (embodiment, experience, perception), as well as the urgency of climate action and more-than-human perspectives. Included in this exhibition are also never-before-seen works. “The glacier melt series” (1999/2019) is a series of aerial photographs that documents 30 glaciers in Iceland. The prints are presented in pairs. In each pair, the image on the left portrays a glacier in 1999, and the image on the right shows the same glacier 20 years later. In every pair, the ice sheets have clearly receded over time to reveal more of the rocky and mossy earth beneath. Though Eliasson did not set out to make a work on climate change when he first photographed the glaciers in 1999, he was cognisant of the landscape’s vulnerability. By comparing the same glaciers in 1999 and 2019, the work corroborates how these primordial environments have and continue to be shaped by human activity. In “Ventilator” (1997), a lone electric fan hangs from the ceiling. The fan pushes air out as its blades turn and the air reciprocally propels the fan in the opposite direction. This oscillatory cycle continues as the electric fan whizzes tirelessly within the gallery. Though the fan’s movement is constant, its swing pattern is erratic and unpredictable. A simple contraption composed of no more than three components, “Ventilator” is a playful study of how we can be made to perceive invisible elements such as air. Whilst steady streams of wind often serve the practical function of cooling us down, the fan in “Ventilator” circulates air without objective, rendering a utilitarian object effectively rudderless. “Multiple shadow house” (2010) comprises a series of free-standing rooms that are lit in multiple shades of colours such as blue, purple, yellow and green. When we enter these rooms, our shapes are cast as an array of glitched shadows onto translucent projection screens. This effect encourages us to try out various dramatic movements to produce a range of effects: walking back and forth, moving closer to the screen or interacting with fellow visitors. As the silhouettes are visible from both inside and outside these rooms, the work can be thought of as a life-sized stage for shadow play, on which we perform alone but also together with others. Carved out of driftwood found on the coast of Iceland, “Adrift compass” (2019_ is a log that has been sharpened on one end and painted with a compass rose. Commonly found on maps or nautical charts, compass roses help users find their bearings by pointing out cardinal directions. Mirroring this function, strong rare-earth magnets are suspended beneath the sculpture, ensuring that it is always aligned along a north-south axis. Since 2009, Eliasson has combined found objects such as rocks, pieces of glass and wire with magnets. His fascination with compasses stems from their ability to provide a clear sense of place and direction.

“Double spiral” (2001) takes the form of a single steel tube rolled into a double helix. The sculpture is motorised and, when activated, half of the spiral inches upwards while the other half slowly descends. Despite the impression of movement, the sculpture’s actual position does not shift. At eye level, the sculpture’s double-helix form is distinct and reminiscent of the organic structure of DNA. Yet, the sculpture casts a very different shadow on the ground, one of concentric circles that overlap one another like the moving cogs of a clock. Located squarely within Eliasson’s relationship with Iceland is “Moss wall” (1994). An organic, vertical carpet, this work comprises reindeer cup lichen (Cladonia rangiferina), also known colloquially as “reindeer moss,” which is a symbiont of at least one fungus and one alga and covers immense areas in northern tundra and taiga ecosystems. Here, the lichen is woven into a wire mesh to blanket an entire gallery wall. Disrupting an otherwise homogenous museum space, it collapses the boundaries between interior and exterior, bringing one of nature’s great wonders directly to the audience as they come face-to-face with a living and breathing wall. The susceptibility of grandiose glaciers to climate fluctuations is emphasised in “The last seven days of glacial ice” (2024). A single ice block, originally found on Diamond Beach in the south of Iceland, was visualised in its various stages of melting. Each stage, cast in bronze, evokes a semblance of permanence. Every cast is paired with a clear orb of glass—a volumetric representation of the water that is lost. As an exercise that may be described as elegiac data visualisation, “The last seven days of glacial ice” prompts us to consider the steady process of degradation, and the sum total of what is lost in the process. Drawing machines feature prominently in Eliasson’s practice, including the series “The seismographic testimony of distance (Berlin–Singapore, no. 1 to no. 6)” (2024). Despite incurring higher levels of carbon emissions, goods are often transported by air for expedience, and artworks are no exception. Mindful of the exhibition’s carbon footprint, the artist chose to ship most of the artworks shown in the exhibition to Singapore by sea instead. To document their journey across land and sea, six rudimentary drawing machines were included in the shipment. Set up over blank paper sheets, ballpoint pens were attached to each mechanical arm and allowed to run free, marking every bump and turn the crates took, resulting in a series of unique seismographic sketches.

