PRESENTATION: Fragments of a Faith Forgotten-The Art of Harry Smith Harry Smith, Part II

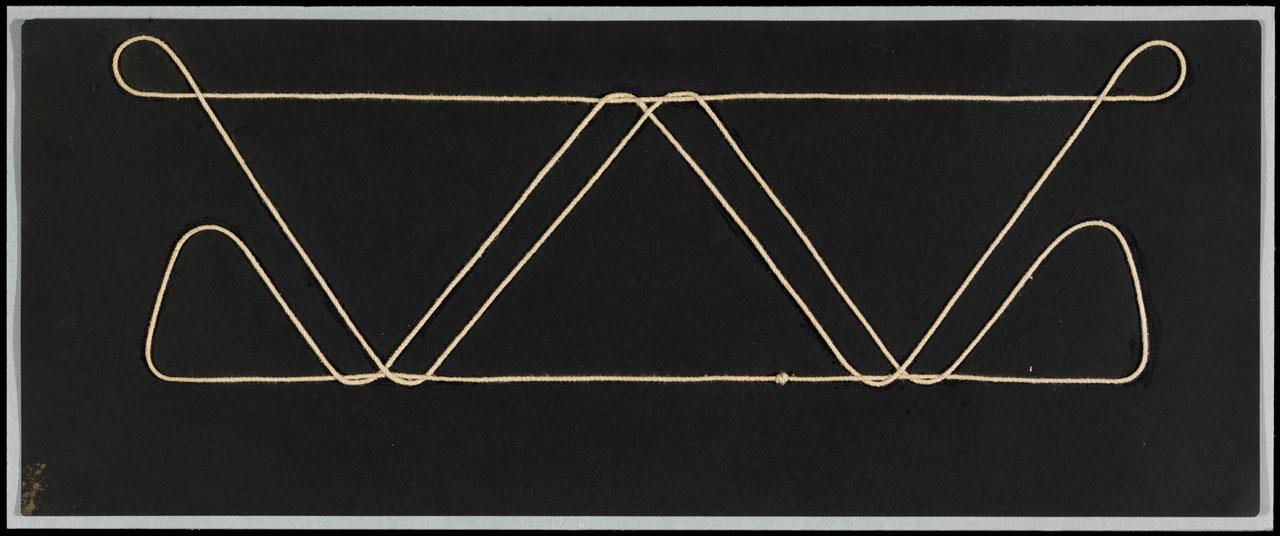

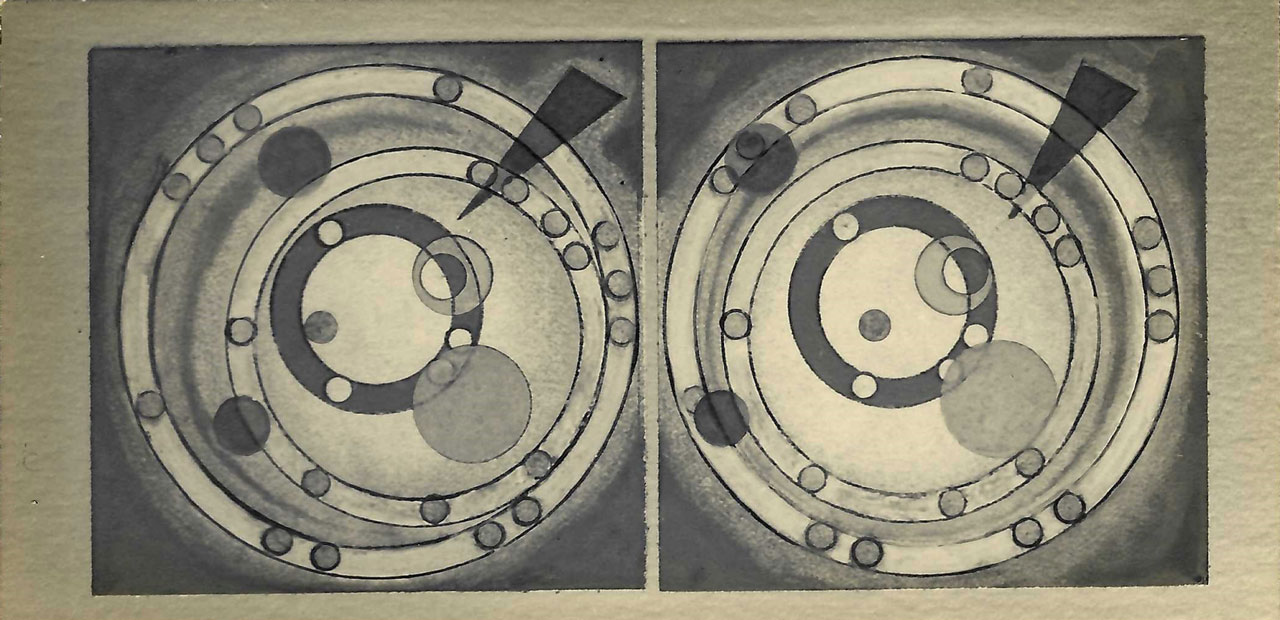

![Harry Smith, Ko Ko [Jazz Painting], c. 1949–51. Lightbox projection from 35mm slide of lost original painting, 21 7/8 × 29 in. (55.6 × 73.7 cm). Estate of Jordan Belson](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/00-24.jpg) Harry Smith, was a painter, filmmaker, folklorist, musicologist, and collector as well as a radical nonconformist whose work defies categorization. Although his creative output includes paintings, films, poetry, music, and sound recordings, it also consists of extensive collections of overlooked yet revealing objects, such as string figures and found paper airplanes. His best-known work, a compilation of recordings from the 1920s and 1930s titled the Anthology of American Folk Music, achieved cultlike status among many musicians and listeners since it was first published in 1952.

Harry Smith, was a painter, filmmaker, folklorist, musicologist, and collector as well as a radical nonconformist whose work defies categorization. Although his creative output includes paintings, films, poetry, music, and sound recordings, it also consists of extensive collections of overlooked yet revealing objects, such as string figures and found paper airplanes. His best-known work, a compilation of recordings from the 1920s and 1930s titled the Anthology of American Folk Music, achieved cultlike status among many musicians and listeners since it was first published in 1952.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Whitney Museum of American Art Archive

The exhibition “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith” puts the artist’s life on display alongside his art and collections. It follows him from an isolated Depression-era childhood in the Pacific Northwest, a time when he was immersed in ecstatic religious philosophies and Native American ceremony, to his bohemian youth of marijuana, peyote, and intellectualism in postwar Berkeley, California. The exhibition also traces his path through the milieus of bebop and experimental cinema in San Francisco to his decades in New York, where he was an essential part of the city’s avant-garde fringe. Keenly attuned to changing technology, Smith embraced innovation and used whatever was new and of the moment. At the same time, his lifelong interest in abstract art, ancient traditions, metaphysics, spiritualism, folk art, and world music came to the fore even as he devised ingenious ways of collecting sounds and creating films. These concerns make Smith’s work feel increasingly prescient as collecting and sharing come into view as creative acts that are necessary for drawing meaning from the glut of images and juxtaposition of cultures we encounter every day. Harry Smith’s lifelong research, recording, and collecting practices began when he was fifteen years old and living in the Pacific Northwest, where his mother worked on the Lummi reservation as a teacher. During his teenage years, he frequently visited the Lummi and Swinomish people, both original inhabitants of what is now Washington State. While there, he documented songs, ceremonies, languages, and artistic traditions through photography, painting, sound recording, and his own form of notation. Presaging his later practice of adapting available technology to suit his needs, Smith wired an acetate-disc recorder with a battery in order to make high-quality recordings. From a contemporary perspective, understanding even a teenage Smith’s time spent with the Lummi and Swinomish people seems to require us to hold two