TRACES: Katharina Fritsch

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Katharina Fritsch (14/2/1956- ), who is celebrated as one of the most innovative sculptors of our time, she mines the history, myths, and fairy tales of Germany as well as her own thoughts and dreams to explore the nature of human perception and experience. She draws her subjects from everyday life and alters them through unexpected shifts in scale and color, creating objects that blur the boundaries between the ordinary and the deeply symbolic. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Katharina Fritsch (14/2/1956- ), who is celebrated as one of the most innovative sculptors of our time, she mines the history, myths, and fairy tales of Germany as well as her own thoughts and dreams to explore the nature of human perception and experience. She draws her subjects from everyday life and alters them through unexpected shifts in scale and color, creating objects that blur the boundaries between the ordinary and the deeply symbolic. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

By Efi Michalarou

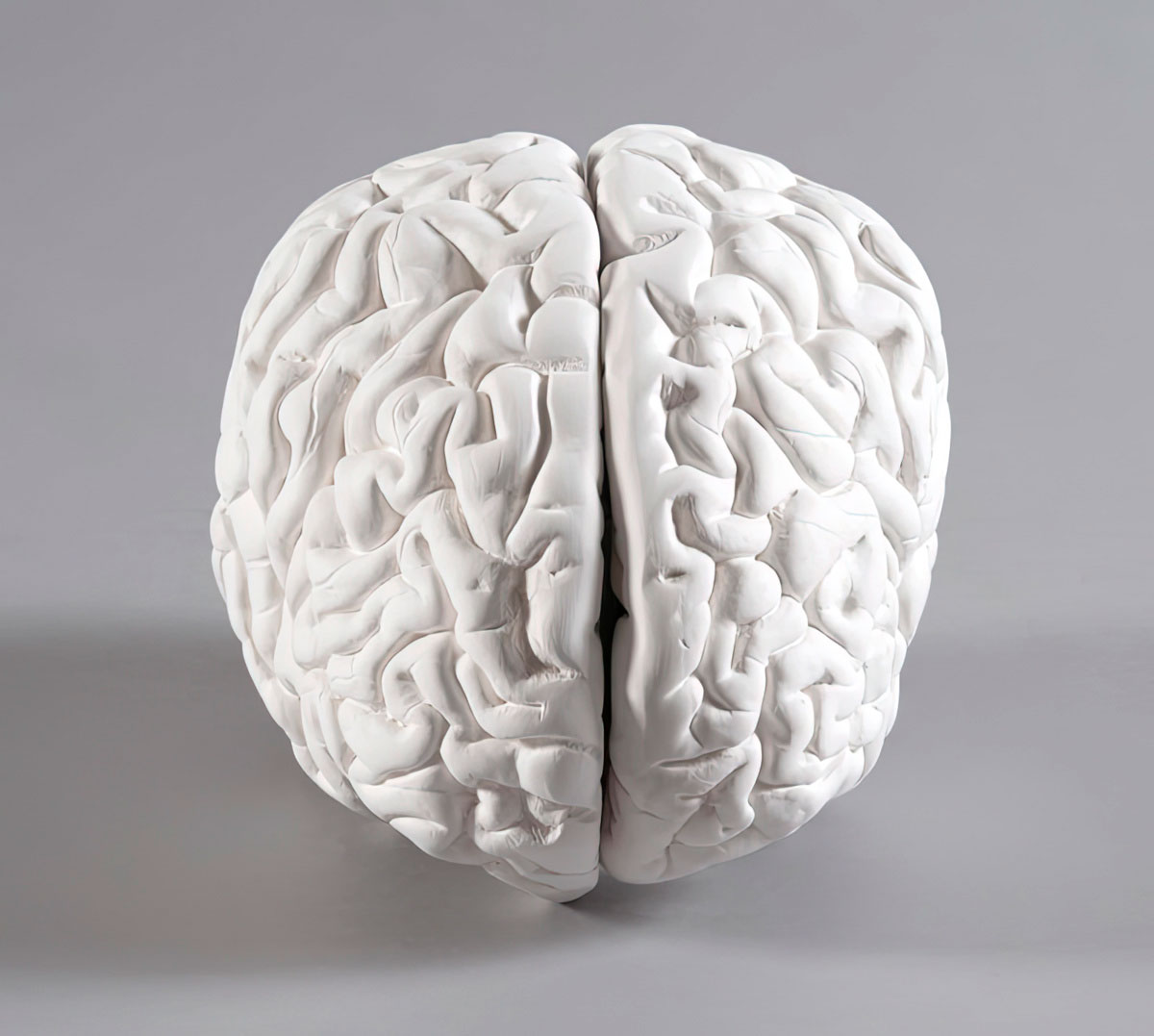

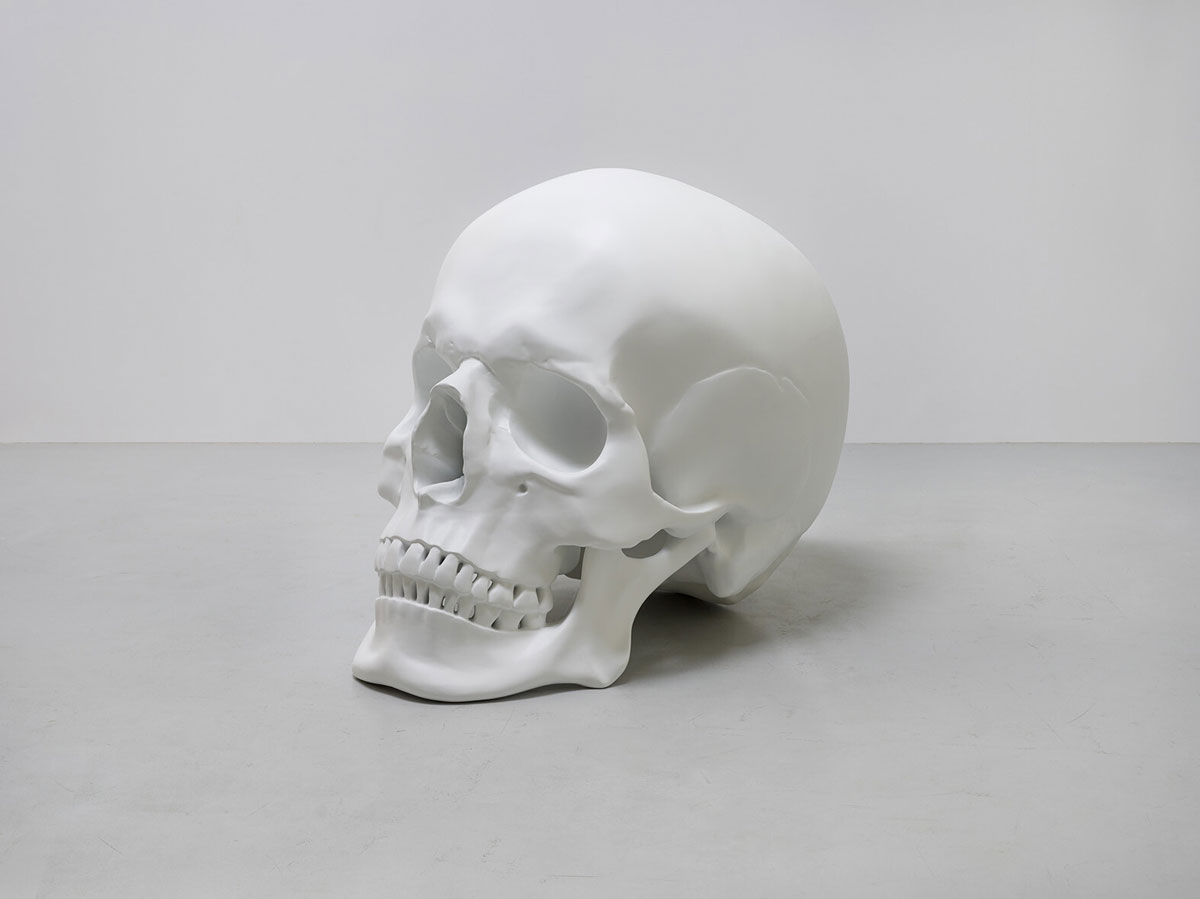

Born in Essen, West Germany, Katharina Fritsch studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy from 1977 to 1981. Although she was admitted to the program as a painter, she soon began exploring sculpture, making miniature versions of architectural structures and household objects familiar from her childhood. In 1982, she created “Madonnenfigur” (Madonna Figure), a multiple based on a figurine commemorating the miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France, in 1858. Cast by hand in plaster and painted a matte finish of garish, fluorescent yellow, Fritsch’s version becomes banal, even cartoonish. Because she designated it an unlimited edition, the number of copies that could exist is theoretically infinite, erasing the line