PHOTO:Tina Modotti

Tina Modotti (Assunta Adelaide Luigia Modotti, 16/8/1896-6/1/42) was a photographer, actress and political activist. Her career as a photographer only spanned about 9 years, but yielded some very important works. Her interest in photography started early on and it was through her association with Edward Weston (as his model and partner). Along with her close friends Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Modotti created photographs that mixed the romanticism of Mexican culture with the radically charged political climate of latin America in the early 20th Century.

Tina Modotti (Assunta Adelaide Luigia Modotti, 16/8/1896-6/1/42) was a photographer, actress and political activist. Her career as a photographer only spanned about 9 years, but yielded some very important works. Her interest in photography started early on and it was through her association with Edward Weston (as his model and partner). Along with her close friends Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Modotti created photographs that mixed the romanticism of Mexican culture with the radically charged political climate of latin America in the early 20th Century.

By Dimitris Lempesis

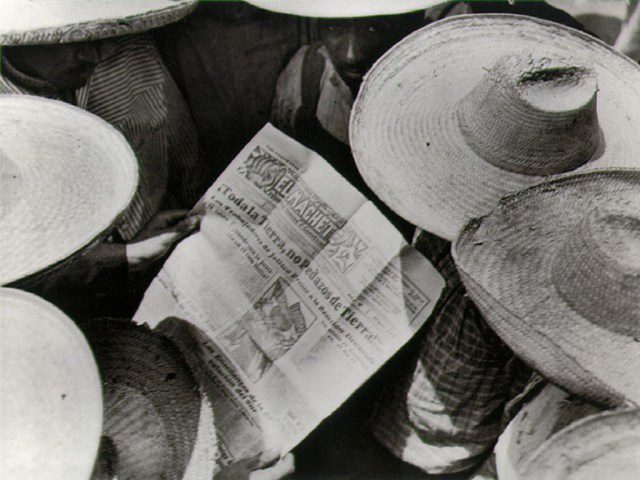

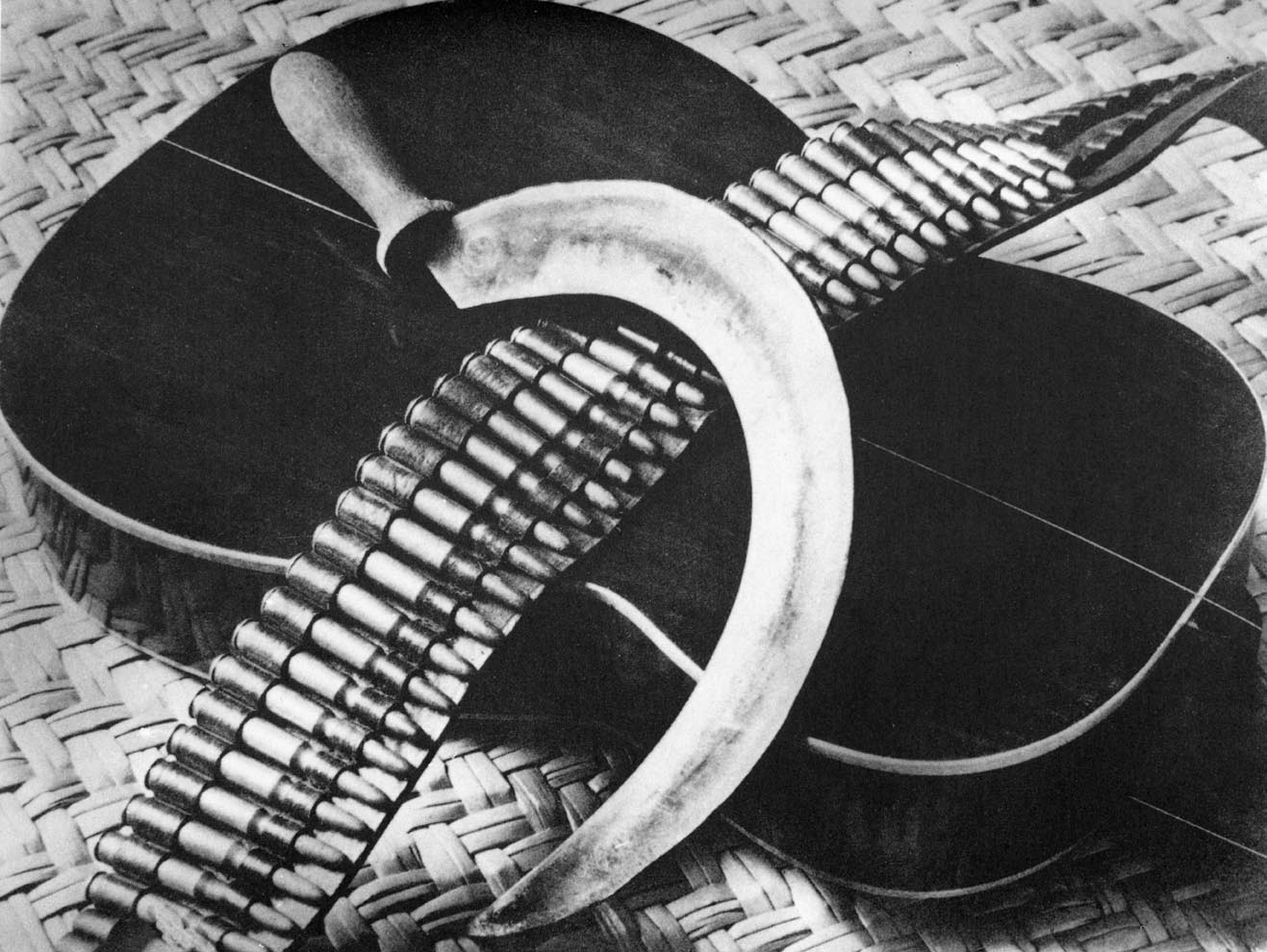

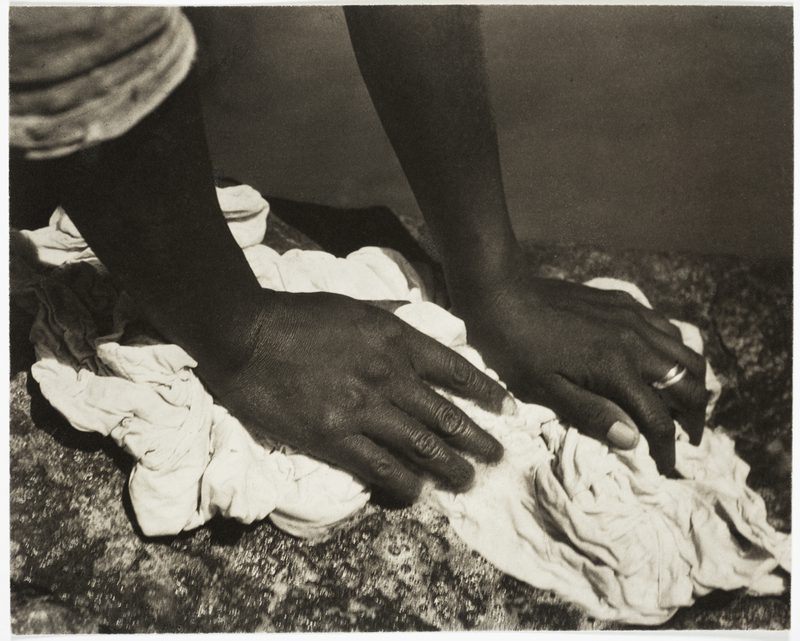

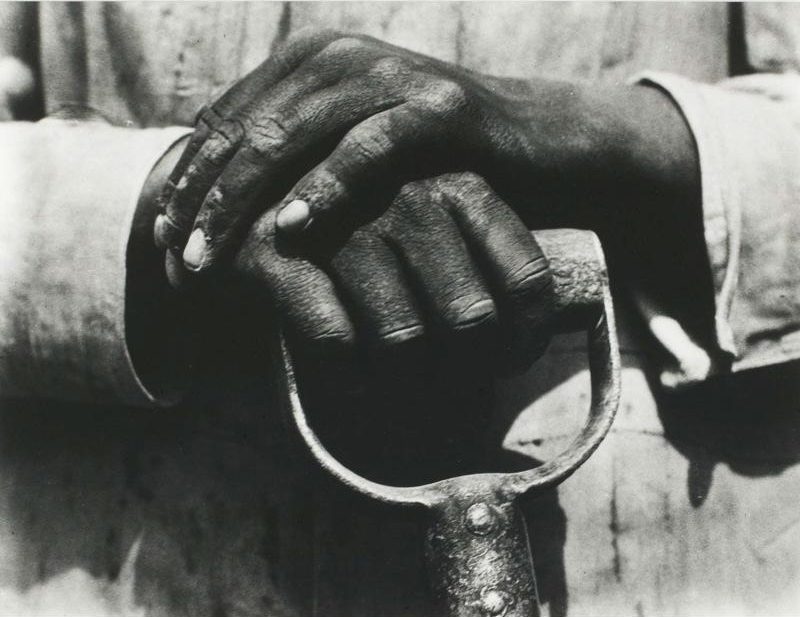

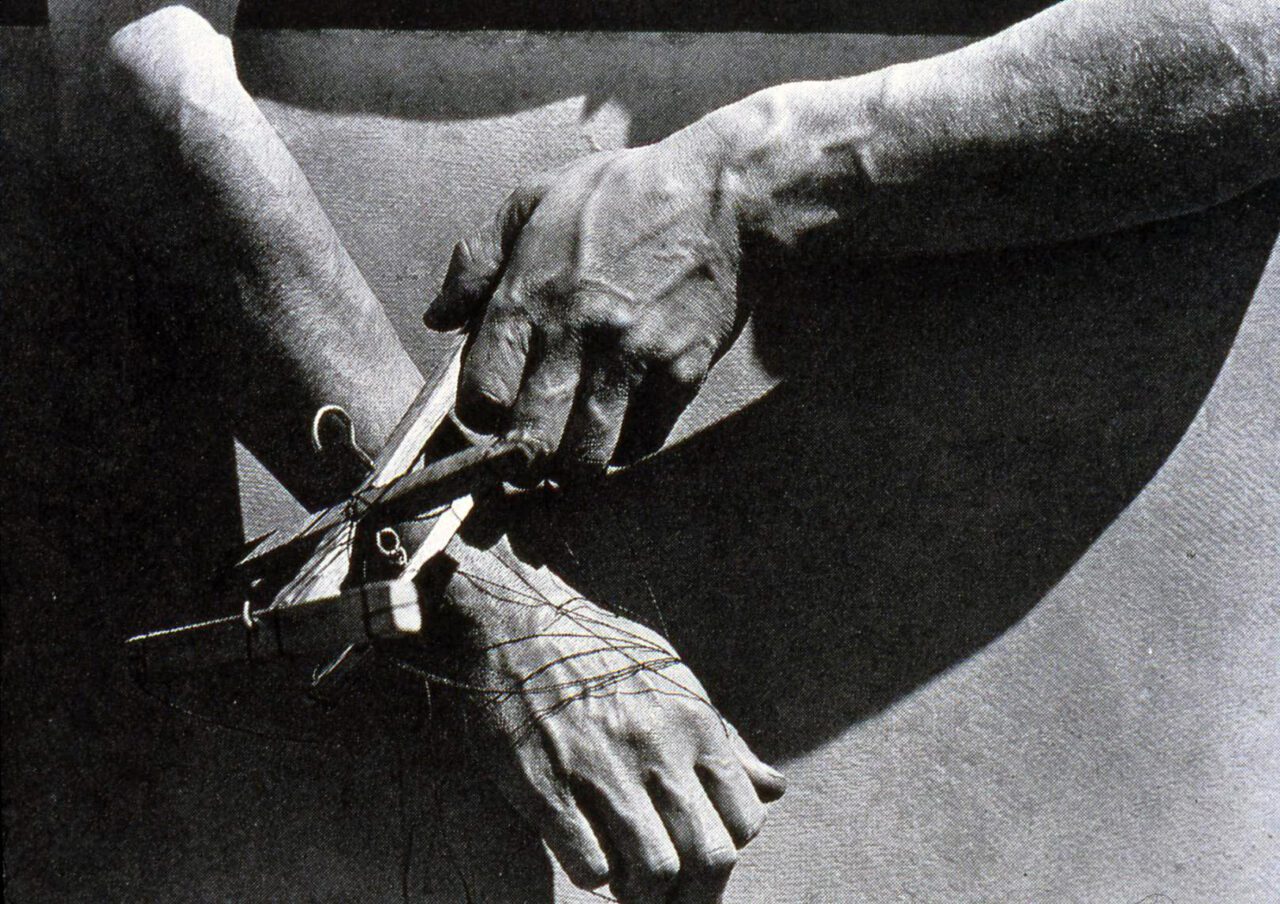

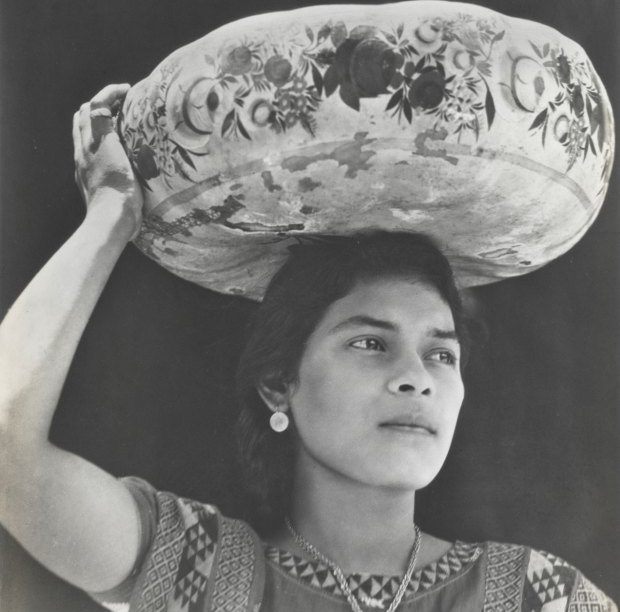

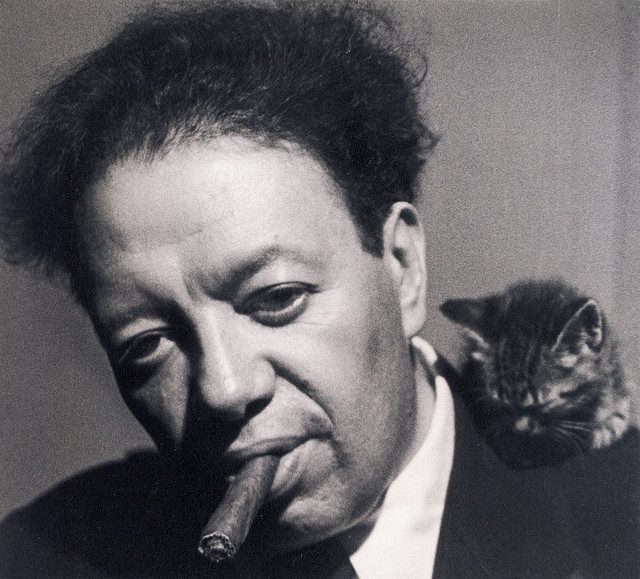

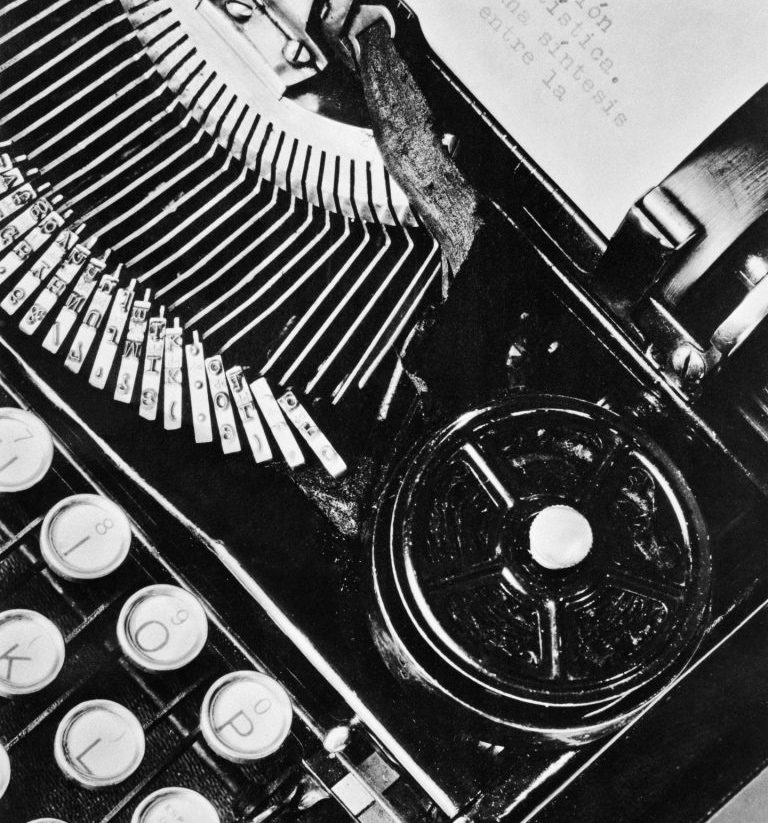

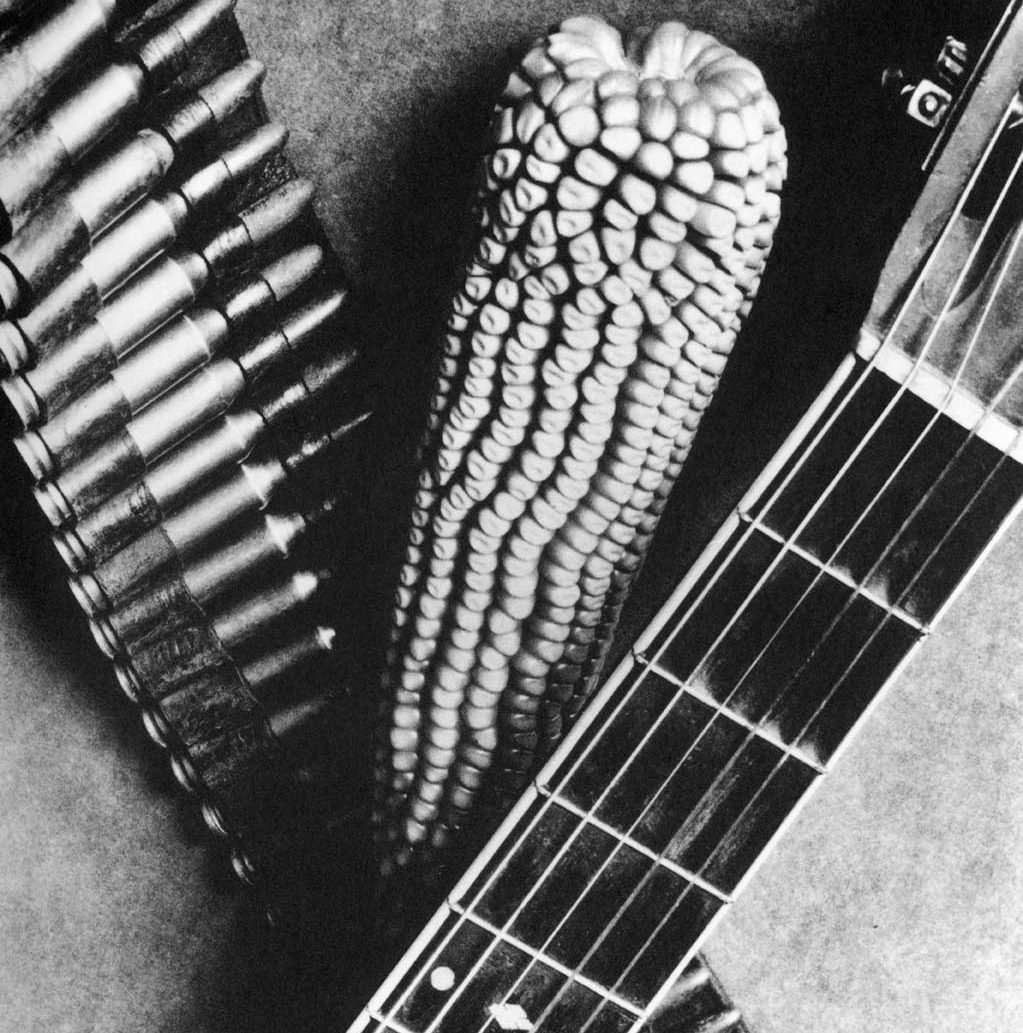

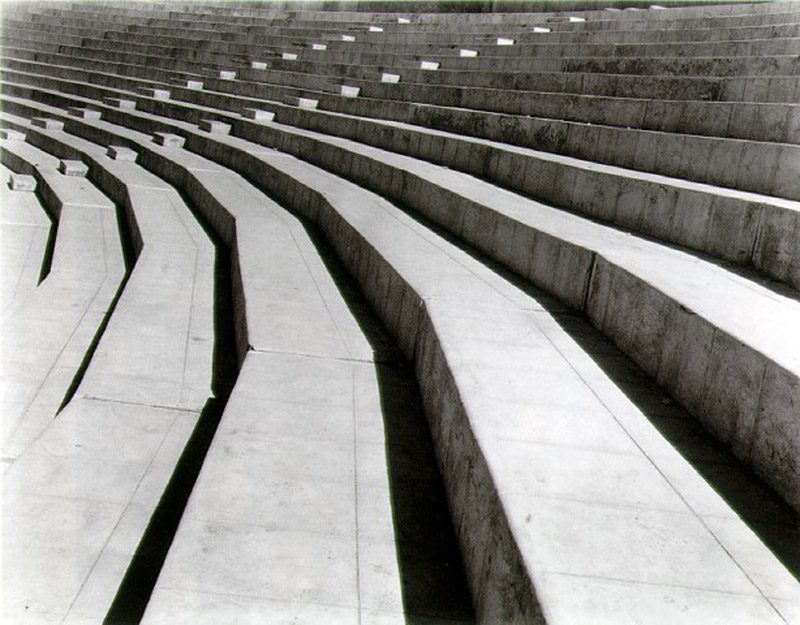

Tina Modotti (Assunta Adelaide Luigia Modotti) was n Udine, Friuli, Italy. In 1913, she immigrated to the United States to join her father in San Francisco, California. Attracted to the performing arts supported by the Italian community in the Bay Area, Modotti experimented with acting. She appeared in several plays, operas and silent movies in the late ‘10s and early ‘20s, and also worked as an artist’s model. In 1918, she married Roubaix “Robo” de l’Abrie Richey and moved with him to Los Angeles. There she met the photographer Edward Weston and his assistant Margrethe Mather. By 1921, Modotti was his favorite model and, by October of that year, his lover. Modotti’s husband seems to have responded to this by moving to Mexico in 1921. Following him to Mexico City, Modotti arrived two days after his death 9/2/22. In 1923 she and Weston moved to Mexico City and opened a portrait studio. Modotti first served as the studio manager, but after learning photography from Weston she became a full partner. It was also during this time that Modotti met several political radicals and Communists, including three Mexican Communist Party leaders who would all eventually become romantically linked with Modotti: Xavier Guerrero, Julio Antonio Mella, and Vittorio Vidali. Modotti’s early images include still lifes, architectural studies, and portraits. Following Weston’s lead, she worked from the premise that photographers should make full use of their medium’s unique capabilities. Her meticulously composed and finely detailed images of decontextualized objects, places, and people attest to his influence. The couple moved in the same circles as artists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, writer Anita Brenner, and other cultural figures. In 1926 Modotti documented murals by Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and other leading artists. Her pivotal 1926 photograph “Workers Parade” reflects her concern for class solidarity among Mexican workers. After joining the Communist Party in 1927, she made images such as “Mexican Sombrero with Hammer and Sickle”, symbolizing communist ideology and marrying formal elegance with highly charged political content. She collaborated with working-class people to create photographs intended to enhance their class consciousness and convey their dignity and worth. Her photographs for the communist newspaper El Machete were among the earliest examples of critical photojournalism in Mexico. Her visual vocabulary matured during this period, such as her formal experiments with architectural interiors, flowers and urban landscapes, and especially in her many lyrical images of peasants and workers. Indeed, her one-woman retrospective exhibition at the National Library in December 1929 was advertised as “The First Revolutionary Photographic Exhibition In Mexico”. She had reached a high point in her career as a photographer, but within the next year she was forced to set her camera aside in favor of more pressing concerns. In 1929 Modotti was framed for the murder of her companion, Julio Antonio Mella, a founder of the Cuban Communist Party. Though she was acquitted of the murder, Modotti was caught in a web of political intrigue. In 1930 she was jailed for her alleged participation in an attempted assassination of Mexican President Pascual Ortiz Rubio and was then deported from Mexico. She photographed briefly and without distinction in Berlin before moving to Moscow. There she more or less abandoned photography in order to devote her energies to International Red Aid, the Comintern’s international social service agency. Modotti became the companion of Italian Stalinist Vittorio Vidali, a suspect in Mella’s death. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Modotti traveled to Spain, where she undertook humanitarian and political work for International Red Aid in support of the Republican cause. Upon the fascist victory in 1939, she fled to France and then to Mexico. Modotti died from heart failure in Mexico City in 1942 under what is viewed by some as suspicious circumstances. After hearing about her death, Diego Rivera suggested that Vidali had orchestrated it. Modotti may have known too much about Vidali’s activities in Spain, which included a rumored 400 executions. Her grave is located within the vast Panteón de Dolores in Mexico City. Poet Pablo Neruda composed Tina Modotti’s epitaph, part of which can also be found on her tombstone, which also includes a relief portrait of Modotti by engraver Leopoldo Méndez. Modotti’s beauty, dramatic life, and active involvement in communist politics have often overshadowed her contributions to photography. Although her photographic career spanned only about seven years, she developed an original approach to political photography. Her images remain emblematic of postrevolutionary Mexico.

