PRESENTATION: Maryam Taghavi-مریم تقوی

Maryam Taghavi is an artist and educator. Her work on language and abstraction in recent years has coalesced with research on Islamic occult practices. More specifically, the branch of Simyia, which is the practice of making sigils, or spells by arrangements of Arabic letters and numbers. In reincarnation of these sigils, within a range of disciplines such as painting, drawing, sculpture, performance, publication, and installation, she intends to release the movement withheld in these forms.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MCA Chicago Archive

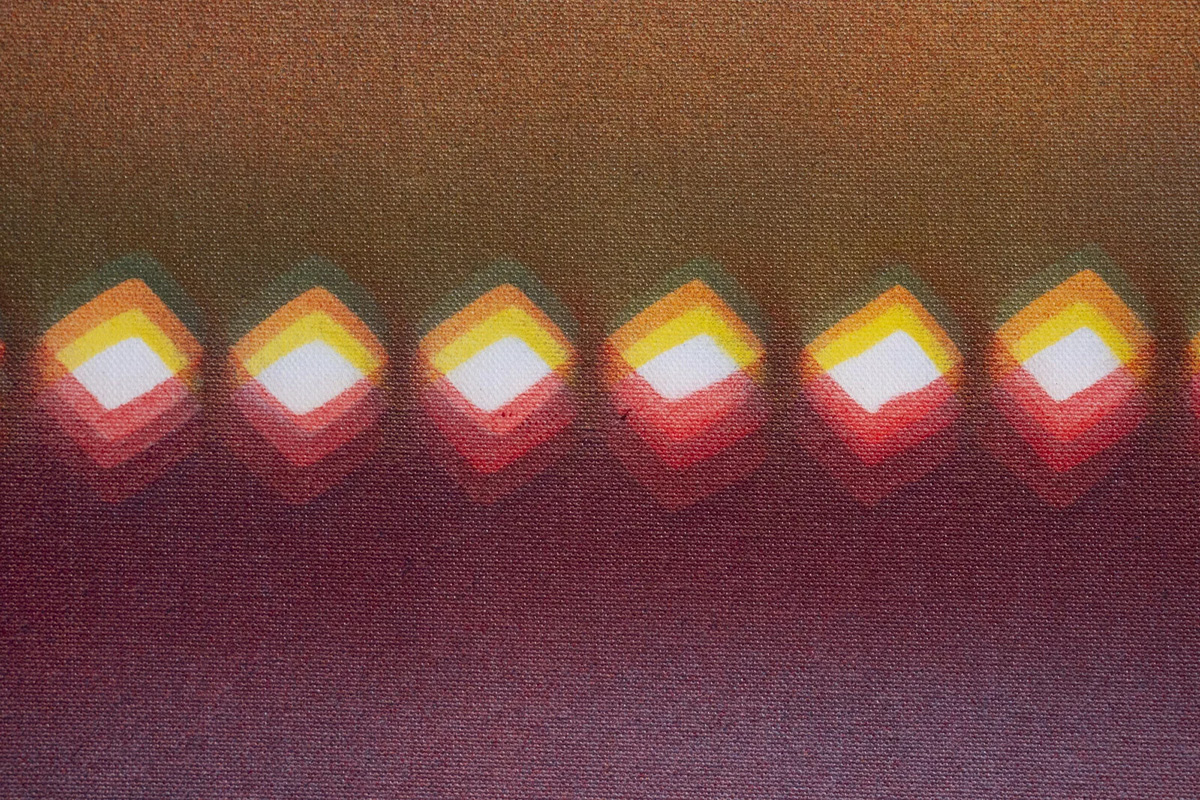

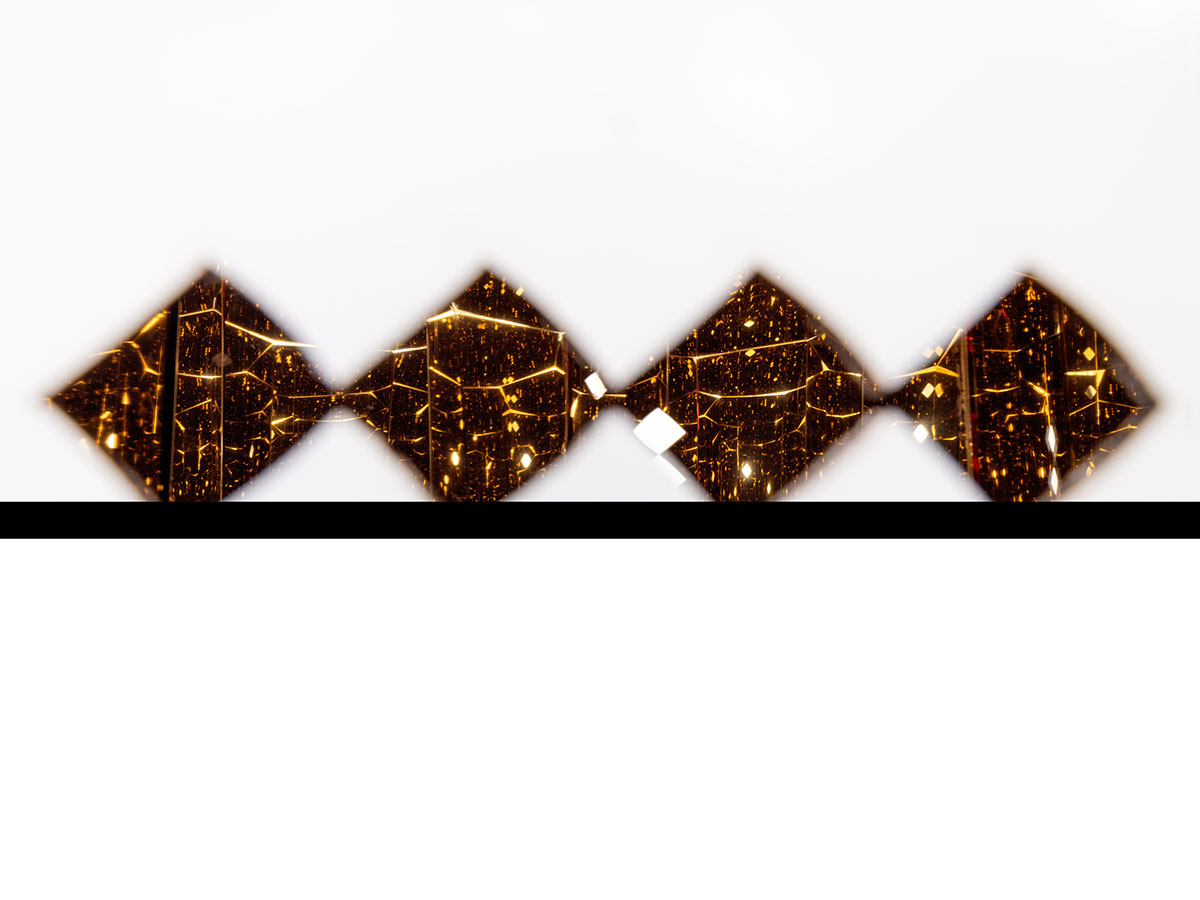

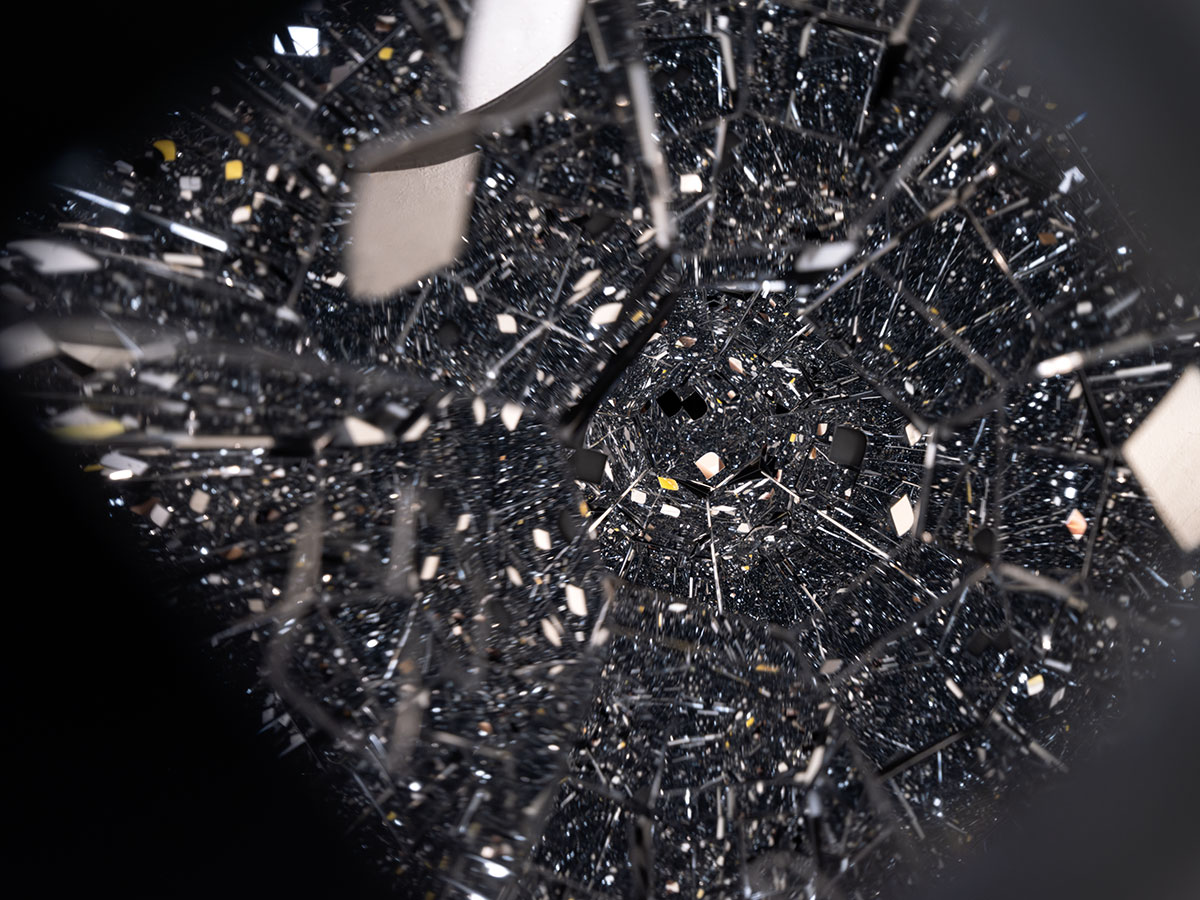

Maryam Taghavi’s practice insists on positionality: where one stands determines what—and how—one sees. For the past several years, her work with talismans, calligraphy, and the Islamic occult has coalesced into a series of sculptures and paintings that strive to signify the unseen. In her exhibition “مریم تقوی” , Taghavi creates new works that expand her interest in perception by interrogating the space between the illusive vanishing point of the horizon and the immutability of distance. Taghavi’s exhibition “Nothing Is” is culminating in an immersive installation that invites audiences to close one eye and peer with the other, to adjust their gaze to new spatial possibilities, and to imagine a relationship with what is imperceptible. Before visitors enter the exhibition, they are welcomed by a series of cut-outs in the shape of noghte(s) made in the external gallery wall, part of a piece called “Quadrilateral view” (2023). When visitors peer through this aperture on either side of the wall, they encounter a mirrored prism installed within. This prism houses countless reflections of the noghte motif, a nod to the concept of infinite possibility in Islamic geometric patterns. Here, Taghavi carefully manipulates materials and light to create something that transcends physical constraints to become infinite and, perhaps, magical. Taghavi’s prisms, including this one, are mobile vessels that manifest in different ways each time they are installed in a new space, revealing many versions of infinity. A second prism, “Pentagonal view” (2023), is revealed upon entering the exhibition. It is housed within the wall of another work—a site-specific architectural intervention titled “Hashti” (2023). Designed by Taghavi, the walls of this space form a twelve-sided shape, or dodecagon, modeled after a geometric space in Persian architecture. Known as the hashti, this liminal area connects the gate or entrance of a building and the doorway leading to the interior. Traditionally, the hashti serves as a mediator between outside and inside—a place to pause and acknowledge transition. As visitors progress from “Hashti” into the second gallery, Taghavi decisively pulls back the curtain to offer a glimpse into the innerworkings of her process. She reveals the reality behind her prisms by displaying a third prism, “Unfolded Hexagon” (2023), unwrapped, or disassembled, on the floor of the gallery, and a fourth, “Triangular View” (2023), installed as a free-standing sculpture with which visitors can interact. Here, Taghavi affirms the magic inherent to these works—and then purposefully negates it by revealing the illusion. Nearby, six of Taghavi’s paintings from the series “Horizon” are set against a dark green background. These large-scale, airbrushed works evoke a fragmented horizon, suggested by the familiar noghte, which appears in clusters of three, five, or ten. Taghavi describes the horizon as “the place where the earth meets the sky, an imagined line that our eyes make up, a distance we cannot reach . . . I think there’s something incredibly powerful about that mode of imagination.”[3] Nodding to the noghte’s origins as a form of measurement, these works invite the viewer to consider that uncertain line, and the assumptions their eyes make about its distance. By pushing back on the viewer’s perception of space, Taghavi’s paintings engage with a longstanding artistic tradition prevalent in Persian miniature painting in which artists flatten the horizon line, thus obscuring the viewer’s depth perception. Historically, Western works of art were governed by the laws of perspective. Three-dimensional space was projected onto a two-dimensional canvas. Artists painted toward a vanishing point to mimic how distance is perceived in real life. While artists in the West concerned themselves with painting reality, Persian miniaturists “presented things as they should be, not necessarily as they are.” Objects in the background were not depicted as being smaller as they moved further from the foreground. Instead, they were placed at the top of the painting, where they remained proportionally the same size as those at the bottom of the painting. The miniaturists’ vertical approach invites the viewer to “perceive space in a more active way,” where “individuals become part of the whole picture, the whole surrounding space”. As an Iranian artist living in the diaspora for over twenty-three years, Taghavi’s practice can also be considered through the postcolonial writings of Homi K. Bhabha. In his book The Location of Culture” (1994), Bhabha writes, “The ‘beyond’ is neither a new horizon, nor a leaving behind of the past . . . we find ourselves in the moment of transit where space and time cross to produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion”. In Taghavi’s work, these crossings are both physical and imaginary. To live in the diaspora is to live outside of context. Similar to Taghavi herself, the noghte has been taken out of its literary framework. In the “Horizon” paintings, the noghte is fragmented, unable to complete the horizon line. It floats in isolation from the letters it ordinarily adorns, allowed only to hold its basic form. In other works, such as within the expanse of the artist’s mirrored prisms, the noghte is liberated, bending and morphing in the light, adjoined to nothing. Again and again in Taghavi’s work, we are asked to use our imaginations. To connect the dots, to dream of the horizon. To face incompleteness, and to exist in the in-between. Visitors to Taghavi’s exhibition encounter this dynamic in a work titled “Heechi” (2023). The sculpture is inspired by the artist Parviz Tanavoli, nicknamed the “father of Iranian sculpture,” who pointedly uses source material rooted in Iranian culture and translates it into modernist and abstract forms—such as in his “Heec”h series, which he began in 1965. Referencing both Persian literature and calligraphy, his series uses characters to spell out the Farsi word heech, which translates to “nothing,” a concept used in the Sufi spiritualism of renowned thirteenth-century poet Mawlana Jalal al-Din Muḥammad Rumi, whose verses explore the concept of nonbeing—not as the termination of being, but as the path to fulfillment and the wholeness of being. Though Taghavi’s sculpture “Heechi: is inspired by Tanavoli’s “Heech” series, she has added a single letter to the word, transforming “heech” into “heechi.” In contrast to “heech,” which represents a nothingness that leads to wholeness and fulfillment, the word “heechi” can be translated into a nothingness that represents emptiness and void. In Taghavi’s words, “that level of divine is removed from it. It’s very much looking down on earth and the everyday . . . [heechi is] the nothing as it appears in life’s disappointments or despair.” The final work in the exhibition is a small calligraphed text. It is the only work that contains multiple words. To create it, Taghavi commissioned calligrapher Parisa Shafiei to etch an excerpt from a poem [Ghazal #551] by the 13th century poet Saadi Shīrāzī in a style of calligraphy that is purposefully devoid of noghte(s). Without them, the reader needs to slow down to access the meaning of the text. The poem reflects on the state of longing and the persistence of a beloved’s memory. Elsewhere in the exhibition the noghte refracts through a prism or floats in a painting, separated from the context of letters. Yet here, in Taghavi’s final work, readers experience the inverse: the pure context of letterforms devoid of the noghte(s) that provide their discerning sounds.

Photo: Maryam Taghavi. Photo: Shelby Ragsdale, © MCA Chicago

Info: Museum of Contemporary Art, 220 E Chicago Ave, Chicago, IL, USA, Duration: 20/12/2023-14/7/2024, Days & Hours: Tue 10:00-21:00, Wed-Sat 10:00-17:00, https://mcachicago.org/