TRACES: Marcel Broodthaers

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Belgian artist, poet and filmmaker Marcel Broodthaers (28/1/1924-28/1/1976). Although he produced art for only 12 years, Marcel Broodthaers initiated a critique of post-war Modernist art practice that remains central to the concerns of Belgian sculptors who have emerged in the two decades since his death in 1976. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Belgian artist, poet and filmmaker Marcel Broodthaers (28/1/1924-28/1/1976). Although he produced art for only 12 years, Marcel Broodthaers initiated a critique of post-war Modernist art practice that remains central to the concerns of Belgian sculptors who have emerged in the two decades since his death in 1976. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

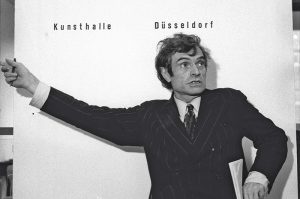

By Dimitris Lempesis

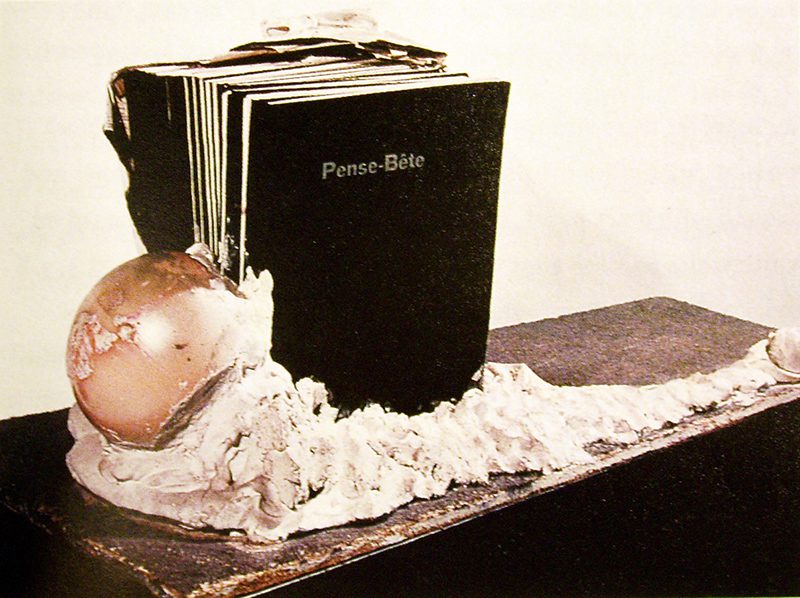

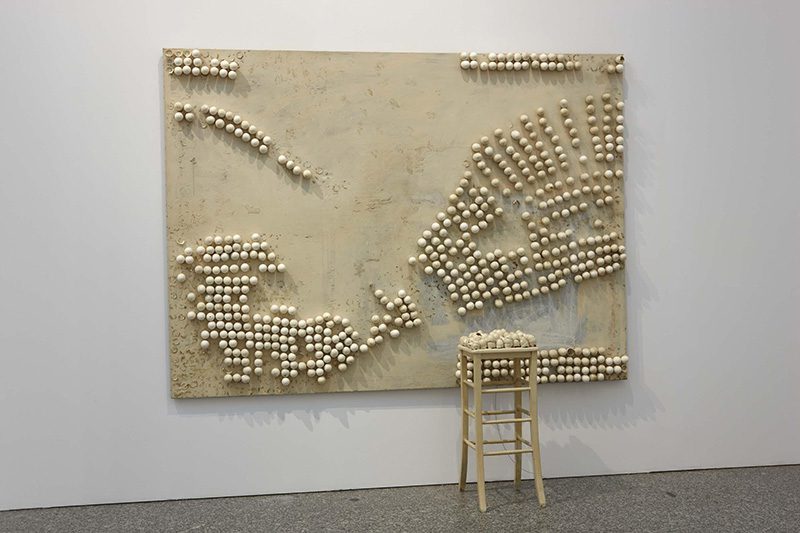

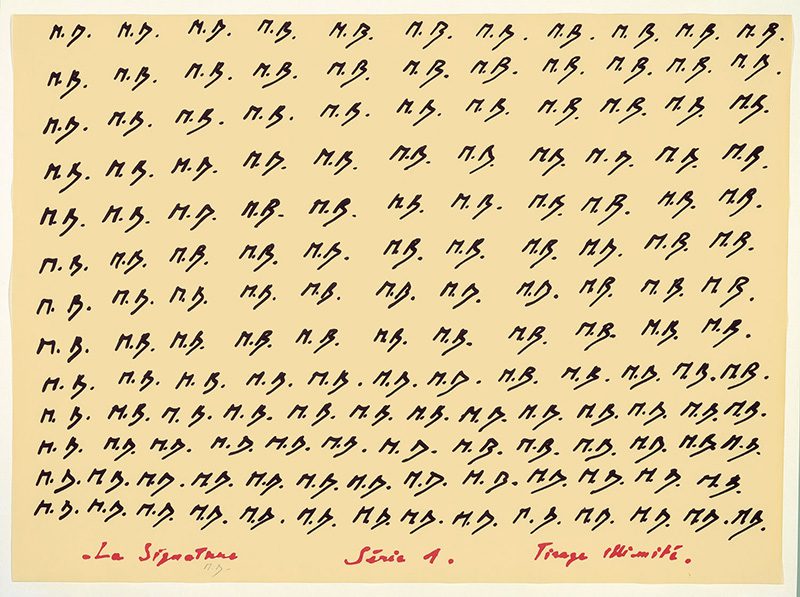

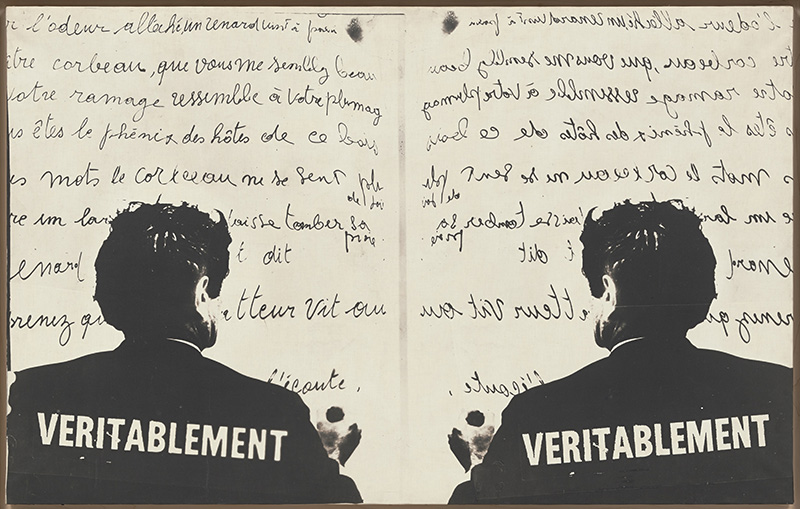

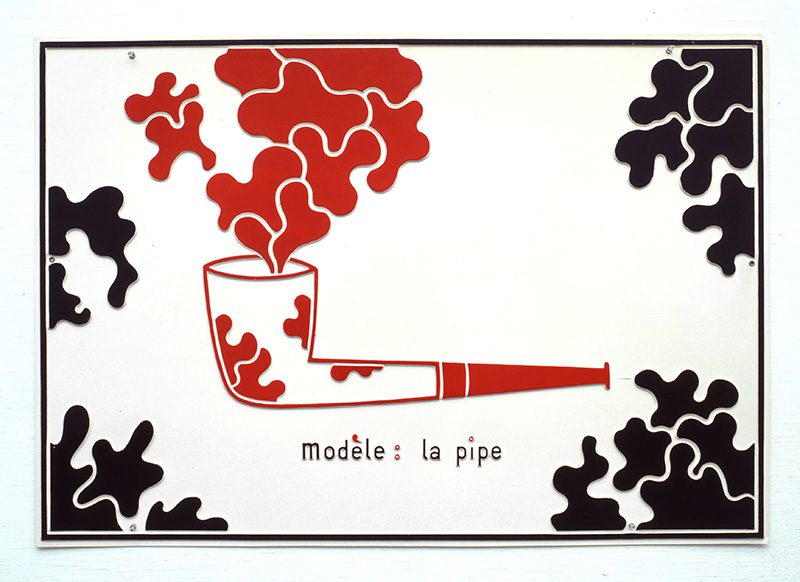

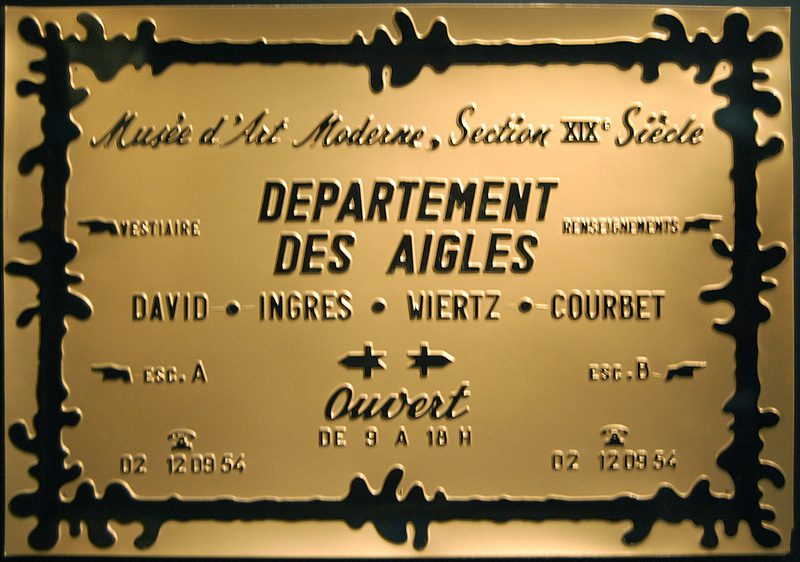

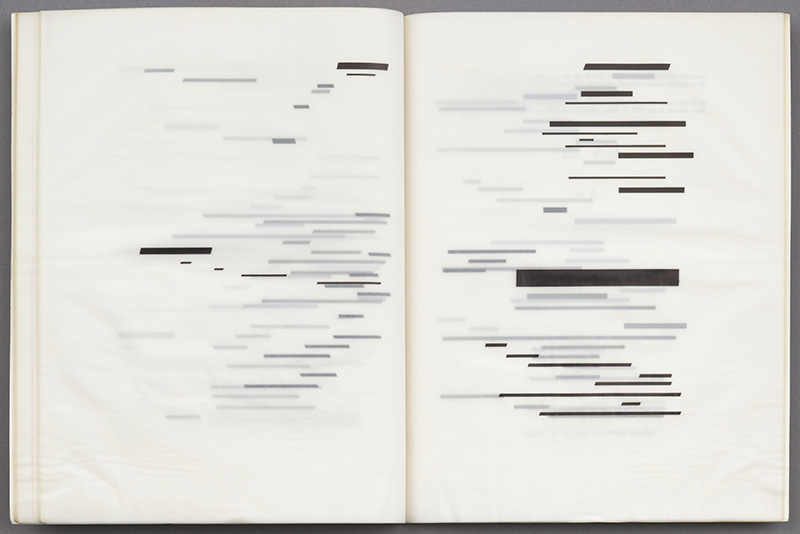

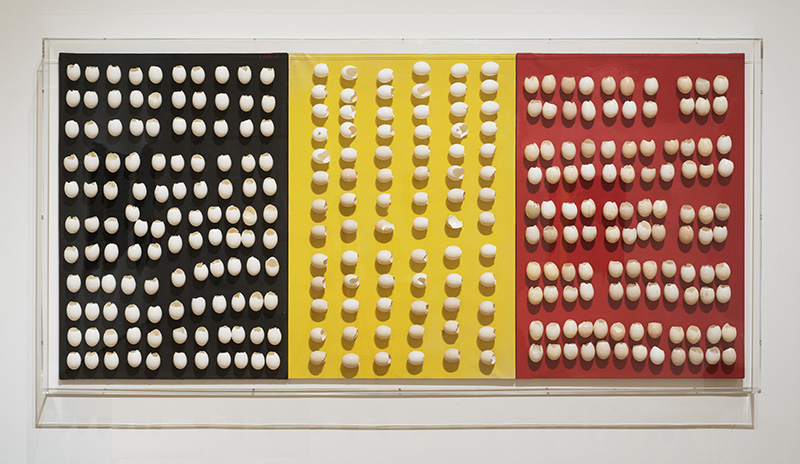

Marcel Broodthaers was born in Brussels, where he was associated with the Groupe Surréaliste-revolutionnaire from 1945 and dabbled in journalism, film, and poetry. At the end of 1963 he decided to become an artist and began to make objects. For