Tina Modotti (Assunta Adelaide Luigia Modotti) was n Udine, Friuli, Italy. In 1913, she immigrated to the United States to join her father in San Francisco, California. Attracted to the performing arts supported by the Italian community in the Bay Area, Modotti experimented with acting. She appeared in several plays, operas and silent movies in the late ‘10s and early ‘20s, and also worked as an artist’s model. In 1918, she married Roubaix “Robo” de l’Abrie Richey and moved with him to Los Angeles. There she met the photographer Edward Weston and his assistant Margrethe Mather. By 1921, Modotti was his favorite model and, by October of that year, his lover. Modotti’s husband seems to have responded to this by moving to Mexico in 1921. Following him to Mexico City, Modotti arrived two days after his death 9/2/22. In 1923 she and Weston moved to Mexico City and opened a portrait studio. Modotti first served as the studio manager, but after learning photography from Weston she became a full partner. It was also during this time that Modotti met several political radicals and Communists, including three Mexican Communist Party leaders who would all eventually become romantically linked with Modotti: Xavier Guerrero, Julio Antonio Mella, and Vittorio Vidali. Modotti’s early images include still lifes, architectural studies, and portraits. Following Weston’s lead, she worked from the premise that photographers should make full use of their medium’s unique capabilities. Her meticulously composed and finely detailed images of decontextualized objects, places, and people attest to his influence. The couple moved in the same circles as artists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, writer Anita Brenner, and other cultural figures. In 1926 Modotti documented murals by Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and other leading artists. Her pivotal 1926 photograph “Workers Parade” reflects her concern for class solidarity among Mexican workers. After joining the Communist Party in 1927, she made images such as “Mexican Sombrero with Hammer and Sickle”, symbolizing communist ideology and marrying formal elegance with highly charged political content. She collaborated with working-class people to create photographs intended to enhance their class consciousness and convey their dignity and worth. Her photographs for the communist newspaper El Machete were among the earliest examples of critical photojournalism in Mexico. Her visual vocabulary matured during this period, such as her formal experiments with architectural interiors, flowers and urban landscapes, and especially in her many lyrical images of peasants and workers. Indeed, her one-woman retrospective exhibition at the National Library in December 1929 was advertised as “The First Revolutionary Photographic Exhibition In Mexico”. She had reached a high point in her career as a photographer, but within the next year she was forced to set her camera aside in favor of more pressing concerns. In 1929 Modotti was framed for the murder of her companion, Julio Antonio Mella, a founder of the Cuban Communist Party. Though she was acquitted of the murder, Modotti was caught in a web of political intrigue. In 1930 she was jailed for her alleged participation in an attempted assassination of Mexican President Pascual Ortiz Rubio and was then deported from Mexico. She photographed briefly and without distinction in Berlin before moving to Moscow. There she more or less abandoned photography in order to devote her energies to International Red Aid, the Comintern’s international social service agency. Modotti became the companion of Italian Stalinist Vittorio Vidali, a suspect in Mella’s death. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Modotti traveled to Spain, where she undertook humanitarian and political work for International Red Aid in support of the Republican cause. Upon the fascist victory in 1939, she fled to France and then to Mexico. Modotti died from heart failure in Mexico City in 1942 under what is viewed by some as suspicious circumstances. After hearing about her death, Diego Rivera suggested that Vidali had orchestrated it. Modotti may have known too much about Vidali’s activities in Spain, which included a rumored 400 executions. Her grave is located within the vast Panteón de Dolores in Mexico City. Poet Pablo Neruda composed Tina Modotti’s epitaph, part of which can also be found on her tombstone, which also includes a relief portrait of Modotti by engraver Leopoldo Méndez. Modotti’s beauty, dramatic life, and active involvement in communist politics have often overshadowed her contributions to photography. Although her photographic career spanned only about seven years, she developed an original approach to political photography. Her images remain emblematic of postrevolutionary Mexico.