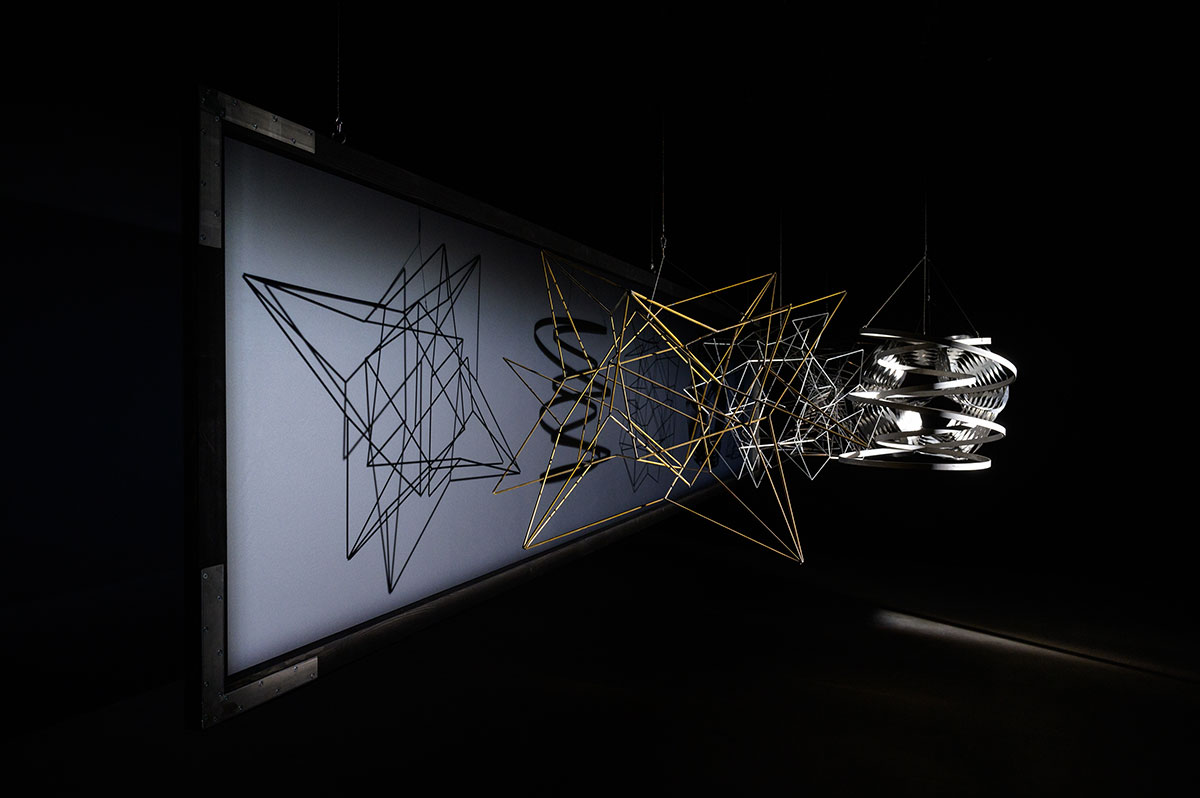

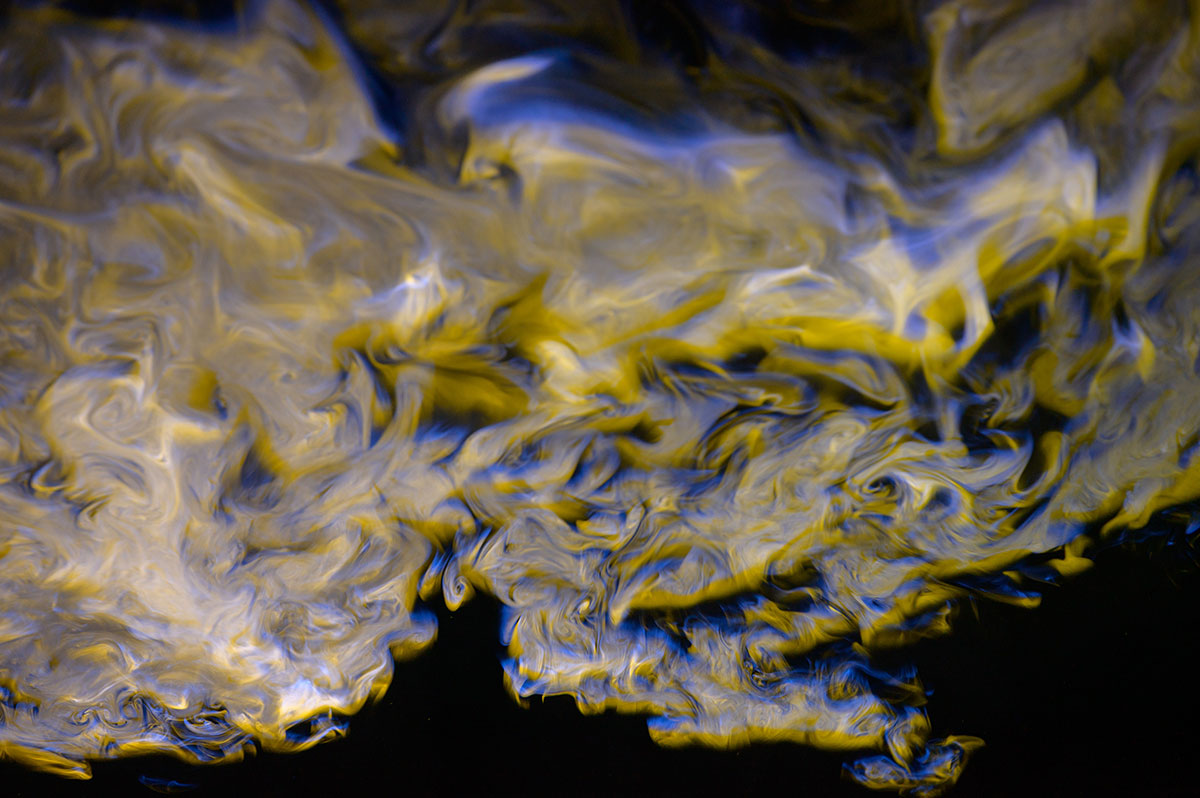

In “Beauty” (1993), a fine sheet of mist, reminiscent of a light drizzle, is illuminated by a singular spotlight in a darkened space. When viewed at just the right angle, a prismatic reflection of light reveals itself—a luminous rainbow that illustrates its namesake: beauty. Eliasson leaves “Beauty’s” mechanisms in full view, a simple combination of a spotlight, a punctured hose and us, the viewers, paring the rainbow down to its most essential constituents and demonstrating his continued interest in the formation of natural phenomena. Though the water is constantly flowing, the appearance of this apparition varies depending on our position relative to the artwork. As light is refracted and reflected on the water droplets differently, no two viewers see the same rainbow. The subject of “Beauty” is thus both the light and the viewer, which begs the question: Does the rainbow exist independently, or does it exist because we perceive it? This reflexivity that “Beauty” facilitates, combined with the exposed apparatus of the work, heightens our awareness of the very act of perception and our experience of seeing. Walking into the installation space of “Life is lived along lines” (2009), we first encounter the rear face of a projection screen with shadows cast upon it along a horizontal line. These shadows hint at what lies behind. Laying bare his methods of production, Eliasson allows us to walk around the screen to discover the apparatus that flattens three-dimensional forms into two-dimensional outlines, five object models, a set of blinds and a spotlight. As the object models rotate slowly along a central axis, their shadows follow suit. This shared movement creates synchronicity between the image and the object, reminding us that they are but two sides of the same coin. In “Circumstellar resonator” (2018), light is passed through a prismatic lenticular surface, before splitting into multiple rings that radiate from a central point. It draws upon the principles of a Fresnel lens, a piece of glass that captures peripheral beams from a single source to produce an intensified beam of light. Fresnel lenses were used in lighthouses to transmit light to