contradictory visions of it simultaneously. On the one hand, anthropology as a field first took hold near Smith’s childhood home—and early on the discipline was fundamentally extractive, driven by claims that it had to salvage Indigenous cultures that it framed as disappearing. In this way, anthropology reinforced the violence of settler colonialism within the United States, and the shadow of this history hangs over Smith’s research. On the other hand, it seems that Smith, who was self-taught in his anthropological studies, did not share all of the discipline’s assumptions and methods. His early work was the portal to his study of patterns of belief and lexicons of representation. Smith would continue his study of Indigenous people over the course of his life, recording the peyote ritual songs of the Kiowa people and collecting the geometric patchwork patterns of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. Lured to Berkeley in late 1945 in the hope of continuing his anthropological studies, Smith was quickly drawn into the vibrant Bohemian scene of the Bay Area. Within a few years he had relocated to San Francisco’s Fillmore District, which had emerged as a center of African American life and culture following the removal and incarceration of its Japanese population during the Second World War. In the Fillmore, Smith forged close connections with musicians and frequented jazz clubs, including San Francisco’s important nightclub Jimbo’s Bop City, where he painted large abstract murals on the walls. At the same time, he applied his notational genius, combined with inspiration from psychedelic drugs, to the execution of a series of deliriously intense, quasi-abstract paintings intended to represent new recordings by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. These paintings’ elaborate and sinuous forms directly correspond to each phrase and note of the music. Now lost, the paintings can only be seen on color slides. The highly influential multivolume “Anthology of American Folk Music”, first released by Folkways Records in 1952, marks Smith’s unparalleled efforts to preserve American song as both art and artifact. As Smith would later reflect: “The whole anthology was a collage. I thought of it as an art object.” As a recent arrival in New York and in need of money, Smith tried to sell Moses Asch, the owner of Folkways Records, part of his extensive record collection. Asch instead encouraged him to produce a compilation, which resulted in the “Anthology of American Folk Music”. Smith divided the work into three sets of two LPs: “Ballads,” “Social Music,” and “Songs”— and accompanied each with an illustrated booklet of notes. In these notes, Smith used language that was common at the time, describing songs for the African American market as “race music” and as “hillbilly” or “old-time” for the Southern white listeners and Northerners with roots in the South. The eighty-four songs on the anthology were made between 1927, when electric recordings made accurate music reproduction possible, and 1932, when the Great Depression halted folk music sales. Smith included songs that displayed distinct regional qualities, both rhythmic and verbal, and were originally intended for local rather than national audiences. A pivotal influence during the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, Smith’s anthology inspired Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, and Pete Seeger, among others. In 1991, Smith received a lifetime achievement award at the Grammys for his preservation and promotion of folk music. After receiving the award, Smith noted: “My dreams came true. I saw America changed through music.”

