ART CITIES: Vienna-The Beauty of Diversity

The exhibition “The Beauty of Diversity” manifests its dynamic nature in the juxtaposition of renowned artists who constantly attempted to break out of the canon yet became canonized themselves with new discoveries as well as with those who disrupt accustomed ways of seeing, swim against the current, shake the foundations of high culture, violate norms, and thereby lay the foundation for an aesthetics of the diverse.

The exhibition “The Beauty of Diversity” manifests its dynamic nature in the juxtaposition of renowned artists who constantly attempted to break out of the canon yet became canonized themselves with new discoveries as well as with those who disrupt accustomed ways of seeing, swim against the current, shake the foundations of high culture, violate norms, and thereby lay the foundation for an aesthetics of the diverse.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Albertina Modern Archive

The exhibition “The Beauty of Diversity” develops an aesthetics of the diverse that upends the ideality of classicist stylistic and formal strivings and pursues the beauty to be found in the grotesque, impure, and repressed while lending visibility to that which exists on the fringes and diverges from the norm. The hybrid mixing and recombination of distinct systems and genders plays as prominent a role here as does the presentation of the marginalized. Artists from the continents of Australia, Africa, Asia, and South America feature prominently in this presentation and serve to undermine Eurocentric thought and action and/or Western art and culture. Autodidacts exhibit a pronounced will to do what one must, proving their authenticity by assertively acting upon art’s internal necessity—just as individuals who probe and transcend boundaries not only call to mind art’s role as an anthropological constant but also, in their deviant modes of existence, exemplify nonconformist strategies by which to live and work. The exhibition is divited in thematic rooms. Puppet Shows: Puppets made of soft fabrics and materials for modeling and children’s play like clay and plasticine evoke the secure, cared-for, and protected realm of childhood, an idyllic world. But as the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud once set forth, the distance between the security and coziness of the nursery and the horror of the uncanny is a short one. Among those artworks that address the idea of reality crashing in upon a prelapsarian world are creations that flirt with the aesthetics of puppetry or even seem deceptively puppet-like. They show just how closely guilt and innocence, power and powerlessness, privilege and subjection to discrimination often coexist. Stefanie Erjautz’s early puppets seem as if taken from a fantastical world. In later works, however, she began orienting herself on newspaper photographs and developed an interest in social themes, addressing abuse and violence in religion, the church, and (geo)politics. From portraying the dictator Adolf Hitler to paying homage to the artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei, her oeuvre engages with human beings’ entire behavioral range. It is the inexpressible, on the other hand, that is lent expression by Tony Oursler’s distorted faces and emotionally intense projections of protagonists trapped in dialogic loops onto often puppet-like artificial bodies and frames. Self-Empowerment: The right to self-determination is an important demand of the feminist movement, strategies of self-empowerment have always existed in art. Indeed, one of its functions has been as an organ of (identitarian) political expression, a bullhorn for activists demanding the improvement of conditions faced by groups with shared interests and experiences of discrimination. Particularly the idea of women’s empowerment, as an aspect of the feminist avant-garde since the 1970s and a reaction to discrimination against women, has retained its great importance to this day. Artists have pioneered the promotion of women’s rights, using powerful imagery to rebel against the status quo and fighting to both alter social structures and ameliorate onerous conditions. They self-confidently demonstrate what Austrian art’s grande dame Maria Lassnig, striding across New York as a “Queen Kong” of sorts, termed Woman Power. Common to Lassnig and the artist Miriam Cahn is their aversion to being understood as explicit feminists amidst careers consistently oriented toward the attainment of acceptance and recognition throughout the art world.

