TRACES: Robert Irwin

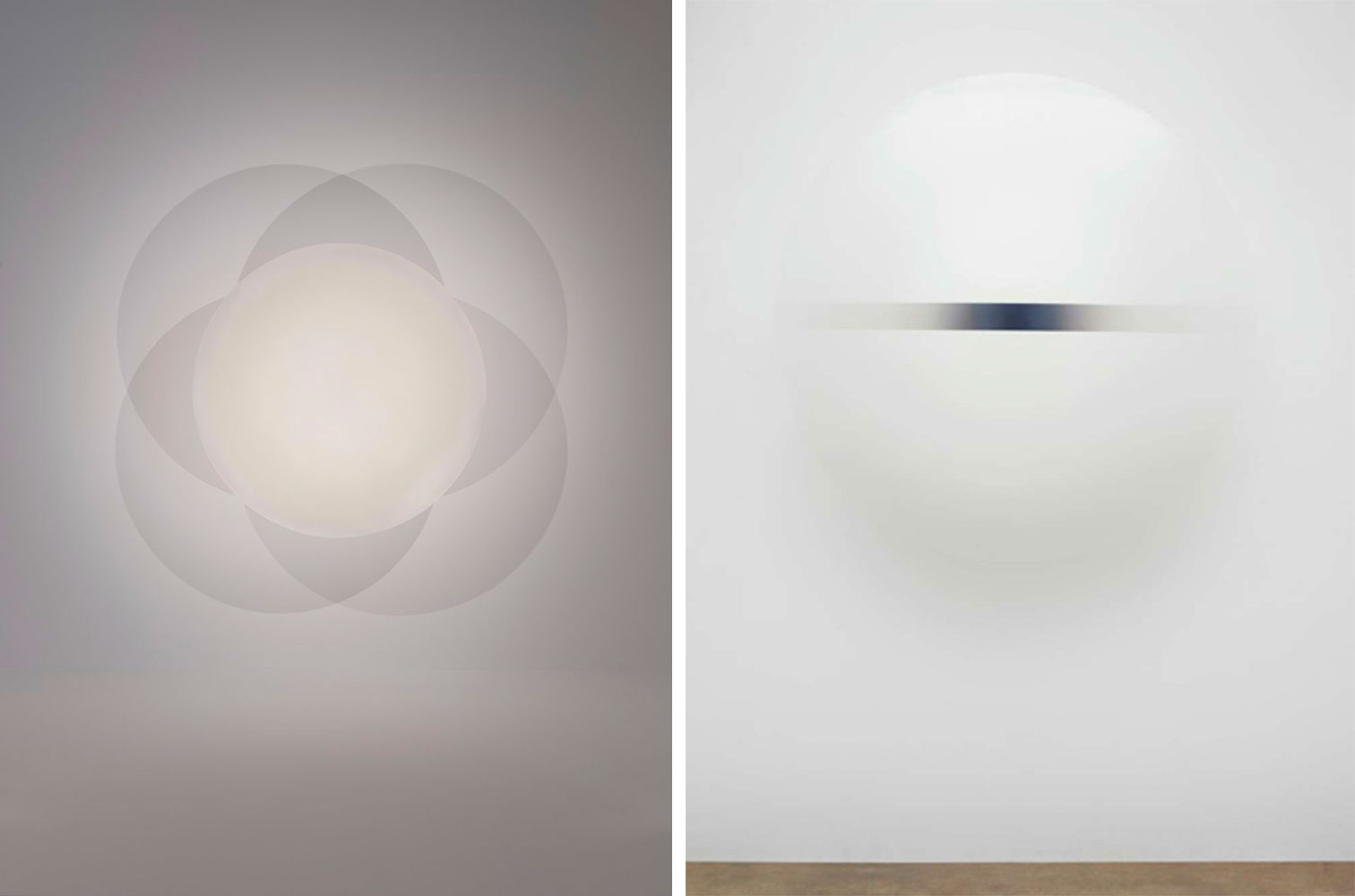

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Robert Irwin (12/9/1928-25/10/2023), his practice, which is often associated with the California-based Light and Space movement, encompasses painting and sculpture, installations, landscape projects, and interventions in public space. His actual medium is the viewer’s perception itself. The artist’s works dissolve conventional modes of reception to enable new forms of individual experience and an awareness of the aesthetic potential of our everyday surroundings. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Robert Irwin (12/9/1928-25/10/2023), his practice, which is often associated with the California-based Light and Space movement, encompasses painting and sculpture, installations, landscape projects, and interventions in public space. His actual medium is the viewer’s perception itself. The artist’s works dissolve conventional modes of reception to enable new forms of individual experience and an awareness of the aesthetic potential of our everyday surroundings. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

Robert W. Irwin was born in Long Beach, California, after serving in the United States Army from 1946 to 1947, he attended several art institutes: Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1948 to 1950, Jepson Art Institute in 1951, and Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1952 to 1954. He spent the next two years living in Europe and North Africa. Between the years 1957–1958, he taught at the Chouinard Art Institute. Irwin started his career as a painter in the 1950s. Though considered a defining figure of West Coast Abstract Expressionism, his focus was less the actual painting than the charged realm of experience that comes in to play between painting and viewer. Irwin’s interest in the phenomenological experience of art soon led him away from the gestural language favored by his colleagues and toward a radically reduced visual vocabulary of color fields and stripes. Irwin had his first monographic exhibition at Felix Landau Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1957, then moving to the newly founded Ferus Gallery, where he began exhibiting in 1958. By the early sixties, Irwin shifted to creating more restrained works with his line paintings, guided principally by questions of structure, color, and perception, and his dot paintings, works on gently bowed supports composed with small dots of near-complementary colors. In 1966, Irwin initiated a series of curved aluminum and acrylic discs that he painted and displayed with an arm extending out from the wall, creating a viewing experience that is impossible for a work on canvas. In the 1970s, Irwin abandoned painting and studio work altogether and developed a kind of installation art devoted entirely to the phenomenology of perception. His early interventions—made with such modest materials as scrim, twine or adhesive tape—probe the aesthetic potential of exhibition spaces by dismantling familiar patterns of perception and directing viewers’ attention to environmental qualities that already exist in a given space. From that basis, the artist radicalized his philosophy of aesthetic experience (ideas also reflected in Irwin’s many theoretical essays and lectures) and built a practice that consistently conceives of art as a response to the perceptual conditions of a specific site, whether spatial, cultural, historical or institutional. The resulting works could engage with the particular shape of an exhibition space in a museum, a quality of the light in the treetops of a park, a city view from a window or one of waves breaking over the Pacific Ocean. Some of Irwin’s interventions are of an almost inconspicuous, architectural nature. Others consist in installations employing such materials as fluorescent light tubes, semi-transparent Plexiglas walls, wire-and-steel constructions or colored aluminum panels. Some involve designing entire gardens. His work subverts the dominant logics of space and architecture by recalibrating the viewer’s physical and sensual experience, altering public space and creating surprising patterns of movement. Works in this vein include his legendary Central Garden (1997) at the Getty Center in Los Angeles; his installation Excursus: Homage to the Square³ (1998) at the Dia Art Foundation in New York (reimagined at Dia:Beacon in 2015). Irwin’s large-scale permanent installation Untitled (dawn to dusk) opened in July 2016 at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, occupying the site of a dilapidated former hospital building measuring approximately 10,000 square feet. Irwin designed the courtyard and divided the building’s interior into two halves—making one wing dark and the other light. With regularly spaced windows and scrims bisecting each side, the installation orchestrates viewers’ perceptions of light, interior space, and the surrounding landscape. The project, which was in development for fifteen years, is the first free-standing structure devoted exclusively to Irwin’s work. Over the past decade, Irwin has returned to his studio, using it as an experimental space to develop sculptural works with florescent lights and acrylic, such as his Sculpture/Configuration works exhibited at Pace in New York (2018), while continuing to develop his site-conditioned installations. Besides his installation work, Irwin wrote theory (Being and Circumstance: Notes Toward a Conditional Art, 1985) and generated landscape projects, notably the Central Garden at the Getty Center in Los Angeles (opened to the public in 1997). Irwin was also instrumental to the interior and landscape design of the Dia:Beacon contemporary art museum in Beacon, New York (opened 2003), which is housed in a former Nabisco box-printing factory.

