PRESENTATION: Paraventi-Folding Screens from the 17th to 21st Centuries

The exhibition “Paraventi: Folding Screens from the 17th to 21st Centuries” explores the histories and semantics of these objects by tracing trajectories of cross-pollination between East and West, processes of hybridization between different art forms and functions, collaborative relationships between designers and artists, and the emergence of newly created works. The folding screens embody liminality and the idea of being on the threshold of two conditions, literally and metaphorically. They cross barriers between different disciplines, cultures, and worlds.

The exhibition “Paraventi: Folding Screens from the 17th to 21st Centuries” explores the histories and semantics of these objects by tracing trajectories of cross-pollination between East and West, processes of hybridization between different art forms and functions, collaborative relationships between designers and artists, and the emergence of newly created works. The folding screens embody liminality and the idea of being on the threshold of two conditions, literally and metaphorically. They cross barriers between different disciplines, cultures, and worlds.

By Dimitris Lempesis

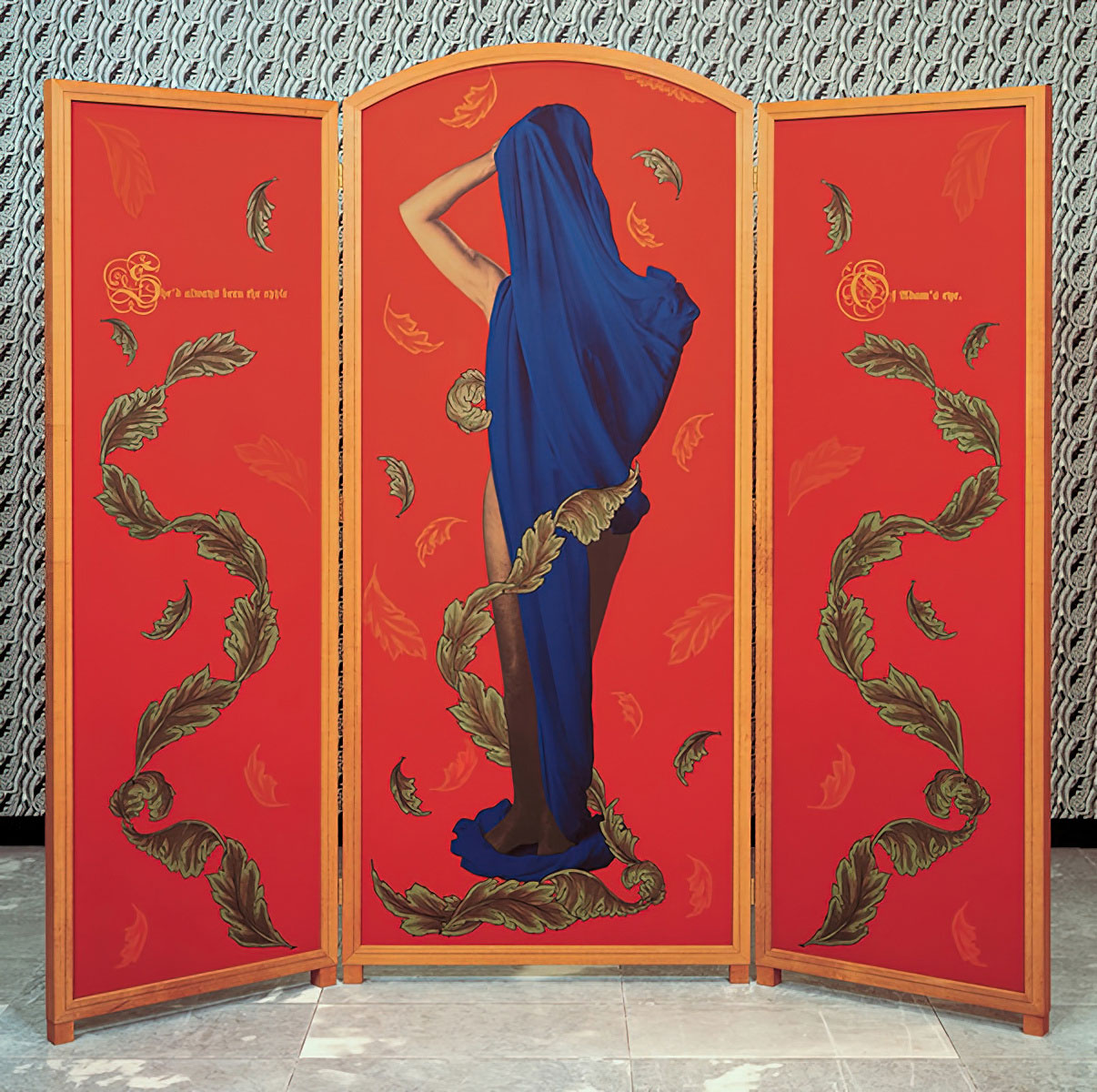

Photo: Fondazione Prada Archive

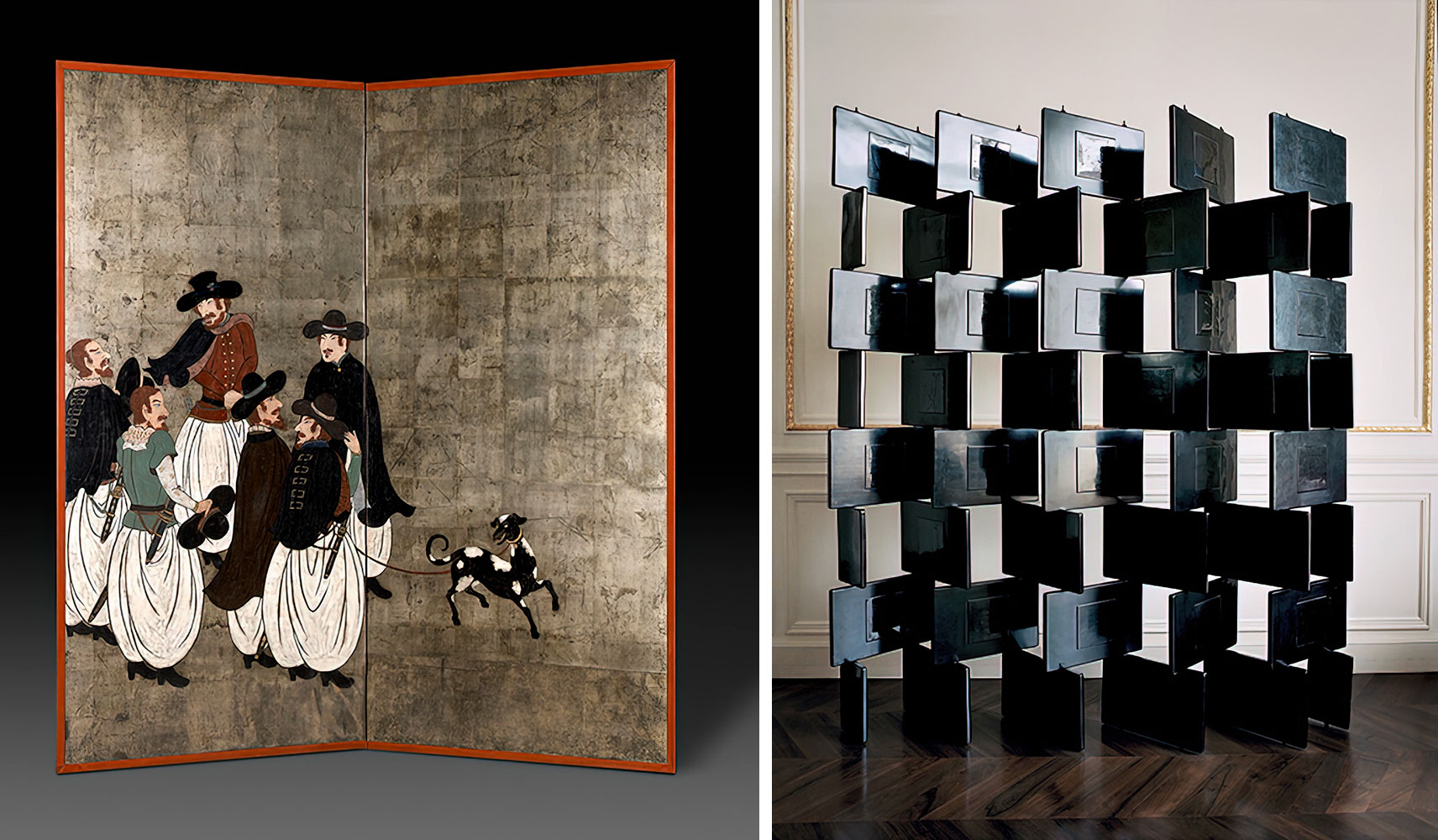

The innovative exhibition “Paraventi: Folding Screens from the 17th to 21st Centuries”, examines the many questions and paradoxes surrounding the unfolding history of the paravent. This history of the folding screen is one of cultural migration (from East to West), hybridization (between both different art forms and functions) and of what is concealed and revealed. As we shall explore, this history, and especially the way it manifests in the present, is one of liminal objects and of liminality itself; in the process collapsing the rigid distinctions and hierarchies between the different disciplines of art and architecture, decoration, and design. The exhibition gathers more than seventy folding screens, including valuable historical objects and more recent works on loan from international museums and private collections, and a selection of new creations commissioned from more than fifteen international artists specifically for this project. On the Podium’s ground floor, curved transparent Plexiglas partitions alternating with sinuous curtains will simulate