PRESENTATION: Yan Pei Ming-Painting Histories

Renowned for his deep and passionate reflection on painting in today’s art, Yan Pei-Ming urges us to rethink the relationship between history and the contemporary world, between memory and the present. Exploring such genres as portraiture, landscapes, still lives and historical painting, his pictures take their cue from the model of photographic images from different sources such as the artist’s own personal archive, magazine covers, film stills or celebrated works from art history. Yan Pei-Ming urges us to reflect on the contradiction between reality and depiction, truth and the construction of images – an increasingly topical theme in the digital age where boundaries between private and public, past and present and the reliability of authorship are increasingly blurred.

Renowned for his deep and passionate reflection on painting in today’s art, Yan Pei-Ming urges us to rethink the relationship between history and the contemporary world, between memory and the present. Exploring such genres as portraiture, landscapes, still lives and historical painting, his pictures take their cue from the model of photographic images from different sources such as the artist’s own personal archive, magazine covers, film stills or celebrated works from art history. Yan Pei-Ming urges us to reflect on the contradiction between reality and depiction, truth and the construction of images – an increasingly topical theme in the digital age where boundaries between private and public, past and present and the reliability of authorship are increasingly blurred.

By Efi MIchalarou

Photo: Palazzo Strozzi Archive

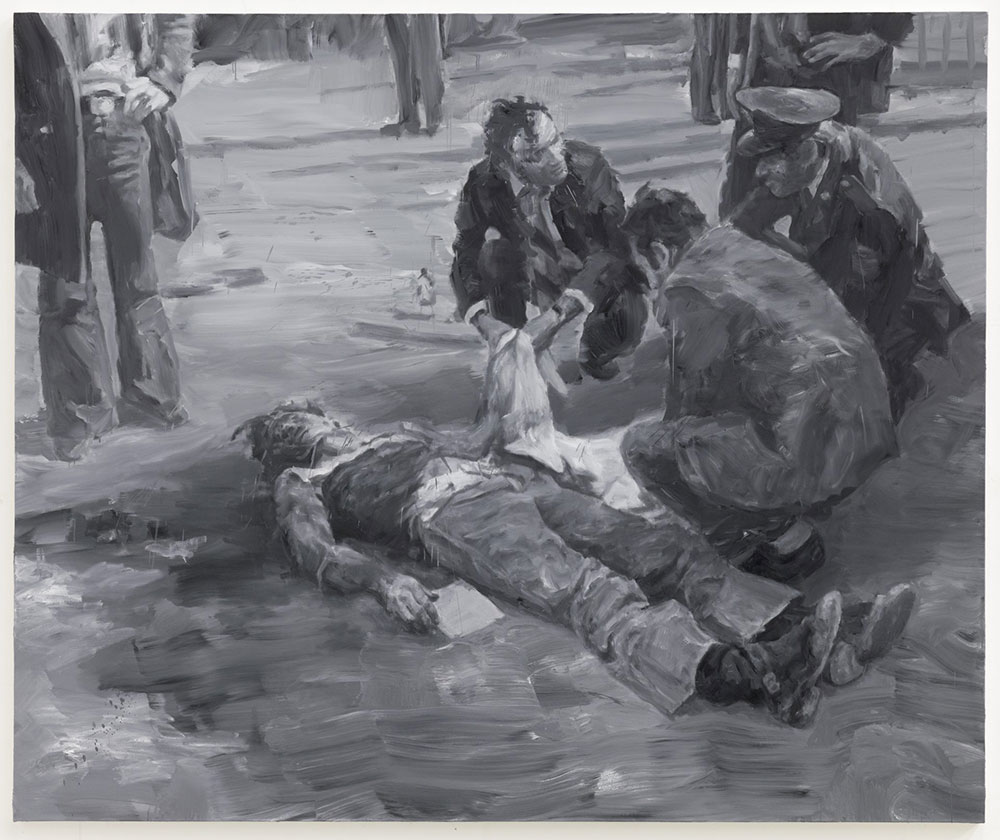

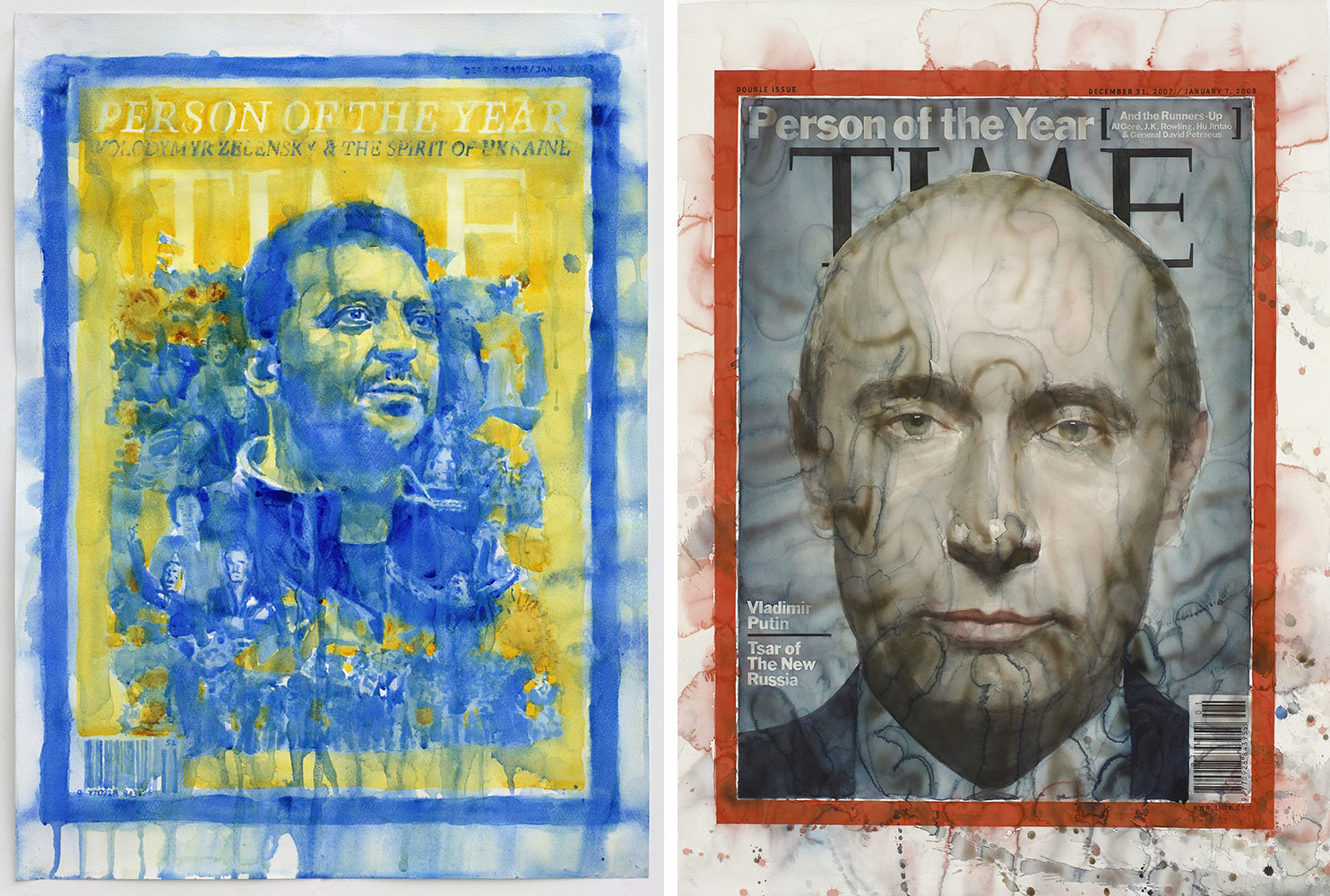

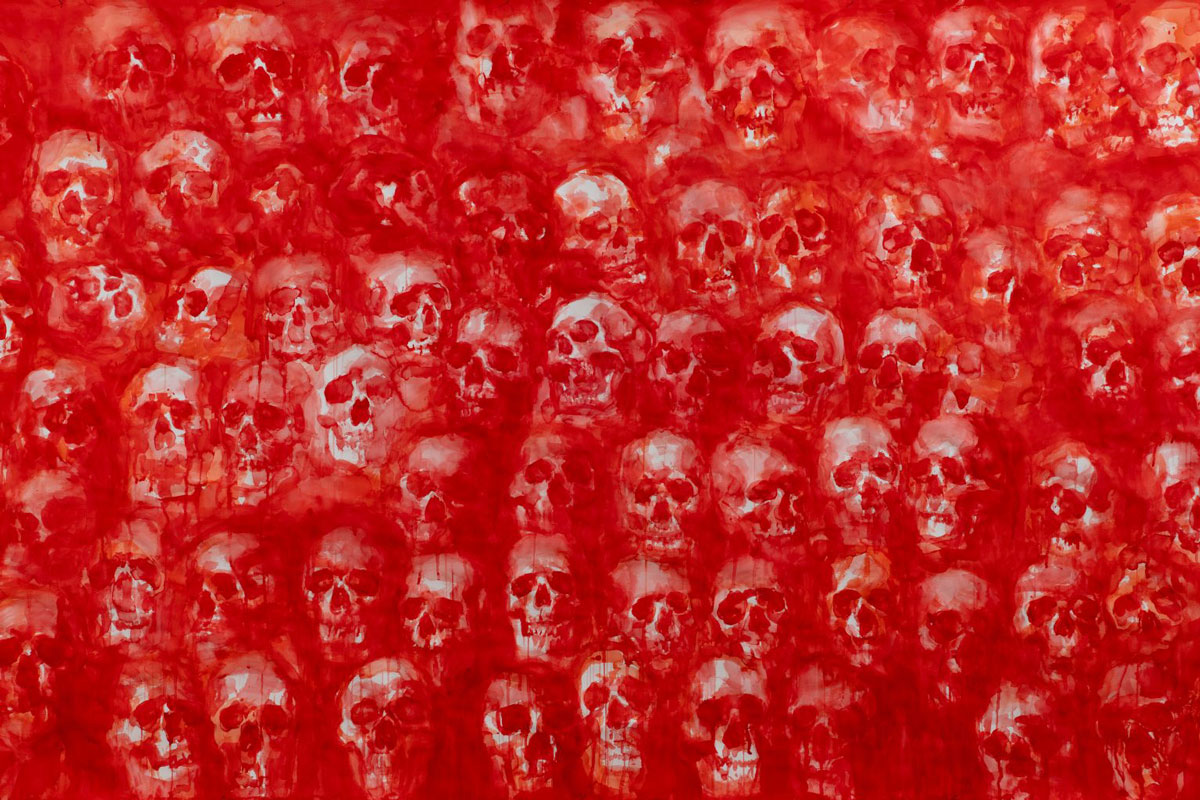