Robert W. Irwin was born in Long Beach, California, after serving in the United States Army from 1946 to 1947, he attended several art institutes: Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1948 to 1950, Jepson Art Institute in 1951, and Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1952 to 1954. He spent the next two years living in Europe and North Africa. Between the years 1957–1958, he taught at the Chouinard Art Institute. Irwin started his career as a painter in the 1950s. Though considered a defining figure of West Coast Abstract Expressionism, his focus was less the actual painting than the charged realm of experience that comes in to play between painting and viewer. Irwin’s interest in the phenomenological experience of art soon led him away from the gestural language favored by his colleagues and toward a radically reduced visual vocabulary of color fields and stripes. Irwin had his first monographic exhibition at Felix Landau Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1957, then moving to the newly founded Ferus Gallery, where he began exhibiting in 1958. By the early sixties, Irwin shifted to creating more restrained works with his line paintings, guided principally by questions of structure, color, and perception, and his dot paintings, works on gently bowed supports composed with small dots of near-complementary colors. In 1966, Irwin initiated a series of curved aluminum and acrylic discs that he painted and displayed with an arm extending out from the wall, creating a viewing experience that is impossible for a work on canvas. In the 1970s, Irwin abandoned painting and studio work altogether and developed a kind of installation art devoted entirely to the phenomenology of perception. His early interventions—made with such modest materials as scrim, twine or adhesive tape—probe the aesthetic potential of exhibition spaces by dismantling familiar patterns of perception and directing viewers’ attention to environmental qualities that already exist in a given space. From that basis, the artist radicalized his philosophy of aesthetic experience (ideas also reflected in Irwin’s many theoretical essays and lectures) and built a practice that consistently conceives of art as a response to the perceptual conditions of a specific site, whether spatial, cultural, historical or institutional. The resulting works could engage with the particular shape of an exhibition space in a museum, a quality of the light in the treetops of a park, a city view from a window or one of waves breaking over the Pacific Ocean. Some of Irwin’s interventions are of an almost inconspicuous, architectural nature. Others consist in installations employing such materials as fluorescent light tubes, semi-transparent Plexiglas walls, wire-and-steel constructions or colored aluminum panels. Some involve designing entire gardens. His work subverts the dominant logics of space and architecture by recalibrating the viewer’s physical and sensual experience, altering public space and creating surprising patterns of movement. Works in this vein include his legendary Central Garden (1997) at the Getty Center in Los Angeles; his installation Excursus: Homage to the Square³ (1998) at the Dia Art Foundation in New York (reimagined at Dia:Beacon in 2015). Irwin’s large-scale permanent installation Untitled (dawn to dusk) opened in July 2016 at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, occupying the site of a dilapidated former hospital building measuring approximately 10,000 square feet. Irwin designed the courtyard and divided the building’s interior into two halves—making one wing dark and the other light. With regularly spaced windows and scrims bisecting each side, the installation orchestrates viewers’ perceptions of light, interior space, and the surrounding landscape. The project, which was in development for fifteen years, is the first free-standing structure devoted exclusively to Irwin’s work. Over the past decade, Irwin has returned to his studio, using it as an experimental space to develop sculptural works with florescent lights and acrylic, such as his Sculpture/Configuration works exhibited at Pace in New York (2018), while continuing to develop his site-conditioned installations. Besides his installation work, Irwin wrote theory (Being and Circumstance: Notes Toward a Conditional Art, 1985) and generated landscape projects, notably the Central Garden at the Getty Center in Los Angeles (opened to the public in 1997). Irwin was also instrumental to the interior and landscape design of the Dia:Beacon contemporary art museum in Beacon, New York (opened 2003), which is housed in a former Nabisco box-printing factory.