the shapes of these objects. They create a series of spaces with different light atmospheres, in which visitors will be confronted with each thematic group and connected in continuity in a fluid path, throughout the transparency of the partitions. On the upper floor, the single exhibition space represents the overall history of the screens, which are arranged in chronological order on shaped pedestals, that emphasize the typical paravents shape, in a nod to innovative museological displays such as Lina Bo Bardi’s MASP in São Paulo and indeed SANAA’s work for Louvre-Lens. On the Podium’s ground floor, an introductory section combines three 17th- and 18th-century Chinese and Japanese screens depicting naval battles and aerial views to investigate these objects’ inherent ambiguity and transnational nature. It focuses on their possible dual reading from an Eastern right-to-left or Western left-to-right perspective, as landscape or cartography. The second sequence explores the theme of representing the seasons and temporal narratives in a spatial dimension by juxtaposing a folding screen by Chinese artist Chen Zhifo, a master of gongbi* paintings in the 20th century that meticulously depicted realistic birds and flowers, with a more abstract and ironic one created by American artist Jim Dine in 1969 and titled Landscape Screen (Sky, Sun, Grass, Snow, Rainbow). With a group of recent and new works by Tony Cokes, Cao Fei, Shuang Li, Joan Jonas, Tiffany Sia, and Wu Tsang, the exhibition also addresses how a seemingly timeless object such as a folding screen can become a medium for projecting a layering of images and multiscreen effects with the pervasive use of digital technologies. Another section delves into one of the functions of the screen, namely to conceal, protect and thus create an intimate, private and secret dimension within the domestic environment. Historical works such as the Three-fold Screen with embroidered panels depicting heroines (The Legend of the Good Women) (c.1860) by William Morris and Elizabeth Burden and Konku (1982) by William N. Copley are associated with contemporary screens by artists such as Lisa Brice, Anthea Hamilton, Lorna Simpson, and Carrie Mae Weems, who through an alternative gaze introduce themes such as seduction and shame. Queer aesthetics are at the center of another series of works that transform this everyday object into an overtly subversive