between fine art and souvenir object. Five years later, Fritsch reimagined the work as a monument, creating a large-scale version for temporary display in a public square in Münster. The devotional object has been an ongoing interest for Fritsch, who has also made multiples based on statuettes of St. Catherine, St. Nicholas, and a pair of praying hands. And while she creates a wide variety of works – objects, images, sound works – she is especially known for her sculptures. All of her utilitarian objects – umbrellas, bottles – or symbolic objects – skulls, crosses, the tower of Pisa – are executed with incredible technical skill. The artist creates moulds from which the works are cast out of polyester, plaster, or aluminium. While these exact and precise shapes leave no doubt as to the nature of the objects, they nonetheless have a troubling effect, since scale is not necessarily respected, and the pieces are covered in a single solid colour that makes them seem unreal. For example, it could be a tongue-in-cheek rendering of a statuette of the Madonna like those found in Lourdes, but in fluorescent yellow, or the silhouette of a monk entirely covered in black. The artist thus recasts objects and characters that then lose their individuality and familiarity to become abstractions. From this emerges a sense of unease, these shapes acting on the mind like recollections. Taken from various sources (the everyday world, pop culture, art history, fairy tales), they belong to a collective memory, which is then more or less consciously rekindled in the spectator. One of her best-known creations, “Rattenkönig” (The Rat King, 1993), presents the nightmarish scene of a circle of giant rats whose tails are tied together, the origins of which can be traced back to Northern European fairy tales. “Tischgesellschaft” [Dinner, 1998] consists of a long rectangular table around which men are seated, all identical, which recalls both an image of the Last Supper from the history of art as a family dinner as seen by a child or a meeting taking place during an international convention. Fritsch often enlarges her multiples or combines them in groups to make large-scale installations with ambiguous narrative overtones. “Kind mit Pudeln” (Child with Poodles 1995–1996) comprises 128 examples of the multiple “Poodle”, arranged in dense circle around the figure of a naked infant. In “Mann und Maus” (Man and Mouse 1991–1992), a gigantic version of her multiple Mouse sits on the chest of a sleeping man. Are these animals guarding the vulnerable human beings or threatening them? As in many of Fritsch’s works, many answers are possible. “Hahn/Cock” (2013/2017) is one of Fritsch’s largest artworks to be housed in a public US museum collection. Towering nearly 25 feet over the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden in the north end of the park, the strutting blue rooster atop its artist-designed pedestal is at once lifelike and completely unreal. The rooster can be a symbol of pride, power, and courage or posturing and macho prowess. Fritsch has admitted that she enjoys “games with language,” and the sculpture’s tongue-in-cheek title knowingly plays on its double meaning. Blurring the boundaries between the ordinary and the deeply symbolic, “Hahn/Cock” presents an unexpected take on the idea of a traditional public monument. The artist often uses repeated patterns which, arranged geometrically inside a circle or grid, give the impression of psychotic proliferation. In 1995, she represented Germany along with Martin Honert and Thomas Ruff at the 46th Venice Biennale. In 1996 she was featured in a monographic exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, then in 2001 at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and the Tate Modern in London. In 2009 she was exhibited by the Kunsthaus Zurich, the Museum for Modern Art.

Born in Essen, West Germany, Katharina Fritsch studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy from 1977 to 1981. Although she was admitted to the program as a painter, she soon began exploring sculpture, making miniature versions of architectural structures and household objects familiar from her childhood. In 1982, she created “Madonnenfigur” (Madonna Figure), a multiple based on a figurine commemorating the miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary in Lourdes, France, in 1858. Cast by hand in plaster and painted a matte finish of garish, fluorescent yellow, Fritsch’s version becomes banal, even cartoonish. Because she designated it an unlimited edition, the number of copies that could exist is theoretically infinite, erasing the line between fine art and souvenir object. Five years later, Fritsch reimagined the work as a monument, creating a large-scale version for temporary display in a public square in Münster. The devotional object has been an ongoing interest for Fritsch, who has also made multiples based on statuettes of St. Catherine, St. Nicholas, and a pair of praying hands. And while she creates a wide variety of works – objects, images, sound works – she is especially known for her sculptures. All of her utilitarian objects – umbrellas, bottles – or symbolic objects – skulls, crosses, the tower of Pisa – are executed with incredible technical skill. The artist creates moulds from which the works are cast out of polyester, plaster, or aluminium. While these exact and precise shapes leave no doubt as to the nature of the objects, they nonetheless have a troubling effect, since scale is not necessarily respected, and the pieces are covered in a single solid colour that makes them seem unreal. For example, it could be a tongue-in-cheek rendering of a statuette of the Madonna like those found in Lourdes, but in fluorescent yellow, or the silhouette of a monk entirely covered in black. The artist thus recasts objects and characters that then lose their individuality and familiarity to become abstractions. From this emerges a sense of unease, these shapes acting on the mind like recollections. Taken from various sources (the everyday world, pop culture, art history, fairy tales), they belong to a collective memory, which is then more or less consciously rekindled in the spectator. One of her best-known creations, “Rattenkönig” (The Rat King, 1993), presents the nightmarish scene of a circle of giant rats whose tails are tied together, the origins of which can be traced back to Northern European fairy tales. “Tischgesellschaft” [Dinner, 1998] consists of a long rectangular table around which men are seated, all identical, which recalls both an image of the Last Supper from the history of art as a family dinner as seen by a child or a meeting taking place during an international convention. Fritsch often enlarges her multiples or combines them in groups to make large-scale installations with ambiguous narrative overtones. “Kind mit Pudeln” (Child with Poodles 1995–1996) comprises 128 examples of the multiple “Poodle”, arranged in dense circle around the figure of a naked infant. In “Mann und Maus” (Man and Mouse 1991–1992), a gigantic version of her multiple Mouse sits on the chest of a sleeping man. Are these animals guarding the vulnerable human beings or threatening them? As in many of Fritsch’s works, many answers are possible. “Hahn/Cock” (2013/2017) is one of Fritsch’s largest artworks to be housed in a public US museum collection. Towering nearly 25 feet over the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden in the north end of the park, the strutting blue rooster atop its artist-designed pedestal is at once lifelike and completely unreal. The rooster can be a symbol of pride, power, and courage or posturing and macho prowess. Fritsch has admitted that she enjoys “games with language,” and the sculpture’s tongue-in-cheek title knowingly plays on its double meaning. Blurring the boundaries between the ordinary and the deeply symbolic, “Hahn/Cock” presents an unexpected take on the idea of a traditional public monument. The artist often uses repeated patterns which, arranged geometrically inside a circle or grid, give the impression of psychotic proliferation. In 1995, she represented Germany along with Martin Honert and Thomas Ruff at the 46th Venice Biennale. In 1996 she was featured in a monographic exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, then in 2001 at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and the Tate Modern in London. In 2009 she was exhibited by the Kunsthaus Zurich, the Museum for Modern Art.