PRESENTATION: George Grosz-The Stick Men

George Grosz is one of the principal artists associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, along with Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, and was a member of the Berlin Dada group. After observing the horrors of war as a soldier in World War I, Grosz focused his art on social critique. He became deeply involved in left wing pacifist activity, publishing drawings in many satirical and critical periodicals and participating in protests and social upheavals.

George Grosz is one of the principal artists associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, along with Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, and was a member of the Berlin Dada group. After observing the horrors of war as a soldier in World War I, Grosz focused his art on social critique. He became deeply involved in left wing pacifist activity, publishing drawings in many satirical and critical periodicals and participating in protests and social upheavals.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Das kleine Grosz Museum Archive

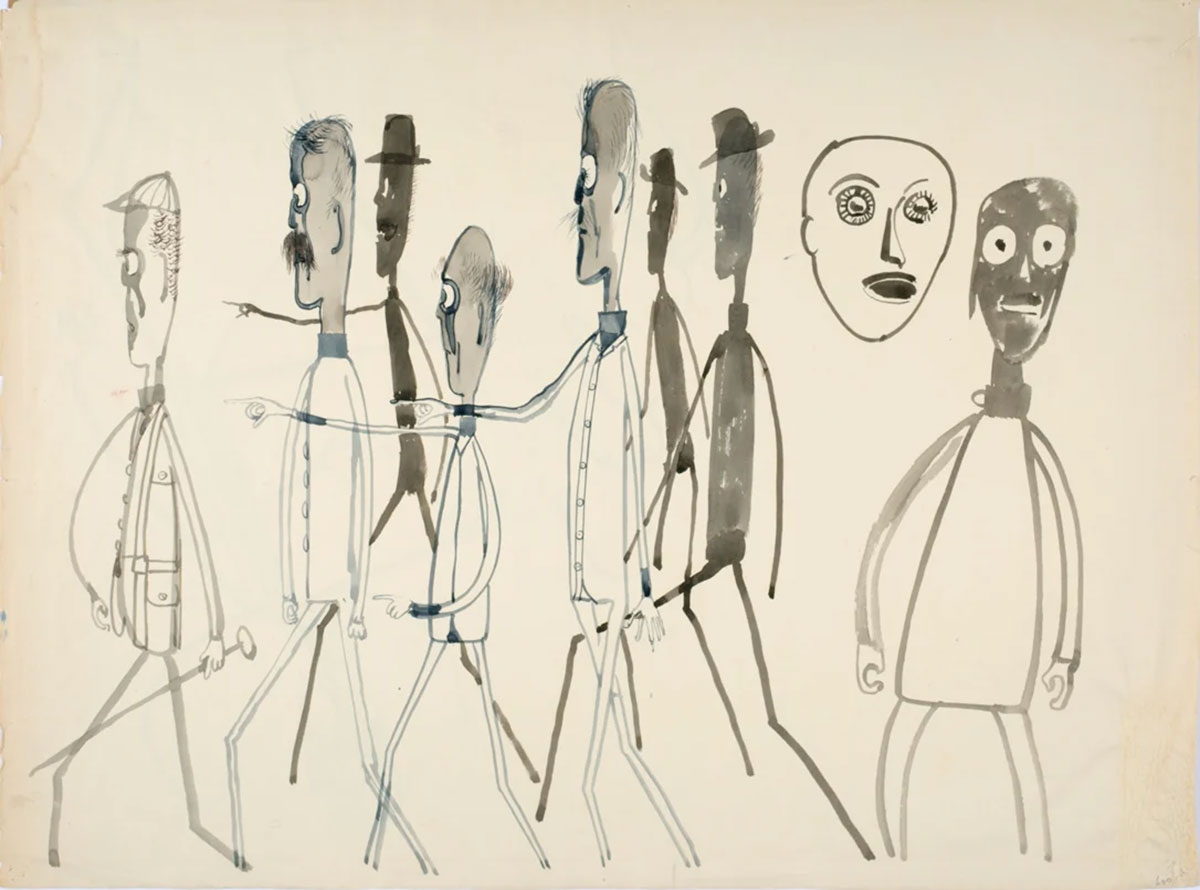

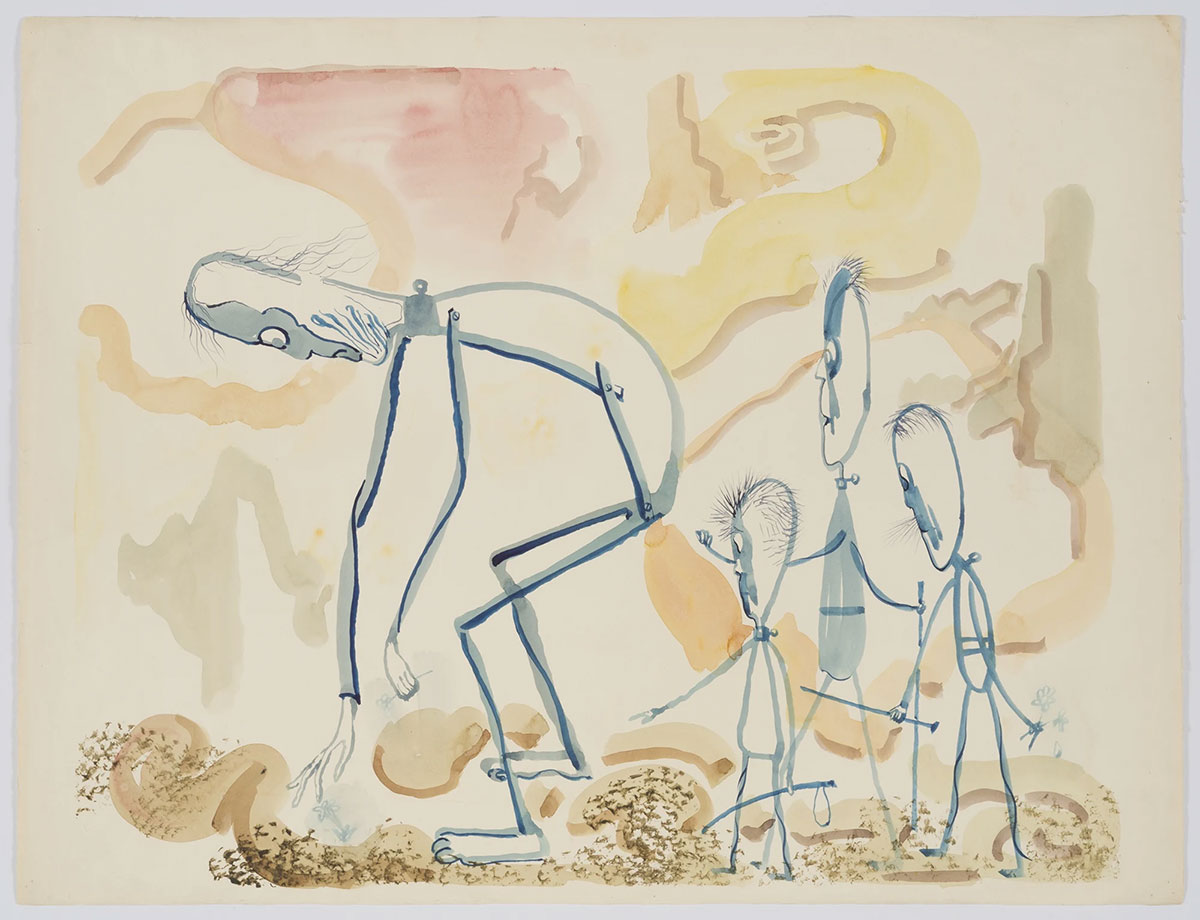