decoration element. From an Omega workshop screen by Duncan Grant from the Bloomsbury haven of Charleston to a rare 1929 screen made by Francis Bacon and World of Cats (1966) by British actor, writer, and collagist Kenneth Halliwell through to works by contemporary artists such as Kai Althoff, Marc-Camille Chaimowicz and Francesco Vezzoli, a culturally disruptive narrative is told. It should not be forgotten that screens can also be powerful tools of political propaganda, display of strength and wealth, ostentation and construction of narratives capable of affecting history. Examples are the monumental work dating back to 1718 by Pedro de Villegas, consisting of ten elements that feature an account of the Conquest of Mexico by the leader Hernán Cortés on one side, while the back shows a decoration with Eastern scenes, and the new commission given to Goshka Macuga that addresses the theme of the transmission of knowledge and culture. The last group of works set up on the Podium’s ground floor explores the paradox of transparency through conceptual or humorous negations of the practical function of these objects. The transparent folding screens by Carla Accardi and Isa Genzken frame the surrounding environment rather than concealing it. They open new perspectives and suggest new visions rather than circumscribing a space. In contrast to the synchronic approach adopted on the ground floor, the upper floor deliberately follows a diachronic logic. The chronological sequence makes it possible to reconstruct the historical evolution of this art and decorative object, from its Eastern origins and reciprocal dialogues with the Western traditions to the innovative contribution made by 20th- and 21st-century designers and artists. Chinese and Japanese screens ranging from the 17th to the 19th century paved the way for a series of transformations and metamorphoses that includes here, among others, the applications of design and architectural masters such as Alvar Aalto, Charles and Ray Eames, Le Corbusier, Josef Hoffmann, and Jean Prouvé, the avant-garde experiments of Giacomo Balla, René Magritte, and Pablo Picasso, and the creations of contemporary artists such as Marlene Dumas, Mona Hatoum, Yves Klein, Sol LeWitt, Betye Saar, Keiichi Tanaami, Cy Twombly, and Luc Tuymans, and younger artists like Kamrooz Aram, Atelier E.B (Beca Lipscombe & Lucy McKenzie), and Małgorzata Mirga-Tas.