Art Brut: There exists a need to question the belief that art can permit inferences concerning the psychological dispositions of its creators and that visual images say something about the health or even illness of those who produce them. Assuming all-too-close associations between biography, artist, and work is problematic in numerous respects. The 20th century witnessed the development of various tendencies that interwove art and the psyche, discovering the unconscious mind as a source of inspiration. Particularly the surrealists recognized the creative possibilities and added value that could be unlocked by giving free rein to the psyche’s powers. They adopted the 1922 publication Artistry of the Mentally Ill, authored by the Heidelberg-based psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, as their bible. The mid-century period then saw Jean Dubuffet introduce the notion of “art brut”, a mode of creativity that seeks out and finds the raw, unadulterated, undeformed, and anti-academic, an art removed from cultural norms. Works by autodidacts and supposed misfits also featured in Roger Cardinale and Victor Musgrave’s legendary 1979 exhibition Outsiders in London. And in Austria, the psychiatrist Leo Navratil established the House of Artists in Gugging—discovering pioneers such as August Walla and Johann Hauser for the broader art world. Black Art Matters: It was in the wake of major civil unrest in 2013 that the Black Lives Matter movement formed in the USA. By just one year later, following numerous demonstrations sparked by African American deaths particularly at the hands of white law enforcement officers, it had achieved worldwide awareness thanks to the lightning-fast spread of information and news across social media accompanied by the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. In art, the politicization and sensitization of broad swaths of society to racism, (police) violence, and aggression as well as to social discrimination against people of African descent found strong resonance in the 1980s works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, just as they also have in the contemporary art of recent years. New African voices are taking positions and creating new visibility, with art by and portraits of BIPoC persons serving to ensure the presence of those who had long been underrepresented in the history of Western art. Today’s artists engage deeply with questions of class, race, and gender, in which context they also turn a criticize eye on white supremacy—defined as the hegemony of white people, their worldview, and their influence in society. Obsessions: Obsessions can be understood as individual myths, as internal forces that take the self by surprise again and again. Obsessive forces lead to compulsive eruptions, to unimagined degrees of intensity and internal necessity. Fraught with personal and societal taboos, they frequently manifest themselves in secret and without witnesses. Obsession features as an indispensable ingredient in numerous artists’ biographies, which are transfigured by this elixir of life fed by a mysterious source. Obsessions write life stories, drastically reshuffle existences, propel the highest achievements—and can also destroy. Those who know them regard them with both love and hate, while those unfamiliar with them feel excluded from the Olympus of the initiated. Particularly those individuals who apply themselves to art are nourished by a fierce drive that can thwart efforts to realize enlightened life designs or calculate strategic decisions. Whether obsession in fact reveals a golden thread that runs throughout a person’s life, and whether obsessions cause people to race toward both good fortune and ruin in defiance of all decency and morality—such questions must remain open.

Grotesque Figures: It was long the case that high culture had turned its back on the grotesque, impure, and inscrutable, giving itself over to just proportion and the harmoniously consummate, shunning rulelessness and divergence from the norm. The grotesque, on the other hand, is ever in search of difference and divergent beauty. It questions form’s ideality and liberates itself from classicist creative principles. In holding up a mirror to the world, artists distort, overextend, and upend reality in carnivalesque fashion, discovering the fantastical, deformed, and occasionally kitsch. The grotesque body as demonstrated by Eva Beresin and Franz Ringel is not a self-contained whole; it is unfinished, fragmentary, transformative, continually metamorphosing. Ines Doujak’s figures unite the beautiful with the ugly in a bizarre manner, rendering the repulsive and disgusting worthy of visualization. And Jonathan Meese’s grotesque bronze figures embody an expression of the shocking, exaggerated, and ambivalent, allowing one to peer behind the facade of an all-too-smooth surface into the terrifying abysses of human existence. Hybrid Forms: Hybridity is the key concept in light of which to describe cultural diversity, multimediality, and heterogeneity. The Latin term hybrida denotes something of mixed origin and has to do with the melding of human and animal, woman and man, artificial and natural, and hence with the mixing and recombination of different systems, languages, and genders, with the collision of cultures, and with combining the (supposedly) contradictory. Differences are not melded together but instead persist openly and alongside one another in their distinctness. Hybrid beings defy classic attributions and clear categorizations, with purity requirements having become obsolete. Artists today invoke identity’s reorientation: by exposing and engaging with gender, artists such as Grayson Perry and Verena Bretschneider question conventional role models. August Walla, on the other hand, goes so far as to concern himself with a new world order: in his neologism-laced pictorial exegeses, he combines various worldviews as well as elements drawn from politics, religion, and myth. Dream and Trauma: A metaphor of origin to be found in art holds that the dark and unordered, the formless and chaotic stands at the beginning of any aesthetic production. Peculiar to both art and dreams is a reality status that excludes the enlightened and managed outside world with its utilitarian rationality and fixation with functionality. The artistic added value of the mysterious, ambiguous, and cryptic arises from the labyrinthine tangles that constitute the subsurface pathways of consciousness. Traumatic occurrences, things repressed and forgotten can manifest themselves in the imaginary aspects of art and dreams. Like the proverbial tip of the iceberg, events pushed out of daytime awareness can crop up in those places, situated halfway to the clarity of consciousness, where internal images are permitted. The task of the imagination’s machinery is to shift, in a constant act of rotation, that which has been overlooked, painfully repressed, and marginalized out of latency and into the realm of the evident so that it may be acknowledged by the psyche. Drawing on a visionary power that pushes toward visibility, artists like Aïcha Khorchid banish their fears and stride forth to process traumatic experiences, abuse, and violence. Inclusion: The inclusion of artists from continents such as Australia, Africa, Asia, and South America is an important priority in contemporary art that undermines the exclusivity of Eurocentric thought and action and of Western art and culture. The invocation of other cultures embodies an ex negativo attempt to question our faith in limitless progress, growth-based capitalist utopias, global digitization, and the increasing virtualization of our world. In Aboriginal art, one sees this in the output of artists such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Nyunmiti Burton, who take up ancestral stories such as that of the Seven Sisters. The rediscovery of indigenous myths and age-old cultural techniques, rituals, artisanship, and textiles, though it might initially seem to run counter to Western civilizations’ high culture-derived self-understanding, represents an enrichment of the canon. Autochthonous peoples’ belief in the collective power of community puts the lie especially to egocentric worldviews that manifest in a cult of genius.

