PRESENTATION: Laurie Anderson-Looking Into A Mirror Sideways

Laurie Anderson is a legendary figure within US avant-garde art, experimental music, and independent culture. Equal parts performer, author, composer, activist, and filmmaker, her work cuts through gen-res. She achieved her international breakthrough as a pioneer of electronic music. Today she works at the cutting edge of new arts technologies, like VR and AI – but is just as likely to employ timeless expressions like voice, painting, or charcoal drawings.

Laurie Anderson is a legendary figure within US avant-garde art, experimental music, and independent culture. Equal parts performer, author, composer, activist, and filmmaker, her work cuts through gen-res. She achieved her international breakthrough as a pioneer of electronic music. Today she works at the cutting edge of new arts technologies, like VR and AI – but is just as likely to employ timeless expressions like voice, painting, or charcoal drawings.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Moderna Museet Archive

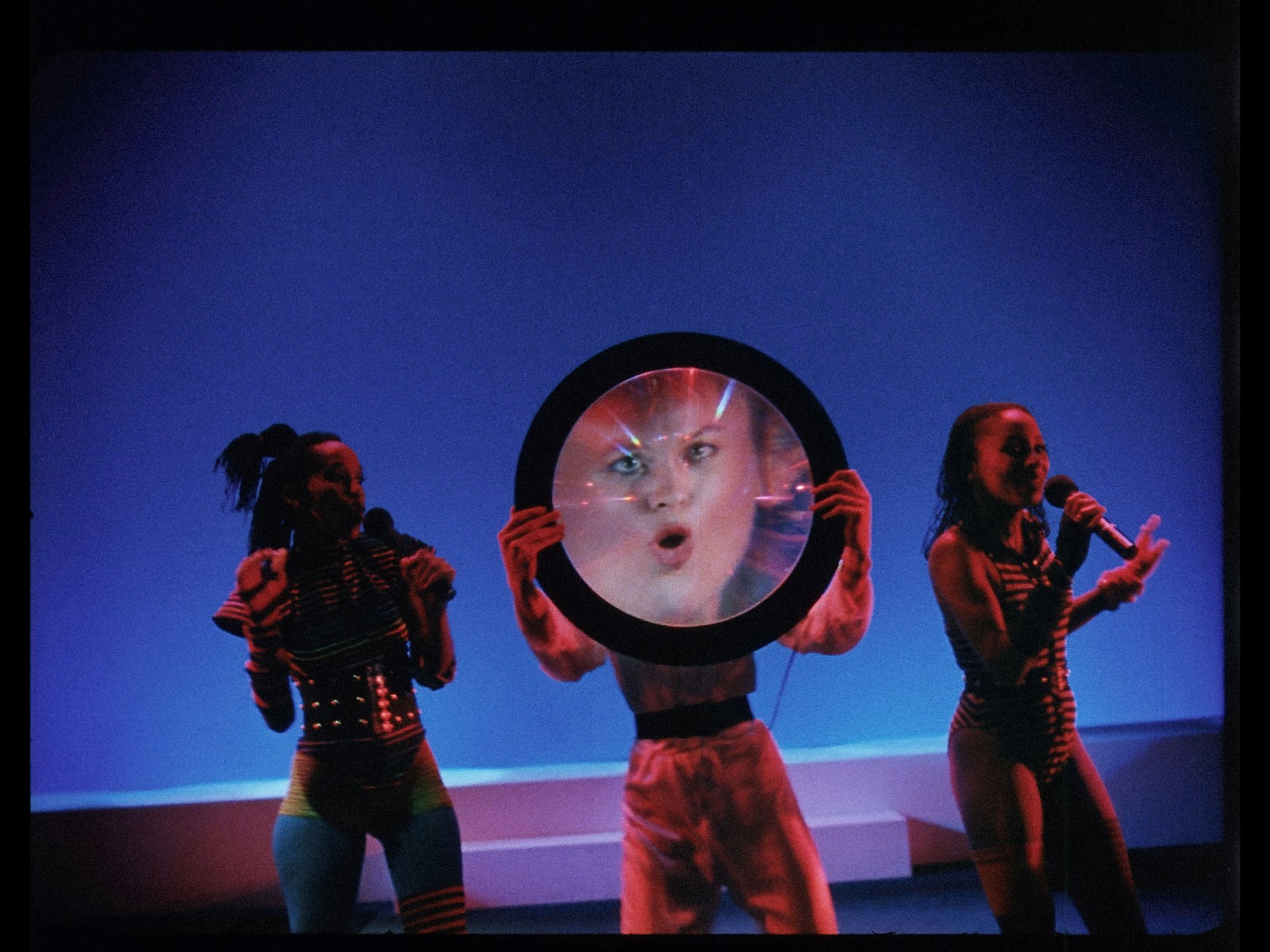

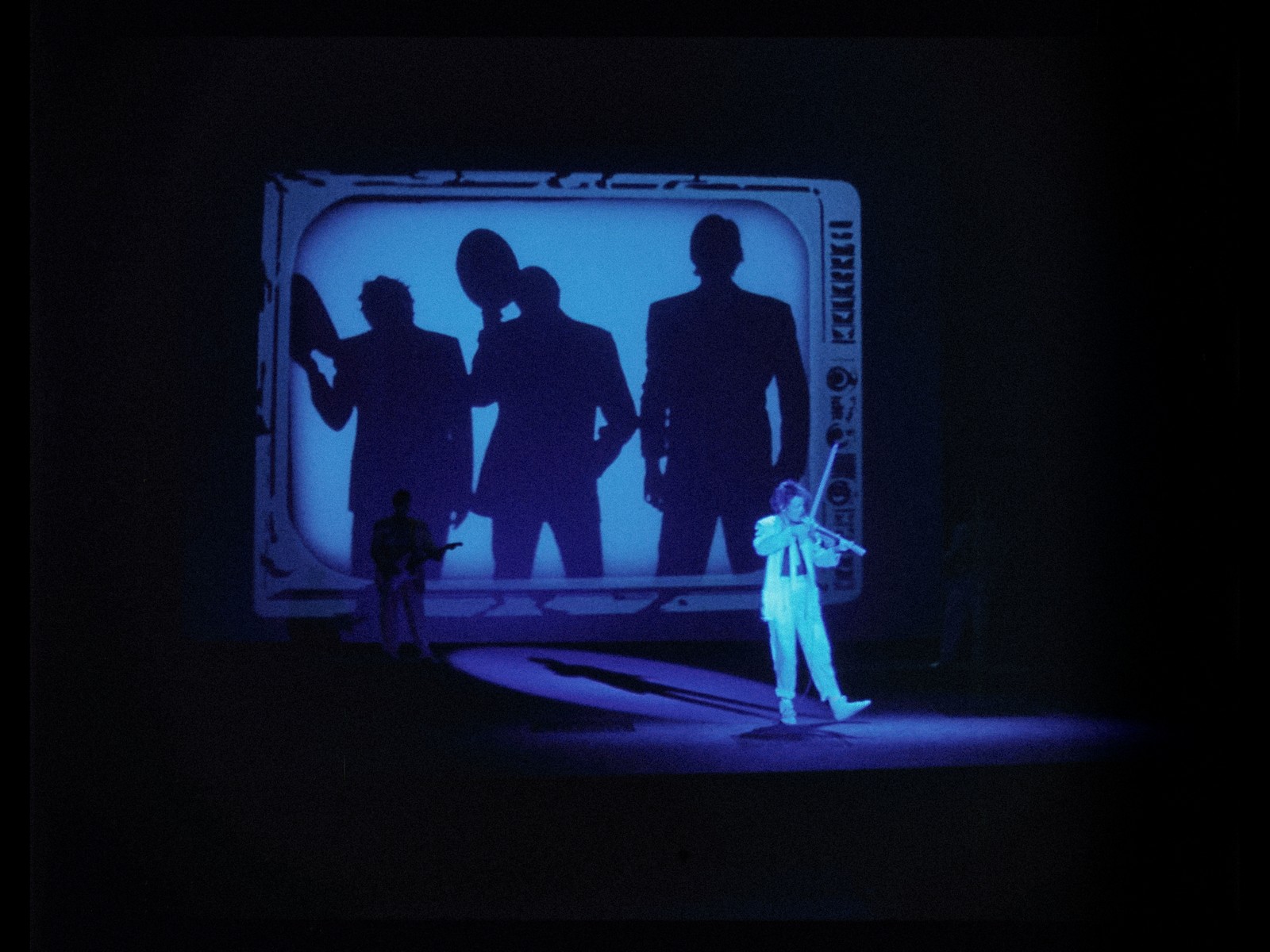

In “Looking into a Mirror Sideways”, Laurie Anderson’s largest solo exhibition to date in Europe, visitors are treated to a narrative on the nature of time, space and existence. A representative selection of the artist’s works from the 1970s up to the present day is complemented with brand new, site-specific productions: conceptual art, performance, innovative musical instruments, compositions, stage shows, as well as activist art and political art. The exhibition serves as a forum for both physical materials and techniques – painting, sculpture, analogue photography, sound tapes and film strips – and new digital worlds, such as virtual reality. The exhibition combines new site-specific productions with selections from the artist’s oeuvre, including performance, photography, and video. In several works Anderson explores issues of subject and of identity, the roles we take and are given, for example, via the artist’s Swedish-born paternal grandfather, Axel Efraim Anderson. Music and voice are the foundation of Laurie Anderson’s work. Speech, pauses, and even the act of listening, are all central to her compositions and performances. Anderson has experimented with site-specific sound works since the 1970s. Her compositions are influenced by geometry and language, as well as every-day sounds. Over time she has been combining music with performance, film, and technical