ART CITIES:Venice-Marcel Duchamp

As an artist who constantly challenged convention, Marcel Duchamp refused to respect the entrenched cultural and commercial hierarchies that extolled—even fetishized—artistic originals while dismissing reproductions of all sorts. “A duplicate or a mechanical repetition has the same value as the original,” he argued. Throughout his oeuvre, Duchamp exemplified the veracity of this assertion, proposing a new paradigm in the history of modern art, whereby certain copies and the originals from which they were replicated elicited comparable forms of aesthetic pleasure.

As an artist who constantly challenged convention, Marcel Duchamp refused to respect the entrenched cultural and commercial hierarchies that extolled—even fetishized—artistic originals while dismissing reproductions of all sorts. “A duplicate or a mechanical repetition has the same value as the original,” he argued. Throughout his oeuvre, Duchamp exemplified the veracity of this assertion, proposing a new paradigm in the history of modern art, whereby certain copies and the originals from which they were replicated elicited comparable forms of aesthetic pleasure.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: The Peggy Guggenheim Collection Archive

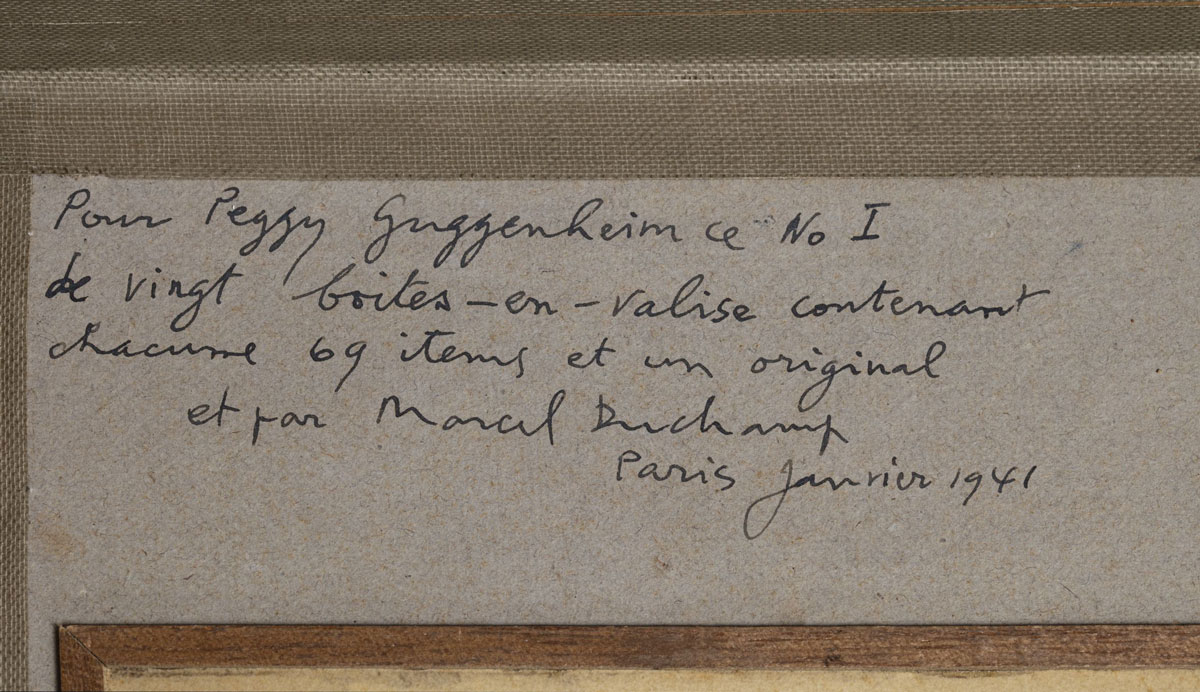

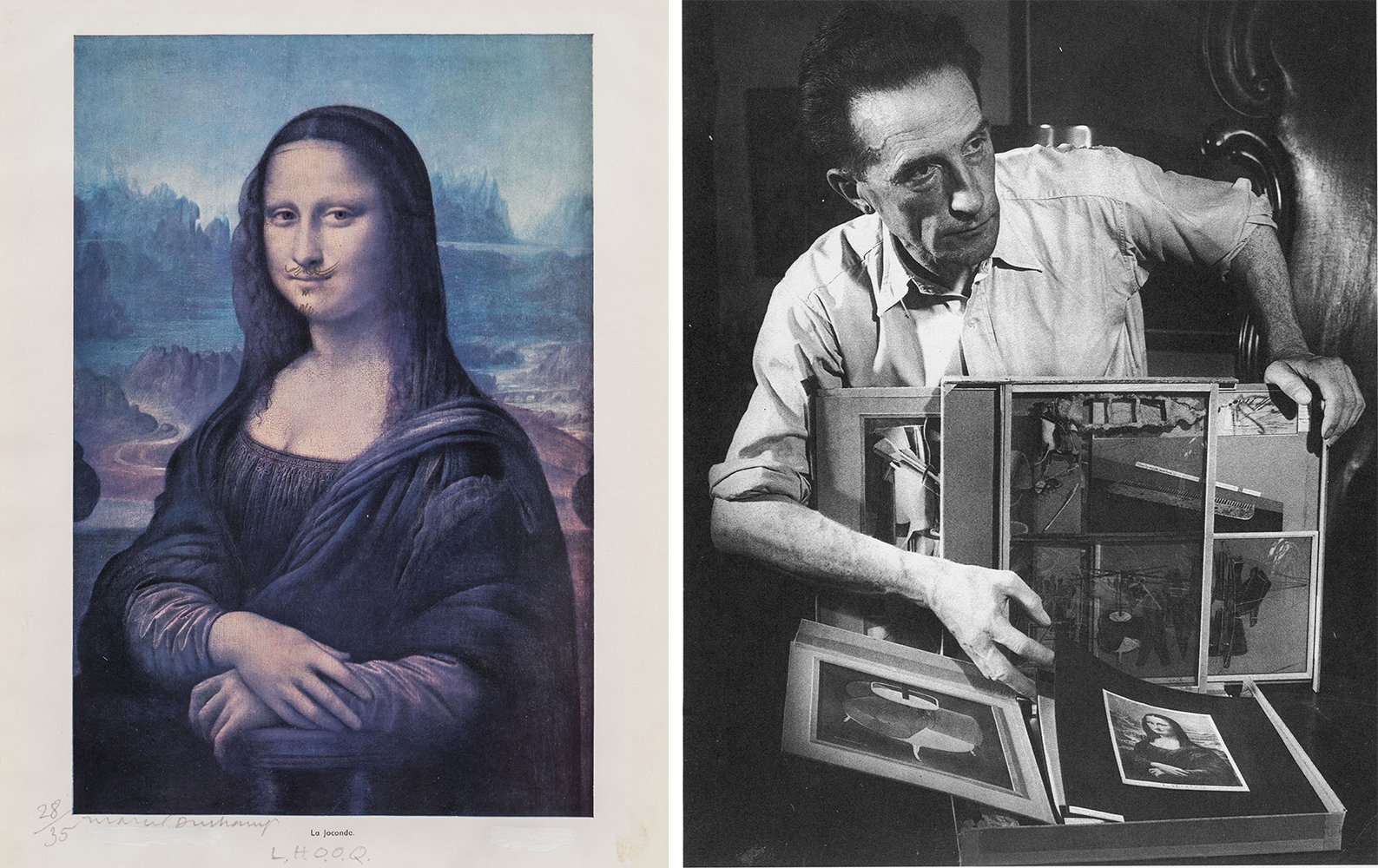

Marcel Duchamp and Peggy Guggenheim met in Paris around 1923. Beginning in autumn 1937, he became one of her most trusted mentors and advisors, as she set out to launch the art gallery Guggenheim Jeune, which opened in London on January 24, 1938, and soon after to build a collection of modern art. The exhibition “Marcel Duchamp and the Lure of the Copy” features some sixty artworks dating from 1911 to 1968. These include iconic objects from the permanent collection of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, such as “Nu (esquisse)”, jeune homme triste dans un train”, “Sad Young Man in a Train)” (1911–12) and “de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise) (1935–41), as well as from other Italian and U.S. institutions, including the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. The exhibition also presents several lesser-known artworks in private hands, including the artist’s estate. Furthermore, fully half of the works on display come from the distinguished Venetian collection of Attilio Codognato, who first took an interest in Duchamp’s work in the early 1970s. This is the first time that such a broad selection of Duchamp’s works in the Codognato collection is displayed in an exhibition. Despite having executed some of the most recognizable canvases of the 20th century, such as Nude”,” Sad Young Man in a Train” and “Le Roi et la reine entourés de nus vites” (1912), a masterpiece from the Philadelphia Museum of Art which is on view in the exhibition, Duchamp abandoned easel painting in 1918 at the age of thirty-one. For the next fifty years, he engaged in multiple creative acts, virtually none of which was considered high art at the time. In addition to those endeavors, he repeatedly reproduced his own work in different media and on various scales. These meticulously executed copies enabled him to disseminate his otherwise modest output without generating anything indisputably new. As a result, he also deftly circumvented the voracious art market. In reproducing his work in different media, on various scales, and in limited editions, Duchamp illustrated that certain duplicates