PORTFOLIO: Sally Mann

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Sally Mann (1/5/1951- ). For more than 40 years, she has been taking hauntingly beautiful, experimental photographs that explore the essential themes of existence: memory, desire, mortality, family and nature’s overwhelming indifference towards mankind. What gives unity to this vast corpus of portraits, still lifes, landscapes and miscellaneous studies is that it is the product of one place, the southern United States. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Sally Mann (1/5/1951- ). For more than 40 years, she has been taking hauntingly beautiful, experimental photographs that explore the essential themes of existence: memory, desire, mortality, family and nature’s overwhelming indifference towards mankind. What gives unity to this vast corpus of portraits, still lifes, landscapes and miscellaneous studies is that it is the product of one place, the southern United States. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

Sally Turner Munger (Sally Mann) was the youngest of three children born to Robert Munger, a doctor who drove around Lexington, Virginia. Sally’s primary maternal figure, however, was her nanny, an African-American woman named Virginia Carter who took day-to-day care of Sally and her siblings. She described her childhood, during which she usually played unclothed, as “‘unconventional’, ‘rural’ and ‘near-feral'”, adding that, we were “middle class but bohemian: no church, no country club, no television”. Having inherited his love of photography, Sally would borrow her father’s 5×7 camera (which may account for her preference for large format photography in her professional career). He also bought his daughter her first Leica (35mm hand-held) camera. In 1969, Sally graduated from the Putney School, a private boarding school in Vermont. While at Putney, she signed up to a photography module (though she later admitted that her primary motivation was to be able to be alone with her boyfriend in the darkroom). One of her first photographic works was a nude portrait of a classmate. She then attended Bennington College, , where she studied with South African photographer and filmmaker, Norman Sieff. Having met him a year earlier at Bennington, Sally took the initiative and proposed to Larry Mann, a blacksmith/trainee attorney, who was three years her senior. Sally and Larry Mann were married in 1970. Mann studied briefly at Friends World College, a small independent liberal arts institution that later merged with Long Island University (later Friends World Program). She then enrolled at Hollins College (now Hollins University) in Roanoke, Virginia, from where she graduated with first class honors, in 1974. The following year she earned an MA in creative writing, also from Hollins. Soon after graduating a second time, Mann worked as an architectural photographer for Washington and Lee University, documenting the construction of the school’s new law school building, the Lewis Hall. This led to Mann’s first solo exhibition in 1977 at Washington, D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the publication of her, “Lewis Law Portfolio” (1977). In 1979 Mann gave birth to the first of her three children. As art critic Richard B. Woodward explains, “Her solution to the demands of motherhood, which have eaten away at the schedules of artistic women throughout the ages, was ingenious: with her children as subjects, making art became a kind of childcare”. Emmett (who later served in the peace keeping corps of the military) was followed, respectively, in 1981 and 1985, by two daughters, Jessie and Virginia. Emmett suffered three significant brain injuries (the first when he was hit by a car as in childhood, and the two others resulting from accidents in adulthood) and was later diagnosed as schizophrenic. Said Mann, “We don’t know if the injuries caused it, or exacerbated it, or if it was genetic”.

Sally Turner Munger (Sally Mann) was the youngest of three children born to Robert Munger, a doctor who drove around Lexington, Virginia. Sally’s primary maternal figure, however, was her nanny, an African-American woman named Virginia Carter who took day-to-day care of Sally and her siblings. She described her childhood, during which she usually played unclothed, as “‘unconventional’, ‘rural’ and ‘near-feral'”, adding that, we were “middle class but bohemian: no church, no country club, no television”. Having inherited his love of photography, Sally would borrow her father’s 5×7 camera (which may account for her preference for large format photography in her professional career). He also bought his daughter her first Leica (35mm hand-held) camera. In 1969, Sally graduated from the Putney School, a private boarding school in Vermont. While at Putney, she signed up to a photography module (though she later admitted that her primary motivation was to be able to be alone with her boyfriend in the darkroom). One of her first photographic works was a nude portrait of a classmate. She then attended Bennington College, , where she studied with South African photographer and filmmaker, Norman Sieff. Having met him a year earlier at Bennington, Sally took the initiative and proposed to Larry Mann, a blacksmith/trainee attorney, who was three years her senior. Sally and Larry Mann were married in 1970. Mann studied briefly at Friends World College, a small independent liberal arts institution that later merged with Long Island University (later Friends World Program). She then enrolled at Hollins College (now Hollins University) in Roanoke, Virginia, from where she graduated with first class honors, in 1974. The following year she earned an MA in creative writing, also from Hollins. Soon after graduating a second time, Mann worked as an architectural photographer for Washington and Lee University, documenting the construction of the school’s new law school building, the Lewis Hall. This led to Mann’s first solo exhibition in 1977 at Washington, D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the publication of her, “Lewis Law Portfolio” (1977). In 1979 Mann gave birth to the first of her three children. As art critic Richard B. Woodward explains, “Her solution to the demands of motherhood, which have eaten away at the schedules of artistic women throughout the ages, was ingenious: with her children as subjects, making art became a kind of childcare”. Emmett (who later served in the peace keeping corps of the military) was followed, respectively, in 1981 and 1985, by two daughters, Jessie and Virginia. Emmett suffered three significant brain injuries (the first when he was hit by a car as in childhood, and the two others resulting from accidents in adulthood) and was later diagnosed as schizophrenic. Said Mann, “We don’t know if the injuries caused it, or exacerbated it, or if it was genetic”.

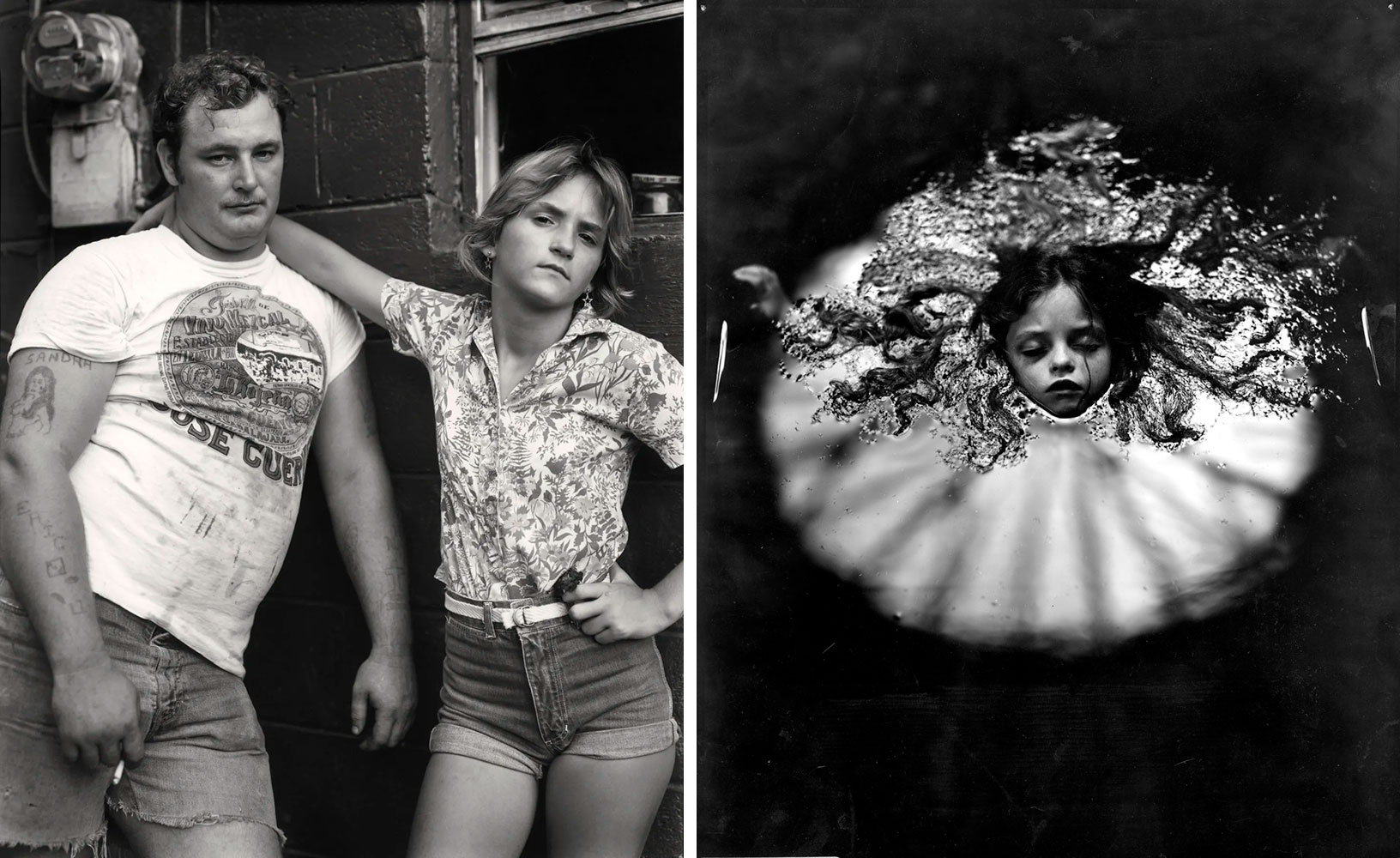

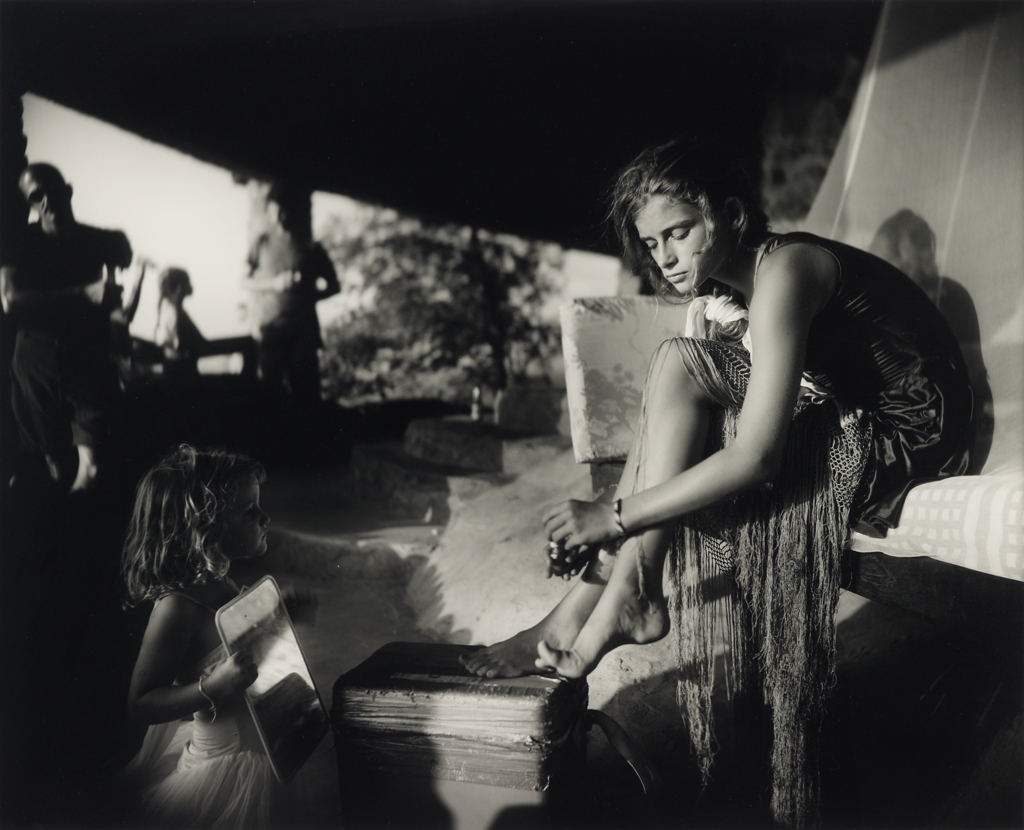

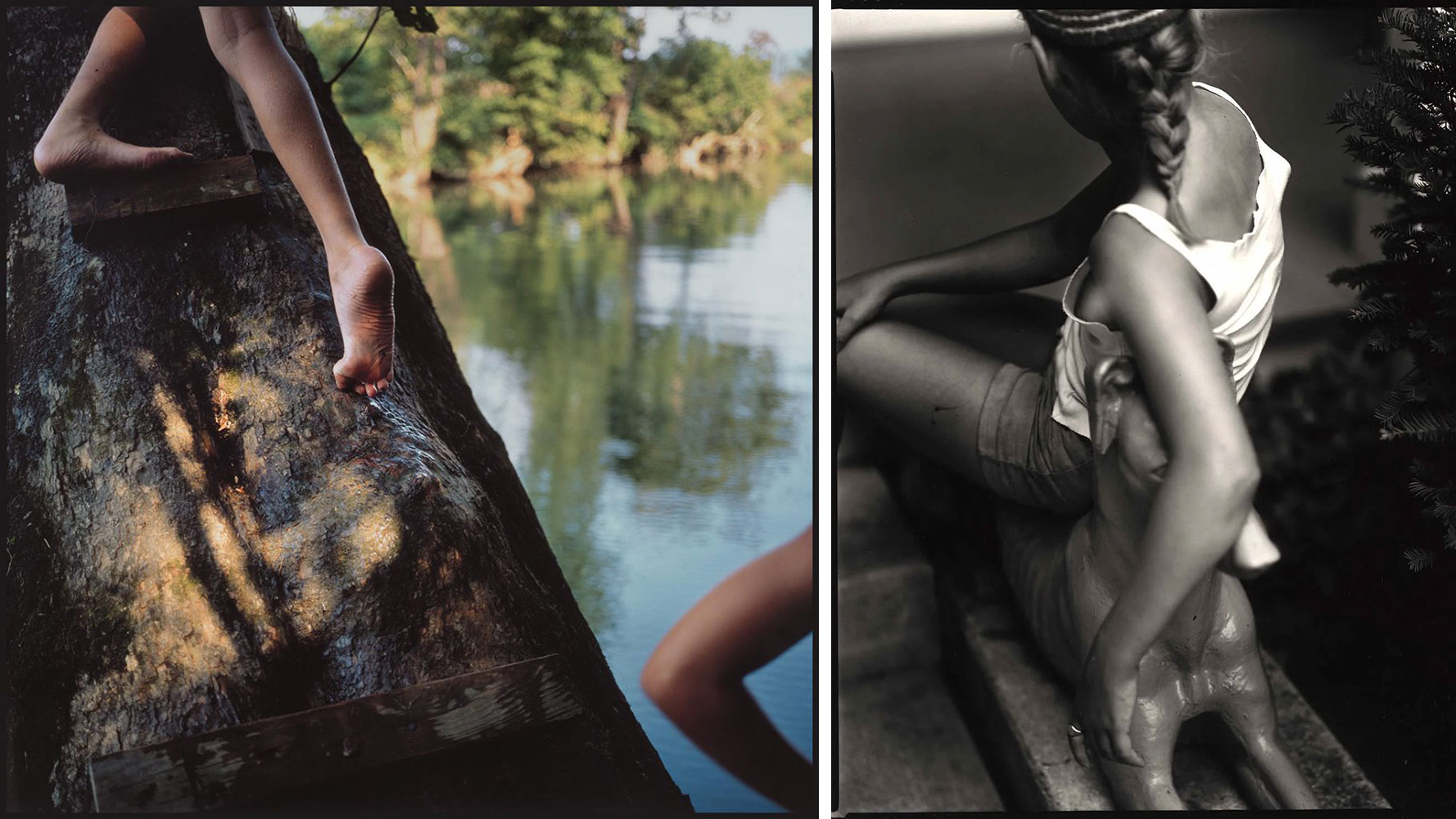

Mann’s first anthology, “Second Sight”, was published in 1984. But it would be four more years before Mann gained acclaim and notoriety in equal measure with the publication of “At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women” (1988). The collection featured portraits of twelve-year-old girls, taken with Mann’s antique 8×10 view camera. It was an early example of Mann’s preference for older photographic technologies and processes which lend her images a vintage, almost otherworldly, quality. As if anticipating the criticism that accompanied Mann’s portraits, the book featured an introduction by the novelist Ann Beattie who wrote, “These girls still exist in an innocent world in which a pose is only a pose–what adults make of that pose may be the issue”. Mann’s case was not helped when it emerged that one of the images in the series, “Untitled (Theresa and the Tattooed Man)”, seemed to confirm the worries of her critics. The image shows a young girl in tight denim shorts with her arm resting on the shoulders of a large, tattooed adult. There is a palpable sense of friction between the two subjects (Mann later said how the girl refused to move any closer to the man). Indeed, a few months after the photograph was taken, it was claimed that the man, Theresa’s mother’s boyfriend, had been sexually abusing the girl and was duly shot in the face with a pocket pistol by the girl’s mother. Theresa’s mother stated in court that while she was working evening shifts at a local truck stop, her boyfriend was “at home partying and harassing my daughter”. In 1991, during an exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum, broadcast evangelist Rev. Vic Eliason contacted the police and the district attorney claiming that Mann was exploiting her own children by exhibiting “indecent” images of them. No legal action was taken against Mann, but Eliason’s protest signaled the start of an on-going controversy in which Mann would have to defend her art against accusations of immorality and/or child pornography. The family portraits gained further notoriety when journalist Raymond Sokolov published an article in the Wall Street Journal, entitled Critique: Censoring Virginia, which was accompanied by a reproduction of a photograph of Mann’s naked four-year-old daughter Virginia, but with black bars placed across her eyes, nipples, and pubic region. Commenting on the censored image, Mann said, “it felt like a mutilation, not only of the image but also of Virginia herself and of her innocence. It made her feel, for the first time, that there was something wrong not just with the pictures but with her body”. The controversy surrounding Mann’s family portraits, which was published to acclaim as the collection, “Immediate Family”, in 1992, was addressed in a 1994 film, “Blood Ties: The Life and Work of Sally Mann”. The film was nominated for an Academy Award, Best Documentary, Short Subjects. Sadly, in 1996 Larry was diagnosed with the muscle wasting disease, muscular dystrophy. Mann would chronicle in pictures the impact of the disease on her husband’s body over the coming decade.

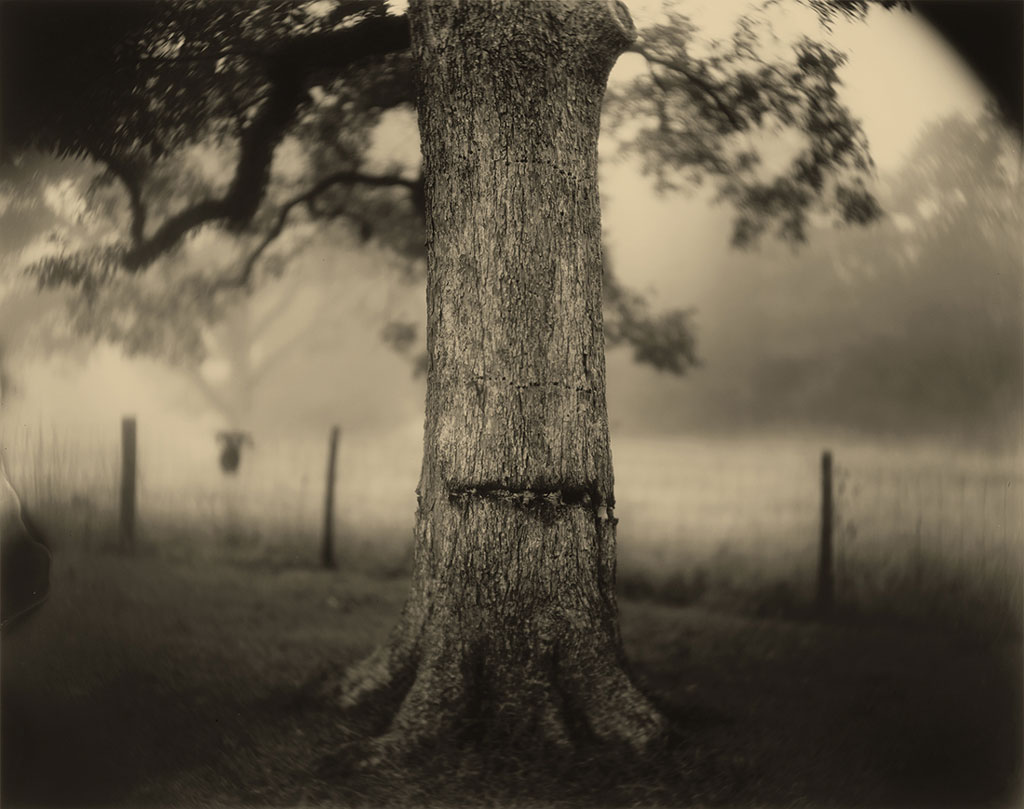

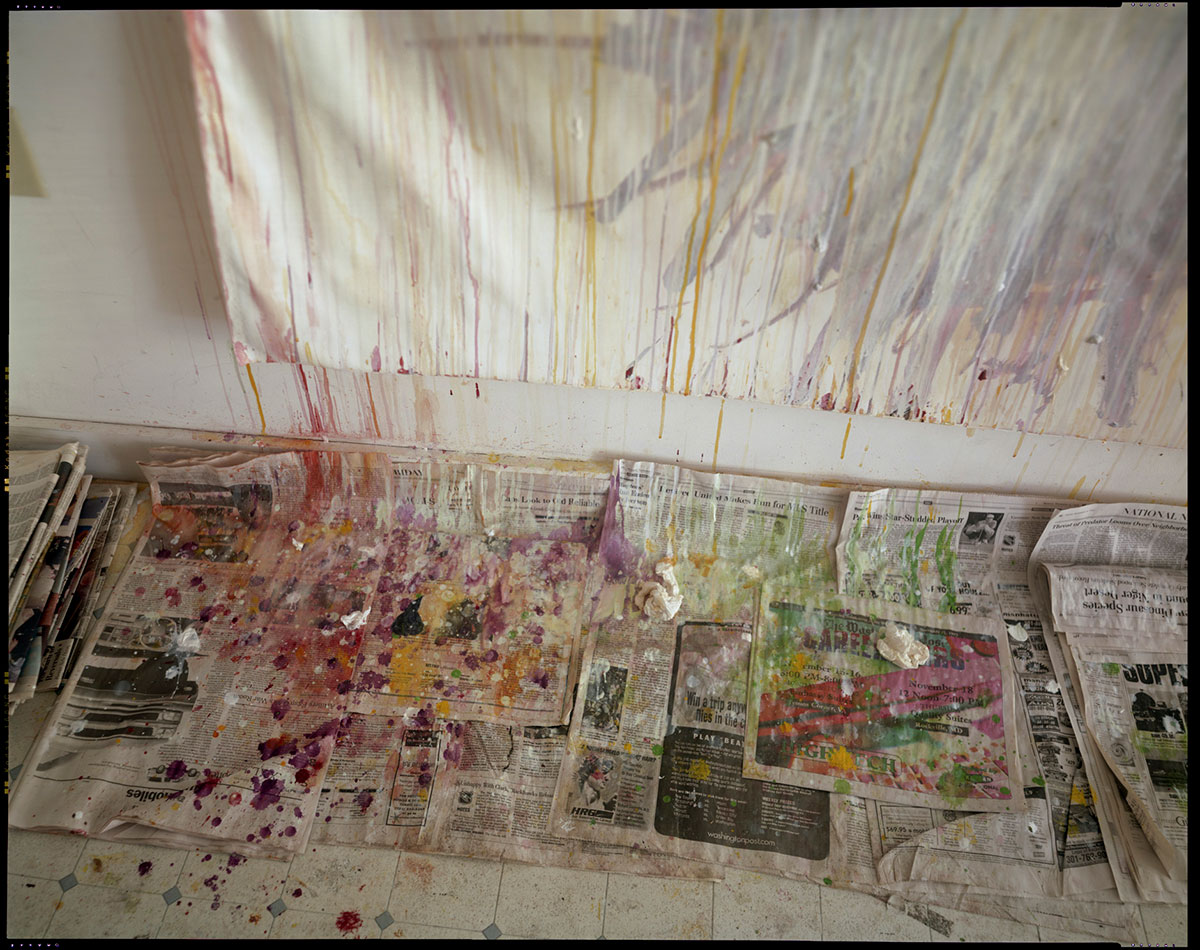

Mann was close friends with abstract artist Cy Twombly, who also lived in Lexington. They were first introduced by Mann’s father, who, in the mid-1940s, invited Twombly (then a high school senior) over to dinner. Mann’s parents were also early patrons of Twombly’s work, purchasing one of his house-paint and pencil paintings in 1955. Between 1999 and Twombly’s passing in 2011, Mann photographed the artist and his studio. Mann and Twombly also spent time together outside the studio, sitting on his favorite bench at the local Walmart or visiting a local Antique Mall where he enjoyed perusing kitschy objects. Several of her portraits of Twombly were collected in the book “Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington” (2016)). In the early 2000s, Mann turned her attentions to the theme of death. For her 2001 “Body Farm” series, Mann had joined students at the University of Tennessee Forensic Anthropology Facility which housed a large fenced-off wooded area where recently deceased human remains – hence “Body Farm” – were placed in scenarios meant to replicate real homicide scenes. Many of Mann’s “Body Farm” images appeared in her 2003 book, “What Remains”, which includes other images focused on the theme of death, including photographs taken in-and-around her own Lexington farmstead (such as the decomposing body of her pert greyhound, Eva). From the late 1990s, Mann had been experimenting with the glass negative and wet plate collodion process that was pioneered as far back as the 1850s. The technique involves coating a glass plate with a syrupy substance (collodion) and washing it in a light-sensitive solution of silver salts. Mann employed this process, which gives the image a mysterious, vintage quality, in her series of the landscapes of the American South, “Last Measures” (2003) and “Deep South” (2005). Of the “Deep South” series, Mann had returned to the sites of civil war battles and photographed the landscapes as they exist now. Mann had also started exploring alternative ways of working with the collodion process. She experimented with ambrotypes and tintypes which are underexposed collodion plates that produce as positive images set against a black background. The former is formed when the glass plate is tinted and coated with lacquer on one side; the latter exemplified in such works as “Untitled (Self-Portrait)” (2012) is rendered on a thin sheet of black-lacquered metal rather than glass. In 2009 Mann published her book, “Proud Flesh.” It was the outcome of a six-year project in which Mann had documented, using the collodion process, her husband’s journey with his muscle wasting disease. In 2011, Mann presented a lecture series titled “If Memory Serves” for the William E. Massey, Sr. Lecture in the History of American Civilization, and worked on her memoir, “Hold Still”, which was published in 2015. But tragedy struck the Mann family again in the same year when (her son) Emmett took his own life. Mann spent several months at home in a state of shock. Since then, Mann has made great strides in processing her grief, and returned to work, most recently exploring issues related to race relations and the history of slavery in the American South. She and Larry still live in Lexington (in the home they built together on her family’s farm).