ships farther out in the open sea and guide them to safe harbour. :Circumstellar resonator/s” bands of light are a different kind of beacon, extending the scientific properties of this invention beyond practical applications and tuning them towards an aesthetic experience. “Object defined by activity (then)” (2009) consists of a water feature housed in a pitch-dark room. Its exuberant bursts of water are lit solely by a strobe light, which flickers ceaselessly at an aggressive tempo. Illuminated each time for a mere fraction of a second, we are barely able to register each fugitive image of the water’s mesmerising, organic and ever-changing form. While the consistent, uninterrupted sound of running water grounds us in real time, the work’s speed, high-key lighting and relentless, stroboscopic siege of spectacular imagery fragments and freezes this ongoing process into a multitude of micro-fissures in time. At once a dynamic physical installation and a series of still, fleeting frames, “Object defined by activity (then)” is perceived as simultaneously kinetic and static. In “Symbiotic seeing” (2020), the ceiling of a room seems to inhabit three states of matter at once. At first glance, it may appear flat and solid. Yet, upon closer inspection, this ceiling looks like a layer of liquid skin, with tiny swirling and eddying ripples. These effects are the result of coloured laser lights coalescing with periodically released fog. By incorporating ephemeral materials, Symbiotic seeing appears to occupy a liminal space between physical states and becomes an organic environment for contemplative movement that unfolds both personally and communally.

Photo: Installation view of Olafur Eliasson’s ‘Wind writings (22 March 2023, 23 March 2023, 20 June 2023, 28 June 2023)’ & ‘Sun drawing (21 June 2023, 22 June 2023’ (2023), as part of ‘Olafur Eliasson: Your curious journey’ at SAM at Tanjong Pagar Distripark; Photo: Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures; Image courtesy of the artist and Singapore Art Museum; © 2023 Olafur Eliasson

Info: Singapore Art Museum,39 Keppel Rd, #01-02 Tanjong Pagar Distripark, Singapore, Duration: 10/5-22/9/224, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-19:00, www.singaporeartmuseum.sg/