PRESENTATION: Antoni Tàpies-The Zen Imprint

Antoni Tàpies refined a visual language inspired by a wide range of sources that coalesce into a complex fusion of materials, gestures, and symbols. His exploration of Surrealist imagery early in his career served as the foundation for an ongoing investigation into the nature of physical objects and their materiality. Tàpies’ work embodied his extensive personal experience and history of his native Spain and specifically Catalonia. As Tàpies’ use of tangible materials for making art emphasize physical transformation, spiritual transformation is evoked through signs and symbols drawn from Eastern and Western cultures.

Antoni Tàpies refined a visual language inspired by a wide range of sources that coalesce into a complex fusion of materials, gestures, and symbols. His exploration of Surrealist imagery early in his career served as the foundation for an ongoing investigation into the nature of physical objects and their materiality. Tàpies’ work embodied his extensive personal experience and history of his native Spain and specifically Catalonia. As Tàpies’ use of tangible materials for making art emphasize physical transformation, spiritual transformation is evoked through signs and symbols drawn from Eastern and Western cultures.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fundació Antoni Tàpies Archive

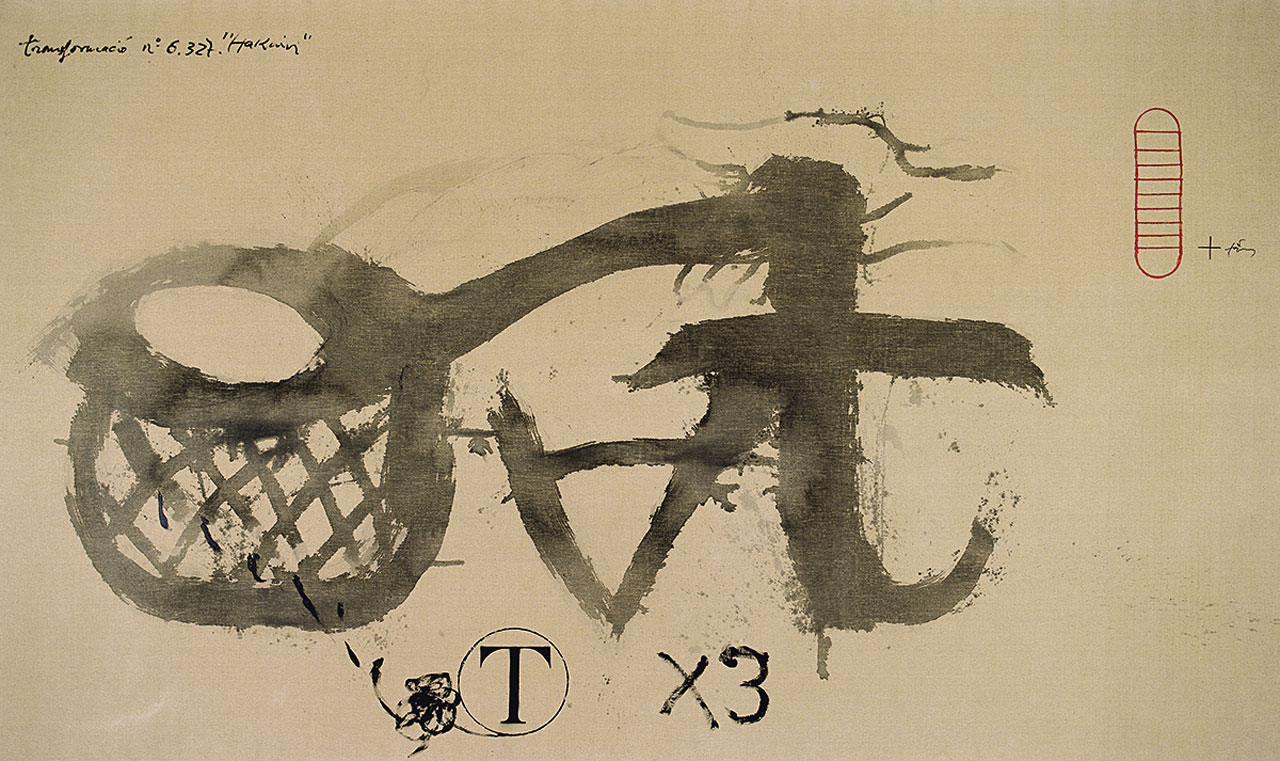

The exhibition “The Zen Imprint” coincides with the celebration of Antoni Tàpies’s centenary of birth, it includes a selection of forty paintings and drawings by the artist, some of which are being exhibited publicly for the first time. This exhibition focuses on Tàpies’ interest in the work of certain Japanese monks from the seventeenth to nine- teenth centuries who transmitted the teachings of Zen Buddhism, and who developed a critical attitude and a willingness to disrupt conventional values – including those of artistic practice –, such as Hakuin, Sengai, Jiun, Tōrei and Rengetsu. The exhibition shows how Tàpies integrated into his language many of the attitudes, images and techniques used by these artists. It was never a process of mimesis, but rather the assimilation of a way of working, and also of a vision of the world that the Japanese tradition has preserved in temples and