PRESENTATION: Anselm Kiefer-Photography at the Beginning

Born in March 1945, a few months before the end of World War II, and based in France since 1992, Anselm Kiefer’s work is celebrated worldwide. Known and recognized for his monumental pieces, the artist will present over a hundred and thirty works at the museum, some of which are unpublished or produced for the occasion, testifying to his practice of photography and the question of image revelation, which is essential in his work but rarely addressed in exhibitions.

Born in March 1945, a few months before the end of World War II, and based in France since 1992, Anselm Kiefer’s work is celebrated worldwide. Known and recognized for his monumental pieces, the artist will present over a hundred and thirty works at the museum, some of which are unpublished or produced for the occasion, testifying to his practice of photography and the question of image revelation, which is essential in his work but rarely addressed in exhibitions.

By Dimitris Lempesi

Photo: LaM Archive

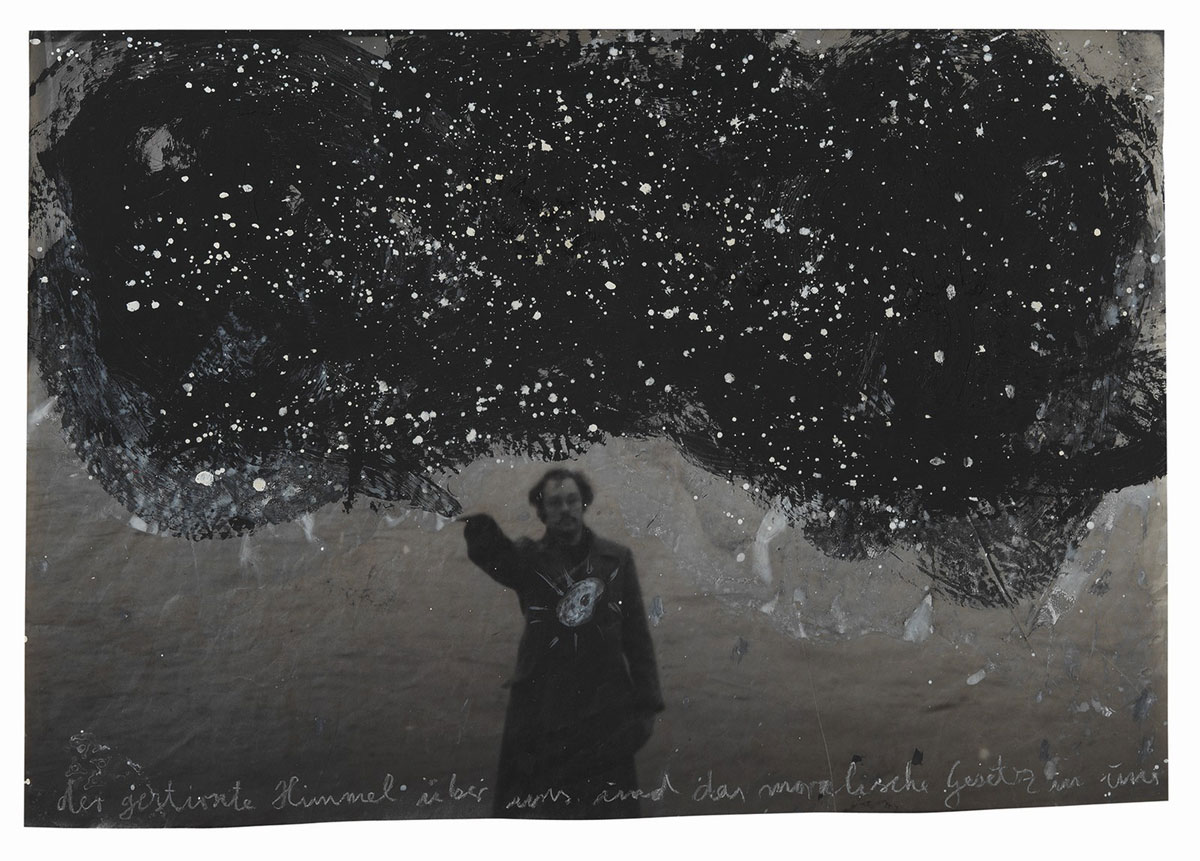

Marked by the devastated landscapes of his childhood, Anselm Kiefer’s work has been engaged in a reflection on the origins of evil and the intimate exploration of the tragic nature of Nazism since the late 1960s, resulting in a significant body of actions and photographs. After this radical beginning, the artist focused on painting, sculpture, and bookmaking, working on themes that, supported by his profound knowledge of literature and rooted in German history, span many domains: myths, architecture, destruction, alchemy, Kabbalah, and even geophysics. Although he claims to think in images and always uses photography to create his paintings – even calling it a “sacred auxiliary” – Anselm Kiefer has rarely, if ever, fully presented this essential component of his work. The exhibition “Photography at the Beginning” at LaM is the first to take stock of his photographic practice, which has discreetly accompanied his entire trajectory up to the present day. The thematic journey of the exhibition highlights this medium, which is at the origin of the construction of the poetic and visual world of his work. In the eight rooms, after the discovery of the early works of his career, the themes