innovation, culminating in multimedia stage productions like “United States I–IV” (1983) or the opera “Moby Dick” (1999). She has also developed new instruments. In “Tape Bow Violin”, the horsehair in the bow is replaced by audio tape. The voice on the recording is transformed into repetitive sounds, words void of meaning even as they carry the soundscape. In “Drum Suit” the body becomes an instrument, with parts of a drum machine sewn into overalls, in “Drum Glasses” the cranium becomes a sound box. The 1990s high-tech work “Talking Stick” samples sounds from the stage that are replayed in a new form. In “Citizens”, the room is filled with the metallic sound of figures sharpening knives, each to their own rhythm. An abstract sound piece that doubles as a portrait of friends, and a snapshot of the charged atmosphere around the US election year of 2020 portrait of friends, and a snapshot of the charged atmosphere around the US election year of 2020. In “To the Moon”, Anderson employs VR technology to transport us to a place beyond the physical world. Participants are sent on a dreamlike exploratory journey across the moon’s enigmatic surface. References to Greek mythology, literature, science, film, and politics flash by in an experience that offers perspectives on our still living but vulnerable planet. Space is another recurring theme in Anderson’s work; in 2002 she was invited by NASA as the US space agency’s first artist-in-residence. “To the Moon” is a collaboration with Taiwanese artist Hsin-Chien Huang. In the aftermath of 9/11 Anderson staged a manifestation in collaboration with Mohammed el Gharani (b. 1986). As the youngest prisoner at the Guantánamo Prison – accused of plotting a terrorist attack at the age of 12, he was released and deported from the US in 2009, without any valid citizenship. The work’s title, “Habeas Corpus”, is the legal principle meant to protect against arbitrary imprisonment. During a New York City concert with Anderson in 2015, the stateless refugee met the public in a monumental livestream to tell his story from a studio in Ghana. The work highlights a political situation that turns individuals into pawns in a game, but also the nightmare of being robbed of one’s identity, time, and memories. While Anderson frequently uses technology, she tells her stories in other ways as well. In 2011, the death of her dog, Lolabelle, triggered a series of works including her 2015 film “Heart of a Dog”, which explored her childhood and the deaths of her mother and Lolabelle. Anderson, a practicing Buddhist, imagined her dog in the Bardo (in which, according to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, all living things must spend 49 days in preparation for reincarnation). Anderson’s large-scale charcoal drawings of Lolabelle’s journey are vast and gestural, open in a way that makes you feel like you can leap inside of them, like no-tech virtual reality. We stand with Lolabelle witnessing both chaos and calm. “Lolabelle in the Bardo, April 18” is a vortex of energy, the dog hardly present. In the other hand, “Lolabelle in the Bardo, May 5”, functions like a stock of memories, depicting multiple versions of the dog including one of Lolabelle playing the keyboard (a task she was taught late in life to combat boredom as her eyesight failed). In each drawing Anderson includes a Tibetan prayer wheel, always spinning like a dervish, symbolizing the cyclical nature of life and the stories we tell each othe Laurie Anderson has said that she speaks in order to understand the world. Her stories mine her own observations and experiences, but they also draw on literary works, mythology, and new science. A story might expand and become a full stage production, like in the case of her latest opera “ARK”. Set to premier in Manchester in 2024, the work is based on the Bible story of Noah’s ark, another theme that Anderson has used in multiple contexts. The flood in “ARK” is, however, not a punishment for man’s sins like in the Bible story, but rather the result of iCloud bursting, and humanity’s collected know-ledge being lost as it rains down over Earth. A host of art-historical and contemporary figures and phenomena feature in this epic, which offers more questions than answers. Buddha argues with Christianity’s stricter God about how to save the world – or, whether the apocalypse is in fact the ultimate goal and meaning of everything. For Moderna Museet, Anderson stages a number of scenes from ARK as spatial installations.

Photo: Laurie Anderson, Heart of a Dog, 2015, Film still, © Laurie Anderson

Info: Curator: Lena Essling, Moderna Museet, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, Sweeden, Duration: 1/4-3/9/2023, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri 10:00-20:00, Wed-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.modernamuseet.se/

Concert film of Laurie Anderson performing songs from her first three albums, selections from her four-night epic “United States Live,” and several new songs, incorporating film, animation, dance, and electronics