ART CITIES: Hong Kong-Imi Knoebel

Imi Knoebel’s resolutely abstract art investigates the fundamentals of painting and sculpture through an exploration of form, color and material. His aim is to uncover the basic material elements of art, which he locates in the simple interactions between humans and the essential conditions of our world. He remains true to the tradition of non-representational art, following in the footsteps of artists such as Kazimir Malevich or Piet Mondrian.

Imi Knoebel’s resolutely abstract art investigates the fundamentals of painting and sculpture through an exploration of form, color and material. His aim is to uncover the basic material elements of art, which he locates in the simple interactions between humans and the essential conditions of our world. He remains true to the tradition of non-representational art, following in the footsteps of artists such as Kazimir Malevich or Piet Mondrian.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: White Cube Gallery Archive

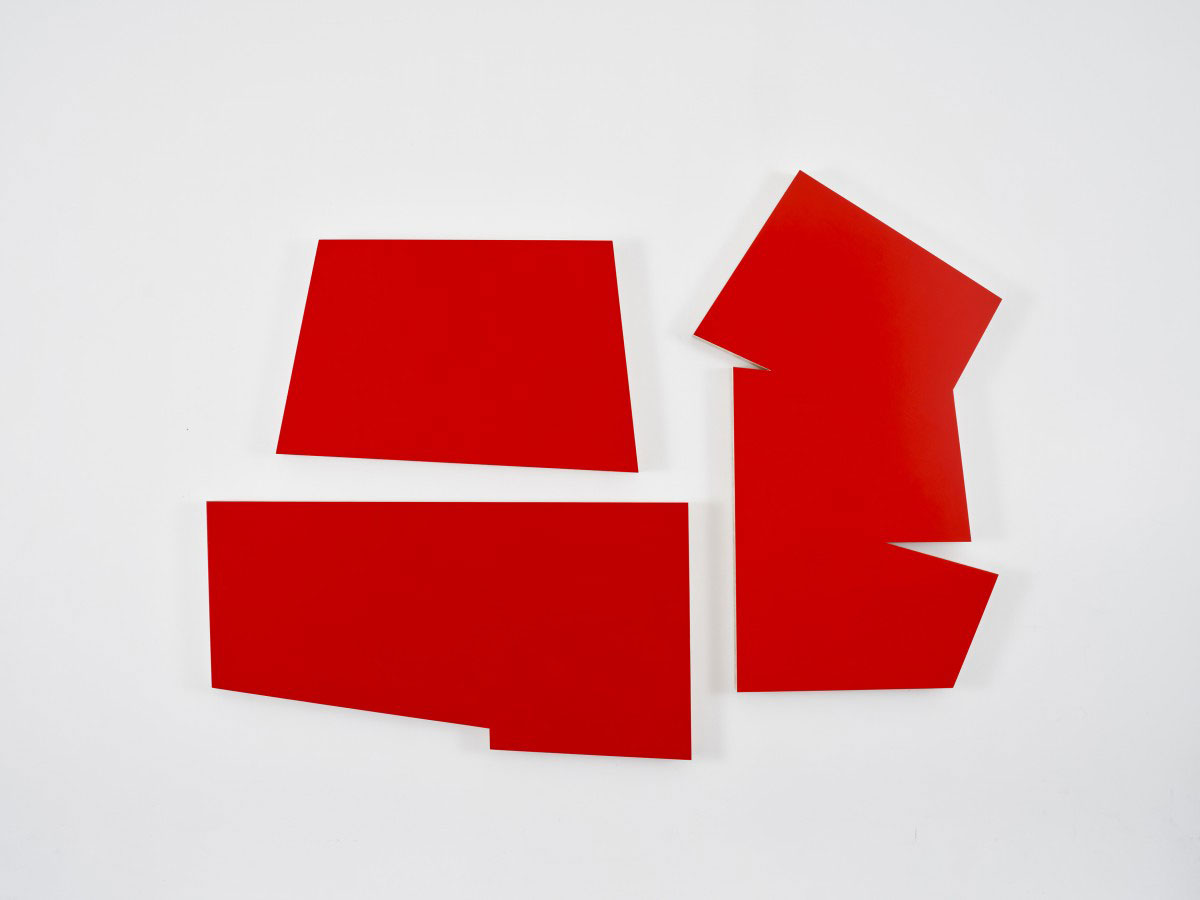

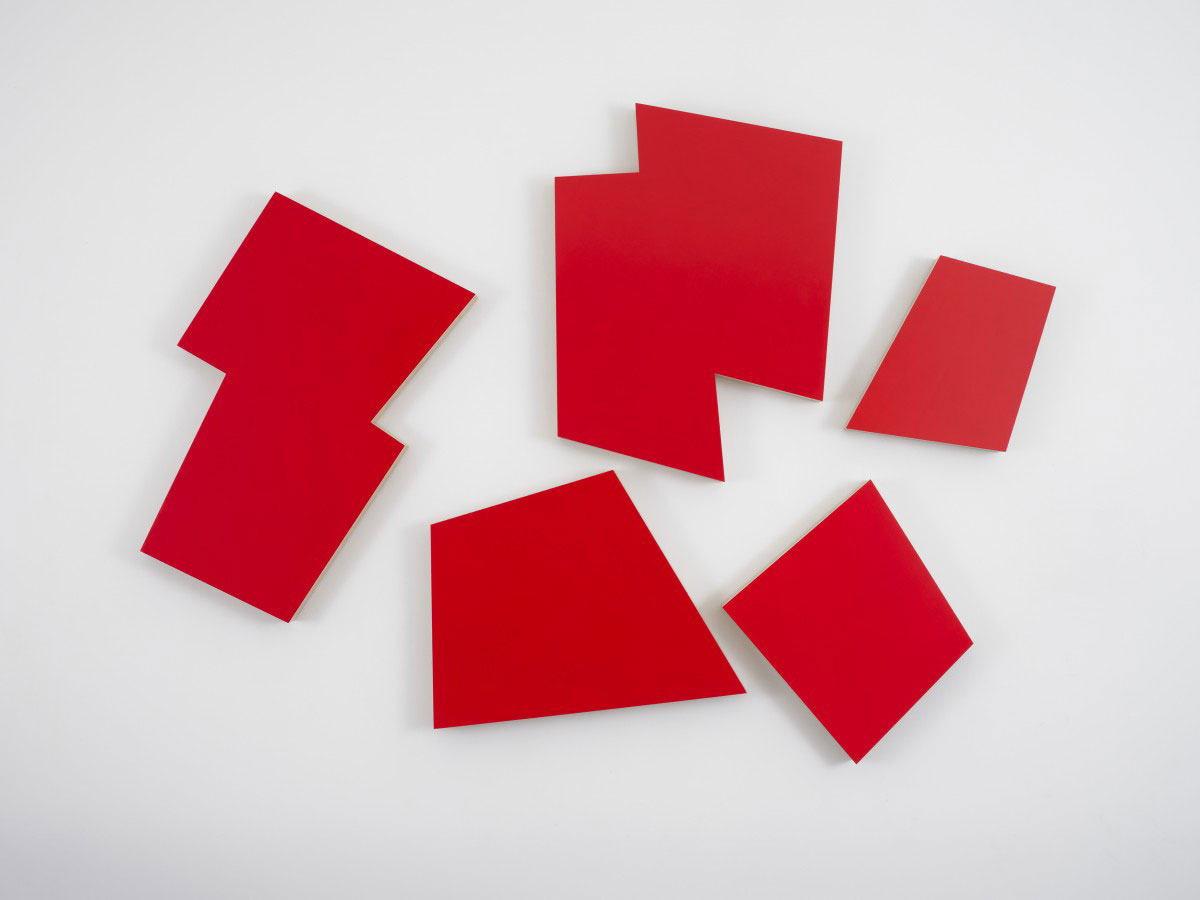

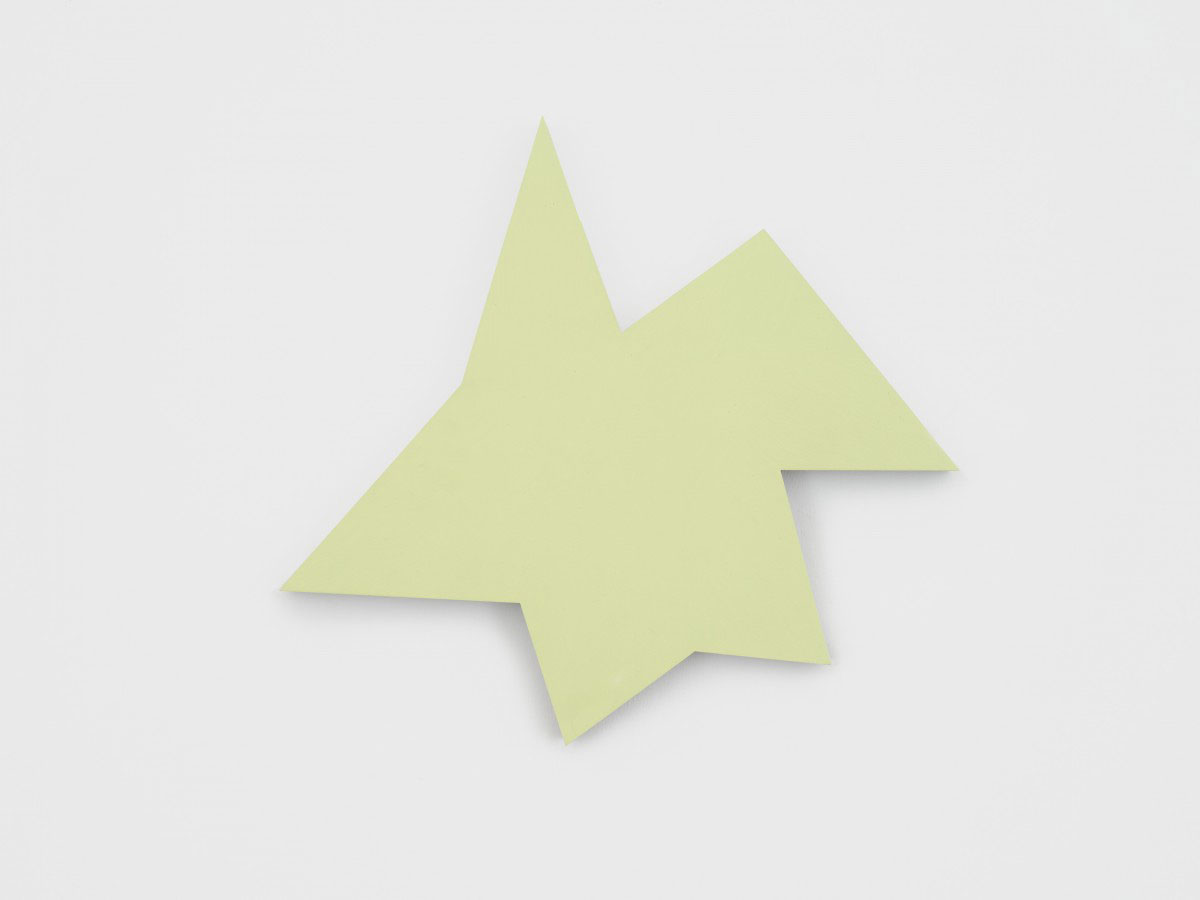

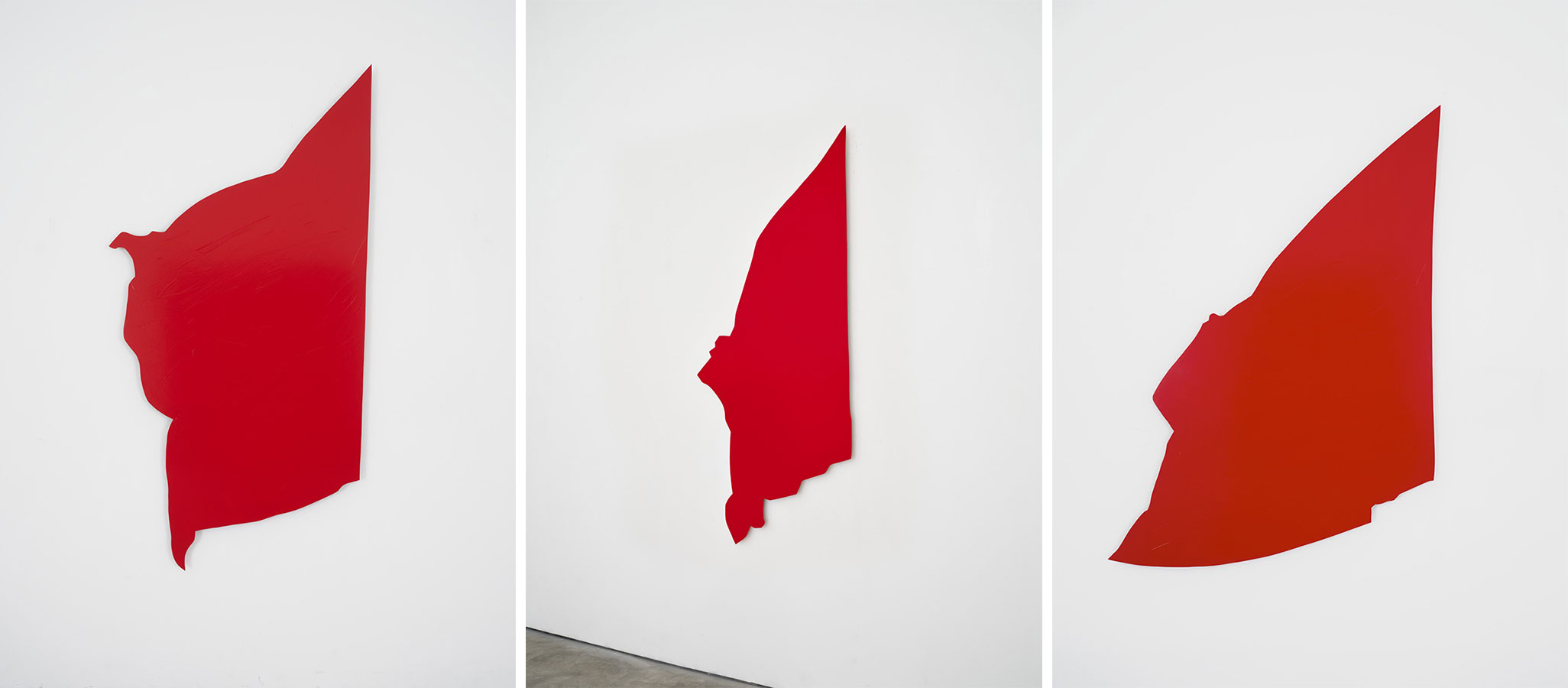

In “Green Flags”, Imi Knoebel presents two recent bodies of work in red acrylic paint on wood panels. Perhaps named for the afterimages they produce in the eye, the “Green Flags” series, which debuts in this exhibition, takes the form of silhouettes of flying flags. The multi-part “Konstellationen”, the titles of which reference astronomical bodies, are inspired by the shapes cast on the interiors and exteriors of buildings by the artist’s light projections of 1975, a fact referenced in each work’s dual dates. Additionally, examples of the artist’s “Kinderstern” multiples, in red and glow-in-the-dark phosphorescent paint are featured in the exhibition. Proceeds from sales of these “Children’s Star” works support a charity established by the artist and his wife Carmen that advocates for the human rights of children around the world. As a student, Imi Knoebel was inspired by Malevich’s theory of Suprematism, which rejected all representational imagery in favor of the “supremacy of pure artistic feeling”. When Knoebel joined Joseph Beuys’ class at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1964, the young artist began his career-long exploration of the expressive potential of art’s fundamental building blocks – line, form, colour and material. The artist cites his discovery of Malevich’s “Black Square” (1915) as a watershed moment that liberated his conception of painting, giving him ‘the overwhelming feeling that I could start at nothing’. He has developed an experimental approach and serial way of working, characterised by a haptic use of color, geometric vocabulary of forms and material simplicity. Imi Knoebel studied with Blinky Palermo (with whom he shared a studio), Jörg Immendorff, and Katharina Sieverding. In the wake of two world wars, decades of division, and multiple stages of collapse and renewal, these young artists necessarily aligned themselves to a history fraught with ideological conflict. Beuys was the center of this new artistic climate, retooling Germany’s romantic and lyrical past into politically and poetically charged objects, performances, and movements. Artists like Knoebel, however, felt that art should take a different path, and his work was not only different from but also often resistant to many of Beuys’s postulations and claims about the discipline. Countering romanticism, the central tradition of German art, Knoebel revives the purity of utopian modernism, using pared down forms of constructivism to take his painting to a zero point. He attempts expression without representation or the restrictions of ideological painting programs. The goal is to purify and cleanse the present from the past and to start again, relying on new materials and aesthetic forms to move forward. Painters who came of age in the postwar era dealt with a fresh