ARCHITECTURE: Daniel Libeskind

An international figure in architecture and urban design, Daniel Libeskind (12/5/1946- ) is known for introducing complex ideas and emotions into his designs and is renowned for his ability to evoke cultural memory in buildings. Informed by a deep commitment to music, philosophy, literature, and poetry, Mr. Libeskind aims to create architecture that is resonant, unique and sustainable.

An international figure in architecture and urban design, Daniel Libeskind (12/5/1946- ) is known for introducing complex ideas and emotions into his designs and is renowned for his ability to evoke cultural memory in buildings. Informed by a deep commitment to music, philosophy, literature, and poetry, Mr. Libeskind aims to create architecture that is resonant, unique and sustainable.

By Efi MIchalarou

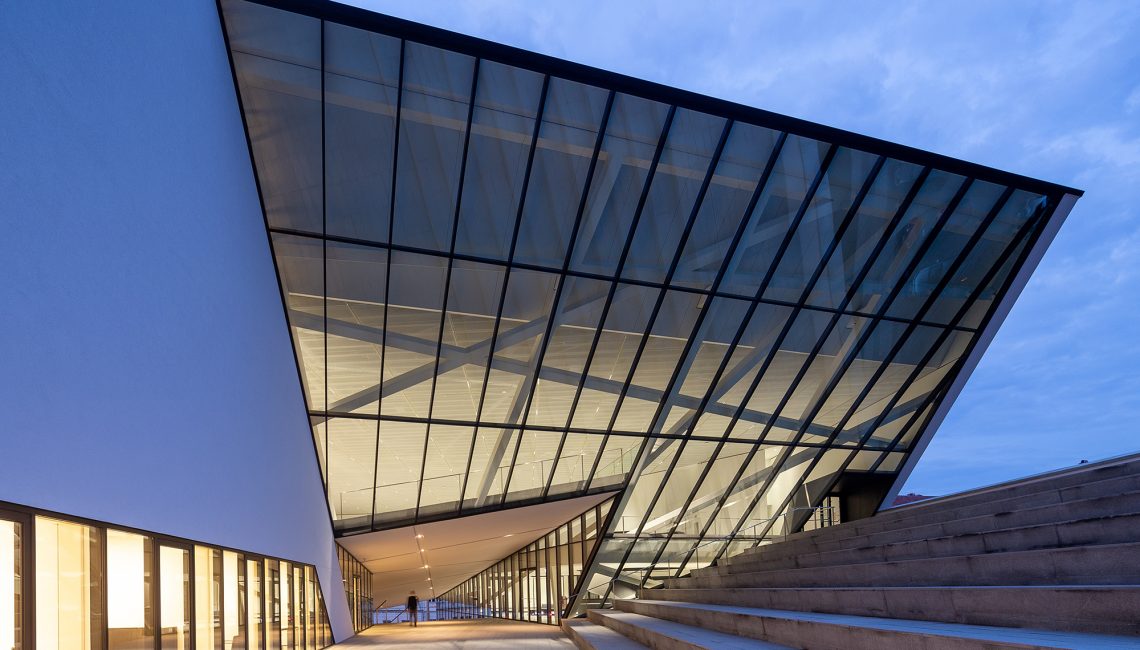

Born in Łódź, Poland, Libeskind was the second child of Dora and Nachman Libeskind, both Polish Jews and Holocaust survivors. As a young child, Libeskind learned to play the accordion and quickly became a virtuoso, performing on Polish television in 1953. He won an America Israel Cultural Foundation scholarship in 1959. In 1957, the Libeskinds moved to Kibbutz Gvat, Israel and then to Tel Aviv before moving to New York in 1959. In his autobiography, “Breaking Ground: An Immigrant’s Journey from Poland to Ground Zero”, Libeskind spoke of how the kibbutz experience influenced his concern for green architecture. In the summer of 1959, his family moved to New York City on one of the last immigrant boats to the United States. Daniel Libeskind was accepted at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and began school there in 1965 where he was taught by John Hejduk and and Peter Eisenman, he received his professional architectural degree in 1970. In 1968, Libeskind briefly worked as an apprentice to architect Richard Meier. He received a postgraduate degree in history and theory of architecture at the School of Comparative Studies at the University of Essex in 1972. The same year, he was hired to work at Peter Eisenman’s New York Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, but he quit almost immediately. Libeskind’s international reputation as an architect was solidified when in 1989 he won the competition to build an addition to the Berlin Museum that would house the city museum’s collection of objects related to Jewish history. Despite a decade of opposition through local politics, the building itself was completed in 1999 and opened as a museum in 2001. Libeskind, who lost most of his family in the Holocaust, worked to convey several levels of meaning in the building. The base of the complex runs in a broken, zigzag pattern, creating a floor plan that resembles the Star of David, which Jews were forced by the Nazis to wear displayed prominently on their clothing. Throughout the length of the museum runs a space known as the Void, which is a path of raw, blank concrete walls. Visitors can see the Void, but they cannot enter it or use it to access other parts of the museum; in this way it suggests both notions of absence and paths not taken. Angular slices of window allow light that creates a disorienting, almost violent feeling throughout the structure, while at the same time an adjacent sculpture garden creates a sense of meditative silence. Because the spatial experience is so powerful, many felt that the building might better serve as a memorial without any installations. Controversy swirled over this proposal until, in 2000–01, Libeskind remodeled the building somewhat to facilitate its museum function. On the basis of the recognition he earned for this project, Libeskind received a number of museum commissions in the late 1990s and early 21st century, including the Imperial War Museum North (1997–2001) in Manchester, England. In 2003 Libeskind won an international competition to rebuild the World Trade Center site in New York City. During the competition phase, much debate arose over whether a new, taller structure should be built or the site left untouched as a form of memorial. Libeskind’s plan thoughtfully addressed both these visions, combining a glass tower, designed to be the tallest in the world, with open memorial gardens that represent the “footprints” of the two fallen towers. His design was praised by both the architectural community and the general public, but commercial and safety concerns ultimately overrode the original design. Still further political and practical considerations influenced the redesign of the tower until all that remained of Libeskind’s vision was the overall height of the building: 540 metres, a reference to the year in which the Declaration of Independence was approved by the U.S. Continental Congress. Libeskind continued to be sought after for Jewish projects. Among these were the interior of the Danish Jewish Museum (completed 2003) in Copenhagen, a glass courtyard (completed 2007) for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum (completed 2008) in San Francisco. He was also tapped for a variety of art museum buildings—including the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal (completed 2007), an extension of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto; and the Frederic C. Hamilton Building (opened 2006), an extension of the Denver Art Museum—and many other structures. Libeskind’s later projects included the Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre (completed 2010), City University of Hong Kong; the extension to the Museum of Military History (2001–11), Dresden, Germany; the Magnet housing development (2008–14), Tirana, Albania; the Ogden Center for Fundamental Physics (completed 2016) at Durham University, England; and MO Museum (completed in 2018), a modern art museum in Vilnius, Lithuania. Throughout his career Libeskind also designed sculptures, furniture, lighting, hardware, and other objects.

Born in Łódź, Poland, Libeskind was the second child of Dora and Nachman Libeskind, both Polish Jews and Holocaust survivors. As a young child, Libeskind learned to play the accordion and quickly became a virtuoso, performing on Polish television in 1953. He won an America Israel Cultural Foundation scholarship in 1959. In 1957, the Libeskinds moved to Kibbutz Gvat, Israel and then to Tel Aviv before moving to New York in 1959. In his autobiography, “Breaking Ground: An Immigrant’s Journey from Poland to Ground Zero”, Libeskind spoke of how the kibbutz experience influenced his concern for green architecture. In the summer of 1959, his family moved to New York City on one of the last immigrant boats to the United States. Daniel Libeskind was accepted at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and began school there in 1965 where he was taught by John Hejduk and and Peter Eisenman, he received his professional architectural degree in 1970. In 1968, Libeskind briefly worked as an apprentice to architect Richard Meier. He received a postgraduate degree in history and theory of architecture at the School of Comparative Studies at the University of Essex in 1972. The same year, he was hired to work at Peter Eisenman’s New York Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, but he quit almost immediately. Libeskind’s international reputation as an architect was solidified when in 1989 he won the competition to build an addition to the Berlin Museum that would house the city museum’s collection of objects related to Jewish history. Despite a decade of opposition through local politics, the building itself was completed in 1999 and opened as a museum in 2001. Libeskind, who lost most of his family in the Holocaust, worked to convey several levels of meaning in the building. The base of the complex runs in a broken, zigzag pattern, creating a floor plan that resembles the Star of David, which Jews were forced by the Nazis to wear displayed prominently on their clothing. Throughout the length of the museum runs a space known as the Void, which is a path of raw, blank concrete walls. Visitors can see the Void, but they cannot enter it or use it to access other parts of the museum; in this way it suggests both notions of absence and paths not taken. Angular slices of window allow light that creates a disorienting, almost violent feeling throughout the structure, while at the same time an adjacent sculpture garden creates a sense of meditative silence. Because the spatial experience is so powerful, many felt that the building might better serve as a memorial without any installations. Controversy swirled over this proposal until, in 2000–01, Libeskind remodeled the building somewhat to facilitate its museum function. On the basis of the recognition he earned for this project, Libeskind received a number of museum commissions in the late 1990s and early 21st century, including the Imperial War Museum North (1997–2001) in Manchester, England. In 2003 Libeskind won an international competition to rebuild the World Trade Center site in New York City. During the competition phase, much debate arose over whether a new, taller structure should be built or the site left untouched as a form of memorial. Libeskind’s plan thoughtfully addressed both these visions, combining a glass tower, designed to be the tallest in the world, with open memorial gardens that represent the “footprints” of the two fallen towers. His design was praised by both the architectural community and the general public, but commercial and safety concerns ultimately overrode the original design. Still further political and practical considerations influenced the redesign of the tower until all that remained of Libeskind’s vision was the overall height of the building: 540 metres, a reference to the year in which the Declaration of Independence was approved by the U.S. Continental Congress. Libeskind continued to be sought after for Jewish projects. Among these were the interior of the Danish Jewish Museum (completed 2003) in Copenhagen, a glass courtyard (completed 2007) for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and the Contemporary Jewish Museum (completed 2008) in San Francisco. He was also tapped for a variety of art museum buildings—including the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal (completed 2007), an extension of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto; and the Frederic C. Hamilton Building (opened 2006), an extension of the Denver Art Museum—and many other structures. Libeskind’s later projects included the Run Run Shaw Creative Media Centre (completed 2010), City University of Hong Kong; the extension to the Museum of Military History (2001–11), Dresden, Germany; the Magnet housing development (2008–14), Tirana, Albania; the Ogden Center for Fundamental Physics (completed 2016) at Durham University, England; and MO Museum (completed in 2018), a modern art museum in Vilnius, Lithuania. Throughout his career Libeskind also designed sculptures, furniture, lighting, hardware, and other objects.