gardens, poems and calligraphy, ceramics and paintings. This influence is evident in Tàpies’ works from the 1960s and 1970s, and especially from the 1980s, when he recovered the brushstroke, which he had almost abandoned in the matter paintings, associating it with inscriptions, writing and ideograms. From this time on, his paintings became less like walls and closer to drawing. The exhibition brings together a selection of works – both from the Collection fonds and from national and international loans – that will show how Tàpies’ approach to Japanese art left its mark on his work. Tàpies’ first contact with the cultures of Asia was through his father’s library, specifically through reading “The Book of Tea”, published in Catalan during the Republic. Later, through the writings of Heidegger, who started from a romantic tradition imbued with Eastern philosophy; Tsuneyoshi Tsudzumi’s books on Japanese art;22 and the writings of Lin Yutang on the Chinese and Hindu clas- sics, as well as on the different schools of Buddhism;23 all of them to be found in his father’s library. Tàpies saw in these readings, and in those that would come later – such as The Spirit of Zen and The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts, the essays on Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki, and the famous Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel, among others –, precedents for his own religious, political and intellectual non-conformism that he wanted to express in his artistic practice. Japanese haiku, especially through the work of Bashō, also interested him since it focused on ephemeral and everyday aspects of existence that Tàpies often brought to the fore. Many of the artists that had interested Tàpies in his formative years, such as Van Gogh, Gauguin, Le Douanier Rousseau, the Symbolists, Kandinsky, Miró24 –whom Tàpies considered a master–, even Wagner, had also turned their eyes towards Buddhism. Beyond the coincidence of the nine years that Bodhidharma spent meditating in front of a wall to attain enlightenment, some- thing that finds an echo in Tàpies’ mature work, the artist found in Buddhism in general, and in Zen in particular, a support for ideas and practices he deemed necessary and useful for affecting a change in behaviour in the contemporary world.

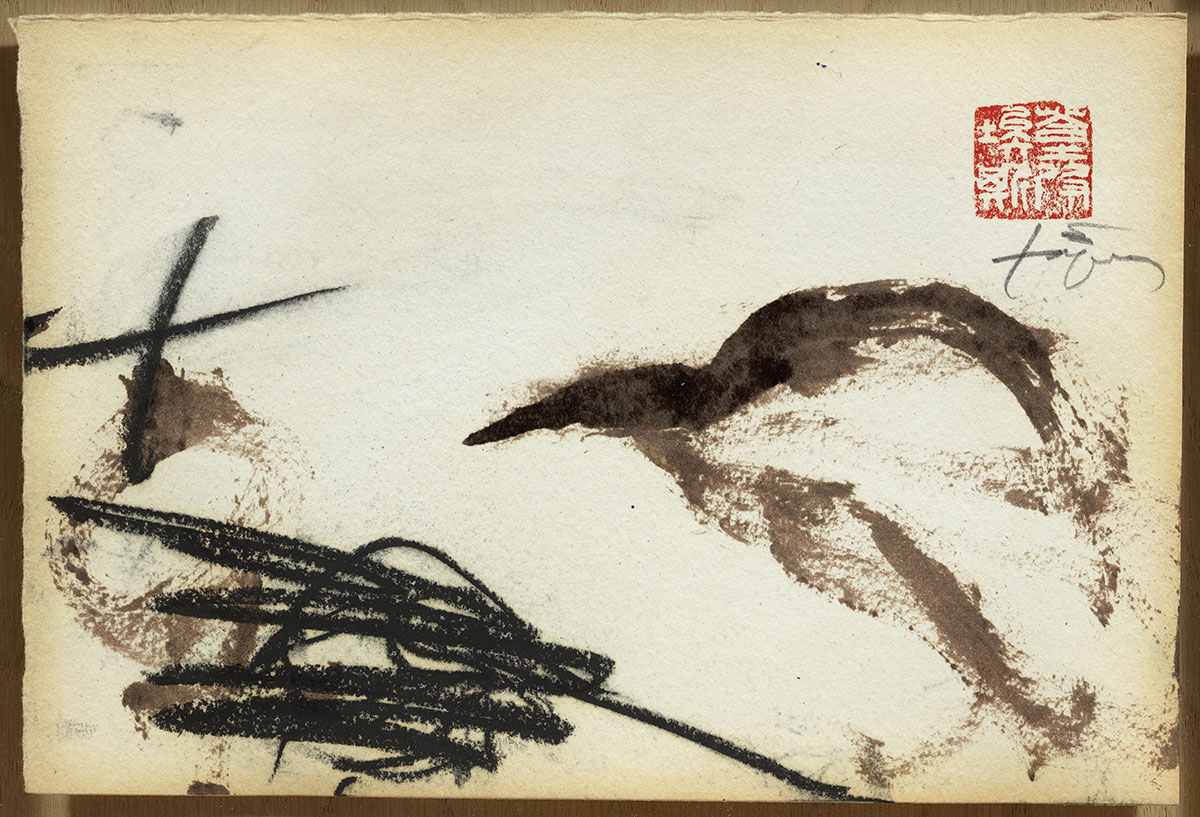

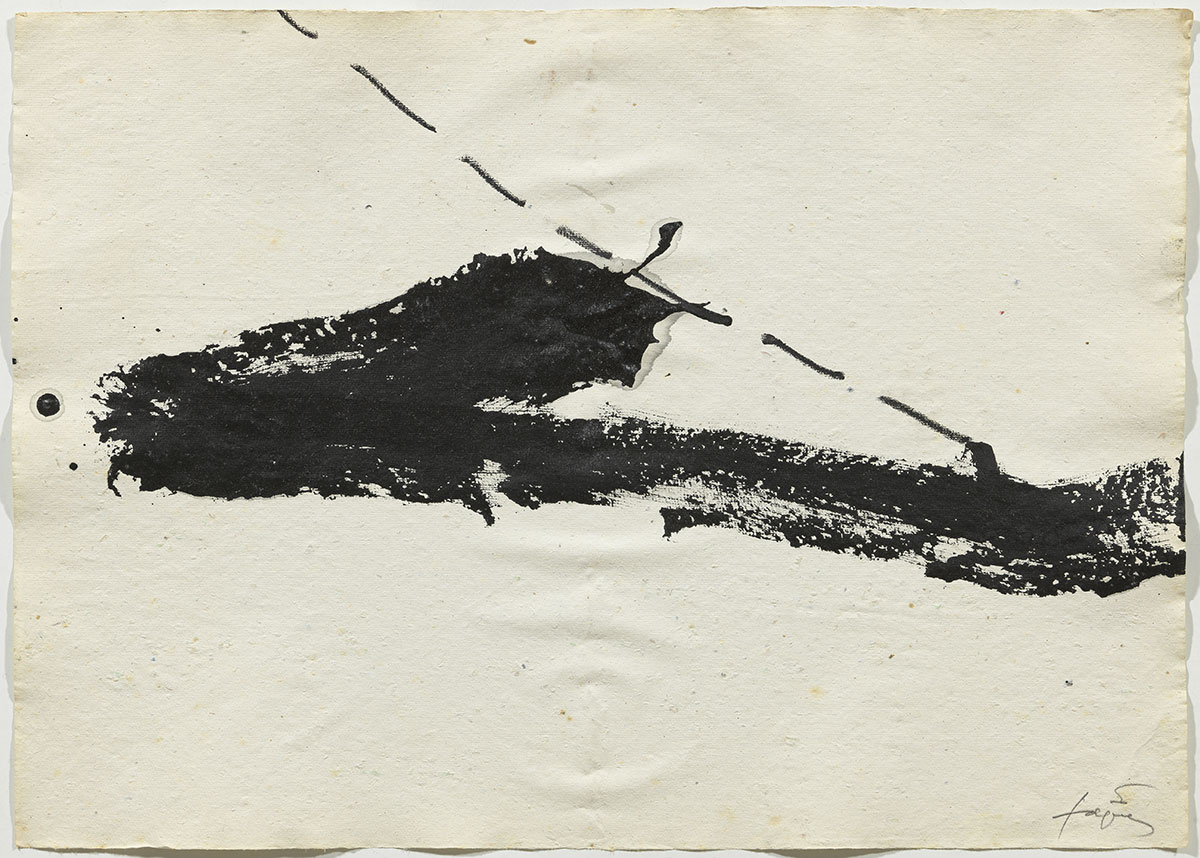

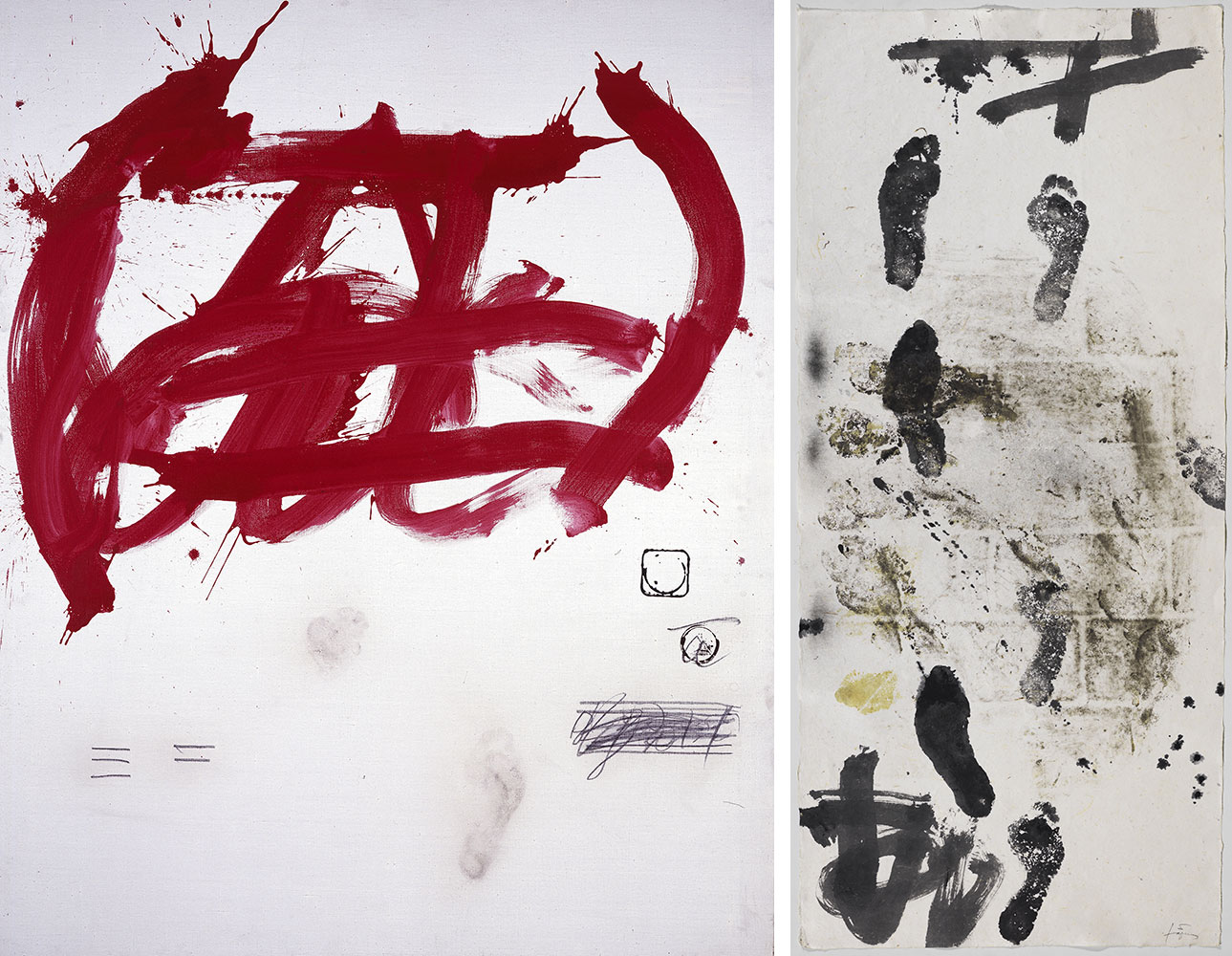

At the end of the 1950s, Tàpies began to relate to Japanese people, such as the poet Shūzō Takiguchi, with whom years later he would make the artist’s book Llambrec ma- terial26, and critic Takahiko Okada, co-founder of Provoke magazine. At the same time, his friendship with the art critic and Informalist theorist Michel Tapié, who had close links with Japan, would put him in contact with the visual artists of his circle: Domoto, Imai, Teshigahara, Yoshihara and especially the Gutai group, most notably Kazuo Shiraga, an artist who characteristically painted with his feet, and who became a Buddhist monk. In Tàpies’ works from the 1960s, we already find some traces of the influence of Zen such as minimal interven- tion, the importance of emptiness and, especially, the image of the ensō, one of the most profound themes of Zenga: a circle generally painted with a single brush- stroke and which has been interpreted as the whole, the void and enlightenment itself, and which Tàpies re- produced in watercolour, but also using string, rope, or wire since it was still the period when ‘poor materials’ characterised his mature work. It was also at this time that he created the scenography for the Japanese Noh play Semimaru (1966), an intervention that consisted of two ropes that traversed the stage from side to side in the form of an X, and from which hung a knotted white handkerchief and a walking stick. In the 1970s, and especially from the 1980s until the 2000s, Tàpies returned to the sparing use of the brush, which he had abandoned during matter paintings, and which he now associated with writing and calligraphy. From this moment on, his paintings became closer to drawing, with fewer references to walls. In the works of this pe- riod, he recovers many of the images of the monk artists of the Edo period, such as the mountainous landscape– sometimes misty or cloudy –, animals, mushrooms; the objects of daily life – often linked to the tea ceremony; the self-portrait, a common theme in Tàpies’ career since the 1940s; and the reference to the transience of existence through the image of the skull or footprints. This last element is also an allusion to Buddha, who re- quested not to be represented by his likeness, but from the traces he had left in life, such as footprints or a chair he had sat on. Likewise, there are deities and patriarchs typical of the Zen tradition, such as the wandering Buddhist monk Hotei – deity of fortune, who is always represented with a bundle of old clothes, an image of- ten used by Tàpies himself –, as well as references to the Buddhist monks who influenced Tàpies, such as Hakuin, Sengai, or Rengetsu. Varnish and ink wash on canvas, wood, cardboard or paper, sometimes even Japanese paper, with uneven textures and accidental compositions, predominate in these works. Writing, impressions of objects and stamped imprints also abound. The immediacy of the gesture is intuited from the way of working, the way the whole body is put into the brushstrokes, the close identification between the subject and the object of the action, the non-duality. Before painting, Tàpies prepared by walking rhythmically around the studio, sometimes accompanied by a rhythmic sound, arousing his imagination, seeking deep concentration, and once he started working, the artistic action assumed the equivalent of meditation.

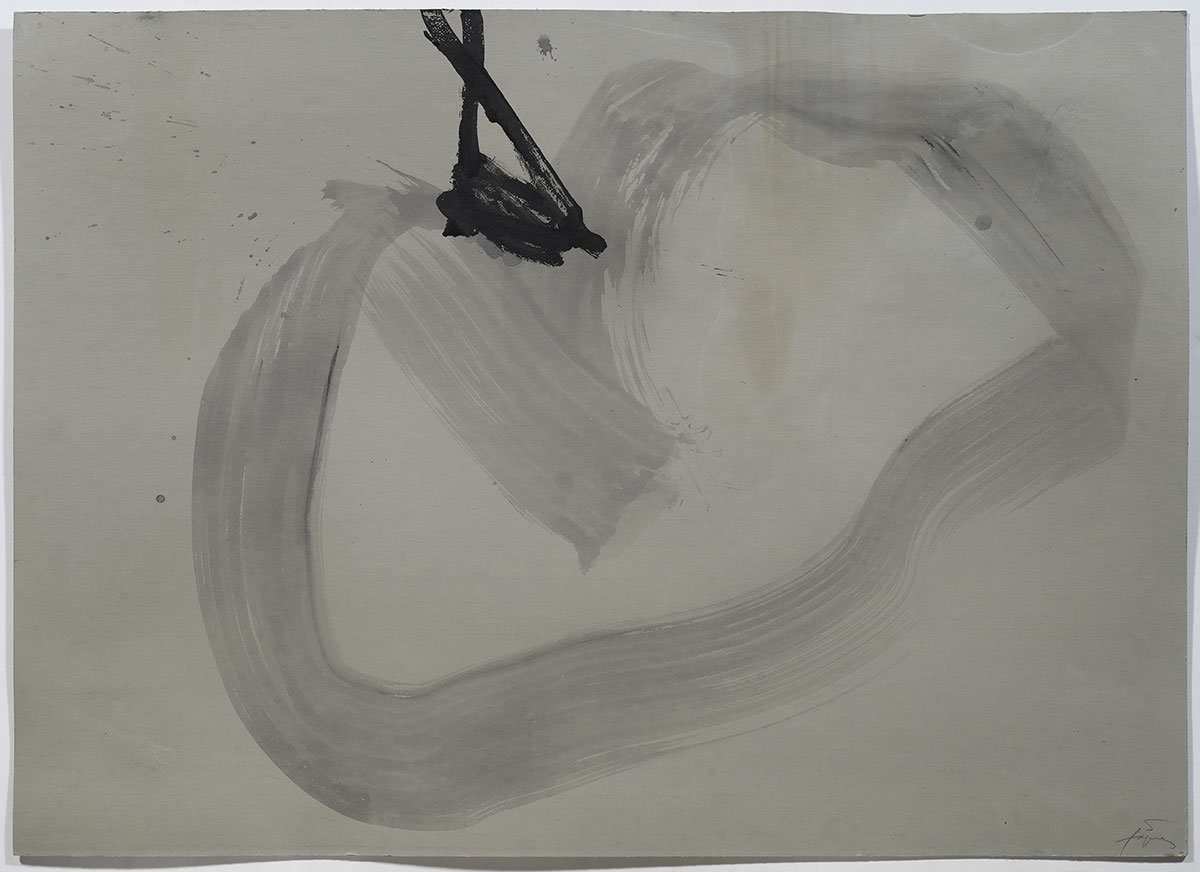

Photo: Antoni Tàpies, Pinzellada-paisatge, 1979, Paint and wax crayon on wrapping paper, 36 x 51 cm, Private Collection, Barcelona, © Comissió Tàpies / Vegap. De la fotografia: FotoGasull

Info: Curator: Núria Homs, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Carrer d’Aragó 255, Barcelona, Spain, Duration: 13/12/2023-23/6/2024, Days & Hours: tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, Sun 10:00-15:00, https://fundaciotapies.org/

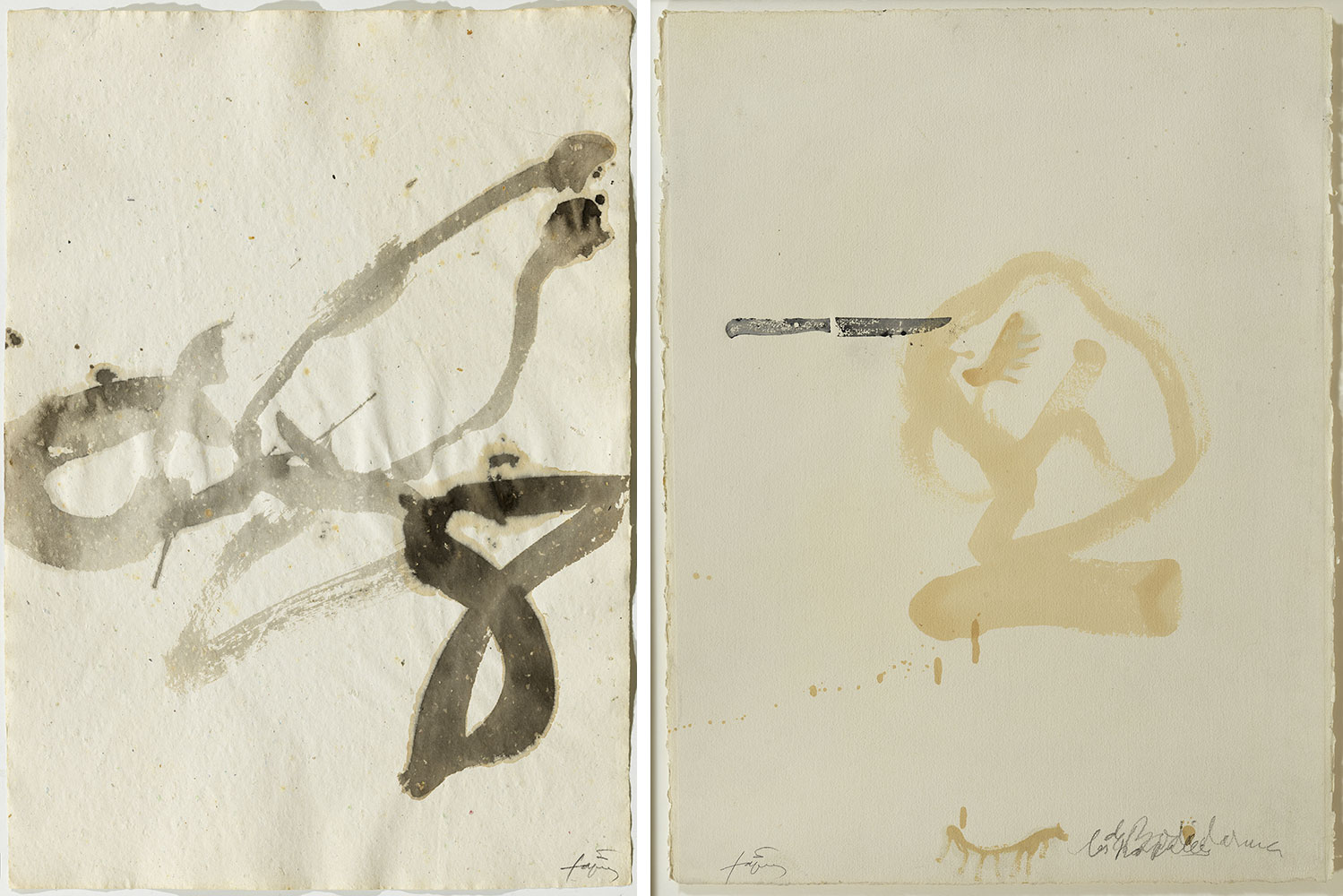

Right: Antoni Tàpies, Petjades i frottage, 2000, Paint and frottage on Japan paper, 158 x 71 cm, Private Collection, Barcelona, © Comissió Tàpies / Vegap. De la fotografia: FotoGasull

Right: Antoni Tàpies, Formes, 1982, Paint, varnish and pencil on paper 76 x 58 cm, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, © Fundació Antoni Tàpies / Vegap. De la fotografia: FotoGasull