Works by: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Eva Beresin, Amoako Boafo, Verena Bretschneider, Cecily Brown, Nyunmiti Burton, Miriam Cahn, Alexandre Diop, Ines Doujak, Jean Dubuffet, Stefanie Erjautz, Jadé Fadojutimi, Gelitin/Gelatin, Aïcha Khorchid, Soli Kiani, Basil Kincaid, Jürgen Klauke, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Elena Koneff, Maria Lassnig, Daniel Lezama, Angelika Loderer, Claudia Märzendorfer, Jonathan Meese, Sungi Mlengeya, Tracey Moffatt, Michel Nedjar, Tony Oursler, Grayson Perry, Marc Quinn, Franz Ringel, George Rouy, Iris Sageder, Cindy Sherman, Sarah Slappey, Kiki Smith, Tal R, VALIE EXPORT, Jannis Varelas, August Walla, Franz West, Kennedy Yanko

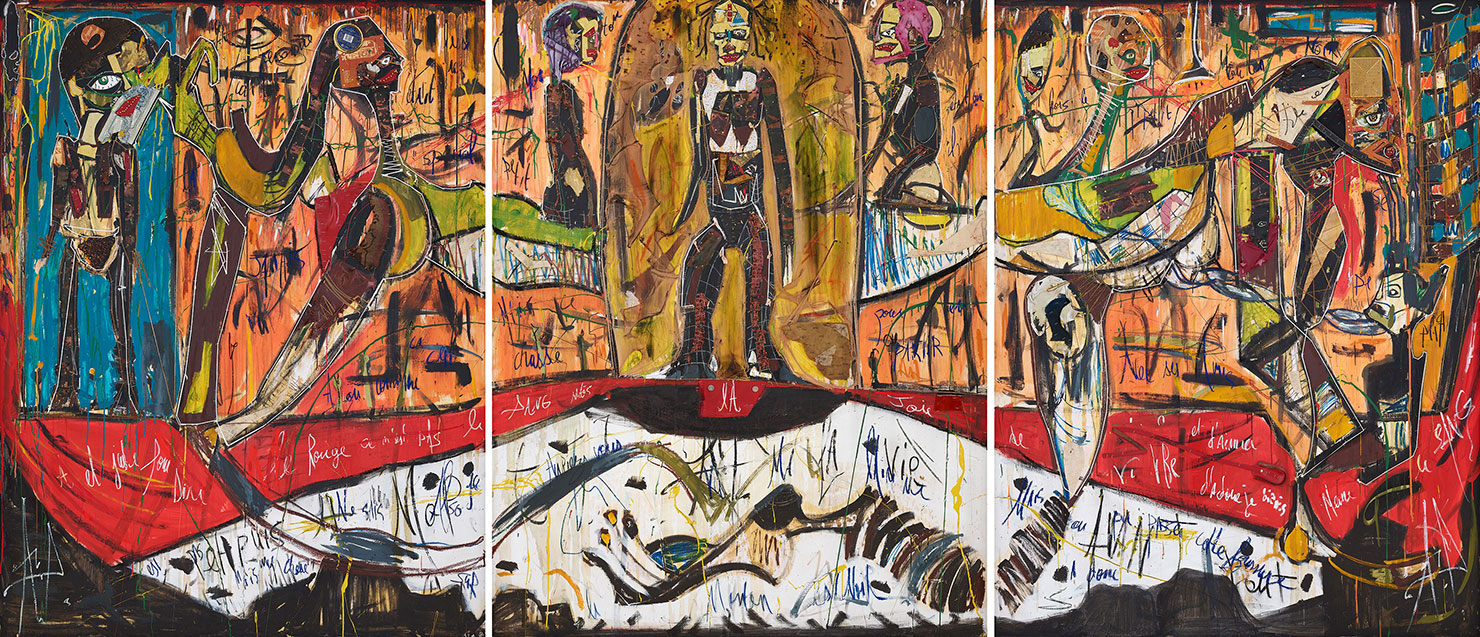

Photo: Alexandre Diop, Il était une fois le Mouton Noir, 2021, Mixed media on wood, The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna © Alexandre Diop

Info: Curator: Angela Stief, Albertina Modern, Albertinaplatz 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 12/2-18/8/2024, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00, www.albertina.at/en/

Right: Verena Bretschneider, Adam, 1989, Material image, The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Collection Dagmar and Manfred Chobot © Verena Georgina Bretschneider

Right: Amoako Boafo, Ivy Off Shoulder Dress, 2023, Öl auf Leinwand, The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Haselsteiner Family Collection © Bildrecht, Vienna 2024, Photo © Sandro E. E. Zanzinger

Right: Gelitin/Gelatin, MONA LISA (2184), 2020, Plasticine, paraffin, beeswax and pigments on wood, The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Haselsteiner Family Collection © Gelitin/Gelatin & Bildrecht Vienna, 2024