and inspirations that have nourished his approach over the past fifty years will be revealed, as well as some of the literary or mystical influences that he has celebrated through dedicated works. In contrast, paintings, books, and sculptures will show or comment on these ensembles and allow photography to be integrated into his work and appreciated for its beauty and precision.

1. Nigredo: Introduced by a self-portrait of the artist dressed in a crochet dress, holding a branch symbolizing nature and its regenerative power, the first room of the exhibition presents a series of works in which the artist confronts Nazism, a history that, in many ways, determined his youth. This encounter with the abhorrent is symbolized in the space by a more recent work, inspired by alchemy, which has interested the artist since the 1980s, called “Nigredo,” expressing the necessary dissolution of the putrid, the calcination of the vile, the first step in the process of transforming matter – transmutation. In 1969, still a student, Kiefer was aware of the continuing silence in German civilian life regarding its recent past. He then embarked on actions in Switzerland, Italy, and France, known as “Besetzungen,” or “occupations.” To create these works, he donned the uniform of a Wehrmacht soldier that his father had worn during the war and photographed himself performing the Nazi salute at selected sites. For Kiefer – who incorporates the thinking of Carl Gustav Jung, believing that it is only when evil is recognized as a part of oneself that it can be controlled and overcome – these “occupations” are not merely provocations but the integration of taboos into the artistic process. Misunderstood, these works caused a scandal in Germany when they were published in 1975. During the same years, the artist was captivated by the writings of the French writer Jean Genet, to whom a self-portrait makes reference at the back of the room. Nonchalantly reclined and dressed in a robe, the artist performs a caricatured Nazi salute. The photograph, affixed to a lead sheet, an essential element in alchemical transformation, is then altered by a chemical electrolysis process. The work becomes colored with oxides, thus manifesting the transformation of the image, its transmutation.