and the originals from which they were replicated offered comparable forms of aesthetic pleasure. In so doing, Duchamp also redefined what constitutes a work of art and, by extension, the identity of the artist. Throughout his oeuvre, he continually called into question the traditional hierarchy between original and copy. For Duchamp, the ideas embodied in a work of art were of equal significance as the physical object itself. The importance that he accorded to aesthetic concepts inspired him to reproduce his own work repeatedly and with meticulous exactitude, beginning with the “Boîte de 1914” (1913–14/15), a series of photographic facsimiles of handwritten notes, and continuing into the 1960s, with replicas of his historic readymades. Examining the radically innovative and varied ways that Duchamp quoted himself over the course of his long career as an artist, the exhibition is organized in several interrelated sections: Origins, Originals, and Family Resemblances; Past Is Prologue; The Magic of Facsimiles; Authentic Copies; Disciplining and Emboldening the Hand; Cloning the Self, Clothing the Other; Hypnotic Repetition; and Themes and Variations. The exhibition centers on “Box in a Valise”, an innovative compilation of reproductions and miniature replicas of his creations, and no. I of the deluxe edition of twenty travelling suitcases—the earliest of which is marked Louis Vuitton—featuring an inscription dedicated to Peggy Guggenheim: “Pour Peggy Guggenheim ce No 1 de vingt boîtes-en-valise contenant chacune 69 items et unoriginal et par Marcel Duchamp Paris Janvier 1941.” “Box in a Valise” is Duchamp’s most compelling encapsulation of his passion for replication as a unique mode of creative expression. The last section of the show, titled Marcel Duchamp: Exploring the “Box in a Valise”, is a scientific exhibition organized by the Conservation Department of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence. This presents the results of a scientific study carried out in two stages, in 2019 and 2023, in the conservation and restoration laboratories of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure. A multimedia installation offers a fascinating and unique exploration of the world of conservation. Visitors can delve into the techniques and materials employed by the artist to create an icon of twentieth-century art, as well as the scientific investigation and analysis techniques used by conservators to better understand it, and the solutions they employed to ensure its best conservation. A video and a touchscreen offer visitors a chance to explore the “Box in a Valise”, both as a single unit, as the artist intended, as well as through each of the 69 elements contained inside it and the complex structure that displays them. Such an overview enables the viewer to grasp the astonishing scope of Duchamp’s lifelong preoccupation with replication as a distinct medium of artistic expression. It also illustrates the extent to which his whimsical, often-hybrid handiworks perturbed and at times totally eluded standard artistic classifications in use at the time of their conception. A section of the exhibition focuses on Duchamp and guidance Guggenheim’s close and enduring relationship: photographs, archival documents, and publications attest to the long friendship between them, two very different but equally colorful personalities. They also reveal the privileged place that Duchamp’s work occupied in the exceptional art collection that Guggenheim amassed with his. The exhibition thus offers a rare opportunity to examine a significant selection of the artist’s works in relation to one another, an exercise, as Duchamp frequently argued, essential to comprehending his aesthetic project. In so doing, not only can one discern the intricate visual, thematic, and conceptual connections that unify them as an oeuvre, but also one can grasp the extent to which these whimsical, often-hybrid “items” troubled and sometimes totally escaped standard artistic classifications in use at the time of their conception.

Photo: Marcel Duchamp’s dedication to Peggy Guggenheim in her copy of the from or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy (Box in a Valise), 1935–41, cat. no. 6, deluxe edition no. I/XX, January 1941. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

Info: Curator: Paul B. Franklin, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, 701 Dorsoduro, Venice, Italy, Duration: 14/10/2023-18/3/2024, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.guggenheim-venice.it/

![Left: Marcel Duchamp, À propos de jeune sœur (Apropos of Little Sister), October 1911, oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2023Right: Marcel Duchamp, Nu (esquisse) / Jeune homme triste dans un train (Nude [Sketch] / Sad Young Man in a Train), December 1911 (dated 1912), oil on canvas panel, mounted to pressboard, and nailed to stretcher, 100 × 73 cm. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York) © Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2023](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/1_a_propos_de_jeune.jpg)

Right: Marcel Duchamp, Nu (esquisse) / Jeune homme triste dans un train (Nude [Sketch] / Sad Young Man in a Train), December 1911 (dated 1912), oil on canvas panel, mounted to pressboard, and nailed to stretcher, 100 × 73 cm. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York) © Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2023

![Marcel Duchamp, De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy (Boîte-en-valise) (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy [Box in a Valise]), 1935–41, calfskin-covered valise containing paperboard, wood, buckram, oilcloth, velvet, ceramic, glass, cellophane, plaster, iron wire, iron and brass elements; reproductions in collotype, letterpress, and lithography on paper, cellulose acetate, paperboard, and canvas with tempera, watercolor, pochoir, ink, graphite, vegetable resins, and natural gums, 40.9 x 37.7 x 10.4 cm (maximum dimensions, container closed), deluxe edition I of XX. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York) © Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2023](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/3_boite-en-valise.jpg)

Right: Marcel Duchamp with an incomplete example of the Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Valise, 1935–41) at Peggy Guggenheim’s town house, 440 East Fifty-first Street, New York, August 1942. Photograph originally published in Time magazine, September 7, 1942

![Marcel Duchamp, Rotorelief no. 5 – Poisson japonais Part of Rotoreliefs (disques optiques) (Rotoreliefs [Optical Disks]), 1935, six cardboard disks printed recto and verso in color offset lithography, 20 cm (diameter of each), edition of 500 unnumbered sets. Private collection, Paris © Association Marcel Duchamp, by SIAE 2023](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/7_rotorelief_n_5_-_poisson_japonais.jpg)