his first solo exhibition, he encased 50 unsold copies of his latest poetry book, “Pense-Bête”, in plaster, turning them into a sculpture. Broodthaers began his career making sculptural objects from the discarded materials of the good life. Mussel and egg shells or molds that shaped their contents over a period of time-became for the artist apt metaphors for the process of making art and the pleasurable rewards of middle-class taste. Fragile and without function or value, these shells were paired by the artist with materials from the art world such as paint, geometric forms, canvases, frames, and pedestals. To make art out of life was not unusual in this period. Broodthaers’s contemporaries Piero Manzoni, Joseph Beuys, George Segal, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenburg also drew inspiration and materials from everyday life. But the Belgian artist exposed the rupture between the artwork and the aesthetized object as well as calling attention to the lack of originality or uniqueness within artistic production, which gave his art its peculiar parodic thrust. Broodthaers incorporated written language in his art and used whatever was at hand for his raw materials not only mussel and eggs shells but also furniture, clothing, garden tools, household gadgets and reproductions of artworks. In his “Visual Tower” (1966), Broodthaers made a seven-story circular tower of wood. He filled each story with uniform glass jars, and in every jar he placed an identical image taken from an illustrated magazine, of the eye of a beautiful young woman. For “Surface de moules (avec sac)”, he glued mussels in resin on a square panel; in 1974 the artist added a discreet metal hook to the centre of the work designed to support a shopping bag filled with mussel shells. From 1968 to 1975 Broodthaers produced large-scale environmental pieces that reworked the very notion of the museum. Broodthaers’s investigation of the role that presentation plays in the discourse of modern art practice gained complexity and political force with his numerous installations, collectively titled “Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicité”. First shown in his home in 1968, then in several museum versions, and finally installed at the 1972 Documenta (after which it was disassembled), “Musée d’Art Moderne” exposed the way in which the arrangement of things inscribes objects with both market value and ideology. Constructing a fictive narrative based on strategies of collecting and exhibition, Broodthaers entangles the museum audience in a never-ending circuit of looking that both reveals and obscures underlying networks of power and control. As he wrote in a text published in conjunction with the documenta version of this piece: “This museum is a fiction. In one moment it plays the role of a political parody of artistic events, in another that of an artistic parody of political events”. As part of the Financial Section, the artist also produced an unlimited edition of gold ingots stamped with the museum’s emblem, an eagle, a symbol associated with power and victory. The ingots were sold to raise money for the museum, at a price calculated by doubling the market value of gold, the surcharge representing the bar’s value as art. In 1975 Broodthaers presented the exhibition “L’Angelus de Daumier” at the Centre National d’Art Contemporain in Paris, at which each room had the name of a colour. In “La Salle Blanche” (1975), a life-size copy of a room of his home in Brussels, the wooden walls of the empty, unfurnished rooms were covered with printed words in French such as: museum, gallery, oil, subject, composition, images, and privilege, all intended to examine “The influence of language on perceptions of the world and the ways museums affect the production and consumption of Art”. He died of a liver disease in Cologne, Germany on his 52nd birthday. He is buried at Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels under a tombstone of his own design. For the next generation, those born after World War II, Broodthaers was a hard act to follow. Knowing that he had irrevocably changed the very process for viewing and understanding art, these artists incorporated Broodthaers’s ideas and manner of working into their own strategies for engaging the public in discussions of the role and function of art in contemporary life.

Marcel Broodthaers was born in Brussels, where he was associated with the Groupe Surréaliste-revolutionnaire from 1945 and dabbled in journalism, film, and poetry. At the end of 1963 he decided to become an artist and began to make objects. For his first solo exhibition, he encased 50 unsold copies of his latest poetry book, “Pense-Bête”, in plaster, turning them into a sculpture. Broodthaers began his career making sculptural objects from the discarded materials of the good life. Mussel and egg shells or molds that shaped their contents over a period of time-became for the artist apt metaphors for the process of making art and the pleasurable rewards of middle-class taste. Fragile and without function or value, these shells were paired by the artist with materials from the art world such as paint, geometric forms, canvases, frames, and pedestals. To make art out of life was not unusual in this period. Broodthaers’s contemporaries Piero Manzoni, Joseph Beuys, George Segal, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenburg also drew inspiration and materials from everyday life. But the Belgian artist exposed the rupture between the artwork and the aesthetized object as well as calling attention to the lack of originality or uniqueness within artistic production, which gave his art its peculiar parodic thrust. Broodthaers incorporated written language in his art and used whatever was at hand for his raw materials not only mussel and eggs shells but also furniture, clothing, garden tools, household gadgets and reproductions of artworks. In his “Visual Tower” (1966), Broodthaers made a seven-story circular tower of wood. He filled each story with uniform glass jars, and in every jar he placed an identical image taken from an illustrated magazine, of the eye of a beautiful young woman. For “Surface de moules (avec sac)”, he glued mussels in resin on a square panel; in 1974 the artist added a discreet metal hook to the centre of the work designed to support a shopping bag filled with mussel shells. From 1968 to 1975 Broodthaers produced large-scale environmental pieces that reworked the very notion of the museum. Broodthaers’s investigation of the role that presentation plays in the discourse of modern art practice gained complexity and political force with his numerous installations, collectively titled “Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section Publicité”. First shown in his home in 1968, then in several museum versions, and finally installed at the 1972 Documenta (after which it was disassembled), “Musée d’Art Moderne” exposed the way in which the arrangement of things inscribes objects with both market value and ideology. Constructing a fictive narrative based on strategies of collecting and exhibition, Broodthaers entangles the museum audience in a never-ending circuit of looking that both reveals and obscures underlying networks of power and control. As he wrote in a text published in conjunction with the documenta version of this piece: “This museum is a fiction. In one moment it plays the role of a political parody of artistic events, in another that of an artistic parody of political events”. As part of the Financial Section, the artist also produced an unlimited edition of gold ingots stamped with the museum’s emblem, an eagle, a symbol associated with power and victory. The ingots were sold to raise money for the museum, at a price calculated by doubling the market value of gold, the surcharge representing the bar’s value as art. In 1975 Broodthaers presented the exhibition “L’Angelus de Daumier” at the Centre National d’Art Contemporain in Paris, at which each room had the name of a colour. In “La Salle Blanche” (1975), a life-size copy of a room of his home in Brussels, the wooden walls of the empty, unfurnished rooms were covered with printed words in French such as: museum, gallery, oil, subject, composition, images, and privilege, all intended to examine “The influence of language on perceptions of the world and the ways museums affect the production and consumption of Art”. He died of a liver disease in Cologne, Germany on his 52nd birthday. He is buried at Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels under a tombstone of his own design. For the next generation, those born after World War II, Broodthaers was a hard act to follow. Knowing that he had irrevocably changed the very process for viewing and understanding art, these artists incorporated Broodthaers’s ideas and manner of working into their own strategies for engaging the public in discussions of the role and function of art in contemporary life.