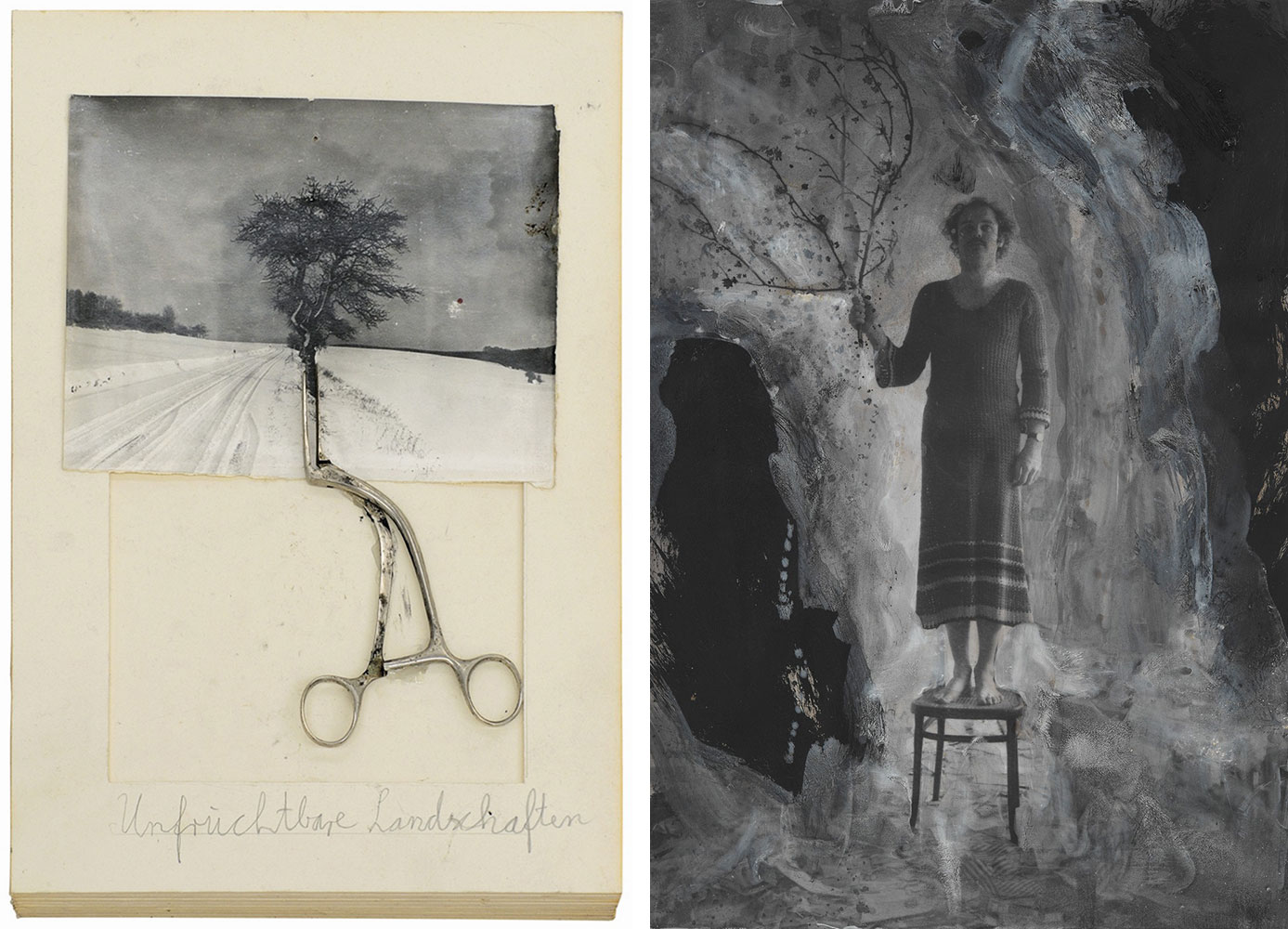

2. Unfruchtbare Landschaften: Since the late 1960s, Anselm Kiefer has continuously created unique books using photographs and various materials. These works in a way constitute his intellectual biography, “his intimate labyrinth.” In them, one can trace his thoughts, references, and a deep work of memory, that of a German artist born after the war. In 1969, Kiefer submitted two of these books for his final exams. The first, titled “Heroic Landscapes,” gathers some of his photos of “occupations” and alludes to the Nazi theory developed in 1943, suggesting that art competition is necessary for the greatness of the Third Reich. The second, “You Are a Painter,” features on its cover the portrait of Grünewald, a mythical artist of German Renaissance painting, portrayed as a prophet by the Nazi sculptor Josef Thorak. These two books stage the ideal of art corrupted by ideology and the mission of the young artist who is beginning his career and must regenerate art damaged by history. Apart from the personality of Jean Genet, the works gathered here are marked by German history, notably “Operation Sea Lion,” which revisits Hitler’s invasion project for England, in which Kiefer’s father was supposed to participate. This collection also presents the violence that the artist inflicts on landscapes. “The Flooding of Heidelberg” illustrates this well, as does “Cauterization of the Buchen District,” a book composed of old canvases that have been destroyed and cut. In a similar vein, “Barren Landscapes,” to which gynecological instruments, IUDs, or surgical tools are affixed, or the abandoned railway lines that appear in “Siegfried’s Difficult Path to Brunhilde,” adorned with a tragic fire that spreads across the pages. These books manifest the impossibility of looking at these landscapes innocently, all marked by destruction and the horrors of the Holocaust.

3. L’écorce du monde: Grouped by themes, numerous photographic variations give an idea of the persistence of subjects in Anselm Kiefer’s work and the fecundity of his returns to one or another of his favorite themes. Most of these views can be found in his paintings – maritime landscapes, plowed lands, railroad tracks, flaming towers, wheat fields, sunflowers… – and they demonstrate the role of photographs, the discreet and continuous sources of his iconography, in the construction of the repertoire of his painting. In addition to this photographic inspiration, there is a collection of books created in response to his admiration for certain writers, a spiritual family with whom he maintains an intense dialogue. These are not illustrations but rather resonances, the enthusiasms of a captivated reader. He says about this: “I think in images. Poems help me do so. They are like buoys in the sea. I swim towards them, from one to the next; between two of them, I am lost without them.” Among these sources is “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” a foundational text of Mesopotamia that inspires actions and photographs, but more importantly, the Germanic myths that he reactivates, which had been contaminated by their use by the Nazis. Among the writers to whom he refers (Robert Fludd, Michelet, Bataille, Céline, Jabès, etc.), there are two great poets who accompany him continuously: Paul Celan, a Romanian, Jewish, German-language poet, with whom he shares a reflection on history and language, and Ingeborg Bachmann, who is, according to the artist, the greatest German-language poet of her time.