*Gongbi is a careful realist technique in Chinese painting, the opposite of the interpretive and freely expressive xieyi style. The name is from the Chinese gong jin meaning ‘tidy’ (meticulous brush craftsmanship). The gongbi technique uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimits details very precisely and without independent or expressive variation. It is often highly colored and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects.

Works by: Alvar Aalto, Carla Accardi, Kai Althoff, Kamrooz Aram, Atelier E.B (Beca Lipscombe & Lucy McKenzie), Francis Bacon, Giacomo Balla, Hernan Bas, Lisa Brice, Elizabeth Burden and William Morris, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Tony Cokes, William N. Copley, Pedro de Villegas, Jim Dine, Marlene Dumas, Charles & Ray Eames, Elmgreen & Dragset, Cao Fei, Isa Genzken, Duncan Grant, Eileen Gray, Wade Guyton, Kenneth Halliwell, Anthea Hamilton, Mona Hatoum, David Hockney, Josef Hoffmann, Pierre Jeanneret, Joan Jonas, William Kentridge, Yves Klein, Le Corbusier, Sol LeWitt, Shuang Li, Goshka Macuga, René Magritte, Kerry James Marshall, Takesada Matsutani, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Chris Ofili, Laura Owens, Lê Phổ, Pablo Picasso, Jean Prouvé, Man Ray, Betye Saar, Watanabe Shikō, Tiffany Sia, Lorna Simpson, John Stezaker, Keiichi Tanaami, Wu Tsang, Luc Tuymans, Cy Twombly, Francesco Vezzoli, Carrie Mae Weems, Franz West, T. J. Wilcox, Chen Zhifo.

Photo: Mona Hatoum, Grater Divide, 2002, Mild Steel. 204 cm x variable width and depth, © Mona Hatoum Courtesy White Cube (Photo: Iain Dickens)

Info; Curator: Nicholas Cullinan, Fondazione Prada, Largo Isarco 2, Milan, Italy, Duration: 26/10/2023-22/2/2024, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.fondazioneprada.org/

Right: Eileen Gray, ‘Brick’ Screen, c. 1925, Lacquered wood, with steel rods. 213 x 178 x 2 cm, Joe and Marie Donnelly Collection, Paris Photo: François Halard. Courtesy J&M Donnelly