The exhibition “Painting Histories” explore Yan Pei-Ming’s powerful and highly original research into the relationship between image and reality through painted depictions of his personal life alongside important moments, figures and icons from our collective history. It features 30 works, several of which have been created especially for the exhibition, including two TIME magazine covers portraying Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2008 and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in 2023. Making direct links with Italy, the exhibition also showcases a trilogy of new paintings based on famous photographs documenting dramatic moments in Italian’s recent political history: the discovery of Aldo Moro’s body in the boot of a car in Rome in 1978; the body of Pier Paolo Pasolini at the Idroscalo in Ostia in 1975; and the bodies of Benito Mussolini and Claretta Petacci hanging upside-down in Milan’s Piazzale Loreto in 1945. The exhibition alternates these emblematic images with monumental self-portraits and portraits of his mother and father or historical figures such as Mao Zedong and Adolf Hitler, along with original interpretations of such canonical artworks as Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa” or Velazquez’s “Innocent X”. Powerful and intense self-portraits have a unique standing in Yan Pei-Ming’s art; as for all artists, they reveal his thought process and his sensitivity. “Nom d’un chien ! Un jour parfait” (D2012), a title that originates from an exclamation by a critic standing before this canvas, is a frontal, full length self-portrait, in which the subject’s pose evokes the crucifixion, one of the themes drawn from Christian iconography frequently explored by the painter as part of his attempt to establish a cultural syncretism between East and West. In this monumental triptych he therefore chooses to impersonate Christ as well as the two thieves, and he eliminates the crosses while preserving the traditional position of the feet. The figures are floating in an indefinite space, the classic loincloth replaced by anachronistic cutoff jeans. The tightly clenched fists which the central figure brings to its chest evoke the idea of surfacing from a great depth, as if seeking air. There is a cart, too, in this room, to which the artist has applied layers of paint left over from his paintings: it is a digest of more than twenty-five years of work, a tridimensional portrait of sorts, which also concretely represents the passing of time, layer upon layer. Yan Pei-Ming’s portraits are often related to his private life. An example of this are his depictions of his mother, whom he portrayed only once while she was alive. After her death in 2018, he produced a series of monumental works that are a heartfelt tribute to her memory and bear witness to his filial affection. The artist’s focus on the figure of the Buddha is also an act of obeisance towards his mother, a profoundly religious woman, as well as a nostalgic recollection of his childhood: “I’ve been attracted by everything that concerns Buddhism since I was very young,” he explains, “because I was born in a temple and was enveloped in Buddhist culture from the very first moment.” The first Buddha he painted as a child was for his mother; during the Cultural Revolution, worship was banned and these images were forbidden, so the young Yan Pei-Ming painted them for his relatives. As an adult, recalling his mother’s piety, he began to produce figures of the Buddha in series, evoking the rows of sculptures lining Buddhist temples. The delicate scenery instead represents “an ideal landscape, a kind of paradise, where I would like my mother to live.”

When he lived in China, Yan Pei-Ming’s knowledge of western art of the past was mostly limited to the “Mona Lisa and Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel. For this reason, Leonardo’s work acquired great significance in his imagery. Since 2009, when he was invited by the Louvre to measure himself with the masterpiece, the artist has reworked the most famous portrait in the world depicting the subject’s funeral and inserting his own personal experiences into the scene. Not only has he extended the original landscape into two canvases flanking the Mona Lisa, but he has also placed a portrait of his father at the hospital on the left-hand wall and arranged his own imaginary funeral facing it, in which he depicts himself as a young man. With this private interjection into one of the most iconic works in the history of art, Yan Pei-Ming tackles the theme of the father-son relationship, one of the primeval archetypes, by staging a death that goes against the natural principle of life, according to which children should be the ones to bury their fathers, producing a tragedy that is perfectly described in a Chinese saying: “White hair attends black hair’s funeral.” Though Yan Pei-Ming doesn’t recall being close to his father, a silent, reserved man, in his paintings we perceive a very deep, ancestral sentiment that elevates the portrait to a paradigm of Man. “I am interested in the great painters; I keep finding nourishment in their work” Yan Pei-Ming appropriates images produced by artists of the past and reworks them to give them new life, as is the case of “Marat assassiné” (2014), represented by Jacques-Louis David in 1793, where the image is crystallized, its sole purpose that of propaganda. The artist has also produced a blood red “Exécution, après Goya” (2012), from which he has removed the bodies lying on the ground, turning them into flashes that light the nighttime scene, focusing on the execution: all of the depicted figures are still alive, for the artist wishes to display only “those who resist.” Like Bacon, Yan Pei-Ming was profoundly impressed by Velázquez’s “Ritratto di Innocenzo X” from 1650: “I was fascinated… the color is fantastic. It inspired me greatly.” The figure of the pope becomes a symbol of power, its personification, much like his “Napoleon, Crowing Himself Emperor – Purple” (2017), drawn from a preparatory sketch for the large canvas by David at the Louvre (1805–07), in which the Corsican crowns himself before a defeated Pope Pius VII – eliminated by Yan Pei-Ming – to manifest his rejection of papal authority. As Pope Innocent X embodies both political and religious authority, similarly these same prerogatives are combined in Napoleon, whose gesture marks a significant historical moment. The tragedy of WWII, presented in its final moments, is contained in two powerful works by Yan Pei-Ming: in “29 aprile 1945, Piazzale Loreto, Milan” (2022) the body of Mussolini – executed on April 28, 1945 in Como and hung upside down the following day in Milan in Piazzale Loreto, alongside his lover, Claretta Petacci – and the portrait of Adolf Hitler, in “Hitler, d’après Hubert Lanziger” (2012) inspired by Der Bannerträger by the Austrian artist Hubert Lanzinger (1880–1950). The latter painting, produced in 1933, celebrated the rise to power of National Socialism by depicting the Führer on horseback, wearing Medieval armor and holding a standard with a Swastika. At the end of the war, the US Army confiscated the work, and after disparagingly making a hole in the eye of the personification of evil, they shipped it to the United States Army Center of Military History in Washington, D.C., where the historical archives of the United States Army are preserved. Yan Pei-Ming used a photograph and a painting as a source of inspiration for his depiction of this dark, tragic time, evoked by the dog that represents human brutality and by a dark woodland landscape by night, upon which color and scale bestow an allegorical dimension. The smudge of paint on Hitler’s eye further underlines the desire for a damnatio memoriae of an epoch that was terrible in its lack of humanity.