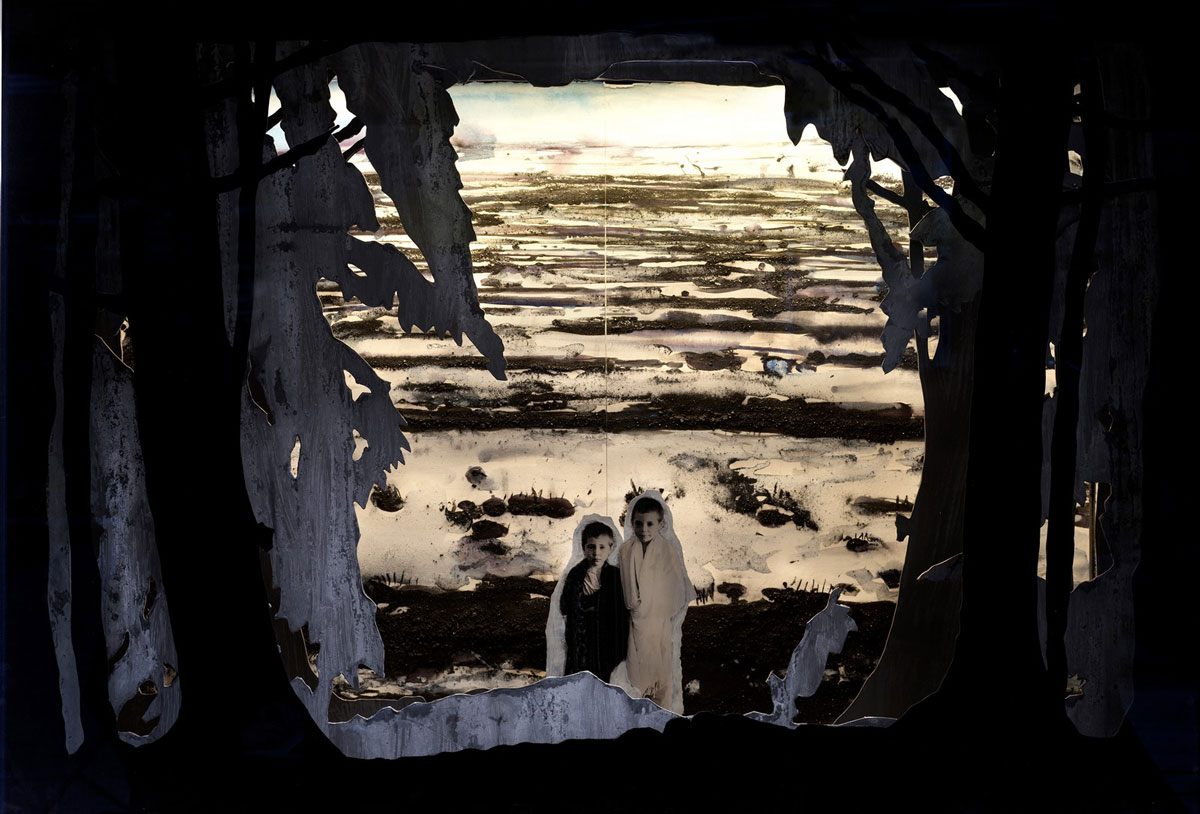

4. Familv Pictures: The collection presented in this room is dedicated to the intimate presence of photography throughout Anselm Kiefer’s life, he who claims to constantly photograph everything: “I constantly photograph. I take notes with the camera.” At the heart of the space, a large display case, specially designed for the exhibition, holds rolls of film that fall like lead phylacteries: “The films tell my life. The paradox is that the films are affixed to completely opaque lead. They are composed of photos I have taken throughout my life.” Rarely shown, an intimate diorama presents sixteen snow-covered showcases that borrow from family photographs, archives, blessed or purified by the snow that has settled on the trees, like particles of light slowly falling on the past. Private photographs, vintage images, friendly scenes, reminiscences arranged against the backgrounds of clearings in deep forests, those of the German soul. All of these personal moments are arranged without chronological order.

5. Lilith: Conceived in the shadow of Germany’s history, Anselm Kiefer’s work is imbued with the representation of ruins and explores the history of the world, within which the permanence of destruction is a central theme. This ensemble begins with a character from Jewish mythology: Lilith, Adam’s first wife, a rebel who roams in major cities, an uncontrollable seductress often symbolized by her long black hair in the artist’s works. Her name hovers over the sand covering a massive metropolis photo, foretelling its ruin. Further on, a display case containing fragments of destruction reveals a brain amidst shards and debris. It could be interpreted as the art’s ability to survive its own ruin, the paradox of an activity that only develops by destroying what precedes it. This cyclical nature of art mirrors that of civilizations. This is what is evoked by the large photograph on lead presented nearby, where corrosion suggests the cycle and mutation of forms and times. Titled “The Shape of Ancient Thought,” this work presents intertwined images of a Greek temple and an Eastern brickyard, allegories of history as the memory of ruins.

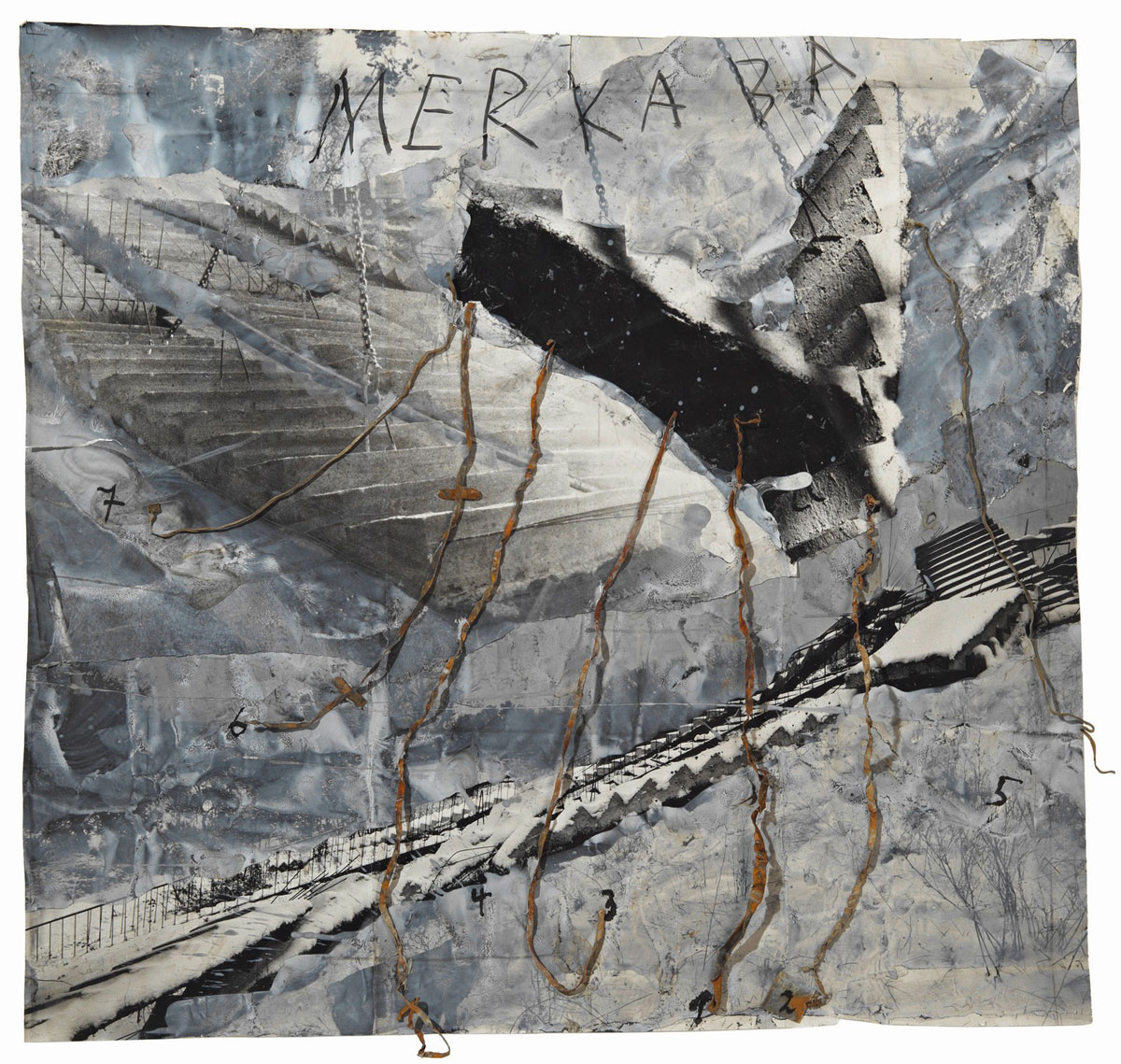

6. Merkaba: The study of German history leads Anselm Kiefer to take an interest in the original catastrophe and to examine religions, mysticism, and mythologies. The study of these grand subjects has led the artist to invent forms to signify these abstract concepts that usually elude representation, which was a new challenge for the artist. Inspired by the vision of the prophet Ezekiel in the Bible, the theme of Merkaba evokes a spiritual vehicle that, in Jewish mysticism, allows the ascent of the soul from the earth, traversing hostile spheres until it achieves unity. The towering structures in imbalance that the artist constructs in his estate in Barjac (Gard) become heavenly palaces, fiery palaces that the visionary traverses. These contradictory movements are symbolized with irony by the sculpture presented in the center of the room, an absurd yet symbolic bicycle whose scales carry the ingredients of the alchemical quest. The painting “Am Anfang” [In the Beginning] is a devastated primeval landscape, a theater of the struggle of the materials that presided over it, showing the endless creation-destruction of the world. The upright ladder evokes these ascendant movements of the spirit, but on it, like tatters, the images of life retained in lead unfold all the way to the ground, as if at the beginning there was the image. As if there were a symbiotic relationship between the absolute that is painting and images.

