PRESENTATION: Mona Hatoum-Early Works

Mona Hatoum’s work dialogues, in an original and exemplary manner, with the major disciplines and Movements of contemporary art: Performance, Video, Kinetic Art, Minimalism and Conceptual art. The strength of her work comes from the feeling it induces in viewers. She leaves them to navigate through an unstable universe, a world driven by contradictions and unfolding in different time frames, characterized by tensions. Mona Hatoum often places viewers at the heart of the work, engaging them in dialogue, sometimes putting them to the test.

Mona Hatoum’s work dialogues, in an original and exemplary manner, with the major disciplines and Movements of contemporary art: Performance, Video, Kinetic Art, Minimalism and Conceptual art. The strength of her work comes from the feeling it induces in viewers. She leaves them to navigate through an unstable universe, a world driven by contradictions and unfolding in different time frames, characterized by tensions. Mona Hatoum often places viewers at the heart of the work, engaging them in dialogue, sometimes putting them to the test.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MCA Chicago Archive

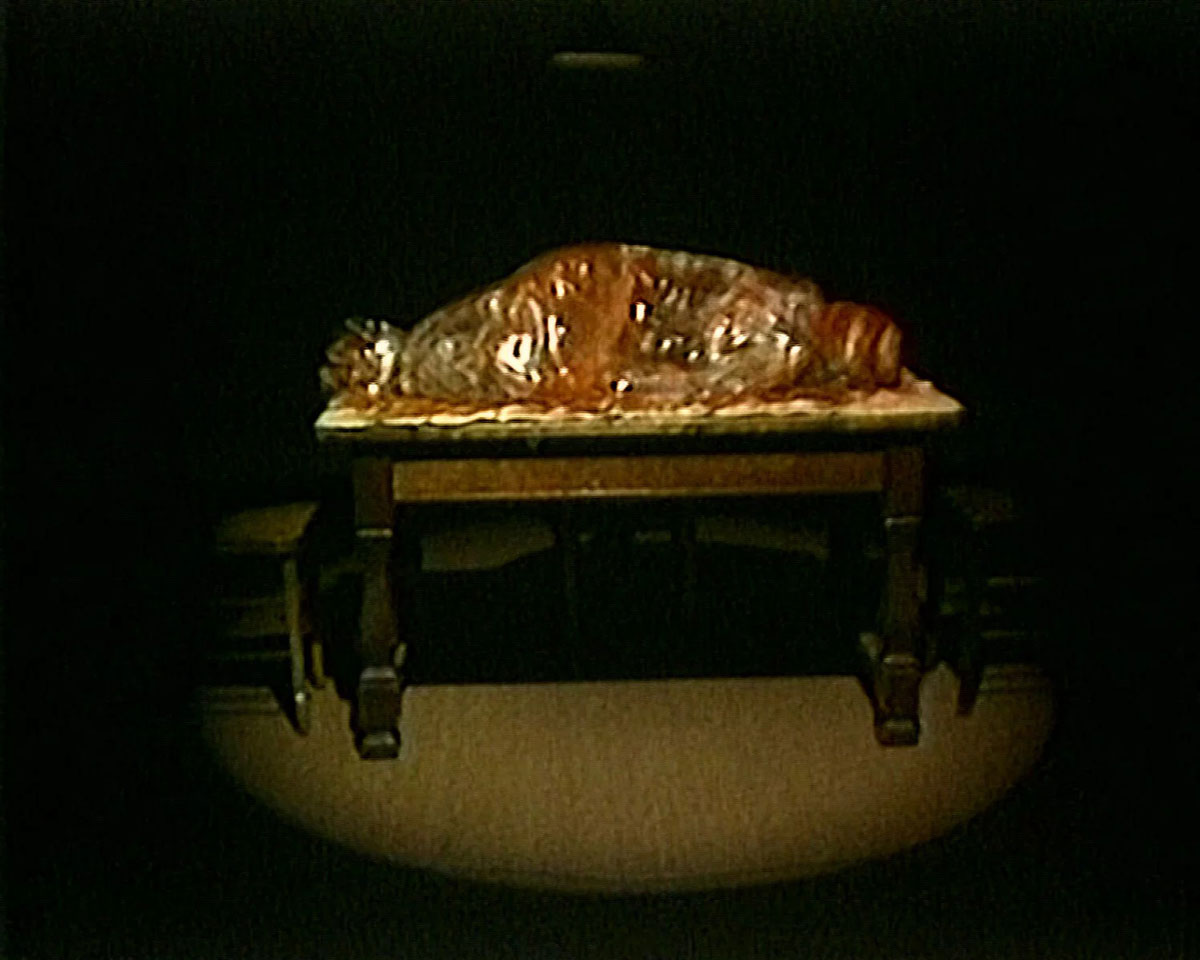

Early in her career, Mona Hatoum used a combination of media to pointedly reflect on power and how it is used. The exhibition “Mona Hatoum: Early Works” presents a selection of documented performances and video works from that formative stage of Hatoum’s career. Hatoum’s work from this period reaches across international, personal, and political contexts to address complex ideas that still resonate today. Among Hatoum’s key concerns are the politics imposed on women’s bodies, the relationship between spectators and subjects, and connections among globally marginalized communities. This exhibition, which includes highlights from the MCA collection, revisits the early practice and foundational works of a prolific artist, 25 years after the MCA hosted her first solo exhibition in the United States. Hatoum started her career in the 1980s making visceral video and performance work that focused intensely on the body. Since the early 1990s, however, she has increasingly created large-scale installations that aim to engage the viewer in conflicting emotions of desire and revulsion, fear and fascination. The performance “Negotiating Table” (1983) was an explicit response to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon that took place in 1982. Mona Hatoum lay motionless on a table for several hours, blindfolded. She was enclosed in a plastic bag, covered with blood, her feet bound with a rope, carrying entrails stuck to her chest. Some empty chairs. A single light bulb illuminated her. One could hear a flow of news reports of the war and leaders in peace negotiations. The Western Front — where Hatoum was an artist-in-residence in 1984 — hosted what is considered as her most overtly political performance. Hatoum made “Changing Parts” (1984) during a year’s residency at Western Front Art Centre in Vancouver, Canada. It operates through the juxtaposition of two strands of ambiguously contrasting image and sound. Material for one part of the video was derived from super-8 footage of a seven hour performance Hatoum made in 1982 at the London Film Makers Co-op and Aspex Gallery, Portsmouth, titled “Under Siege” in which she moved around in a transparent plastic cubicle-like container filled with mud. In “Changing Parts” grainy freeze-frame images of the artist’s face and mouth as she struggles to bite and tear her way out of the mud-smeared plastic membrane are intercut with a series of black and white photographs of a bathroom interior. These were taken in the bathroom in Beirut while Hatoum was visiting her family. The video begins with the tranquil bathroom photographs accompanied by Bach’s “Cello Suite No.4.” This mood is abruptly shattered by the disorientating cacophony of street noise and half-audible news reports which accompany the images from “Under Siege”, providing a claustrophobic and visceral contrast to the peaceful images of tiles and water which preceded. The transition from first to second sequence is violent and grating, implying a harsh reality outside invading the secure internal space. But the bathroom’s tranquillity could also be seen as static and cold, while in the second part a sense of birth and vitality is communicated, suggesting productivity as the artist appears to be tearing herself out of a womb. Neither of the two parts is privileged over the other, indicating that Hatoum is expressing difference rather than making a didactic political statement, drawing the viewer’s attention to the difficult co-existence of contrasting extremes within social structures on both microcosmic (individual and familial) and macrocosmic (political) levels.

“Variation on Discord and Divisions” (1984) is a disturbing performance where the artist, wearing an opaque mask and all dressed in black, crawls between the rows of spectators to reach the performance space. She then performs a number of actions that culminate with her removing raw kidneys from under her clothes, cutting them up, putting them on plates, and serving them one by one to the audience. Without referencing any specific conflict, Hatoum addresses notions of exile, war and oppression. Dressed in black with a covered face, the artist presents herself to the audience as an anonymous body, and as such takes various forms through the different actions of the performance. Hatoum’s “Road Works” performance first took place in 1985 in Brixton, London, after a series of race riots. The protests had been spurred on by the then Prime Minister – Margaret Thatcher’s newly-introduced police enforced stop-and-search laws that unfairly targeted the low-income Afro-Caribbean communities living in the area. During her performance, Hatoum walked barefoot through the streets for an hour, dragging behind Doc Marten boots, which she had attached to her ankles by their laces. These boots were in fact the footwear worn at the time by both the Metropolitan Police and by the gangs of skinheads also involved in the riots, therefore representing both parties. Having completed the performance, Hatoum’s ankles were sore from the heavy weight of the shoes, and her feet scuffed and scratched from the unforgiving concrete. What were once the light-stepping feet of a Surrealist flâneur (Hatoum, in the same way as a man who saunters around observing society, often walks the streets of London looking for inspiration) are here transformed into heavy-laden dragging boots – a sort of ball and chain. The artist therefore subverts traditional patriarchal art movements and shows us what happens when a woman decides to investigate the world. During her performance, passers-by in the street made various observations – interestingly, some made comments about an “invisible man” and asked if “she knew she was being followed”. In an interview with John Tusa on the BBC Hatoum explained that such moments of audience participation brought humor to the performance, and as such made the otherwise difficult and painful experience easier to bear. “Measures of Distance” (1988) collates cross-country phone calls between Hatoum and her mother. It is an uncharacteristically autobiographical work for Hatoum and one that she was inspired to make not long after her forced exile to London. The film speaks of her feelings of displacement, disorientation, and of the loss and separation from her family. Throughout the piece she overlays still footage of her mother in the shower with Arabic script taken from letters passed between mother and daughter, which Hatoum then reads aloud in both Arabic and English, the voices can be muffled and difficult to hear and the imagery can be difficult to see because of the text. The script is devised from six years of correspondence and speaks of how difficult it is to be apart, how her family is managing in war-torn Lebanon, as well as other various anecdotes shared between a mother and daughter catching up on lost time.

Photo: Mona Hatoum, Roadworks, 1985. Documentation of performance, Brixton, London. Color video with sound; 6 minutes, 45 seconds. © Mona Hatoum. Photo: Stefan Rohner, courtesy Kunstmuseum St. Gallen

Info: Curator: Bana Kattan, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 220 E Chicago Ave., Chicago IL, USA, Duration: 29/3-26/11/2023, Days & Hours: Tue 10:00-21:00, Wed0Sun 10:00-17:00, https://mcachicago.org/