Das kleine Grosz Museum presents the first exhibition dedicated to George Grosz’s last major series of paintings and watercolors series “The Stick Men” George Grosz began the series in the mid-1940s in reaction to the devastating news about the Holocaust and the other atrocities of the Second World War. The deployment of atomic bombs at the end of the war, and the threat of a Third World War, further deepened his pessimistic vision of mankind’s future. He presented his “Stickmen” as dehumanized, famished beings aimlessly wandering through a contaminated, post-apocalyptic world. After studying art in Dresden and Berlin from 1909 to 1912, Grosz sold caricatures to magazines and spent time in Paris during 1913. When World War I broke out, he volunteered for the infantry, but he was invalided in 1915 and moved into a garret studio in Berlin. There he sketched prostitutes, disfigured veterans, and other personifications of the ravages of war. In 1917 he was recalled to the army as a trainer, but shortly thereafter he was placed in a military asylum and was discharged as unfit. By the war’s end in 1918, Grosz had developed an unmistakable graphic style that combined a highly expressive use of line with ferocious social caricature. Out of his wartime experiences and his observations of chaotic postwar Germany grew a series of drawings savagely attacking militarism, war profiteering, the gulf between rich and poor, social decadence, and Nazism. At this time Grosz belonged to the Berlin Dada art movement, having befriended the German Dadaist brothers Wieland Herzfelde and John Heartfield in 1915. Gradually, Grosz became associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) movement, which embraced realism as a tool of satirical social criticism. From his activities, Grosz became a revolutionary figure and had a warrant issued for his arrest by the conservatives during the 1919 Spartakus Revolution. He went into hiding for a time, but continued to draw satirical cartoons for Die Pleite (Bankruptcy) and other satirical magazines like Der Gegner (the Opponent). Grosz’s first solo exhibition took place at Goltz’s Galerie Neue Kunst in 1920. In the same year, he married his longtime girlfriend, Eva Peter. Peter later collaborated with Grosz on erotic, macabre fantasies that often revisited the subject of Lustmord (sexual murder). “Daum” (1920) was exhibited at the First International Dada Fair (1920), along with a portfolio of satirical drawings entitled “Gott mit uns” (1920). The organizers, including Grosz, were put on trial and fined for “grossly insulting the German army. Unfazed, Grosz continued to publish propagandistic materials against the establishment, including “Ecce Homo” (1915-22), another portfolio for which he was accused of pornography and fined.

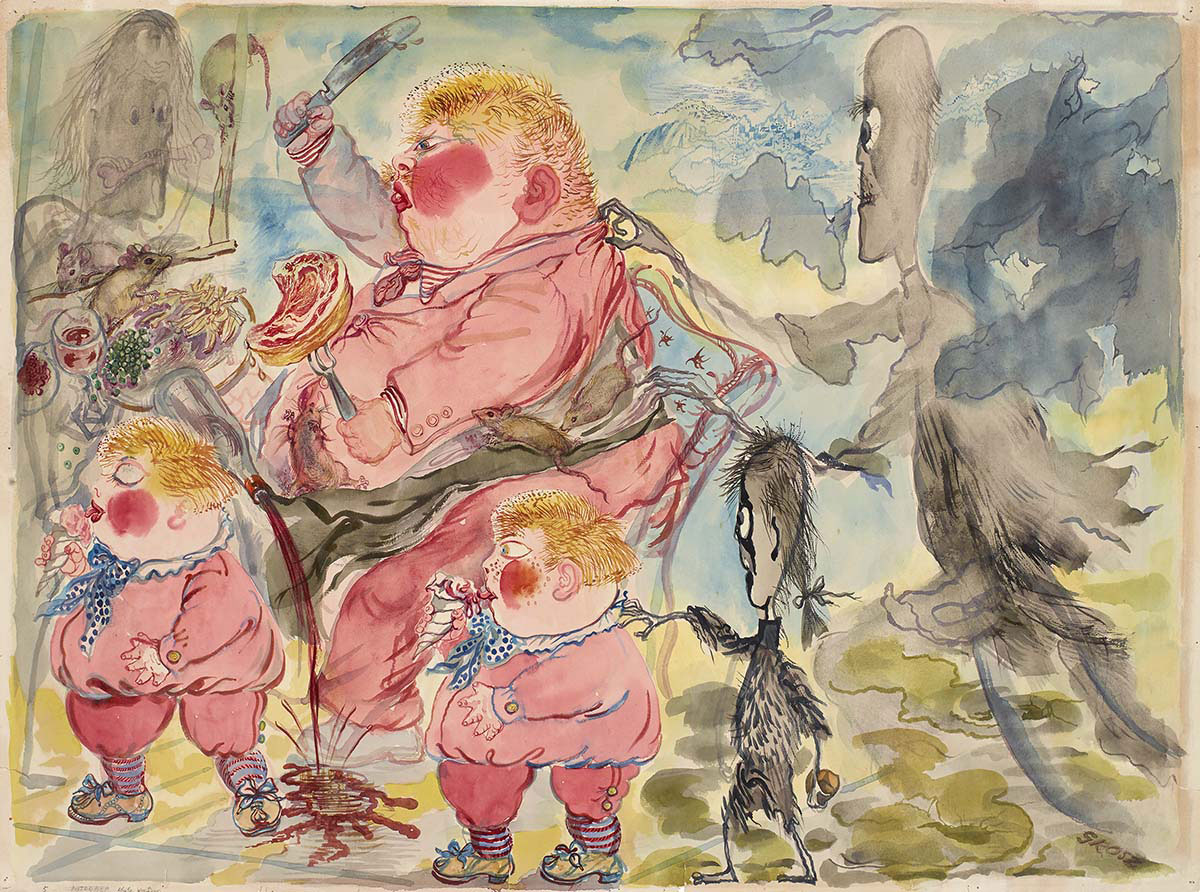

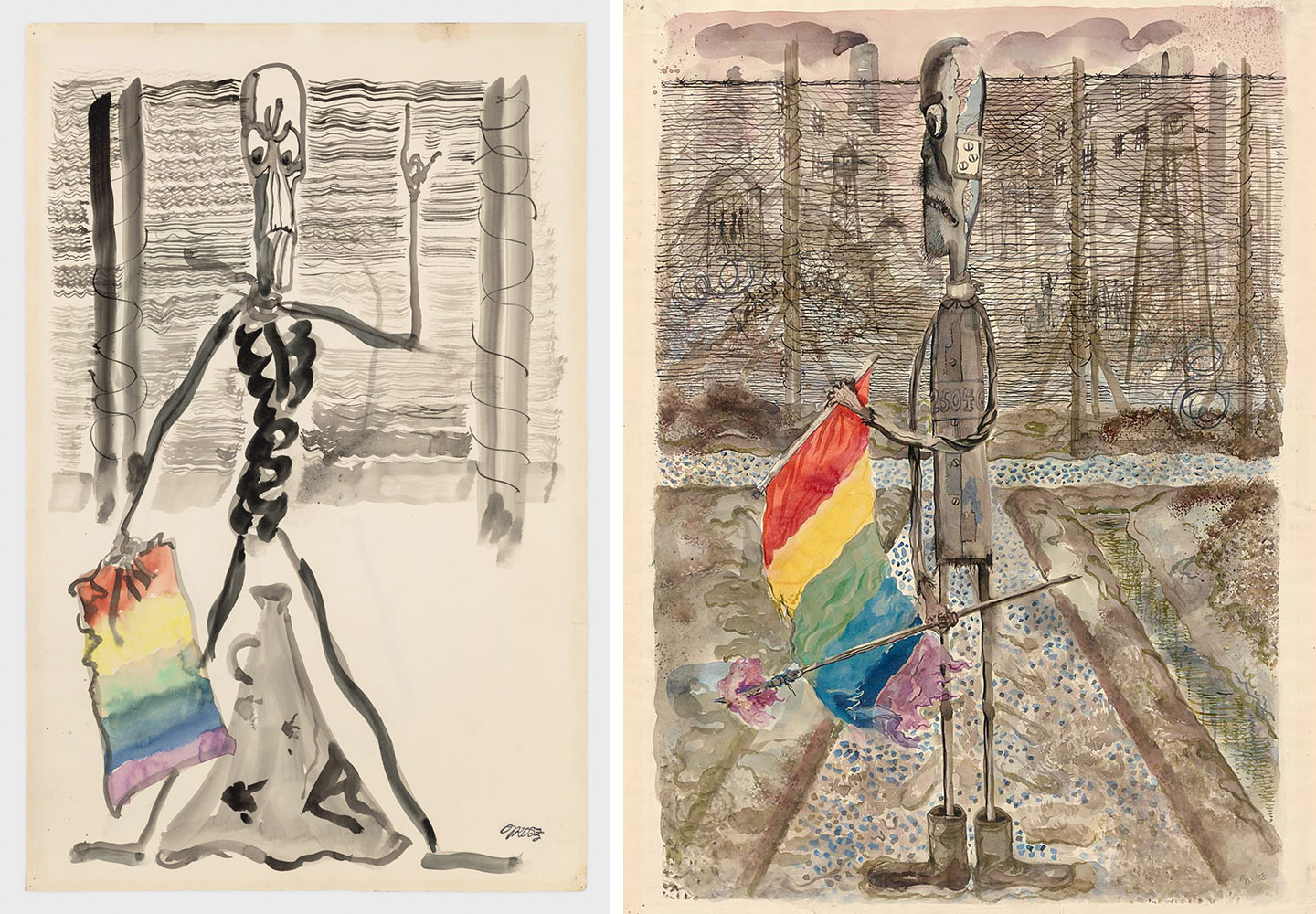

During the 1920s he was recognized internationally as one of Germany’s most important artists who participated in social and political criticism. His renown brought change to his art as well as his life, as he received several portrait commissions, which he completed without any hint of scorn or derision for the sitters. Due to the increasing political instability in Berlin and his antagonistic relationship with the government, Grosz spent several months in Russia and the French Riviera in the mid to late 1920s, before accepting an invitation to teach at the Art Students League of New York in 1932. Returning to Germany for a short time in October 1932, Grosz observed the growing presence of the Nazi party. Shortly before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, he permanently moved his family to the United States. In addition to teaching, Grosz contributed illustrations to magazines such as the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Esquire. In 1933, he opened a private art school with fellow artist Maurice Sterne, but closed the school in 1937 after receiving a two-year grant from the Guggenheim Museum. Having abandoned satirical drawing, Grosz concentrated on painting oil landscapes. Meanwhile, the Nazis’ Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937 in Berlin featured over 200 of his drawings, many of which were confiscated and later destroyed. Grosz gained American citizenship in 1938, and his fame quickly spread after a 1941 retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Despite his status as a hero of the people in Germany and his critical acclaim in America, Grosz made few sales and was forced to resume teaching at the Arts Students League. In 1946, George Grosz moved to Huntington, Long Island, where he would conceive of the “Stickmen”, articulating one of his most harrowing and profound series in the few years that followed. Anatomically, the creatures descended from the insect protagonist of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis”, explaining their spindly bodies and segmented appendages. In the years after the war, Grosz also received letters which described horrific starvation in Germany, where the emaciated walked the streets, driven mad by hunger. The artist’s colorless collective can often be found in pursuit of a fat enemy or trampling on any symbols of color, freedom and individuality, such as the rainbow flag. The plump caricatures who embodied wealth and greed incite the hostile Stickmen, thus leading to their grisly demise. The body of work is imbued with the same pessimism of Giacometti’s sculptures and literary existentialism of the post-war, post-nuclear era.

Photo: George Grosz, Disturbed While Eating, 1947, watercolor and ink on paper, 48 x 64.6 cm, Judin Collection, Courtesy Das kleine Grosz Museum

Info: Das kleine Grosz Museum, Bülowstraße 18, Berlin, Germany, Duration: 25/5-30/10/2023, Days & Hours: Mon & Thu-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.daskleinegroszmuseum.berlin/

Right: George Grosz, The Enemy of the Rainbow, 1946, watercolor and ink on paper, 64.5 × 48 cm, Judin Collection, Courtesy Das kleine Grosz Museum