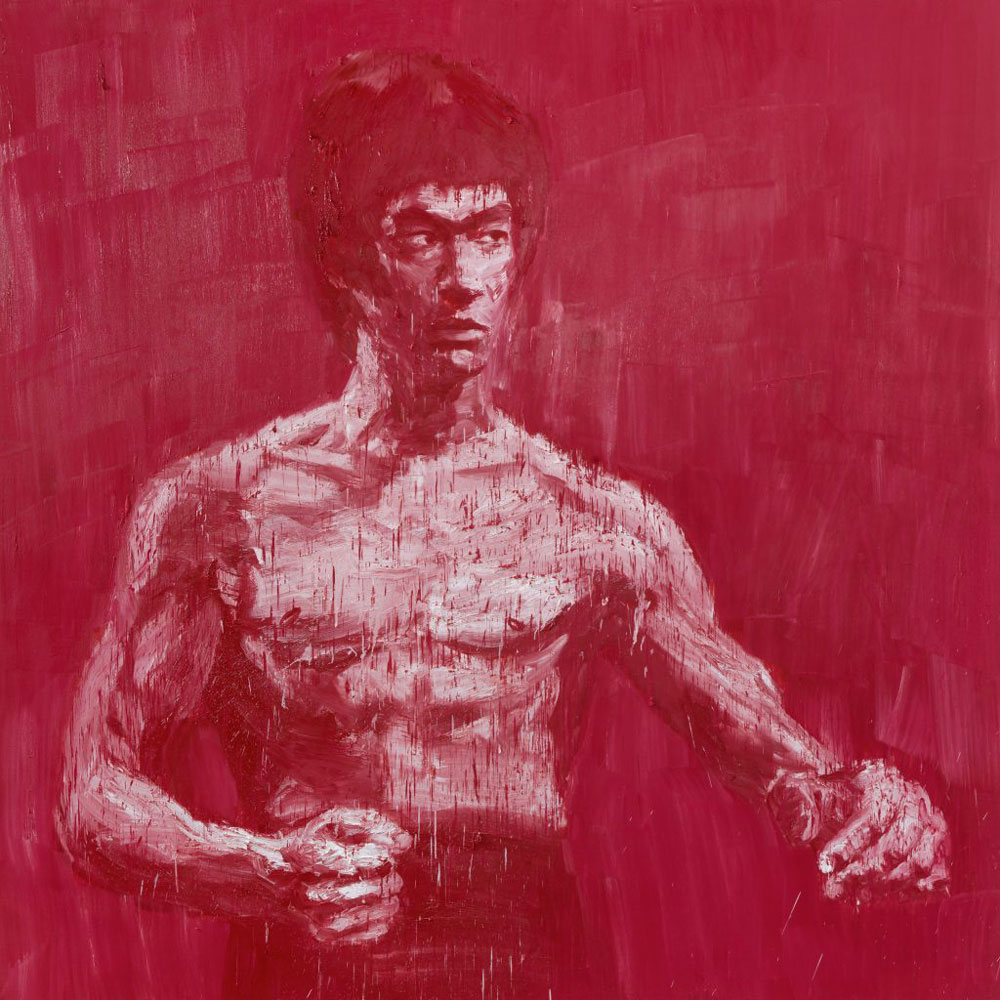

Photo: Yan Pei-Ming, Tigre rouge vermillion de Chine 2023, oil on canvas, 240 × 280 cm Courtesy MASSIMODECARLO and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, Photography: Clérin-Morin, © Yan Pei-Ming, ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Info: Curator: Arturo Galansino, Palazzo Strozzi, Piazza degli Strozzi, Florence, Italy, Duration: 7/7-3/9/23, Days & Hours: Mon-Wed & Fri-Sun 10:00-20:00, Thu 10:00-23:00, www.palazzostrozzi.org/

Right: Yan Pei-Ming, Vladimir Putin, Tsar of The New Russia (detail), 2008, tryptych, watercolour on paper, 210 × 154 cm each, Private collection, Photography: André Morin, © Yan Pei-Ming, ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Right: Yan Pei-Ming, Bouddha pour ma mère 2023, oil on canvas, 300 × 200 cm, Courtesy MASSIMODECARLO and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, Photography: Clérin-Morin © Yan Pei-Ming, ADAGP, Paris, 2023