PRESENTATION: Ursula-That’s Me. So What?

Ursula Schultze-Bluhm or simply known as Ursula, painter of unearthly visions, was largely overlooked by the art world. Years after her death, she’s getting a major retrospective. For a half-century, the German artist Ursula Schultze-Bluhm made work that could astonish viewers. One critic proposed that she “would not have been allowed to paint in the Middle Ages” and “would have been burned.”

Ursula Schultze-Bluhm or simply known as Ursula, painter of unearthly visions, was largely overlooked by the art world. Years after her death, she’s getting a major retrospective. For a half-century, the German artist Ursula Schultze-Bluhm made work that could astonish viewers. One critic proposed that she “would not have been allowed to paint in the Middle Ages” and “would have been burned.”

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museum Ludwig Archive

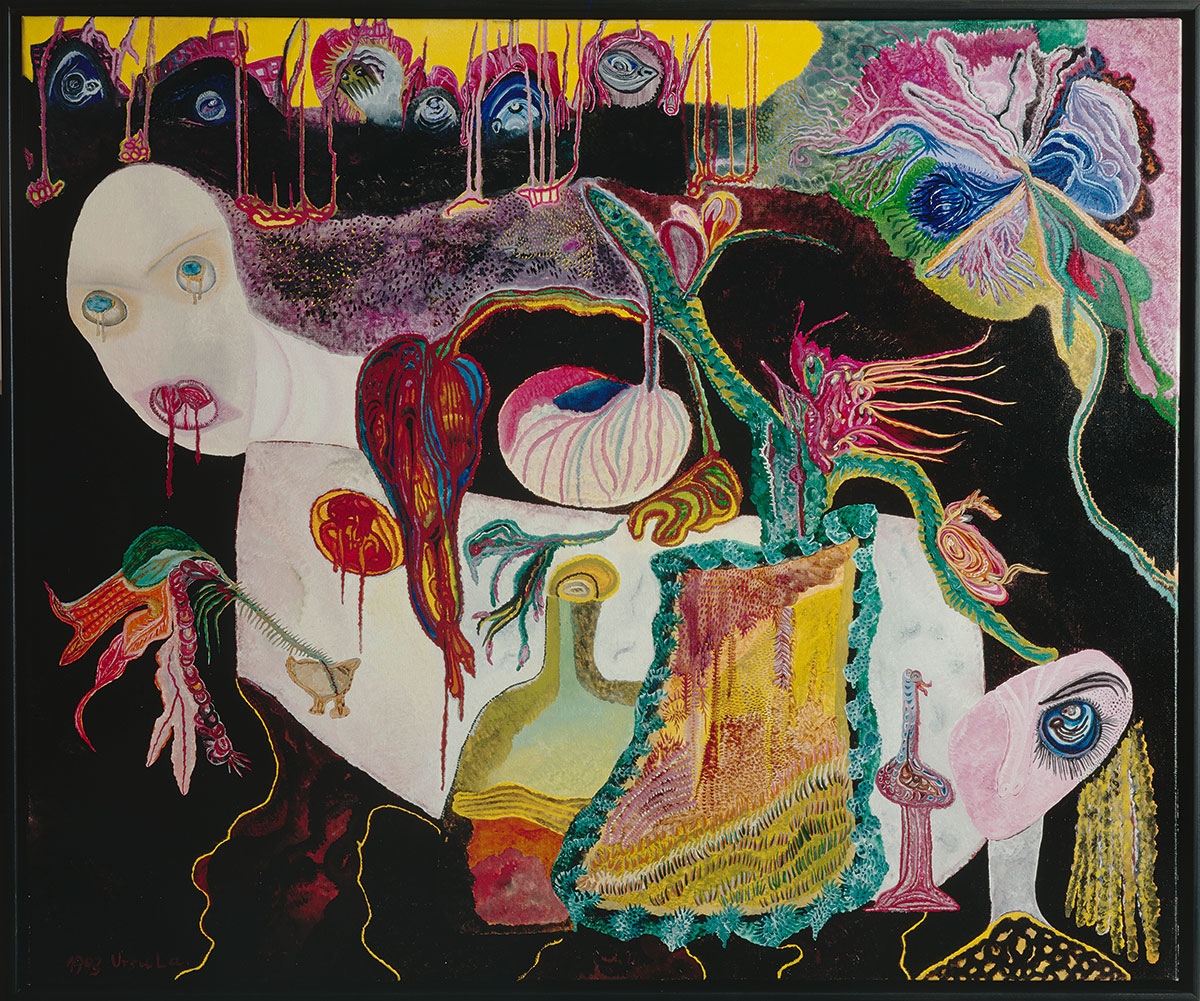

Ursula was one of the most important German artists of the second half of the twentieth century. She was born in Mittenwalde, Germany, in 1921 and died in Cologne in 1999. With 236 works, the exhibition “Ursula—That’s Me. So What?”, which is the first comprehensive museum show on the artist in over thirty years, offers a fresh look at her oeuvre. Ursula’s life and work offer an unconventional narrative of artistic independence. Her art exemplifies the idea that Surrealism is not a style, but an attitude. Ursula subverted reality and found the uncanny in the everyday, challenging the authorities of society and art by imagining new worlds in which old hierarchies are thrown overboard and new ways of life are conceivable. Ursula shared this utopian imagination with artists such as Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning, and Unica Zürn. Her sinuous, wildly colored compositions, which she built with patterns of dots and lines, suggest deep-space marvels or activity under a microscope, with mysterious beings that dance, fly and metamorphose. Monstrous faces float across a black expanse in “Nightmares” (1961), while “The Unicorn” (1983) has the mythical animal growing from the thigh of a strange, humanoid entity. “The more fantastic, the more real they are,” she once said of her work. It is impossible to unambiguously categorize the essence of Ursula’s works. Terms such as naive painting, Surrealism, or individual mythology only touch on individual aspects of her unorthodox visual ideas, which always convey an intensely sensual experience. Jean Dubuffet integrated works by Ursula in his Musée de l’Art Brut as early as 1954. Like André Breton, Dubuffet appreciated the unconventional narrative style of her texts and pictures, which, at least on first glance, seem to stand outside of time. While they often refer to mythology, they usually reflect the artist’s own emotional states, fears, and obsessions. “I impose my visions on reality—I am completely artificial,” Ursula declared, characterizing her unusual parallel worlds in which extravagant characters exist and the familiar and the uncanny are perceptible. Beauty and transience, the fairy-like and the monstrous, thrive side by side. One of Ursula’s characteristic subjects was Pandora, the woman who was created from clay in Greek mythology, in whose story the most terrible evils and the most excellent gifts are inseparably intertwined. Ursula’s scenes are frequently inhabited by fantastical hybrid creatures, and the allure of transformation is tangible everywhere, challenging time-worn dualisms such as woman/man and human/nature. This overview exhibition at the Museum Ludwig aims to present Ursula’s captivating and self-assured work to a new generation of museum visitors. The show reveals that it is the individuality of Ursula’s work that allows it to touch on so many fundamental and topical issues, including female self-determination and the challenging of established gender identities, with a worldview in which everything is interconnected and mutually dependent.

Photo: Ursula, URSULA FUR HOUSE, 1970, WV (70/101), Oil on wood, fur, feathers, mirrors, iron, various objects, 315 x 250 x 204 cm, on base 600 x 600 cm, Märkisches Museum Witten, © Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

Info: Curator: Stephan Diederich, Curatorial assistant: Helena Kuhlmann, Museum Ludwig, Heinrich-Böll-Platz, Cologne Germany, Duration: 18/3-23/7/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.museum-ludwig.de/