cultural memory of the ascendency and fall of German nationalism, West Germany’s rapid economic recovery and expansion after the demise of fascism, and the division and subsequent union of East and West Germany during the communist era. Knoebel’s approach was to look for the basic roots of art, which he felt were not in rhetoric but in things, in the simple interaction between humans and the essential conditions of their world. When his friend and famous artist Blinky Palermo died in 1977, Imi Knoebel paid tribute to him by painting the “24 colours for Blinky” series. He then stopped using black and white and has been working extensively in color since. His canvases are at once gestural and formal, exploring the effects of material and color. The artist rejects any notion of spirituality. The “Latinists” series, 1987, clearly shows many of Knoebel’s concerns and interests. The forms, like those of American minimalism, are rudimentary (squares, rectangles, parallelograms) as are the materials of fiberboard, unused stretcher bars, and flat industrial white paint. Unlike American minimalism, however, Knoebel’s intention has nothing to do with finding a rational, positivist center by which to make art. Instead, his spare starting points become the criteria from which Knoebel’s intuitions take over, leading him to arrange his humble materials in ways that appeal to his aesthetic experiences and his perceptions of beautiful composition. The results are paintings that play into the realm of sculpture, retaining the basic figure/ground and picture plane conditions of a painting but extending off the wall and into the space, activating the room. Today, at 82, Knoebel creates an ever-evolving flow of nonobjective works. Ranging from geometric to freeform, from monochrome to multiple colors, they are inspired by his hands-on studio experiments rather than any overarching program.

Photo: Imi Knoebel, Kadmiumrot G G1–G3, 1975/2018, Acrylic on wood, Three parts, overall: 191 × 257 × 9 cm | 75 3/16 × 101 3/16 × 3 9/16 in., © Imi Knoebel, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Info: White Cube Gallery, 50 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong, Duration: 18/1-11/3/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-19:00, https://whitecube.com/

Center: Imi Knoebel, Green Flag 3, 2022, Acrylic on aluminium, 211.6 × 101.2 × 4.5 cm | 83 5/16 × 39 13/16 × 1 ¾ in., © Imi Knoebel, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Right: Imi Knoebel, Green Flag 1, 2022, Acrylic on aluminium, 213.8 × 112 × 4.5 cm | 84 3/16 × 44 1/8 × 1 3/4 in., © Imi Knoebel, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery