PRESENTATION: And Yesterday And Tomorrow

Through its recurrent “HERE AND NOW” series, the Museum Ludwig questions conventional ways of exhibition-making and examines its own work as an institution. The tenth project in the series TITLED “And Yesterday and Tomorrow”, brings together selected contemporary and historical artworks with scientific material to explore our experiences of time and the places we occupy. Moreover, by including various disciplines, the exhibition provides a space for collective learning. This is also the Museum Ludwig’s first demonstrably climate-neutral show.

Through its recurrent “HERE AND NOW” series, the Museum Ludwig questions conventional ways of exhibition-making and examines its own work as an institution. The tenth project in the series TITLED “And Yesterday and Tomorrow”, brings together selected contemporary and historical artworks with scientific material to explore our experiences of time and the places we occupy. Moreover, by including various disciplines, the exhibition provides a space for collective learning. This is also the Museum Ludwig’s first demonstrably climate-neutral show.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museum Ludwig Archive

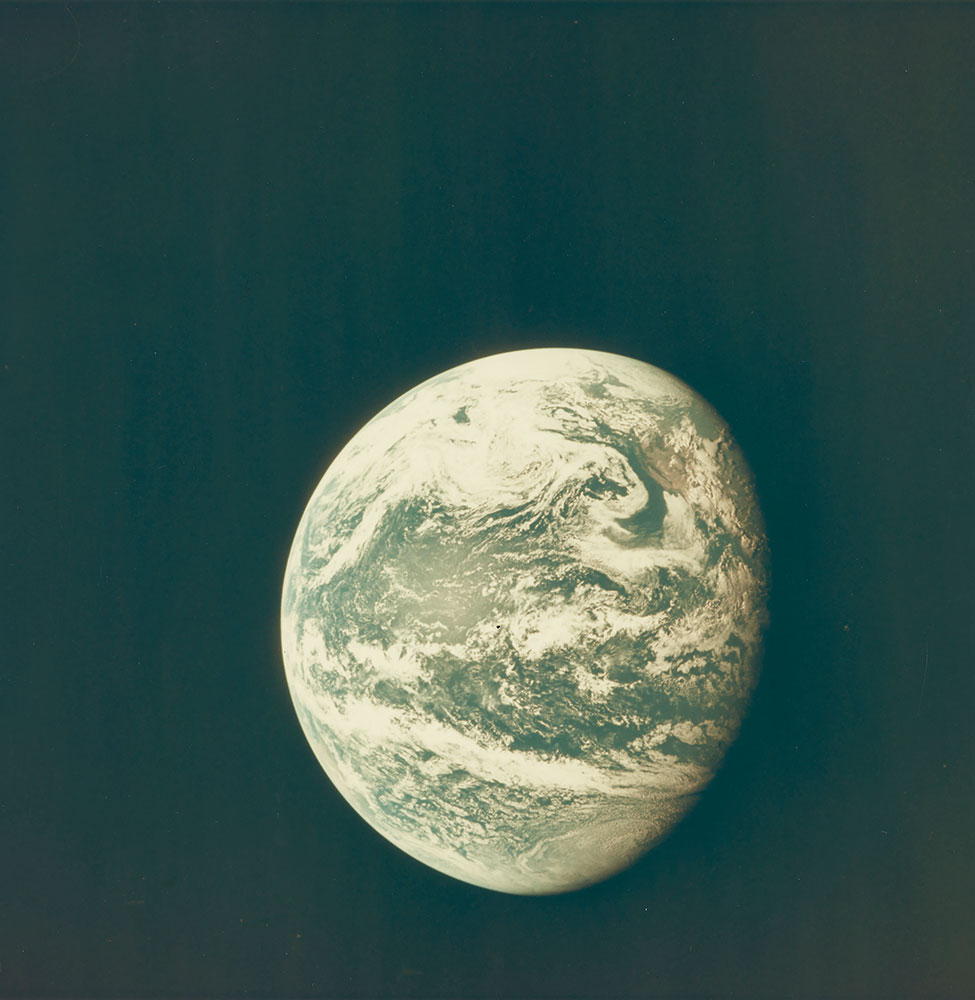

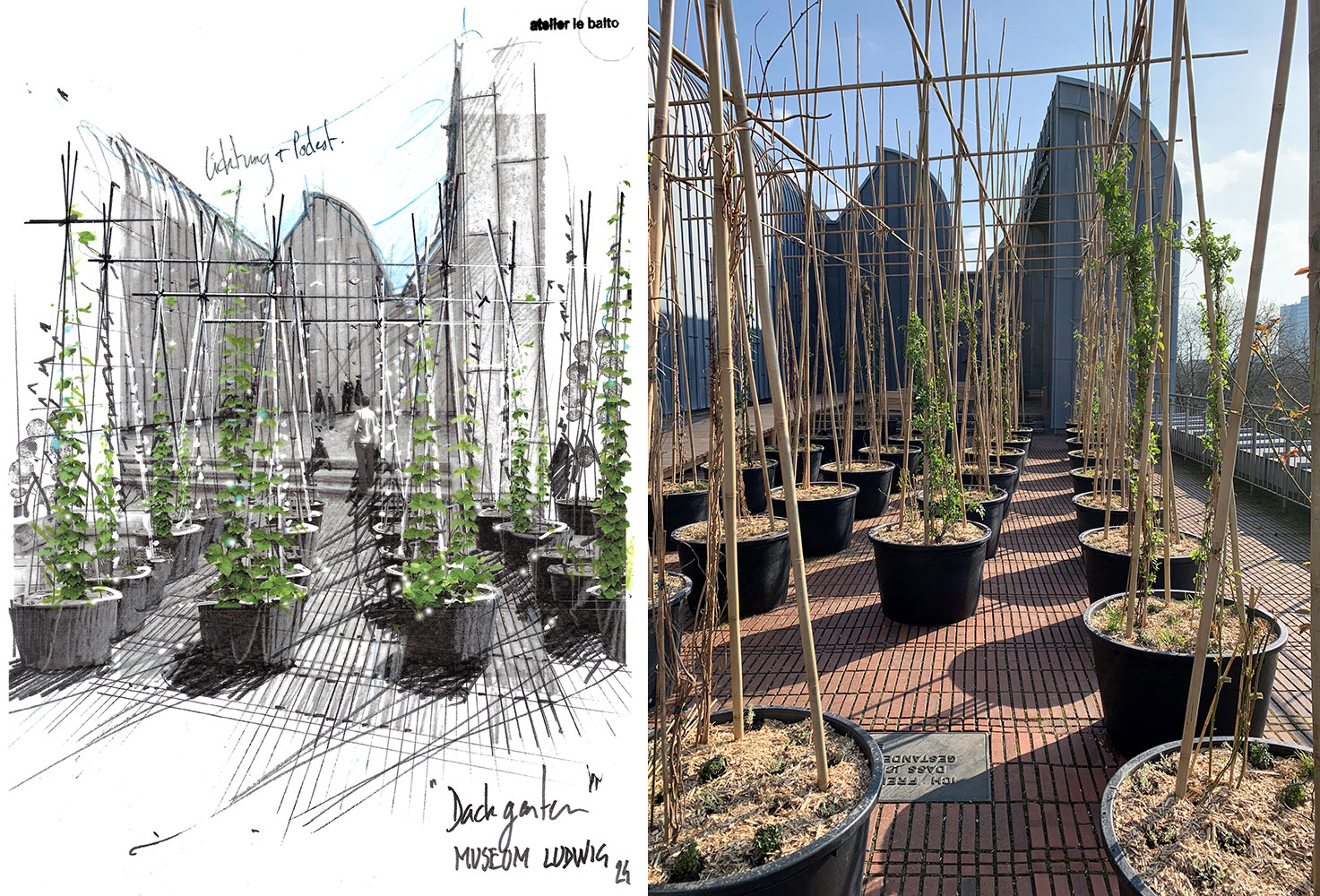

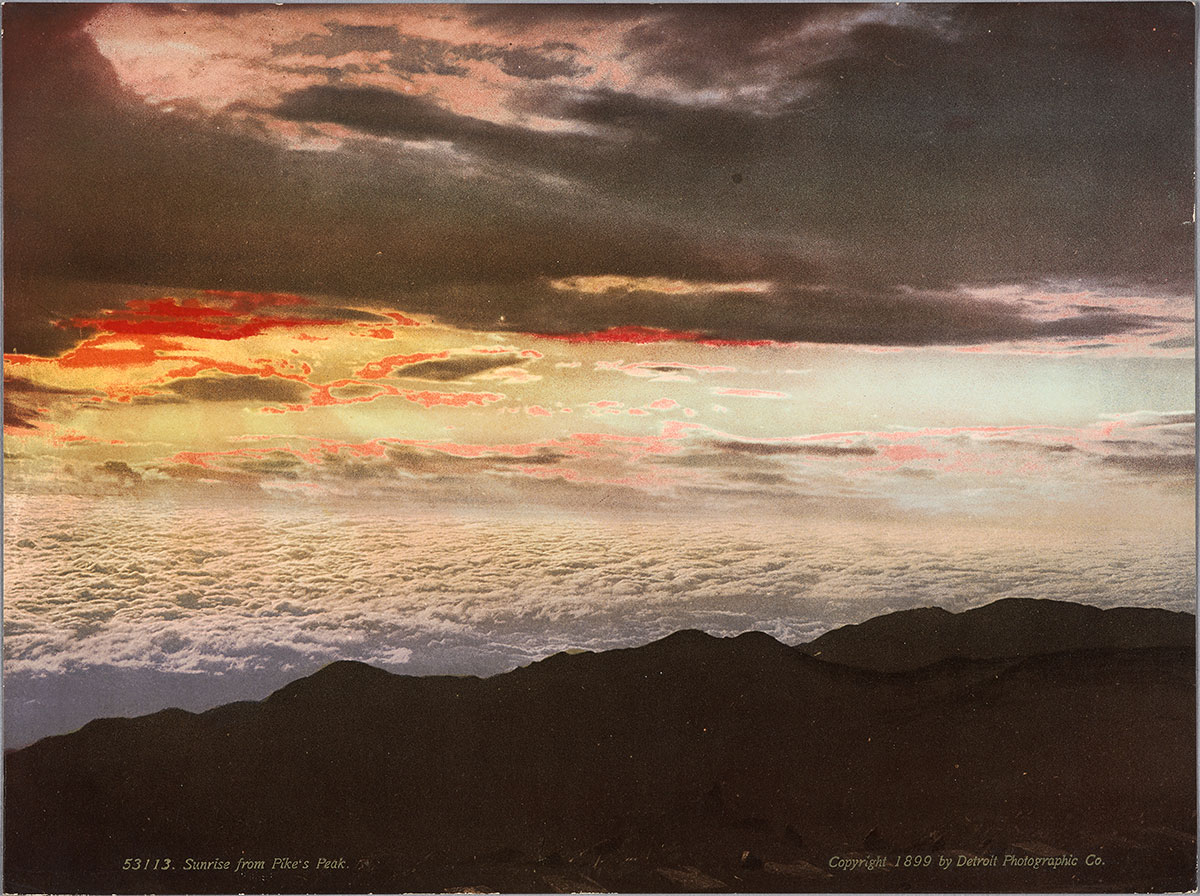

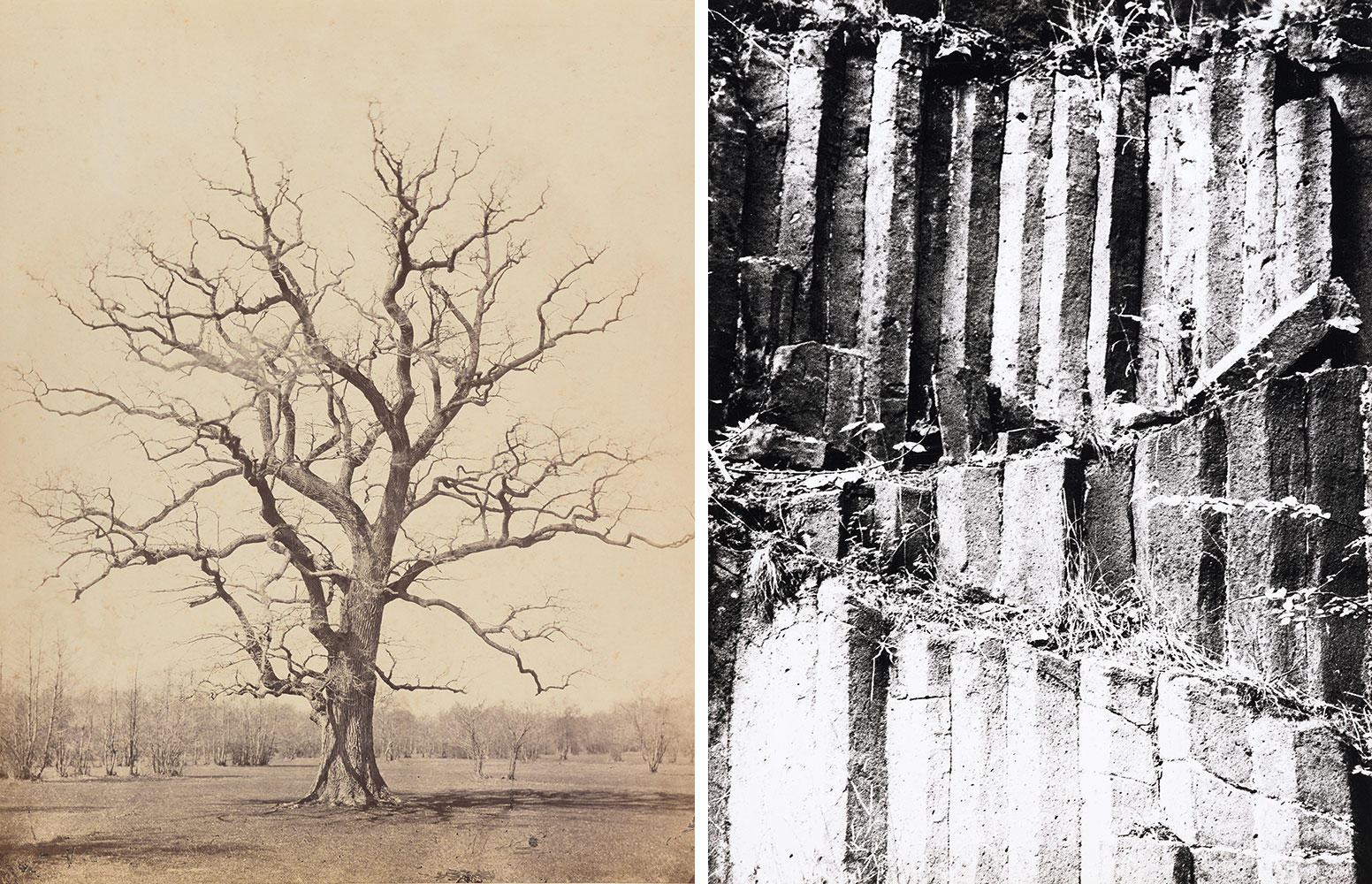

Using a focused selection of works, materials, and texts, the series of the exhibition “here and now” is related to yesterday and tomorrow. To experience “here,” we turn our gaze to the ground on which the museum stands. What does the soil under our feet reveal? How is “here” even defined when the tectonic plates we stand on move almost as fast as our fingernails grow? In 1959, Chargesheimer photographed workers in a basalt quarry in the Siebengebirge. He published one of the pictures in his photo book “Menschen am Rhein” (People on the Rhine) in 1960. The late prints of basalt shown here deliberately leave out the people. The stone thus appears to us as untouched by the Anthropocene. Basalt and the formation of the world were the subject of the “Basalt Controversy” at the end of the 18th century: were the earth and the most widespread rock on it, namely basalt, formed by deposits in the sea or by volcanic eruptions? Today, one assumes a rock cycle of 200 million years. Basalt weathers over time, is gradually eroded, and finally settles again. When its sediment gets deeper into the earth’s crust, it is pressed there, then liquefied as magma in the earth’s interior, and returns to the earth’s surface as lava. Here it hardens into formations such as those photographed by Chargesheimer in 1959. Gerhard Richter’s paintings of the Alps as reminders of the continual fluctuations of the earth’s surface and human existence. Alpine and mountain landscapes appear repeatedly in Gerhard Richter’s work between 1965 and 1970. These screen prints are based on paintings of the same size and are part of a series of five depictions of the Alps. However, one searches in vain for a horizon line characteristic of mountain views. Instead, our gaze is directed toward areas of light and shadow that push against each other and are reminiscent of the force with which the Alps arch upwards as the Eurasian tectonic plate collides with the African plate. Tacita Dean’s impressive work “Sakura (Taki I)”, the image of a thousand-year-old cherry tree whose supported branches are in bloom, visualizes the ephemerality of our personal present. In 1922, this cherry tree in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, which is over a thousand years old, was declared a national treasure. One hundred years later, in March 2022, the artist Tacita Dean visited it during the cherry blossom season. Thanks to good care, it survived earthquakes, heavy snow, and nuclear disaster. Its age and durability contrast with the fleeting beauty of the cherry blossoms. “Sakura (Taki I)” is part of a series of trees whose photographs Tacita Dean has worked on, making them even more present as individuals in an almost magical way. In 1962, Alfred Ehrhardt traveled to Iceland for a second time to take photographs and make film recordings. He had already been there in 1938, photographing volcanoes, springs, and glaciers. He believed that in Iceland he could get closer to the “elemental formations of the primordial forces.” In Iceland it is indeed possible to observe how the Eurasian and American plates are drifting away from each other. The resulting Silfra fissure, which lies in volcanic basalt rock, widens by around seven millimeters every year. Such forces inside the earth also shaped the environment of Lake Myvatn, which is only 2500 years old. Historical photographs of impressive cloud formations by Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, and Alfred Stieglitz. Gustave Le Gray was the first to succeed in depicting clouds clearly in landscape photographs. Until then, the sky appeared bright and cloudless in photographs, which was due to the fact that the negative plates reacted particularly strongly to the color blue and the sky quickly overexposed. The sea and landscape, on the other hand, were easily recognizable. Clouds were therefore often retouched into the picture afterwards. However, since Le Gray considered clouds to be an important element of his seascapes, he photographed the sky and earth separately-the sky briefly, the sea longer-and then superimposed them. Some cloudy skies are therefore repeated in his work. Later, in the 1870s, meteorologists began to use photographs of clouds to classify them. They wanted to know, for example, whether clouds were similar all over the world. Thanks in part to photography, it was concluded that they are. In the 1870s, regional weather observatories in Germany also published weather forecasts for the first time. In the 1850s, Charles Marville repeatedly photographed the cloudy skies over Paris from his Paris apartment. Later, in the 1870s, meteorologists began to use photographs of clouds to classify them. They wanted to know, for example, whether clouds were similar all over the world. Thanks in part to photography, it was concluded that they are. In the 1870s, regional weather observatories in Germany also published weather forecasts for the first time. Alfred Stieglitz left behind around 400 cloud photographs. In some of them, he focused on the emergence of aviation. In others, he sought in the clouds the outer image of an inner state and therefore called them “equivalents. ” The cumulus cloud visible in the photograph looks almost threatening. Clouds are differentiated according to the height at which they are located. It may have extended over the two lowest cloud levels, if not all three, and would therefore probably have been accompanied by showers. These photographs are shown alongside sketches for a new planting scheme developed by landscape architects atelier le balto especially for the roof terrace of the Museum Ludwig. With that the Museum Ludwig is responding to the Bischofsgarten, an tenth-century garden once located on the present site of the museum. The exhibition “And Yesterday and Tomorrow” traverses both the inside of the museum and its environs, where visitors can sit in the new garden while watching the clouds pass by. During its seven-month run, the exhibition will be periodically reconfigured, with individual works changed to create new ensembles. This transformation will be accompanied by Yoko Ono’s song “I Love You Earth”, in which the artist addresses our planet with the line, “You are our turning point in eternity”. And Yesterday and Tomorrow juxtaposes contemporary works with historical works and actual landscape architecture while scientific fields such as geology, dendrology, and archaeology play a visible role. A comprehensive accompanying program also provides learning opportunities through exchange forums, group activities, educational workshops, and much more.

Participating Artists: atelier le balto, Chargesheimer, Tacita Dean, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Yoko Ono, Gerhard Richter, Alfred Stieglitz

Photo: Tacita Dean, Sakura (Taki/), 2022, Colored pencil on Fuji Velvet paper mounted on paper, 348 x 500 cm, Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery New York/Paris/Los Angeles, and Frith Street Gallery, London, © Tacita Dean

Info: Curator: Miriam Szwast, Museum Ludwig, Heinrich-Böll-Platz, Cologne, Germany, Duration: 9/3-13/10/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.museum-ludwig.de/

![Gerhard Richter, Schweizer A/pen, [Swiss Alps], 1969, Al from the five part set of prints Schweizer A/pen, [Swiss Alps], screenprint on lightweight card, 69,5 x 69,5 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Gerhard Richter 2024 (15022024) Repro: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/02-9.jpg)

Right: atelier le balto, Museum Ludwig roof garden, © atelier le balto, Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne/Marc Weber

Right: Chargesheimer, Basalt, 1969/1970, Gelatine silver paper, 39,7 x 29,8 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Repro: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne