ART CITIES: Brussels-Francis Alÿs

Throughout his practice, Francis Alÿs consistently directs his distinct poetic and imaginative sensibility toward anthropological and geopolitical concerns centered around observations of, and engagements with, everyday life. His multifaceted projects including public actions, installations, video, paintings, and drawings¬ have involved traveling the longest possible route between locations in Mexico and the United States; pushing a melting block of ice through city streets; commissioning sign painters to copy his paintings; filming his efforts to enter the center of a tornado; carrying a leaking can of paint along the contested Israel/Palestine border; and equipping hundreds of volunteers to move a colossal sand dune ten centimeters.

Throughout his practice, Francis Alÿs consistently directs his distinct poetic and imaginative sensibility toward anthropological and geopolitical concerns centered around observations of, and engagements with, everyday life. His multifaceted projects including public actions, installations, video, paintings, and drawings¬ have involved traveling the longest possible route between locations in Mexico and the United States; pushing a melting block of ice through city streets; commissioning sign painters to copy his paintings; filming his efforts to enter the center of a tornado; carrying a leaking can of paint along the contested Israel/Palestine border; and equipping hundreds of volunteers to move a colossal sand dune ten centimeters.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: WIELS Contemporary Art Centre Archive

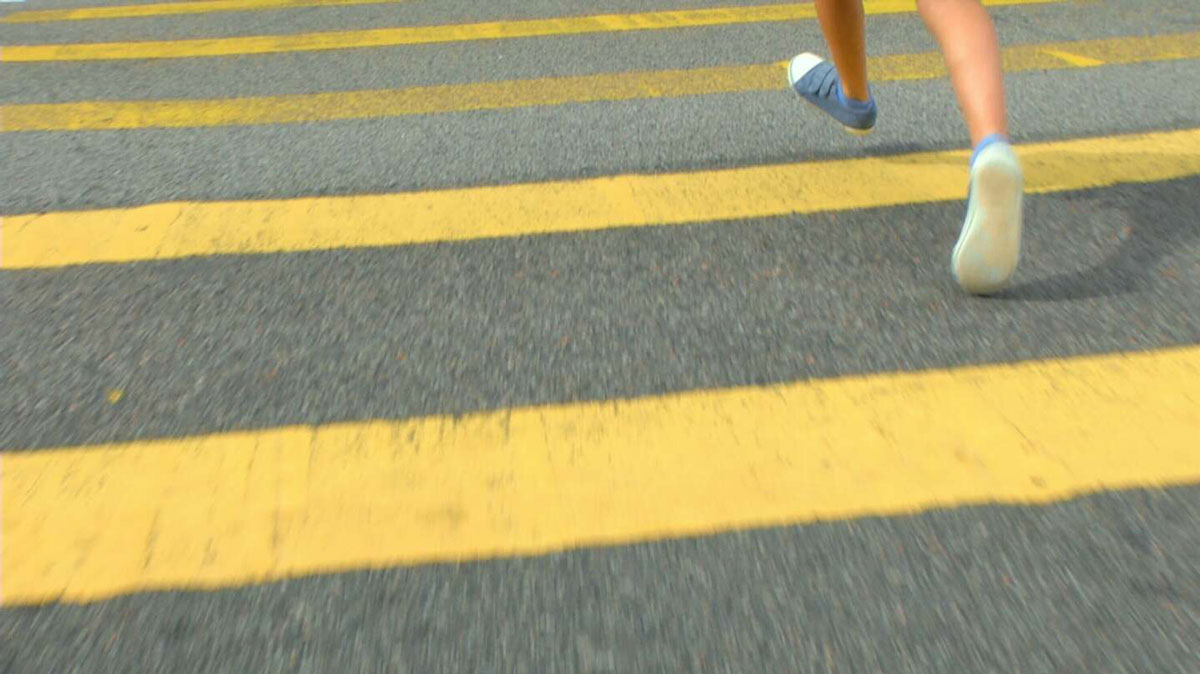

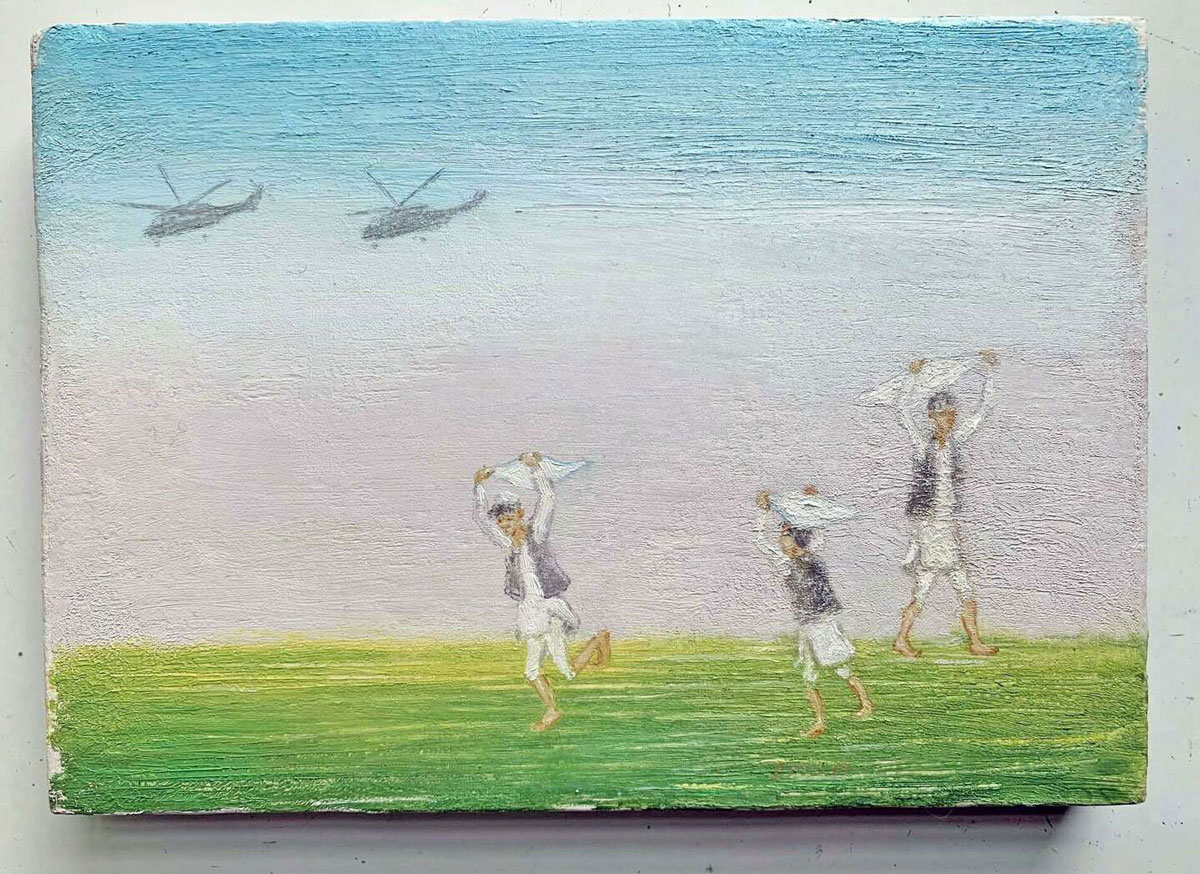

Following his presentation for the Flemish entry for the Belgian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, Francis Alÿs presents this new, more comprehensive version of the exhibition “The Nature of the Game”. Since 1999, during his many travels, Francis Alÿs has documented children playing in public places. At the Venice Biennale, Alÿs presented a series of filmed children games made during the pandemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Belgium, Hong Kong, Mexico and Switzerland, in dialogue with a group of his discreet small-format paintings. For the presentation he completes several new films, including children’s games he recently saw in Ukraine. He confronts them with the film installation “The Silence of Ani” (2015), in which children play hide-and-seek in the ruins of an ancient Armenian city on the edge of present-day Turkey. Using bird calls, the children create the illusion that the city is coming back to life. Play is a basic natural human need, just like eating and sleeping. As children, we learn it instinctively or through imitating others. Children’s play should be seen as a creative relationship between children and the world they live in, as an activity that can sometimes conceal a socio-political dimension. However, as social interactions increasingly take place online in a virtual world, Alÿs captures this moment of profound transition that our society is undergoing and gathers a memory of children’s games before they disappear. While some of the games relate to the traditions of a specific area, others are more universal. Many of these games can also be found in the 16th-century painting “Children’s Games” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a work that made a strong impression on Alÿs when he first saw it as a child. Observing and documenting human behaviour in urban environments is a constant theme in Alÿs’s work. His films record both cultural traditions and children’s spontaneous and unconstrained actions, in the street, as well as in conflict zones and the turbulence of modern life. Children’s games play an important role in investigating the persistence of patterns of popular social behaviour. They have earned a central place in Alÿs’s practice so that he can use his camera to capture the culture and patterns by which people live, sometimes even in places where they seem least likely to occur. “Children’s Games” is an ongoing archive of urban practices that modernization has been banishing from everyday life as the concept of public space is distorted by the domination of motor vehicles and free time by electronic diversions. The children’s games that Alÿs captures constitute a threatened underground culture that brought together generations and crossed borders, and which are extremely interesting due to their conceptual implications. Their rules, images and references project a variety of concepts on time and the world and suggest an ancient, potent substrate underlying our shared experience, which is another reason why we should be concerned with their imminent disappearance. Many of these videos have been shot in relatively economically underdeveloped regions of the world, where the strength of tradition and community have allowed the shared life of a childhood on the street to survive. While they frequently have a direct value as ethnographic documentation, they also metaphorically record transformations and conflicts in contemporary societies. But both in the mysterious way in which certain games are played practically identically in extremely different societies, as well as in their human value, they also become a signifying mechanism that unites a variety of cultures and ways of life.

Photo: Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game 10 / Papalote (video still), Balkh, Afghanistan, 2011, Video, colour, sound, Duration 4’13”, © Francis Alÿs, , Courtesy Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Jan Mot and David Zwirner Gallery

Info: Curators: Dirk Snauwaert & Hilde Teerlinck, WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Avenue Van Volxemlaan 354, Brussels, Belgium, Duration: 7/9/2023-7/1/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.wiels.org/

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #10: Papalote, Balkh, Afghanistan, 2011; 4:13 min, In collaboration with Elena Pardo and Félix Blume, © & Courtesy Francis Alÿs, https://francisalys.com/

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #1: Caracoles, Mexico City, Mexico, 1999; 4:43 min, In collaboration with Julien Devaux, © & Courtesy Francis Alÿs, https://francisalys.com/

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #13: Piñata, Oaxaca, Mexico, 2012; 8:17 min, In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Elena Pardo, and Félix Blume, © & Courtesy Francis Alÿs, https://francisalys.com/

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #29: La roue, Lubumbashi, DR Congo, 2021; 8:43 min, In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, and Félix Blume, © & Courtesy Francis Alÿs, https://francisalys.com/