7. Athanor: The artist has always turned his studios – from the early ones in his childhood home to the one he occupied at the Academy, and the vast studios in a brickworks in Germany, in Barjac, or near Paris – into places of both work and play, of staging, and symbolic spaces for the maturation of his work. The artist’s studios are carefully arranged in a productive disorder and often appear in his drawings and photographs. They serve as the stage for the activity of the mind and its dialogue with matter, and can be likened to the alchemists’ athanor, the furnace in which matter undergoes transformation. Their labyrinths represent the artist’s journey. In Barjac, the artist photographed the underground spaces he had dug into the hill. They symbolize the journey into the darkness of the searching mind. The quest, much like the quest for the Holy Grail, leads to the ideal of art, symbolized by the palette that concludes this passage.

8, En Sof: When the Rhine flooded the family house where Anselm Kiefer grew up, it was the literary myths of Germany that spread into the basement. But the Rhine was also the border, the one the future artist gazed upon and that expanded during the river’s overflow: “You could see the lights on the other bank. The land that stretched beyond was not like any other land for the child who couldn’t cross to the other side; it was a promise of the future, a hope, it was the promised land.” In the very large photograph on lead representing the river, his silhouette appears from behind, following the code of German Romanticism, contemplating the opposite shore. It is his role as an artist that is at stake, and the work asserts: “When I speak of borders, I am speaking of our very essence… We are the membrane between the macrocosm and the microcosm, between the inside – what we are – and the outside, what we are as well… Art itself is a border, defined by the notion of a limit: it is always on the razor’s edge, on the threshold between mimicry and abstraction.” It’s understood how this thought, reaching out to the other territory, symbolizes the transmutation of art for which the artist bears responsibility. The transformation of life through art, of art itself through this electrolysis phenomenon, this exchange process between electricity, metal, and the mind. At this stage, the boundary between the foundational creations, such as photographs and paintings, books, or sculptures, has dissolved. Facing this work, almost minuscule, “En Sof” (Unlimited), the infinite that, by concentrating, made room for the world: creation.

Photo: Anselm Kiefer, Sonnenblumen (Sunflowers), 1994-2012. Tinted silver photographic print under glass in a steel frame; 103.5 x 160.5 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat

Info: Curators: Jean de Loisv and Grégoire Prangé, LaM (Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut), 1 allée du Musée, Villeneuve d’Ascq, France, Duration: 6/10/2023-3/3/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.musee-lam.fr/

![Anselm Kiefer, Heroische Sinnbilder, [Heroic symbols], 1969-2010, Black and white photographs, gouache, watercolor on paper and graphite on bound cardboard, 10 pages, 60 × 45 × 4 cm © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Atelier Anselm Kiefer](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/09-7.jpg)

Right: Anselm Kiefer, Ohne Titel, (Untitled), 1969-2009. Gouache on photograph; 110.5 x 86 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

![Anselm Kiefer, Am Anfang, [In the Beginning], 2008. Painting Oil, emulsion, lead and photography on canvas; 380 x 560 cm, Grothe Collection at the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Charles Duprat](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/04-16.jpg)

![Anselm Kiefer, Der Rhein [The Rhine], 1969-2012, Electrolysis on photographic print mounted on lead, 380 × 1,100 cm © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/07-8.jpg)

Right: Anselm Kiefer, Calmly Unendingly Moves (für J.J.), 2023. Glass, steel, lead photography and mixed media; 385 x 145 x 145 cm. © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet