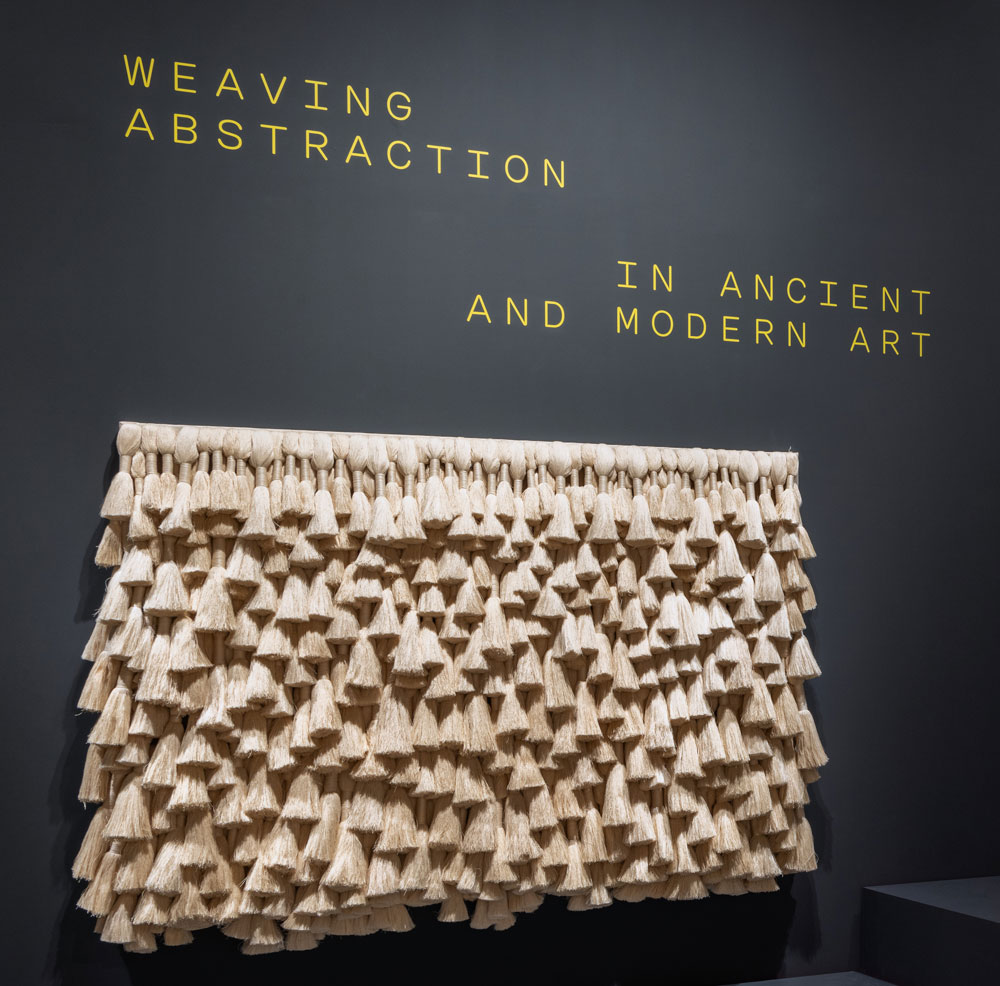

TRIBUTE:Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art

The process of creating textiles has long been a springboard for artistic invention. In the exhibition “Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art”, two bodies of work separated by at least 500 years are brought together to explore the striking connections between artists of the ancient Andes and those of the 20th century.

The process of creating textiles has long been a springboard for artistic invention. In the exhibition “Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art”, two bodies of work separated by at least 500 years are brought together to explore the striking connections between artists of the ancient Andes and those of the 20th century.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Met Archive

The exhibition “Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art”, features textiles by four distinguished modern practitioners (Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney, and Olga de Amaral) alongside pieces by Andean artists from the first millennium BCE to the 16th century, who, though their names are largely unknown to us, created works of exceptional technical and formal refinement. This cross-historical exhibition offers new insights into the emergence of abstract imagery. The constructive nature of weavings, arising from the grid formed by crossing the warp and the weft (the vertical and horizontal elements of the loom), prompted the formal investigation of a geometric iconography that emphasizes the integral relationship between structure and design in textiles, forging distinctive paths to abstraction in both historical periods. Weaving is one of the oldest and most complex art forms in the world, with a rich history beginning 10,000 years ago. Textiles in the ancient Andes were also fundamental to the exchange of information in the pre-Hispanic period, used to swiftly transmit social and political messages in a manner that overcame linguistic and geographic barriers. Artists of early European modernism and the Fiber arts movement* sought to uplift and recenter the medium, commonly relegated to the realm of “women’s work.” Each of the four modern artists featured in the exhibition developed innovative approaches to an ancient medium through deep study of Andean techniques. Within this legacy, they responded to the demands and challenges of the modern industrial society while maintaining a firm commitment to abstraction as the language of modernity. Shown together in this exhibition, these ancient and modern weavings reposition the place of textiles in global art history.

Sheila Hicks’s distinct approach to the constructive methods of ancient Andean textiles was ultimately expressed in her “open compositions.” She did not employ weaving techniques per se to create these works but, rather, referred to a pre-Hispanic tie- or resist-dying technique still employed across Latin America where threads are wrapped to prevent them from absorbing dye. In “The Principal Wife”, Sheila Hicks inverts this process by leaving the unwrapped sections undyed. The work “Untitled” (1986) exemplifies the way Hicks likes to describe weaving as “the voyage of the line.” In what seems an unorthodox weaving practice, here she decided to allow the warp threads to simply hang vertically, uninterrupted by weft threads, creating slits that allow light to filter through. This technique echoes what she sees as an ancient system to codify signs. Hicks first employed the technique in 1961. The work “Linen Lean-To” (designed 1967–68; executed 1985) relates to a commission. In 1968, Hicks collaborated with the American interior designer Warren Platner on a room at the George Jensen Center for Advanced Design in New York. Two walls of wet-spun, spirally wrapped linen tassels contributed to a cohesive environment of natural colors and organic materials that included furniture designed by Hans Wegner. In her collaborations with architects, designers, and fabric manufacturers, Hicks emphasized the tactile and material qualities of fiber works as defining aspects of modern interiors.

Lenore Tawney began to use the Peruvian openwork technique of gauze in 1955. In 1961, she studied gauze-weave techniques with the American fiber artist Lili Blumenau and made delicate works such as this one emulating the fine openweave textiles of coastal Peru. The early sixties marked the artist’s jump from more classical forms of tapestry to radical innovations with the grid-based principles of weaving as she turned the structural aspects of the medium into its primary visual elements. “Peruvian” (1962) pays homage to the checkerboard pattern found in ancient Andean textiles, particularly Inca tunics. This piece is constructed as a tubular weave, a technique that shares the same structural principle as the double weave. In both methods, two layers of cloth are woven separately, though in one weaving operation; however, in tubular weaves, there is no exchange of the two layers. Instead, a continuous weft thread alternatively weaves both layers in aspiral movement, closing both selvages and thus forming a tube. Tubular weave was also practiced in ancient Peru.

Prewoven elements allowed Olga De Amaral to enter a dialogue with architecture, as demonstrated in “Woven Gridded Wall #66” (1970). Made with heavy fibers such as coarse wool and horsehair, the interlaced elements use frame braiding on a large scale. Ancient Andean architecture and textiles influenced De Amaral deeply. In 1969, she visited Peru, where she was overwhelmed by “the ancestral intelligence” and “high mathematics—present in everything textile in ancient Andean culture”. Vertical openings created with the open-warp technique of slits activate “Shrouded River” (1966). Tawney enjoyed placing works like this one away from the wall to allow light and air to filter through. Transparency was one of Anni Albers’s key aspirations for the medium, and her 1965 book On Weaving included an illustration of “Tawney’s Dark River” (1962), a similar woven form with slits. Shrouded River’s elongated form is meant to reference the shape of a river or the trace left by a boat in the sea. The title also alludes to the tradition of wrapping ancestral bundles in fine cloth. In 1972, De Amaral devised her signature tile tapestries. Defined by the artist as her “words,” the tiles are rectangular woven units of linen and cotton sewed to an underlying strip. “Alchemy 13” (1984) shows the modular rigor of this technique, which recalls tile roofs or complex layered systems like a bird’s plumage. Its surface shines with the iridescent effects of gold leaf, a material the artist began using in 1973 to turn textiles into “golden surfaces of light.” She devised her Alchemies series “in homage to a pre-Columbian gold mantle I had the fortune of seeing in Peru’s Gold Museum.”

Anni Albers admired Andean weavers’ mastery of multiply structures, such as double, triple, quadruple and tubular weaves. In her own work, she paired a geometrically abstract vocabulary with constructive processes like double and triple weaves. Double weaves present two separate layers, which can be locked at both sides, at one side, or within the fabric, wherever the design asks for an exchange of top and bottom layers (usually of different colors). Albers explained that the purpose of these ancient double- and multi-ply weaves was an aesthetic one: “They were to make possible designs of solid colored areas within other contrasting solid colored areas”. Albers probably studied the technical analyses of the various types of openwork provided by Raoul d’Harcourt in his 1934 book “Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques”, whose French first edition she owned. Besides wall coverings and drapery, she designed textiles that could function as room dividers. In these works, she played with the ability of open weaves to modulate space and light. Furthering the relationship of weaving to architecture, these “partition materials,” as she called her screens, were intrinsic to her vision for modern living environments. She also enjoyed introducing new materials, such as cellophane. “Wallhanging” (1924) is one of the first pieces that Albers made at the Bauhaus. It exemplifies the “quintessence of weaving” with its simple, single-weave structure. A weaving, in its essence, is defined by the intersection of one system of threads—the warp—with another—the weft—at right angles to form a grid structure. In weaving’s reticular interlacing, the artist found her own pathway to abstraction. She succeeded in converting the medium into a model for the geometric style that came to define the interwar period.

* From the early 1960s to the late ’70s, in a chapter of art history known as the fiber art movement, artists, predominantly women, across Europe and the United States began experimenting with thread and fabric, often pushing them into three dimensions and away from the wall.

Photo: Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, on view March 5 – June 16, 2024. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Hyla Skopitz

Info: Curators: Iria Candela and Joanne Pillsbury, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Met Fifth Avenue, 82nd Street, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 5/3-16/6/2024, Days & Hours: Mon-Tue, Thu & Sun 10:00-17:00, Fri-Sat 10:00-21:00, www.metmuseum.org/

Right: Olga de Amaral, Alquimia 13, 1984, Linen, rice paper, gesso, indigo red and gold leaf, 72 × 62 in. (182.9 × 157.5 cm), Gift of Olga and Jim de Amaral, 1987, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1987.387) Image: © Courtesy Olga de Amaral. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo by Peter Zeray

Right: Sheila Hicks, Rallo, 1957, Wool, 9 1/2 × 5 1/8 inches (24.1 × 13 cm) Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Image: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution

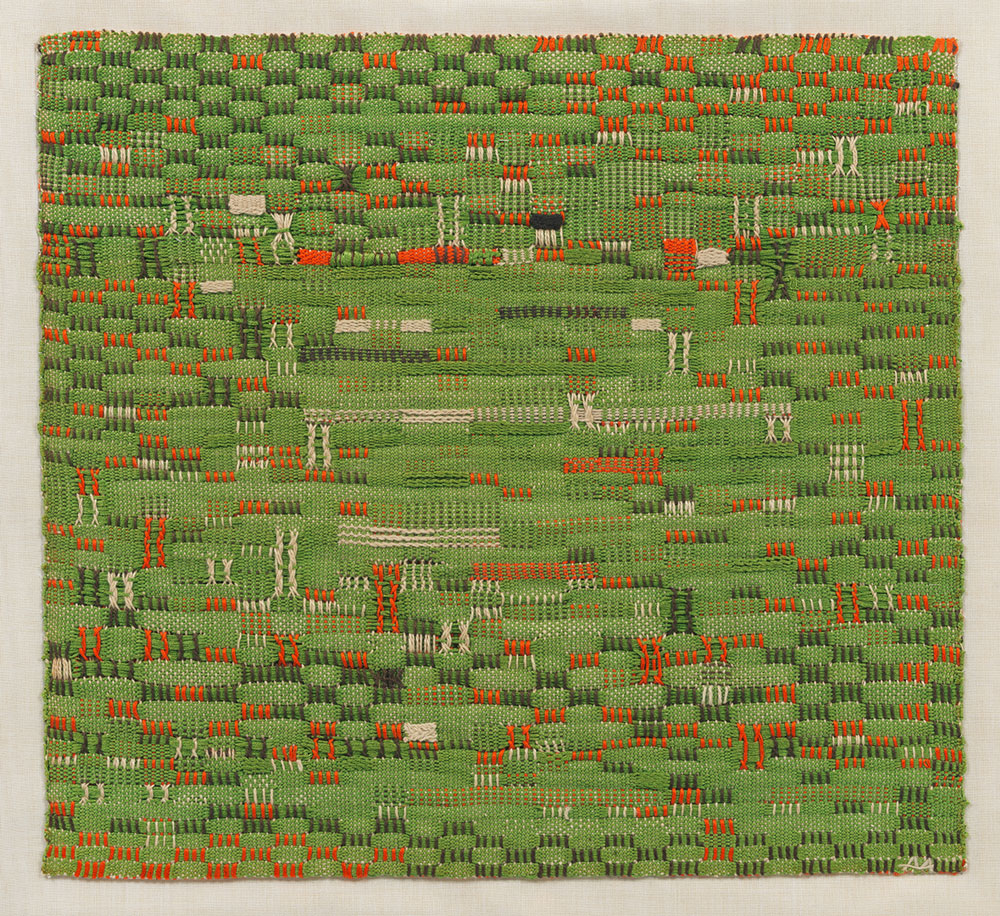

Right: Anni Albers, Red Meander, 1954, Linen and cotton, 20 1/2 × 14 3/4 in. (52.1 × 37.5 cm) Private Collection, Image: © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2024 Photo: Albers Foundation/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art. Albers, Anni (1899-1994)