PRESENTATION: Jaune Quick toSee Smith-Memory Map

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith is an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and is also of Métis and Shoshone descent. For nearly five decades, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, has charted an exceptional and unorthodox career as an artist, activist, curator, educator, and advocate. The exhibition highlights how Smith uses her drawings, prints, paintings, and sculptures to flip commonly held historical narratives and illuminate absurdities in the dominant culture.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith is an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and is also of Métis and Shoshone descent. For nearly five decades, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, has charted an exceptional and unorthodox career as an artist, activist, curator, educator, and advocate. The exhibition highlights how Smith uses her drawings, prints, paintings, and sculptures to flip commonly held historical narratives and illuminate absurdities in the dominant culture.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Whitney Museum Archive

“Memory Map” is the largest and most comprehensive showcase of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s career, featuring more than one hundred thirty works. Organized thematically the exhibition offers a new framework to consider contemporary Native American art, addressing how Smith has led and initiated some of the most pressing dialogues around land, racism, and cultural preservation. It celebrates the artist’s dedication to creativity and community and emphasizes her deep political commitments, essential and potent reminders of our responsibilities to the earth and each other. Smith engages with modern and contemporary modes of artmaking, from an idiosyncratic adoption of abstraction to American Pop art to Neo-Expressionism. She reimagines these artistic traditions with concepts rooted in her own cultural practice to examine contemporary life in America and interpret it through Native ideology. Since the 1970s, Smith has built a visual language that includes recurring imagery, such as trade canoes, horses, bison, and flags, and common materials like newspaper, fabric, and commercial objects. Throughout her works, she addresses urgent concerns of ecological disaster, the misreading of history, and the genocide of Native Americans, while also evoking the power of kinship and education. “The exhibition highlights the artist’s lifelong approach to storytelling, rooted in her abiding respect for and connection to the land in these sections. Early Work: Smith knew from an early age that she wanted to be an artist but was discouraged early on by professors who didn’t believe women (much less Native women) could have careers as artists. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Smith drew and painted places with personal significance, including Wallowa, Oregon, and her reservation. These works, which she came to describe as maps, reject conventions employed by Western landscape painters. Instead of romanticized panoramas that survey unpopulated lands from a distance, Smith depicts inhabited places, her mark-making conveying human and animal movements. Many of the early works exhibited in Memory Map, like Indian Madonna Enthroned (1974), have rarely been on view to the public.

Dedication to Land: Between 1985 and 1989, Smith concentrated on two series that highlight her role as an activist and artist: “Petroglyph Park” and “Chief Seattle (C.S.)”. Despite their stylistic differences, both bodies of work demonstrate Smith’s engagement with ongoing land rights conflicts and historical injustices. Smith became active in land preservation efforts and supported campaigns to save areas of New Mexico where ancient petroglyphs were at risk of being destroyed due to residential development efforts. “Petroglyph Park” is the first series in which Smith responded directly to news media, an approach that has since been integral to her practice. Works in the “Chief Seattle (C.S.)” series continue the artist’s critique of reckless extraction and industrialization and consider broader regional and global environmental concerns such as acid rain and dependence on fossil fuels. While mainstream environmentalism at the time concentrated on issues like pollution and recycling, Smith’s work draws a connection between the exploitation of land and resources with blatant disregard for treaties between the U.S. government and Native American nations. Depictions of a Postcolonial World: In response to the 1992 U.S. quincentennial celebration of Christopher Columbus landing in the Americas, Smith sought to bring attention to the fact that Columbus’s arrival led to one of the largest and most sustained genocides in human history. This period marks some of Smith’s most prolific work as an artist, curator, and collaborator. She created dozens of new artworks and organized exhibitions and “anti-celebration” events with her peers. Though her politics had always been embedded in her work, this particular moment in American history became Smith’s opportunity to develop more direct and transparent approaches in her work. She introduced many of her now iconic motifs, like the trade canoe and bison, and techniques like collage. Works in this section, such as “I See Red: Snowman” (1992) confront the violence of displacement and the extreme inequities of the earliest negotiations between Indigenous peoples and settlers in North America.

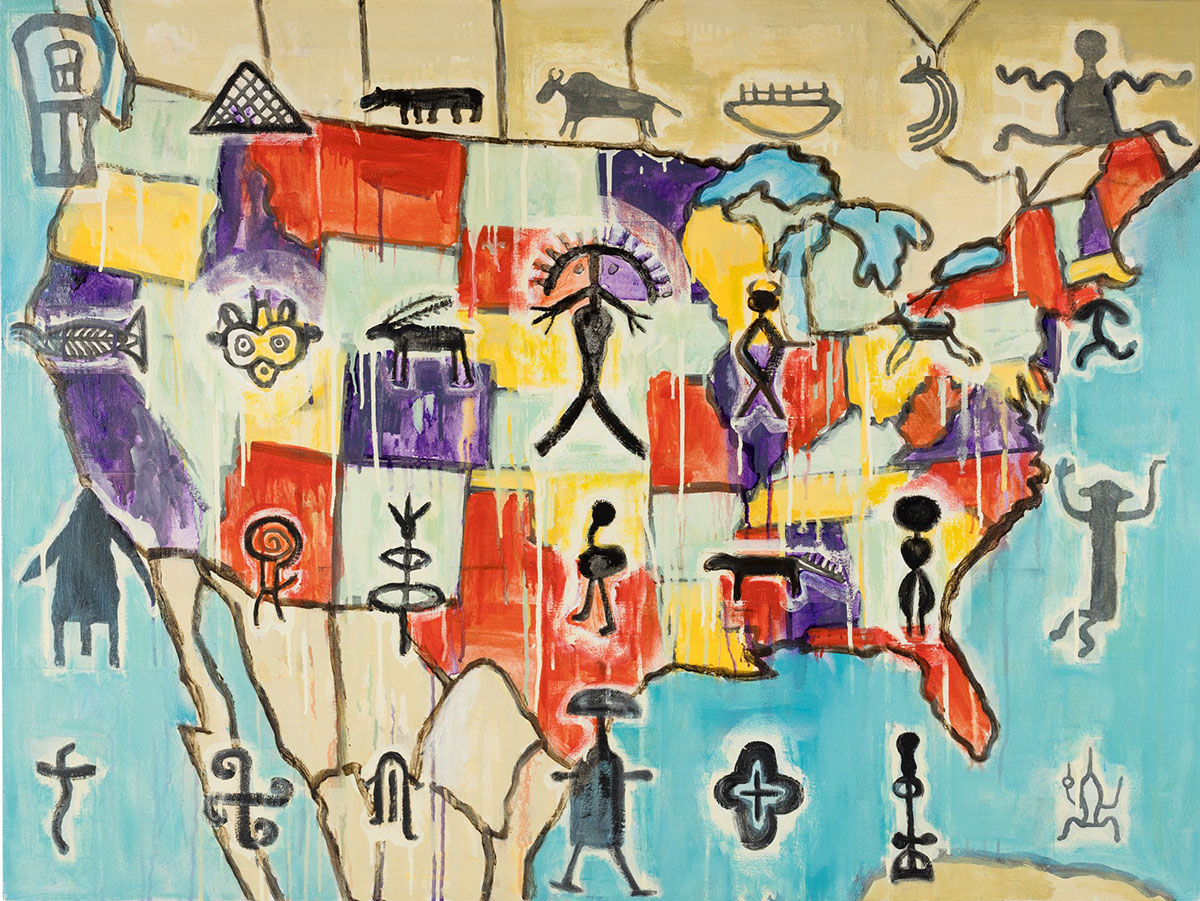

Reflections on Invasion: Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, in response to U.S.-led invasions domestically and abroad, Smith’s work considers the conflicts incited by both colonialism and imperialism. A 1993 series of prints and drawings depict a well-known image of General George Armstrong Custer, the U.S. Army officer known for his deadly campaigns against Lakota, Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne people in the late 1860s. Moving forward in time, paintings and prints from the 2000s communicate Smith’s outrage over the invasion of Iraq and President George W. Bush’s post-9/11 policies. Smith’s work from this period conveys her visceral and consuming reaction to the horrors of war. Paintings like “Trade Canoe for Don Quixote” (2004) use art historical references like Picasso’s “Guernica”, images of Sumerian artifacts looted from the Iraq Museum, and political cartoons by José Guadalupe Posada, to highlight how cultural property is targeted and weaponized in these conflicts. Critiques of Capitalism and Consumerism: In recent decades, Smith’s work offers a biting critique of the elements of American culture dominated by capitalism and consumerism. Frequently employing satire and humor in her paintings and prints, Smith has targeted the imported concepts of property and commodity goods, which decimated Indigenous economies, diets, and medicinal practices. She has also taken aim at manifest destiny, an Anglo-Christian doctrine that positioned westward expansion and the attempted extermination of Indigenous peoples as part of a divine plan. The repercussions of these policies live on in the many ways that contemporary consumer culture has infiltrated Native American traditions. In works like “The Rancher” (2002), Smith draws connections between visual tropes of the “Wild West,” like the “cowboys and Indians” seen in advertising and entertainment, and the seemingly unlimited reach of corporate influences in even the smallest and most personal experiences of contemporary daily life. Legacy and Matriarchy: Smith often makes a simple but profound observation: “My existence is a miracle.” Despite genocide, decades of war, forced assimilation, and systemic oppression, she and other Indigenous survivors are still here to practice and share their culture. Throughout her work, Smith acknowledges that the wisdom of ancestors and elders is not only sacred but essential for protecting and preserving traditions for future generations. Throughout her career, Smith has represented matriarchal leaders across many works, conveying the individuality and strength of women who juggle their responsibilities to family and community in the face of prejudice and discrimination. U.S. Maps: The map of the United States is one of the most central and recognizable motifs throughout Smith’s paintings, drawings, and prints. Her works reveal the falsehoods and assumptions underlying this supposedly objective image, challenging its authority and symbolic power. In Smith’s interpretations of the map of North America, the land transgresses and overruns current borders, demonstrates changing populations and notions of citizenship, and foregrounds how Indigenous peoples have shaped this continent since long before the European invasion. Smith’s works reflect her philosophy of maps: they are pictures of experiences rather than edges of geopolitical borders–an understanding of land that privileges relationships, stories, and memory. Environment and Intervention: The industry and government abuse and mismanagement of the environment have been key concerns in Smith’s work throughout her career. As the artist has said, “ecology is a science that has been practiced by the Native peoples on this continent for thousands of years. For instance, in my tribe, after harvesting the bitterroot for the spring feast, there is the specific act of cleaning the bitterroot plants to ensure next year’s crop. This is giving back. This has been our way of survival.” Trickster: Smith’s art continues the storytelling tradition she grew up with. From an early age, she heard the creation stories of the Salish people from her grandmothers and aunts. Coyote plays an important role in these stories. First sent by the Creator to prepare the earth for humans, Coyote taught the Salish about spirituality and the sacred relationship of people to the land and all living creatures. But Coyote is also a trickster whose lessons reveal the chaos and hubris of human lives and actions. Smith embraces the duality of teacher and trickster in her artistic practice.

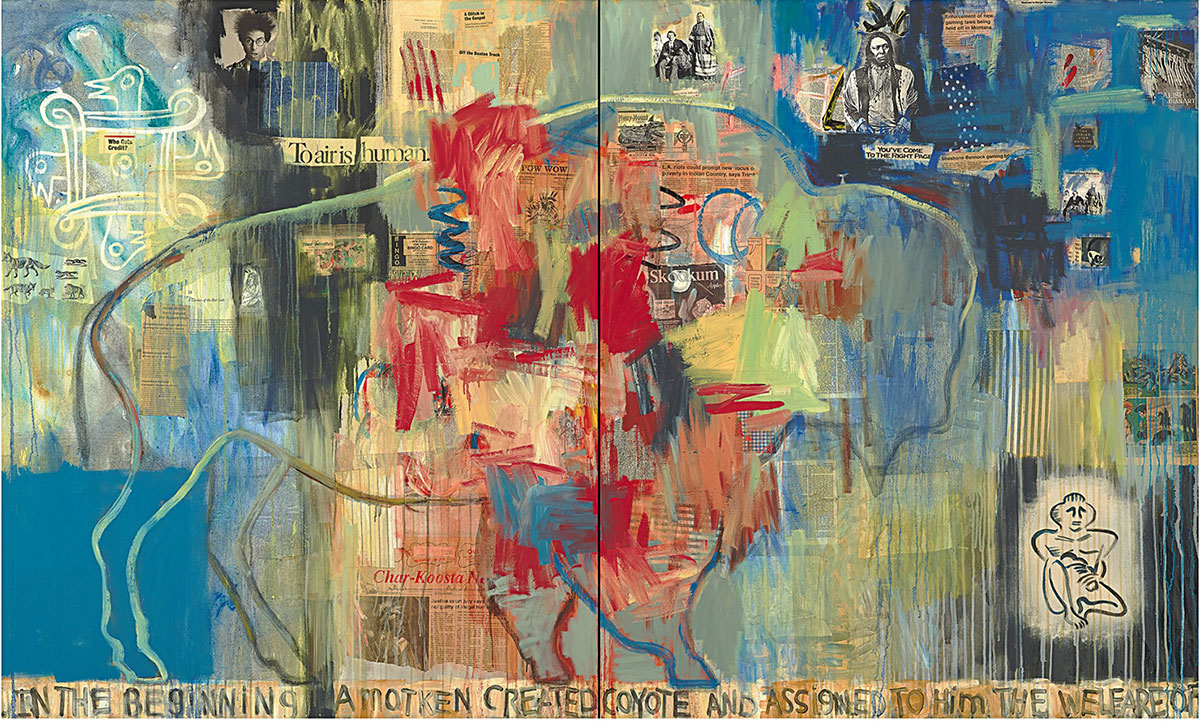

Photo: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Genesis, 1993. Oil, paper, newspaper, fabric, and charcoal on canvas, two panels: 60 × 100 in. (152.4 × 254 cm) overall. High Museum of Art, Atlanta; purchase with funds provided by AT&T NEW ART/NEW VISIONS and with funds from Alfred Austell Thornton in memory of Leila Austell Thornton and Albert Edward Thornton, Sr., and Sarah Miller Venable and William Hoyt Venable. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Photograph courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Info: Curators: Laura Phipps and Caitlin Chaisson, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street. New York, NY, USA, Duration: 19/4-13/8/2023, Days & Hours: Mon, Wed-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-18:00, Fri 10:30-22:00, https://whitney.org/

Right: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Survival Suite: Humor, 1996. Lithograph with chine collé, 36 1/8 × 24 13/16 in. (91.8 × 63 cm). Printed by Lawrence Lithography Workshop; published by Zanatta Editions. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Joe and Barb Zanatta Family in honor of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith 2003.28.2. © Jaune Quick-to-See

Right: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Survival Suite: Tribe/Community, 1996. Lithograph with chine collé, 36 1/16 × 24 7/8 in. (91.6 × 63.2 cm). Printed by Lawrence Lithography Workshop; published by Zanatta Editions. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Joe and Barb Zanatta Family in honor of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith 2003.28.2. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith