TRACES: Anselm Kiefer

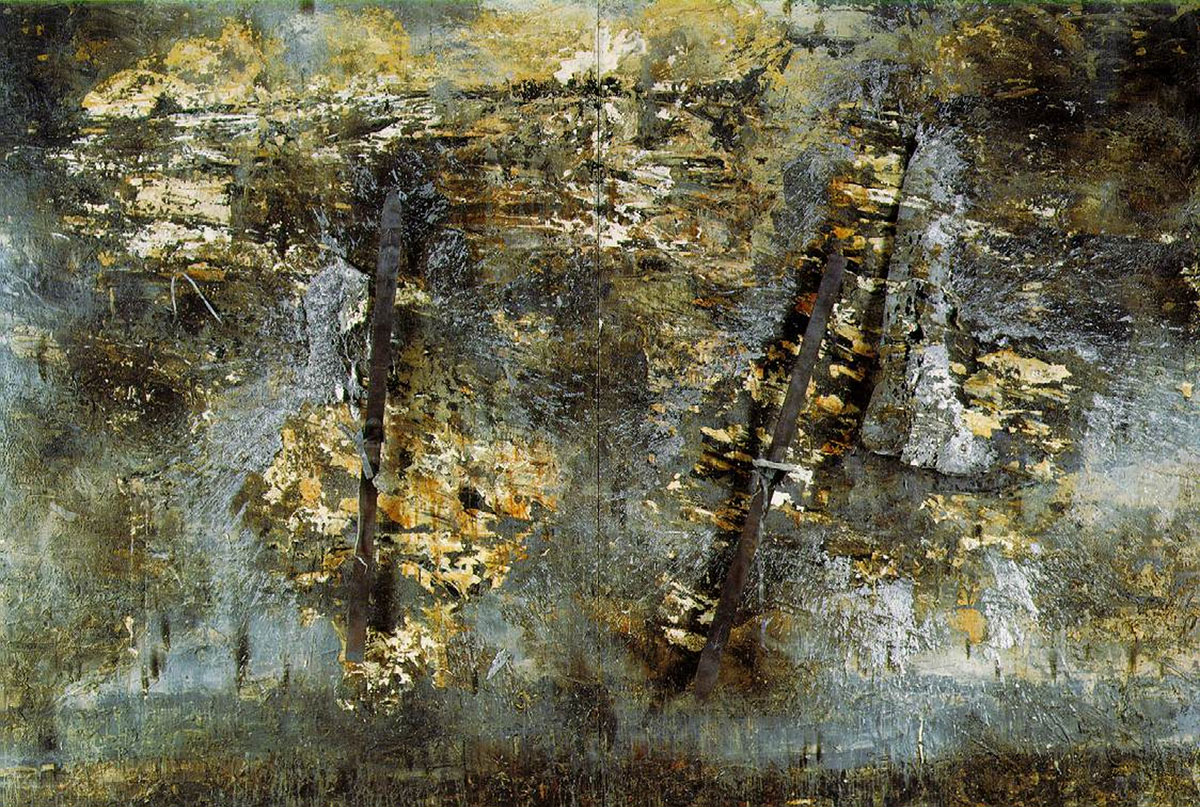

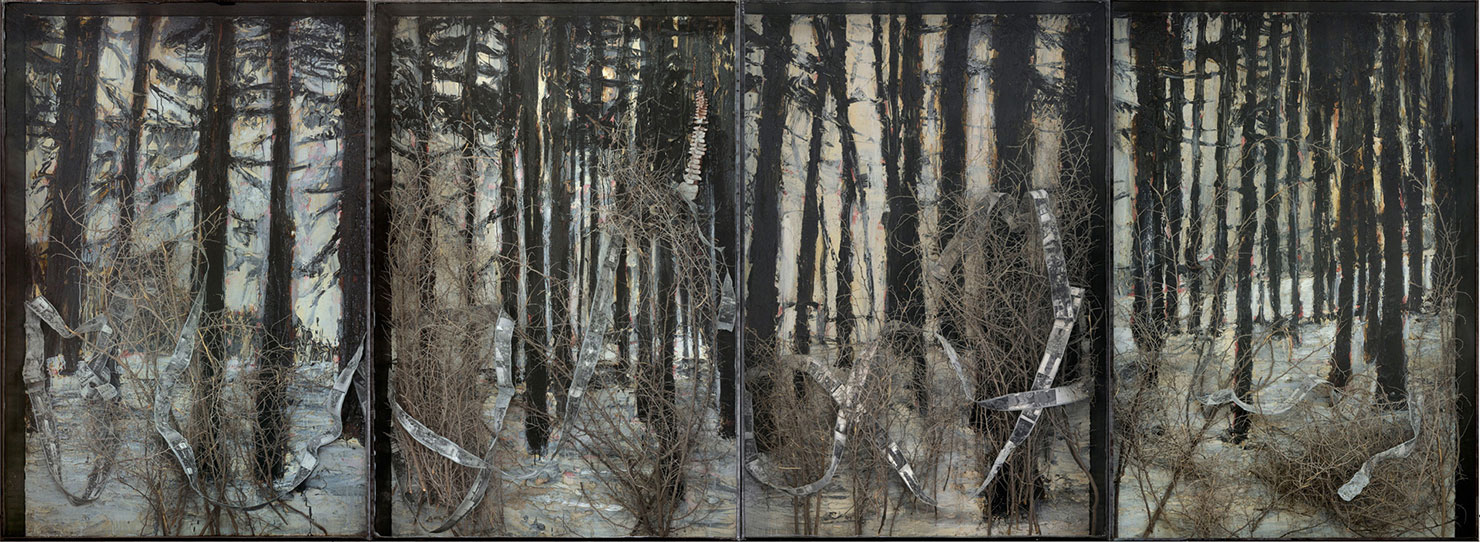

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Anselm Kiefer (8/3/1945- ), one of the most influential artists to come out of postwar Germany. His monumental, often confrontational canvases were groundbreaking at a time when painting was considered all but dead as a medium. The artist is most known for his subject matter dealing with German history and myth, particularly as it relates to the Holocaust. These works forced his contemporaries to deal with Germany’s past in an era when acknowledgment of Nazism was taboo. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Anselm Kiefer (8/3/1945- ), one of the most influential artists to come out of postwar Germany. His monumental, often confrontational canvases were groundbreaking at a time when painting was considered all but dead as a medium. The artist is most known for his subject matter dealing with German history and myth, particularly as it relates to the Holocaust. These works forced his contemporaries to deal with Germany’s past in an era when acknowledgment of Nazism was taboo. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

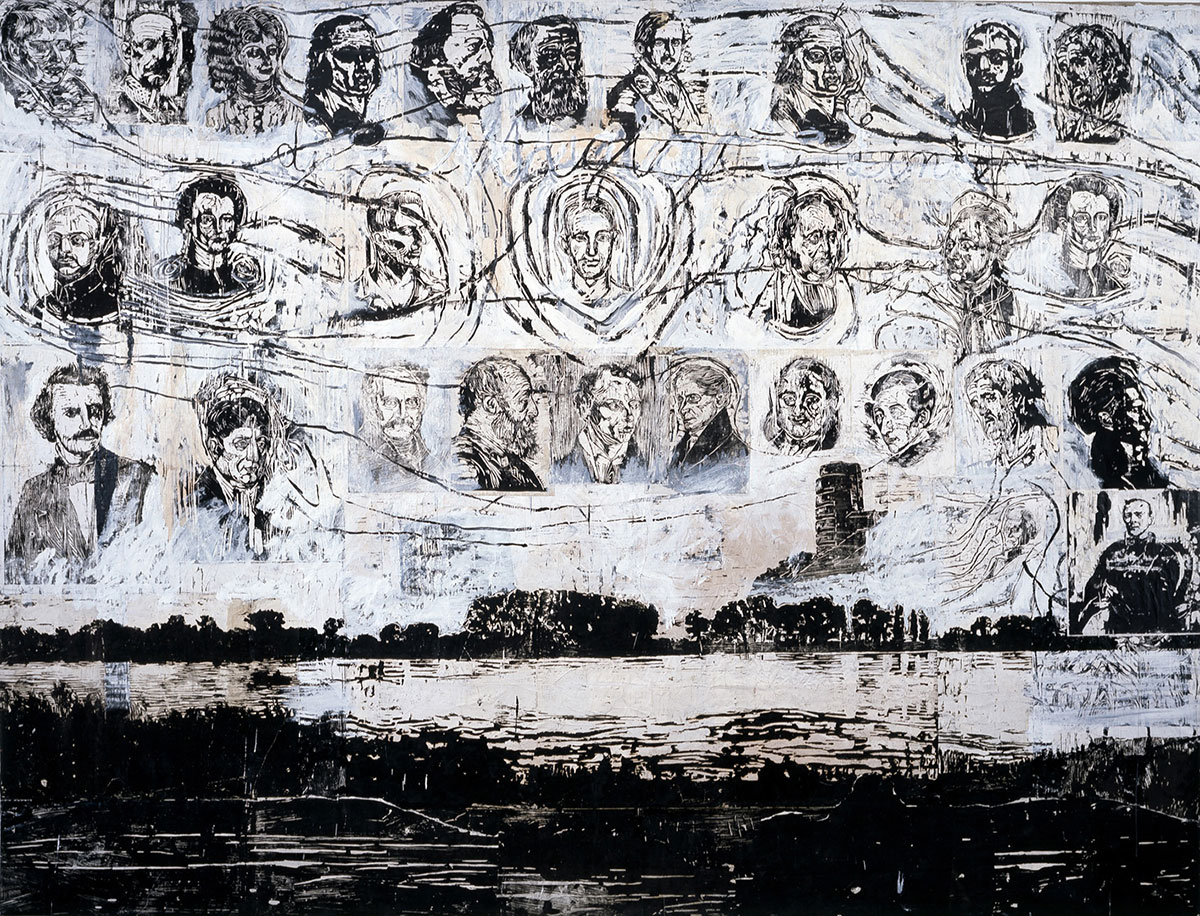

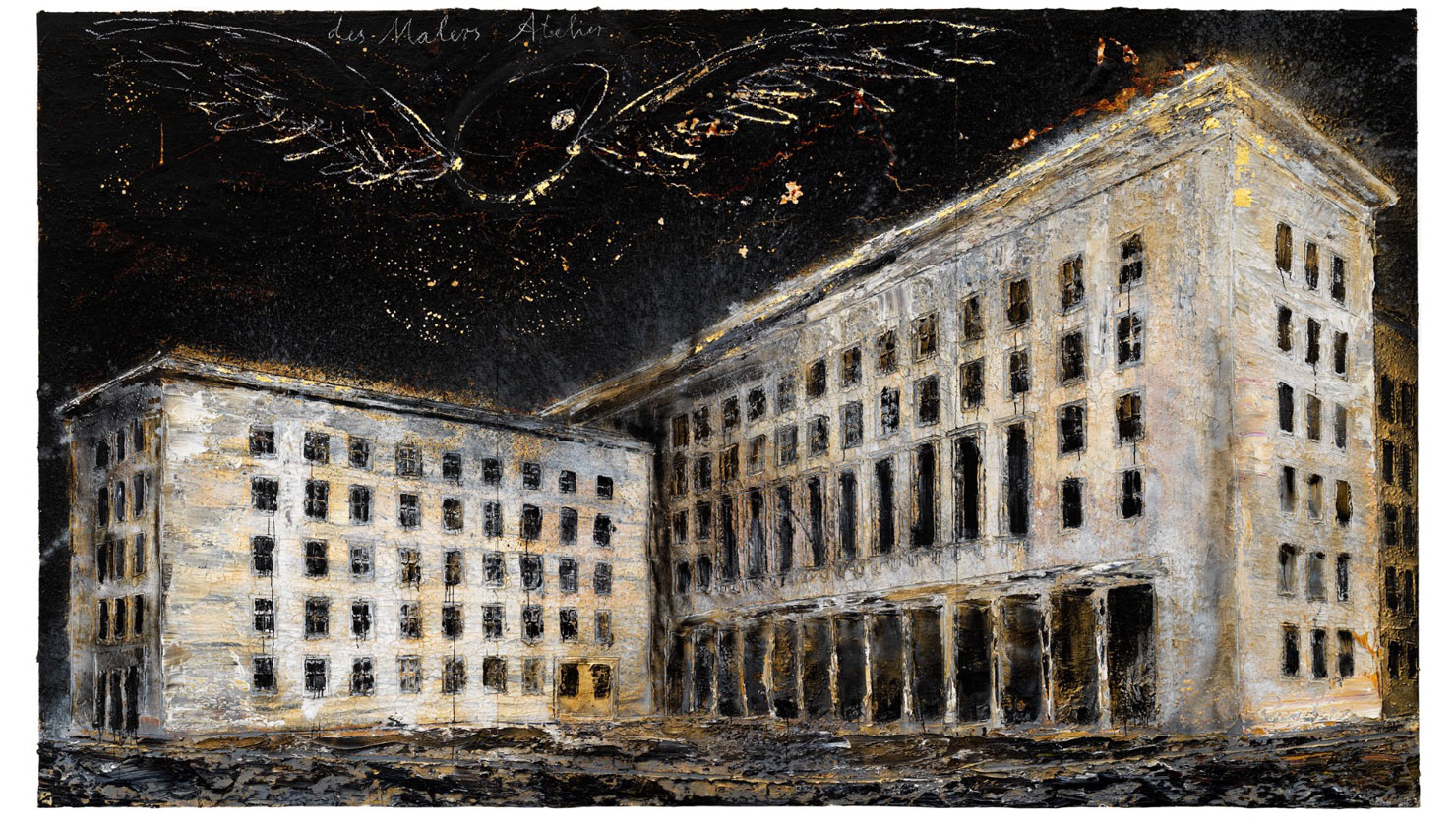

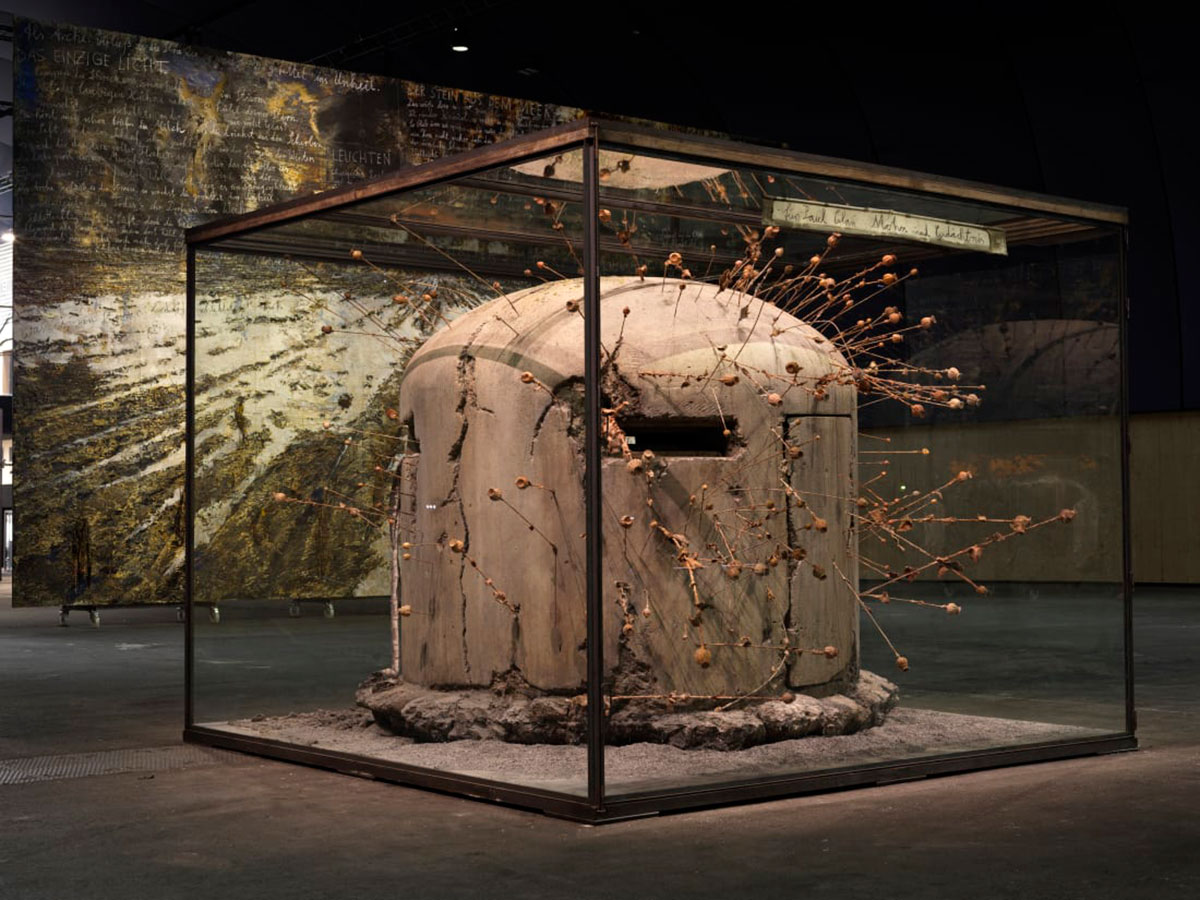

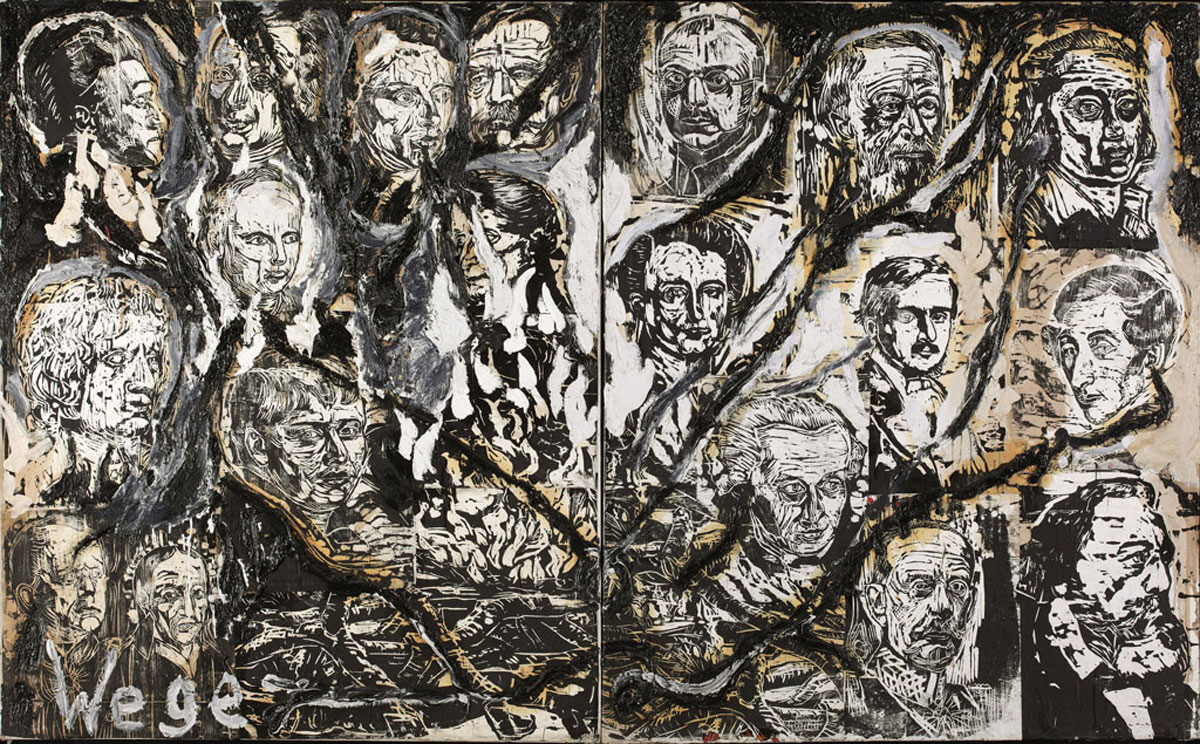

Anselm Kiefer was born on March 8, 1945 during the final months of World War II. The son of an art teacher, Kiefer was drawn to art and saw himself as an artist. He was raised in a Catholic home in the Black Forest near the eastern bank of the Rhine, an environment that would play a formative role in his development as an artist and would provide imagery and symbolism for his work. His family moved to Ottersdorf in 1951 and Kiefer attended grammar school in Rastatt. Although he had artistic ambitions from an early age, Kiefer studied law and Romance languages between 1965 and 1966 at the Albert-Universitat, Freiberg. Soon thereafter he abandoned his aspiration to become a lawyer to focus solely on visual art, taking classes with the influential painter Peter Dreher at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildende Kunste in Karlsruhe. During this period, at the age of 24, he also traveled extensively throughout Europe. Kiefer was part of a generation of Germans who felt the shame and guilt of the Holocaust, but had no personal experience of it. The artist has stated that the lack of discussion of WWII in school became a creative wellspring for him. He began his artistic career with a provocative photographic series titled Occupations (1969), which caused controversy because of its overt dealing with the Nazi past. In 1970 Kiefer moved to Düsseldorf where he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie and befriended Joseph Beuys, who would have an enduring influence on Kiefer, as a mentor and informal teacher. Impressed by Kiefer’s use of irony in reference to Germany’s past, Beuys saw great potential in the young artist and urged him to explore painting. Kiefer switched from photography to other media as a result, and in 1971 he created his first large landscape paintings. Drawing largely from Beuys’s conceptual approach and use of symbols, Kiefer began to develop his own unique representational language, focusing on evocative landscapes and interiors. He continued to explore themes of German history, culture, and mythology, depicting the country’s rural pastures, while engaging with the legacies of Germany’s artistic past, including the composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner and the Romantic landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich. Appearing at first glance to be simple bucolic landscapes, these works are imbued with Germany’s morbid past, evoking the desolate fields of mass burial sites and concentration camps. Beuys would remain a lasting influence on his work, but Kiefer also befriended fellow Neo-Expressionist painter Georg Baselitz, who would become his first patron and an artistic collaborator during this period. Baselitz purchased several works by Kiefer in 1974, allowing the artist to continue his seminal early series despite their provocative subject matter. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Kiefer traveled outside of Germany, with several trips in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East. These experiences greatly influenced his perspective and his work, motivating a shift away from themes of German history toward subjects more broadly related to the roles of art and mythology in social and religious contexts. Impacted by the cultural upheavals in Israel in particular, he integrated motifs of Jewish mysticism and the teachings of the Kabbalah into his paintings. Similarly inspired by a visit to Egypt, Kiefer appropriated the rich visual vocabulary of religious idolatry and hieroglyphic symbols from the nation’s vast trove of ancient art and artifacts. While this period saw the use of new motifs, including sigils, and a fascination with spiritual and occult symbolism, it was also characterized by Kiefer’s use of a number of new materials. In his 1981 series “Margarete and Shulamite”, for example, the artist used, for the first time, straw in his work, which he preferred for its tangible, malleable, and ephemeral qualities. While he had previously explored the use of glass, natural materials like straw, flowers, and ash would come to be central fixtures in his work. Lead, which he had used in previous works also became more dominant in this period after he bought the lead roof of a Cologne cathedral when the roof was being redone in the 1980s. As Neo-Expressionism rose to prominence during the late 1970s and 1980s, Kiefer quickly gained worldwide fame, and in 1980 he was chosen to represent Germany at the Venice Biennale along with Baselitz. This decision, made by the Stadelsche Kunstinstitut Director Klaus Gallwitz, validated Neo-Expressionism as a movement and forced the country to come to terms with German history in an international context. The presentation also served to catapult Kiefer’s career into the global art arena, leading to widespread recognition. In 1992 Kiefer left his first wife of approximately 20 years and their three children, moving from a small town outside of Frankfurt to a new 200-acre studio complex in Barjac, France, which had been an abandoned silk factory. Over time Kiefer transformed the space into a Gesamtkunstwerk that included towers, tunnels, and buildings. Between 1995 and 2001 he moved beyond his traditional subject matter, undertaking an abstract series based on the cosmos and broadening his repertoire of themes and media. At the same time, he renewed his long-standing interest in sculpture and text, creating a compelling series based on the Russian Futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov and revisiting the work of the Romanian poet Paul Celan, whose writings recur throughout Kiefer’s oeuvre. In 2008 he left the Barjac complex in the hands of a caretaker with plans to let nature take its course and moved to Paris with his second wife, the Austrian photographer Renate Graf, and their two children. His studio in Paris is large as well: 36,000 square meters in a former Samaritaine department store warehouse at Croissy-Beaubourg.

Anselm Kiefer was born on March 8, 1945 during the final months of World War II. The son of an art teacher, Kiefer was drawn to art and saw himself as an artist. He was raised in a Catholic home in the Black Forest near the eastern bank of the Rhine, an environment that would play a formative role in his development as an artist and would provide imagery and symbolism for his work. His family moved to Ottersdorf in 1951 and Kiefer attended grammar school in Rastatt. Although he had artistic ambitions from an early age, Kiefer studied law and Romance languages between 1965 and 1966 at the Albert-Universitat, Freiberg. Soon thereafter he abandoned his aspiration to become a lawyer to focus solely on visual art, taking classes with the influential painter Peter Dreher at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildende Kunste in Karlsruhe. During this period, at the age of 24, he also traveled extensively throughout Europe. Kiefer was part of a generation of Germans who felt the shame and guilt of the Holocaust, but had no personal experience of it. The artist has stated that the lack of discussion of WWII in school became a creative wellspring for him. He began his artistic career with a provocative photographic series titled Occupations (1969), which caused controversy because of its overt dealing with the Nazi past. In 1970 Kiefer moved to Düsseldorf where he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie and befriended Joseph Beuys, who would have an enduring influence on Kiefer, as a mentor and informal teacher. Impressed by Kiefer’s use of irony in reference to Germany’s past, Beuys saw great potential in the young artist and urged him to explore painting. Kiefer switched from photography to other media as a result, and in 1971 he created his first large landscape paintings. Drawing largely from Beuys’s conceptual approach and use of symbols, Kiefer began to develop his own unique representational language, focusing on evocative landscapes and interiors. He continued to explore themes of German history, culture, and mythology, depicting the country’s rural pastures, while engaging with the legacies of Germany’s artistic past, including the composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner and the Romantic landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich. Appearing at first glance to be simple bucolic landscapes, these works are imbued with Germany’s morbid past, evoking the desolate fields of mass burial sites and concentration camps. Beuys would remain a lasting influence on his work, but Kiefer also befriended fellow Neo-Expressionist painter Georg Baselitz, who would become his first patron and an artistic collaborator during this period. Baselitz purchased several works by Kiefer in 1974, allowing the artist to continue his seminal early series despite their provocative subject matter. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Kiefer traveled outside of Germany, with several trips in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East. These experiences greatly influenced his perspective and his work, motivating a shift away from themes of German history toward subjects more broadly related to the roles of art and mythology in social and religious contexts. Impacted by the cultural upheavals in Israel in particular, he integrated motifs of Jewish mysticism and the teachings of the Kabbalah into his paintings. Similarly inspired by a visit to Egypt, Kiefer appropriated the rich visual vocabulary of religious idolatry and hieroglyphic symbols from the nation’s vast trove of ancient art and artifacts. While this period saw the use of new motifs, including sigils, and a fascination with spiritual and occult symbolism, it was also characterized by Kiefer’s use of a number of new materials. In his 1981 series “Margarete and Shulamite”, for example, the artist used, for the first time, straw in his work, which he preferred for its tangible, malleable, and ephemeral qualities. While he had previously explored the use of glass, natural materials like straw, flowers, and ash would come to be central fixtures in his work. Lead, which he had used in previous works also became more dominant in this period after he bought the lead roof of a Cologne cathedral when the roof was being redone in the 1980s. As Neo-Expressionism rose to prominence during the late 1970s and 1980s, Kiefer quickly gained worldwide fame, and in 1980 he was chosen to represent Germany at the Venice Biennale along with Baselitz. This decision, made by the Stadelsche Kunstinstitut Director Klaus Gallwitz, validated Neo-Expressionism as a movement and forced the country to come to terms with German history in an international context. The presentation also served to catapult Kiefer’s career into the global art arena, leading to widespread recognition. In 1992 Kiefer left his first wife of approximately 20 years and their three children, moving from a small town outside of Frankfurt to a new 200-acre studio complex in Barjac, France, which had been an abandoned silk factory. Over time Kiefer transformed the space into a Gesamtkunstwerk that included towers, tunnels, and buildings. Between 1995 and 2001 he moved beyond his traditional subject matter, undertaking an abstract series based on the cosmos and broadening his repertoire of themes and media. At the same time, he renewed his long-standing interest in sculpture and text, creating a compelling series based on the Russian Futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov and revisiting the work of the Romanian poet Paul Celan, whose writings recur throughout Kiefer’s oeuvre. In 2008 he left the Barjac complex in the hands of a caretaker with plans to let nature take its course and moved to Paris with his second wife, the Austrian photographer Renate Graf, and their two children. His studio in Paris is large as well: 36,000 square meters in a former Samaritaine department store warehouse at Croissy-Beaubourg.