PRESENTATION: Capturing the Moment

The exhibition “Capturing the Moment” explores the dynamic relationship between contemporary painting and photography. This group exhibition unfolds as an open-ended conversation between some of the greatest painters and photographers of recent generations, looking at how the brush and the lens have been used to capture moments in time, and how these two mediums have inspired and influenced each other.

The exhibition “Capturing the Moment” explores the dynamic relationship between contemporary painting and photography. This group exhibition unfolds as an open-ended conversation between some of the greatest painters and photographers of recent generations, looking at how the brush and the lens have been used to capture moments in time, and how these two mediums have inspired and influenced each other.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Tate Archive

The exhibition “Capturing the Moment” begins with some of the most renowned expressive painters of the post-war period. Visitors can discover how the inventive and painterly realism of artists like Lucian Freud and Alice Neel developed alongside the emergence of documentary photography and ground-breaking photographers like Dorothea Lange. Francis Bacon’s “Study for a Pope VI” (1961) shows the role that photographic source material played for many artists, while Cecily Brown’s “Trouble in Paradise” (1999_ and George Condo’s ‘Mental States” (2000_ reveal the legacy of expressive figurative painting in a world of increasingly prevalent photographic images. The largest section of the exhibition explores how painting and photography have converged, with a selection of major contemporary works which show how both art forms attempt to capture fleeting points in time or moments in history. Gerhard Richter’s photo-realist paintings encapsulate one approach to this, alongside later works by Luc Tuymans and Wilhelm Sasnal. Pop artists like Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Pauline Boty offer another approach, incorporating and collaging photographic images in their paintings. The exhibition is divided in 8 rooms. ROOM 1: Throughout the 20th century, the idea that painting accurately mirrors the world was complicated by artists’ use of photography. Lens-based media could offer a much more convincing representation of reality than painted canvas. Painters developed new styles and perspectives in response to this challenge, particularly when exploring the human figure. Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon use the human form to expose the visceral reality of the self. Whereas Freud preferred to paint from real life, Bacon draws from photographic material. He violently distorts the human figure to reveal what he called ‘the pulsations of a person’. Pablo Picasso had also challenged notions of painterly representation and linear perspective to develop a style known as cubism. In these portraits he collapses multiple perspectives into one single moment in time. Alice Neel and Dorothea Lange aim to depict the social realities of their time through emotionally charged portraits. Neel records everyday life in a working-class New York neighbourhood – painting people as they really are. Lange takes up similar themes through photography, documenting the US Great Depression in emotive portraits of farm labourers in Southern California. ROOM 2: While photographers grapple with the mechanics of the camera, painters continue to work with the surface of the canvas and the texture of paint. They often want to explore the material possibilities of the medium, as well as the painted image itself. The artists in this room harness the expressive power of painterly materials and techniques. They create layered compositions which privilege abstract sensations over depictions of reality. In Francis Bacon’s work every brushstroke is emotionally charged. He approaches the act of painting as an assault upon the human form, creating images of a complex and tormented inner self. Similarly, Paula Rego’s painterly technique forcefully expresses the violence of her subject matter. Breaking down the human figure, Cecily Brown asks questions about how paint can convey the essence of bodies or figures. Can the texture of paint itself transmit the rawness and vibrancy of human flesh? Can painted images, as Bacon, Marwan and George Condo suggest, embody the multiple, fractured facets of the mind? Turning the canvas upside down and upsetting the visual order, Georg Baselitz asks that we look closer, not at the figures but at the painted surface instead. Material, expressive painting such as this resists the precision of the mechanical eye and a world increasingly filled with photographic imagery.

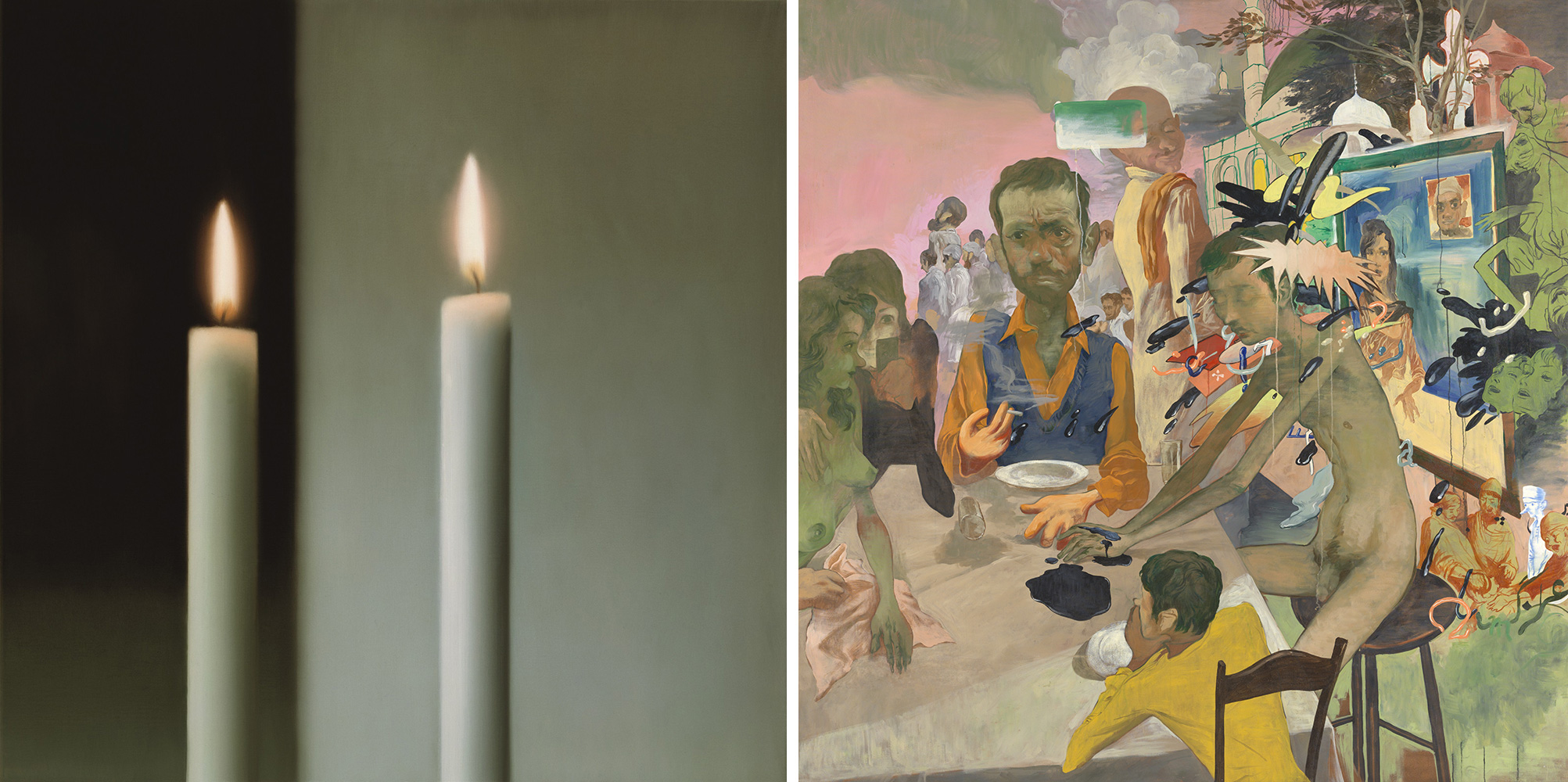

ROOM 3: Jeff Wall’s work explores the boundary between truth and fiction, everyday life and fantasy, challenging the traditional notion that photography faithfully records reality. Wall initially trained as a painter and became interested in cinema, using large-scale photographs mounted on lightboxes as his signature medium. His work depicts landscapes and scenes of contemporary life, inviting viewers to unpick the entwining narratives of fleeting moments. “A Sudden Gust of Wind” captures what seems like an instant frozen in time. It depicts four figures caught in a sudden gust that has swept across the open landscape. The photograph is, however, meticulously staged. The composition is based on a woodcut by Japanese painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), and it took Wall over a year and more than a hundred separate shots to complete. On windy days, Wall photographed actors in a landscape outside Vancouver. He then collaged and digitally superimposed elements of the images together. This analogue process is visible in the nearby “Study for ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai)”. The study also reveals the careful placement of the sheets of paper blowing in the air. They act as a marker of the wind’s direction and draw the visitor’s gaze across the work, animating the scene. There is no sense of connection between the figures; they appear to exist in different moments of time. Wall blurs the boundaries between movement and stillness. He weaves together the traditions of figurative painting with the technology of backlit photography and digital manipulation, to play with the illusion of spontaneity. Wall often declares that he is indebted to historic art, particularly ‘tableau’ paintings, where characters are staged for dramatic effect. ROOM 4: The artists in this room draw on the traditions of painting, using the photographic image to propose new ways of looking. Their spectacular large-scale photographs and precise compositions invite us to delve into the frame and explore collective experience, questioning social structures of representation and truth. Artists such as Pushpamala N., Andreas Gursky and Louise Lawler manipulate their photographs in different ways to explore the constructed nature of image-making. They question what is a truthful representation of reality. Can an image convey the whole picture? Candida Höfer, Louise Lawler and Thomas Struth show us that the way we present and arrange pictures determines what we perceive and how we experience them. How do we behave in a church or in a library, and therefore, how do we experience and understand artworks in these spaces? Does their significance and value change when shown discreetly on the floor, awaiting installation? This room considers the act of looking, at images, at ourselves and at the world. In Struth’s photographs, visitors gaze at paintings that, in turn, look at us. What are they seeing? ROOM 5: Sugimoto’s “Seascapes, capture the infinite, a universal image of the sea that has been encountered throughout generations. The series comprises 220 black-and-white photographs, developed over 30 years in different locations across the world. Somewhere between representation and abstraction, the works depict expansive views of the ocean against cloudless skies. They are punctured by a horizon line that dissects the compositions in half and delineates the limits of visual and mental perception. The “Seascapes, convey the passing of time. Sugimoto refers to these works as ‘time exposed’, alluding to his technique of long exposure, where light gradually burns into the prints to produce an image. Unfolding endlessly beyond the horizon, Sugimoto’s oceans position humanity in stark contrast to the vastness and persistence of nature. They ask us to reflect on the urgent need to protect our rapidly decaying planet, in Sugimoto’s words, to ‘think before destroying ourselves’. ROOM 6: In this room, the artists Gerhard Richter and Wilhelm Sasnal engage with history, media and memory by making paintings which are copies of photographs. In the act of translation from photographic media to painted canvas, harmonies and contradictions emerge between the mediums. We tend to think of photographs as objective images, presenting an unbiased view of history. But does the clarity of the photographic lens obscure and distort as much as it reveals? Richter grew up in post-war East Germany and his photo-paintings are often concerned with histories of conflict, blending personal experience with this wider context. His landscapes are painted from photographs which Richter takes himself. They relate to 19th-century German romantic painters, who saw themselves as mediators between divine nature and painted art. Richter takes the concept of mediation a step further, by painting a moment that has already been captured. This idea of artifice is also present in Two Candles, which adopts the still-life tradition of memento mori – a reminder of death. The fleeting light of the candles is fixed forever as a painted image. The photographs Sasnal paints from are taken from magazines, the Internet, and the ephemera of everyday life. Like Richter, he is interested in how painting can give photographic media a physical presence which somehow transforms the original subject.

ROOM 7: In the 1950s and 60s artists such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Pauline Boty and Richard Hamilton experimented with the medium of painting. They incorporated screenprinting and photographic sources from popular culture, mass media and advertising into their work. This approach of fusing popular imagery and mechanical processes with high art was embraced by artists around the globe, and became known as ‘pop’ art. Artists used screenprinting techniques to appropriate, enlarge and multiply photographic material. A mechanical process that subverted concepts of uniqueness and painterly genius, screenprinting mimicked the influx of images and information in an increasingly mediated world. Pop art works refer to other images – Boty, for instance, painted “Portrait of Derek Marlowe with Unknown Ladies” in response to photographic or cinematic footage of Marlowe and Marilyn Monroe. In works displayed along this wall, Warhol, Boty and Hamilton capture their world and environment, explore the cult of personality and investigate the sexual politics of popular visual culture. Boty exposes the objectification of women; Warhol and Hamilton the constructed and performative nature of masculinity. By multiplying and enlarging the visual noise of modern life, these works expose the complex relationship between image and self. Joan Semmel, John Currin, Paulina Olowska, Lisa Brice and Njideka Akunyili Crosby appropriate photographic images from popular culture in order to reclaim and recentre the female body. In doing so, they complicate the relationship between image-making and self-representation. The camera works in Semmel’s self-portrait as a lens that depicts the reality of her female body, raw, vulnerable, unidealised. Olowska, Currin and Brice push the photographic towards the fantastical, exploring the relationship between images and truthful representations of womanhood. They subvert depictions of the female body as representations of heterosexual male desire. In a world where images and people are in constant flux, Akunyili Crosby explores how images work to construct a sense of self that is hybrid and culturally complex. Together, these works ask us to consider how images can offer distorted or authentic representations of womanhood, and how identity is expressed and mediated through culture. ROOM 8: Artists in this room are grappling with the visual and emotional possibilities of painting in the digital age, and how the medium can respond to our contemporary reality. They assimilate history and its relationship to images to offer new ways of understanding the present. New media, the Internet and archival material collide with the tradition of Western painting to create timely pictorial languages. Lorna Simpson, Salman Toor and Christina Quarles draw from broadcast media to represent political struggles, the ongoing legacy of racism and structural violence in the US, the migrant crisis of the US/Mexico border, and our position in a world that constantly bombards us with news of international conflicts. How does our fraught sociopolitical climate shape individual consciousness? Drawing from lived experience, Toor and Quarles portray the contemporary body as fluid, ambiguous and queer, entangled with others, and inhabiting multiple worlds. Pushing painting towards the edges of representation, Quarles and Owens propose a new mode of mark-making. Whereas gestural painting is traditionally associated with heroic, masculine actions, these artists use digital renderings to create carefully controlled gestures. These marks are no longer tied to the hand of the artist, but are instead connected to the layers of media and images of our information age.

Works by, Michael Armitage, Francis Bacon, Georg Baselitz, Pauline Boty, Lisa Brice, Cecily Brown, Miriam Cahn, George Condo, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, John Currin, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, Jana Euler, Lucian Freud, Andreas Gursky, Richard Hamilton, David Hockney, Candida Höfer, Dorothea Lange, Louise Lawler, Marwan (Marwan Kassab-Bachi), Alice Neel, Paulina Olowska, Laura Owens, Pablo Picasso, Pushpamala N., Christina Quarles, Robert Rauschenberg, Paula Rego, Gerhard Richter, Wilhelm Sasnal, Joan Semmel, Lorna Simpson, Thomas Struth, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Salman Toor, Luc Tuymans, Jeff Wall, Andy Warhol.

Photo: David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972. YAGEO Foundation Collection, Taiwan. © David Hockney. Photo: Art Gallery of New South Wales/Jenni Carter

Info: Tate Modern, Bankside, London, United Kingdom, Duration, 13/6/2023-28/1/2024, Days & Hours, Daily 10,00-18,00, www.tate.org.uk/

Right: Salman Toor, 9PM, the News, 2015. © Salman Toor. Image © Tate (Mark Heathcote and Oliver Cowling)

Right: Pablo Picasso, Buste de Femme, 1938. YAGEO Foundation, Taiwan. © Succession Picasso. DACS, London 2023