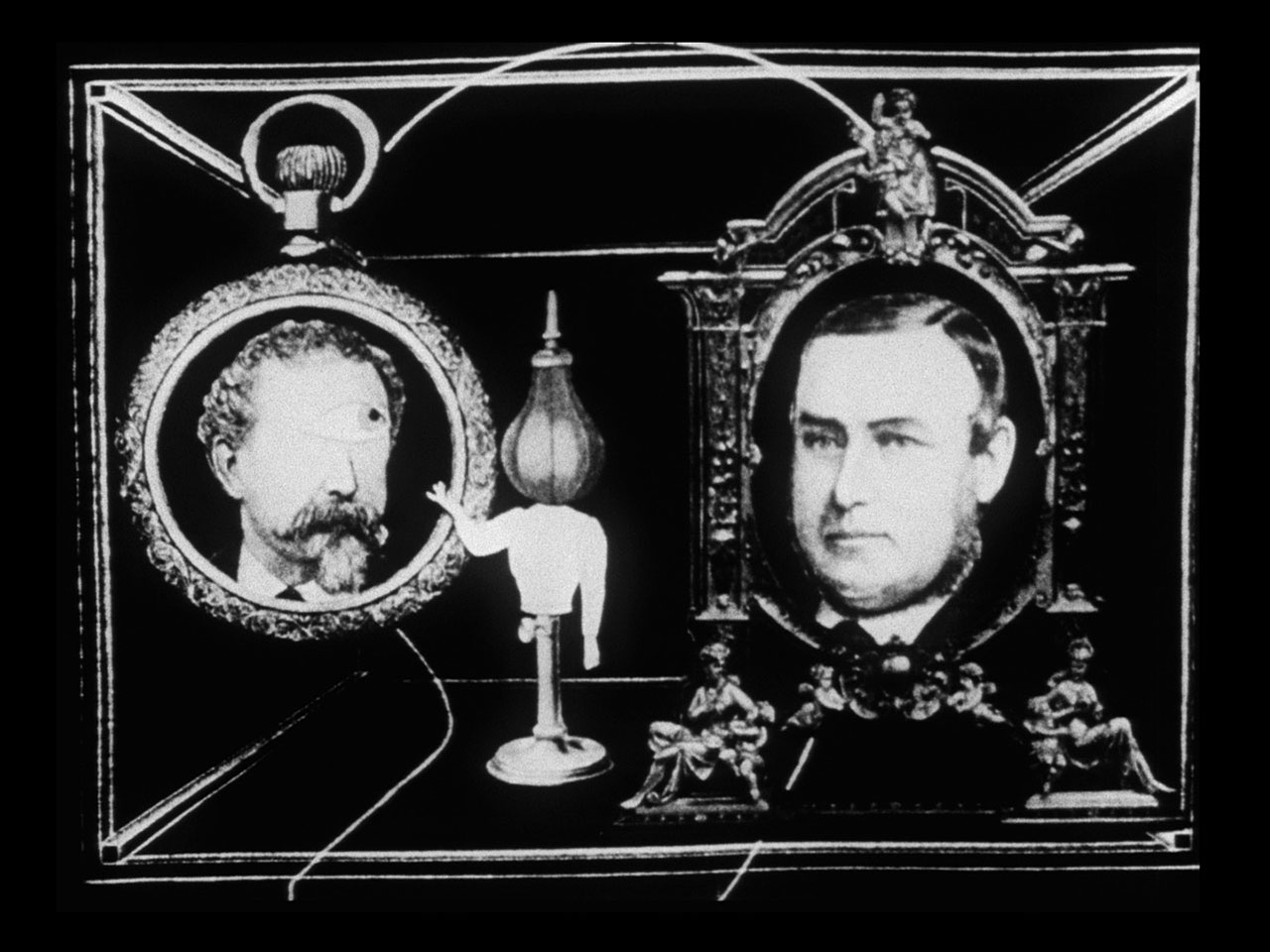

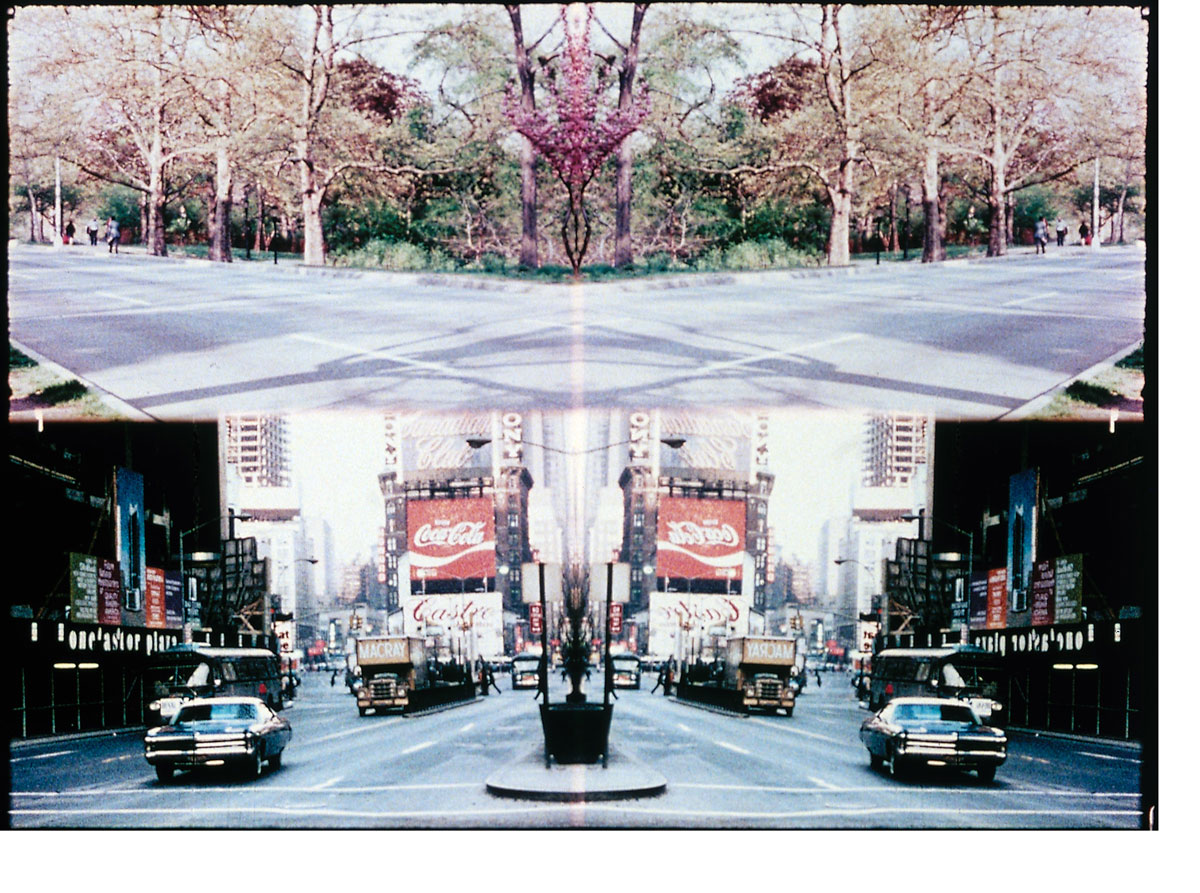

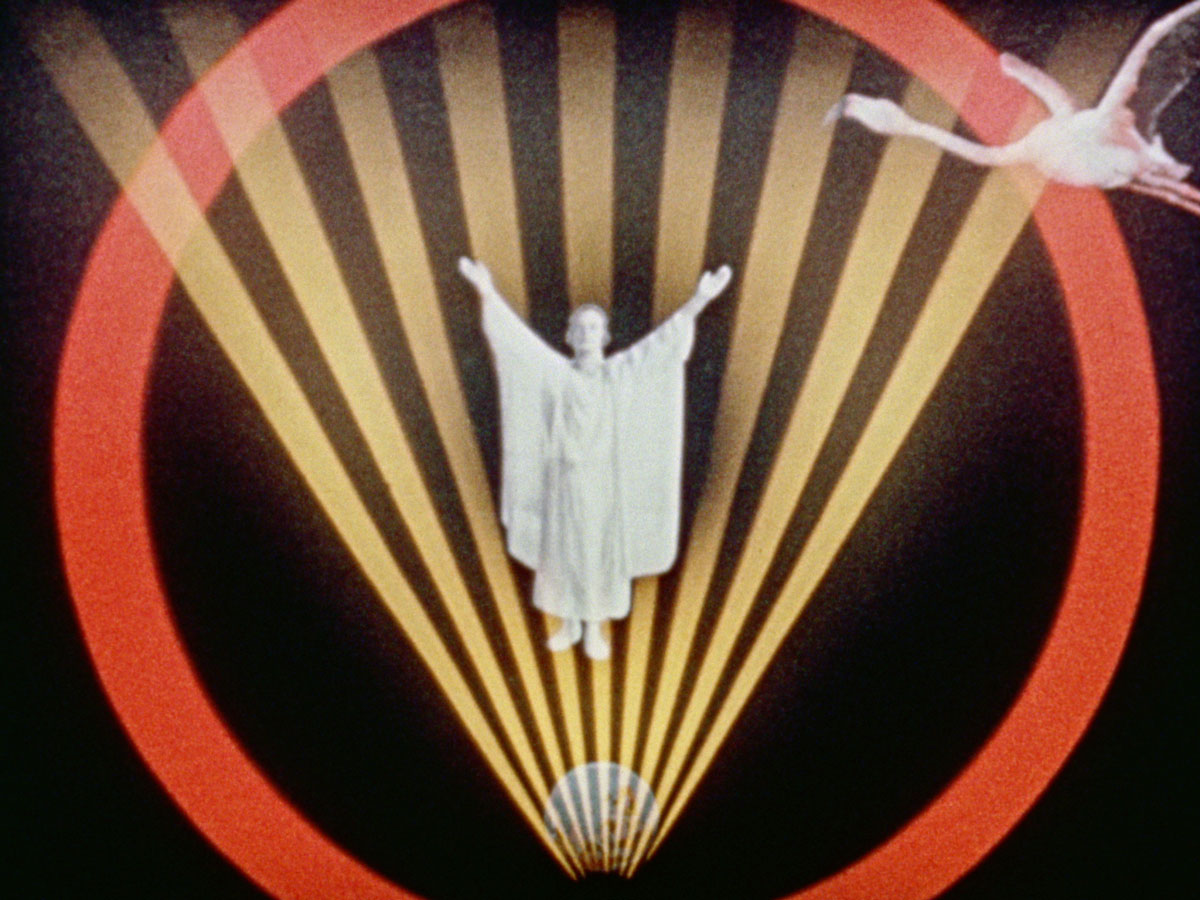

By 1957 Smith had finished his first eight films, a body of work that came to be known as Early Abstractions. The first films were meticulously hand crafted and painted, then optically printed. Working frame by frame, Smith devised a range of techniques to apply layers of paint, stencils or cut out shapes to reveal movement across a two – dimensional plane. A series of short films numbered and strung together, the Early Abstractions ranged from geometric patterns in black, white and color, to complex collages revolving around a surrealistic barrage of disparate esoteric imagery culled from various texts. The range of techniques and styles in his forty years of output is astounding, each film builds on the previous, with the subject matter and techniques increasing in complexity. “Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic Feature” animates cutouts from nineteenth-century books and department store catalogs—Victoriana that carried an air of nostalgia not only for Smith but also for Surrealists like Max Ernst. He relied on stop motion animation to activate these cutouts, resulting in a new and experimental approach to imagery and storytelling that was dreamlike and spiritual. The film depicts a woman’s dental procedure, her subsequent ascension to heaven, and finally her return to earth. By combining disparate influences—the Kabbalah and his own epilepsy research at the Montreal Neurological Institute—Smith portrays the kingdom of heaven as a mix of Israel and Montreal. Smith realized “Film No. 12” only in part; he intended the sixty-six minutes to constitute the opening sequences of a substantially longer work. At times, Smith modified the film when it was projected by adding framing slides and colored projection gels. Smith’s use of a Rubin’s vase—a vase with negative spaces that form the illusion of two facing profiles—in “Film No. 12” was the inspiration for the architectural form near the center of the exhibition. Smith’s epic film “Mahagonny” (1970–80) is a four-screen translation of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s 1930 opera “Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny”, a political satire set in an imaginary American metropolis that prioritizes indulgence over lawfulness and concludes with the city’s total destruction. Shot from 1970 to 1972 and edited by Smith for eight years, the film pairs the opera’s score with four categories of images—people or portraits (P), animation (A), scene or symbols (S), and nature (N)—that appear on screen in the following order: P.A.S.A.P.A.S.N.A.P.A.S.A.P.A.N.S.A.P.A.S.A.P.N. Most of the film was shot in the Chelsea Hotel, where Smith lived from 1968 to 1977, and features notable avant-garde figures such as poet Allen Ginsberg, filmmaker Jonas Mekas, and musician Patti Smith. These appearances are intercut with shots of New York landmarks, works from Robert Mapplethorpe’s studio, and Smith’s own animations. The film merges scenes from Smith’s life and work with recognizable symbols of nature and humanity that he intended to be universally accessible. Originally composed of a grid of four 16mm-images, the film was redesigned by Smith as a multiscreen projection to allow for fanciful modes of display. One of those—a boxing ring that echoes the original set of Weill and Brecht’s opera—is referenced in the exhibition.

Photo: Harry Smith, Ko Ko [Jazz Painting], c. 1949–51. Lightbox projection from 35mm slide of lost original painting, 21 7/8 × 29 in. (55.6 × 73.7 cm). Estate of Jordan Belson

Info: Curators: Carol Bove; Dan Byers; Rani Singh; Elisabeth Sussman, Assistant Curators: Kelly Long, McClain Groff, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 4/10/2023-28/1/2024, Days & Hours: Mon, Wed-Thu & Sat-Sun 13:00-18:00, Fri 10:30-22:00, https://whitney.org/

![Harry Smith, Algo Bueno [Jazz Painting], c. 1948–49. Lightbox projection from 35mm slide of lost original painting, 27 7/8 x 28 in. (55.6 x 71.1 cm). Estate of Jordan Belson](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/02-11.jpg)

![Harry Smith, Untitled 3-D Greeting Card[“are you looking for the third dimension?”], 1953. Silkscreened ink on paper, 5 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. (14.6 cm x 14.6 cm). Estate of Jordan Belson](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/07-5.jpg)

