TRACES: Douglas Gordon

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Douglas Gordon (20/9/1966- ) working across mediums and disciplines, he investigates moral and ethical questions, mental and physical states, as well as collective memory and selfhood. Using literature, folklore, and iconic Hollywood films in addition to his own footage, drawings, and writings, he distorts time and language in order to disorient and challenge. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Douglas Gordon (20/9/1966- ) working across mediums and disciplines, he investigates moral and ethical questions, mental and physical states, as well as collective memory and selfhood. Using literature, folklore, and iconic Hollywood films in addition to his own footage, drawings, and writings, he distorts time and language in order to disorient and challenge. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

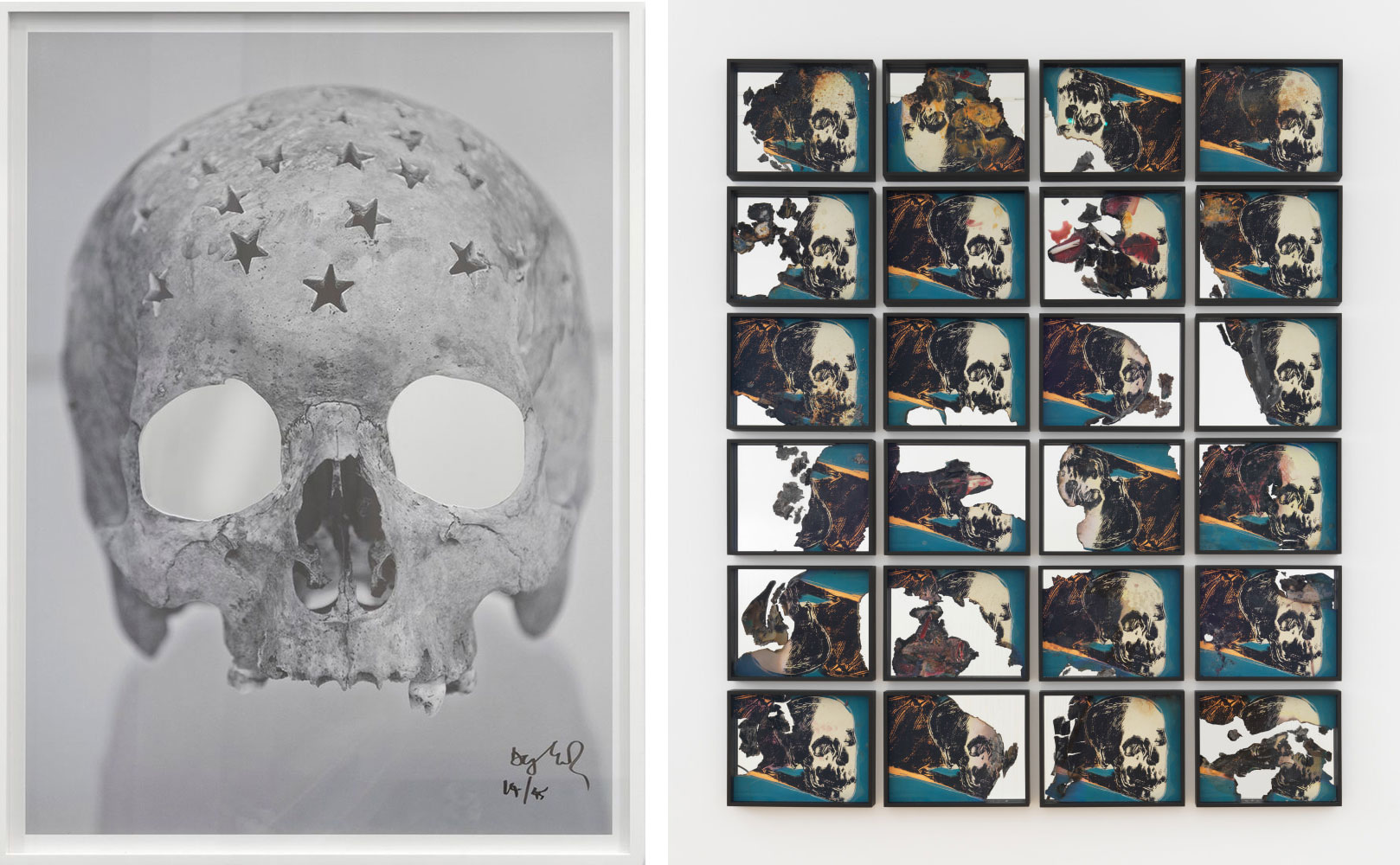

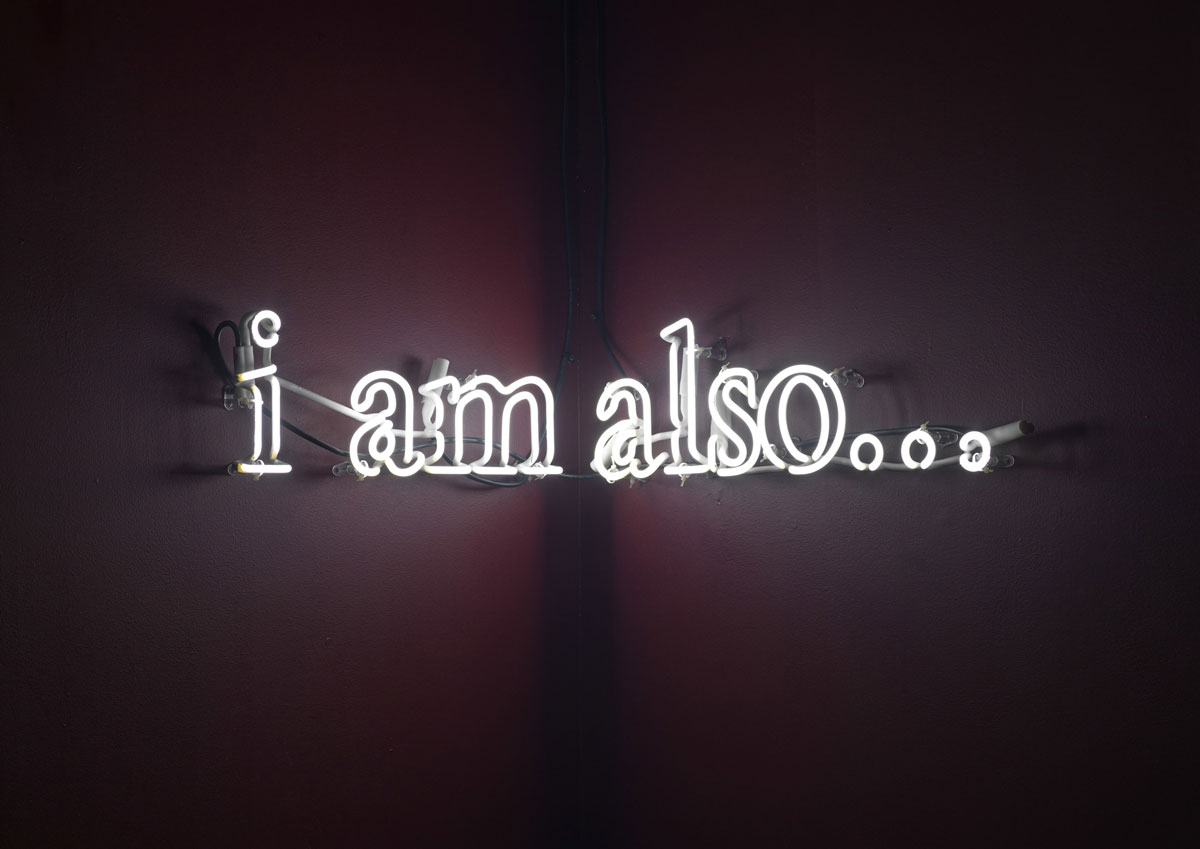

Douglas Gordon was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 20/9/1966 and studied sculpture and environmental art at the Glasgow School of Art (1984–88). After graduating, he attended the Slade School of Fine Art, London (1988–90), where he began to more deeply explore his interests in cinema and film. In 1990 he returned to Glasgow and became involved with Transmission Gallery, an artist-run space that hosted exhibitions and served as a studio and social hub. Two years later Gordon presented “24 Hour Psycho” (1993) at Tramway, Glasgow. The work extends the duration of Alfred Hitchcock’s film “Psycho (1960)” from its original 110 minutes to twenty-four hours; the manipulated footage was played on a large hanging screen in a dark room, which allowed visitors to view the projection from the front or the back. This key work is deceptively simple, but has devastating consequences, exposing the way that memory works in the flow of our consciousness. Everyone knows the plot of Psycho and can anticipate what will happen, but in Gordon’s version, this is constantly frustrated, since the future never seems to come. In the mid-1990s Gordon moved to Cologne, Germany, where he developed “From God to Nothing” (1996), a text piece spanning four walls; Three Inches Black (1997), a series of photographs in which three inches of a finger are tattooed black—the subtext in this case being that three inches is the vital length a blade would need to be in order to inflict a fatal wound; and “Between Darkness and Light (after William Blake)” (1997), a large-scale video installation that pairs a film about divine revelation with another about satanic possession, which was exhibited in an underpass as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster in 1997. Many have attributed Gordon’s ongoing engagement with opposites to his interest in Scottish literary history, in which the tension between good and evil is a predominant theme. In “Tale of a Justified Sinner” (1995) he makes direct reference to Robert Louis Stevenson’s iconic 1886 novel “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” by adapting scenes from a 1932 film version of the story. The scenes are mirrored and slowed down, and switch back and forth between positive and negative in order to emphasize the character’s shifting personalities. In “Déjà-Vu” (2000), composed of footage from Rudolph Maté’s noir “D.O.A.” (1949), the protagonist shifts between life and death through a series of overlapping flashbacks and temporal divergences. In 2000 Gordon had his first survey exhibition in the United Kingdom, “Black Spot”, at Tate Liverpool. The show brought together major works, displayed in a sprawling configuration devised by the artist that spread from the museum’s top floor to the freight elevator to a location outside. In the following years, “Pretty much every film or video work from about 1992 until now,” a nearly comprehensive exhibition of Gordon’s film and video work, was shown in various international locations, including the British School at Rome, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. A retrospective of Gordon’s work opened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2006, presenting thirteen significant films, and “Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from 1989 . . . “, an installation of more than eighty text-based works, opened at Tate Britain, London, in 2010. Two years later Gordon was named a Commandeur dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Republic. Themes of identity, the image of the self, portraits, and mortality continue in Gordon’s more recent sculptures, text works, neons, and film and video works. When the Scottish National Portrait Gallery invited him to create a portrait work for the International Festival in 2017, his response was to make a doppelgänger of their celebrated marble statue of the iconic Scottish poet Robert Burns. “Black Burns” (2017) is an exact replica of the statue in black marble (instead of white Carrara), which Gordon shattered into a few pieces and placed at the foot of the Victorian original. In a related series of sculptures, Gordon depicted parts of his hands and forearms in embracing positions that can be read as either innocent or sinister, expressing the psychological battles at play within an individual. “I had nowhere to go: Portrait of a displaced person” (2016), a filmic portrait of Jonas Mekas, godfather of American avant-garde cinema, premiered at Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel, Germany, in 2017. The following year, Gordon was commissioned to create a work for the new Elizabeth Line station at Tottenham Court Road, London. He compiled a collection of his previous text pieces, some dating back to the late 1980s, when he lived in the area as a student—they are almost memories—and translated them into many languages, reflecting the world community that inhabits London today. This procession of phrases will travel across a huge screen as visitors pass through the ticket hall, on view from early 2023.

Douglas Gordon was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 20/9/1966 and studied sculpture and environmental art at the Glasgow School of Art (1984–88). After graduating, he attended the Slade School of Fine Art, London (1988–90), where he began to more deeply explore his interests in cinema and film. In 1990 he returned to Glasgow and became involved with Transmission Gallery, an artist-run space that hosted exhibitions and served as a studio and social hub. Two years later Gordon presented “24 Hour Psycho” (1993) at Tramway, Glasgow. The work extends the duration of Alfred Hitchcock’s film “Psycho (1960)” from its original 110 minutes to twenty-four hours; the manipulated footage was played on a large hanging screen in a dark room, which allowed visitors to view the projection from the front or the back. This key work is deceptively simple, but has devastating consequences, exposing the way that memory works in the flow of our consciousness. Everyone knows the plot of Psycho and can anticipate what will happen, but in Gordon’s version, this is constantly frustrated, since the future never seems to come. In the mid-1990s Gordon moved to Cologne, Germany, where he developed “From God to Nothing” (1996), a text piece spanning four walls; Three Inches Black (1997), a series of photographs in which three inches of a finger are tattooed black—the subtext in this case being that three inches is the vital length a blade would need to be in order to inflict a fatal wound; and “Between Darkness and Light (after William Blake)” (1997), a large-scale video installation that pairs a film about divine revelation with another about satanic possession, which was exhibited in an underpass as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster in 1997. Many have attributed Gordon’s ongoing engagement with opposites to his interest in Scottish literary history, in which the tension between good and evil is a predominant theme. In “Tale of a Justified Sinner” (1995) he makes direct reference to Robert Louis Stevenson’s iconic 1886 novel “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” by adapting scenes from a 1932 film version of the story. The scenes are mirrored and slowed down, and switch back and forth between positive and negative in order to emphasize the character’s shifting personalities. In “Déjà-Vu” (2000), composed of footage from Rudolph Maté’s noir “D.O.A.” (1949), the protagonist shifts between life and death through a series of overlapping flashbacks and temporal divergences. In 2000 Gordon had his first survey exhibition in the United Kingdom, “Black Spot”, at Tate Liverpool. The show brought together major works, displayed in a sprawling configuration devised by the artist that spread from the museum’s top floor to the freight elevator to a location outside. In the following years, “Pretty much every film or video work from about 1992 until now,” a nearly comprehensive exhibition of Gordon’s film and video work, was shown in various international locations, including the British School at Rome, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. A retrospective of Gordon’s work opened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2006, presenting thirteen significant films, and “Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from 1989 . . . “, an installation of more than eighty text-based works, opened at Tate Britain, London, in 2010. Two years later Gordon was named a Commandeur dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Republic. Themes of identity, the image of the self, portraits, and mortality continue in Gordon’s more recent sculptures, text works, neons, and film and video works. When the Scottish National Portrait Gallery invited him to create a portrait work for the International Festival in 2017, his response was to make a doppelgänger of their celebrated marble statue of the iconic Scottish poet Robert Burns. “Black Burns” (2017) is an exact replica of the statue in black marble (instead of white Carrara), which Gordon shattered into a few pieces and placed at the foot of the Victorian original. In a related series of sculptures, Gordon depicted parts of his hands and forearms in embracing positions that can be read as either innocent or sinister, expressing the psychological battles at play within an individual. “I had nowhere to go: Portrait of a displaced person” (2016), a filmic portrait of Jonas Mekas, godfather of American avant-garde cinema, premiered at Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel, Germany, in 2017. The following year, Gordon was commissioned to create a work for the new Elizabeth Line station at Tottenham Court Road, London. He compiled a collection of his previous text pieces, some dating back to the late 1980s, when he lived in the area as a student—they are almost memories—and translated them into many languages, reflecting the world community that inhabits London today. This procession of phrases will travel across a huge screen as visitors pass through the ticket hall, on view from early 2023.