![Left: Harry Smith, Untitled [Demoniac self-portrait], c. 1952. Scratchboard, 8, 1/2 x 5 1/2in. (21.6 x 14 cm). Lionel, Ziprin Archive, New YorkRight: Harry Smith, still from Film No. 14: Late, Superimpositions, 1964. 16mm film, restored to 35mm, transferred to digital video, color, sound; 31 min. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives, New York, NY; restored by Anthology Film Archives and the Film Foundation with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation © Anthology Film Archives and Harry Smith Archives](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/08a-2.jpg)

Right: Harry Smith, still from Film No. 14: Late, Superimpositions, 1964. 16mm film, restored to 35mm, transferred to digital video, color, sound; 31 min. Courtesy of Anthology Film Archives, New York, NY; restored by Anthology Film Archives and the Film Foundation with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation © Anthology Film Archives and Harry Smith Archives

![Left: Harry Smith, Untitled [Study for Inkweed, Studios greeting card], c. 1952. India ink on scratchboard, 8 x 6 in. (20 x 15 cm)., Private collection, Ziprin Archive, New YorkRight: Harry Smith, Untitled [Zodiacal hexagram scratchboard], c. 1952. Ink on cardstock, 7 x 5 1/2 in. (17.8 x 14 cm). Lionel Ziprin Archive, New York](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/09a.jpg)

Right: Harry Smith, Untitled [Zodiacal hexagram scratchboard], c. 1952. Ink on cardstock, 7 x 5 1/2 in. (17.8 x 14 cm). Lionel Ziprin Archive, New York