TRACES: Robert Longo

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist, filmmaker, photographer and musician, Robert Longo (7/1/1953- ). He worked with multiple mediums, including popular forms such as music videos and, later in his career, produced large-scale, detailed charcoal drawings of news images, such as those documenting racial strifes in the US as well as the migration crisis in Europe. This column is a tribute to very important artists, living or dead, who have left their trace in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist, filmmaker, photographer and musician, Robert Longo (7/1/1953- ). He worked with multiple mediums, including popular forms such as music videos and, later in his career, produced large-scale, detailed charcoal drawings of news images, such as those documenting racial strifes in the US as well as the migration crisis in Europe. This column is a tribute to very important artists, living or dead, who have left their trace in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

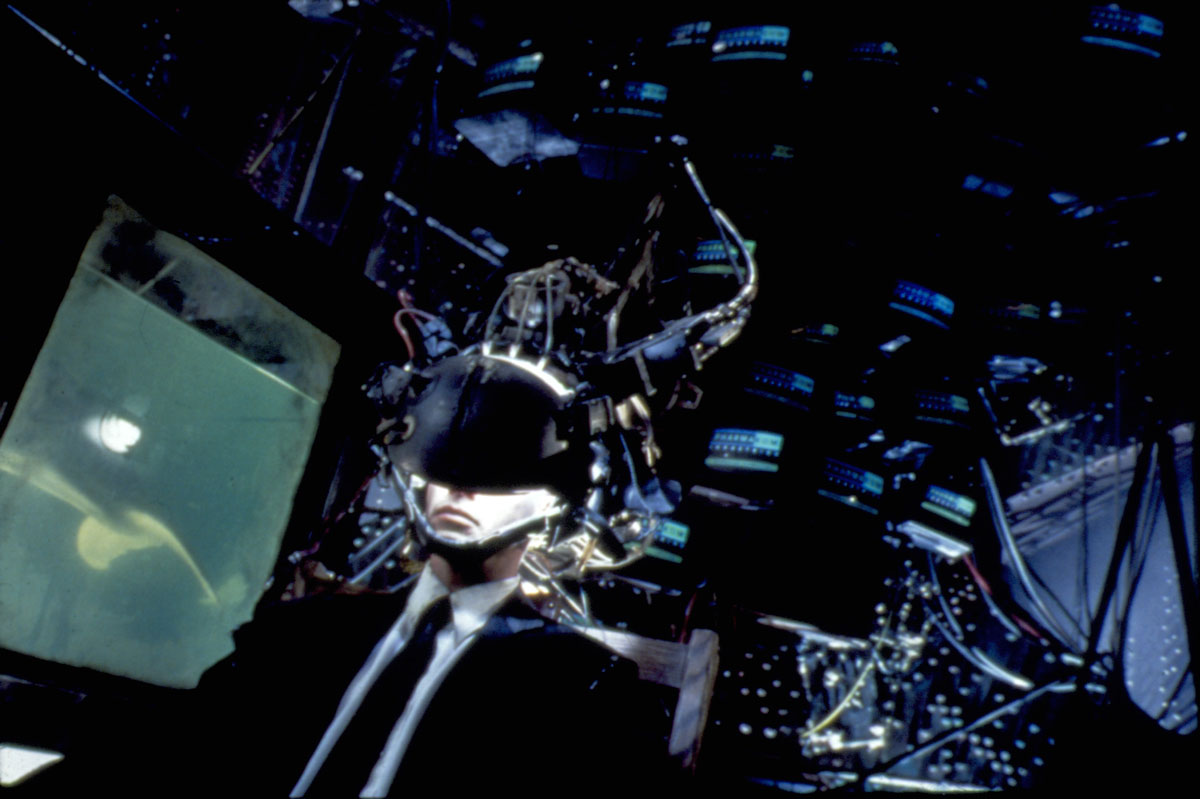

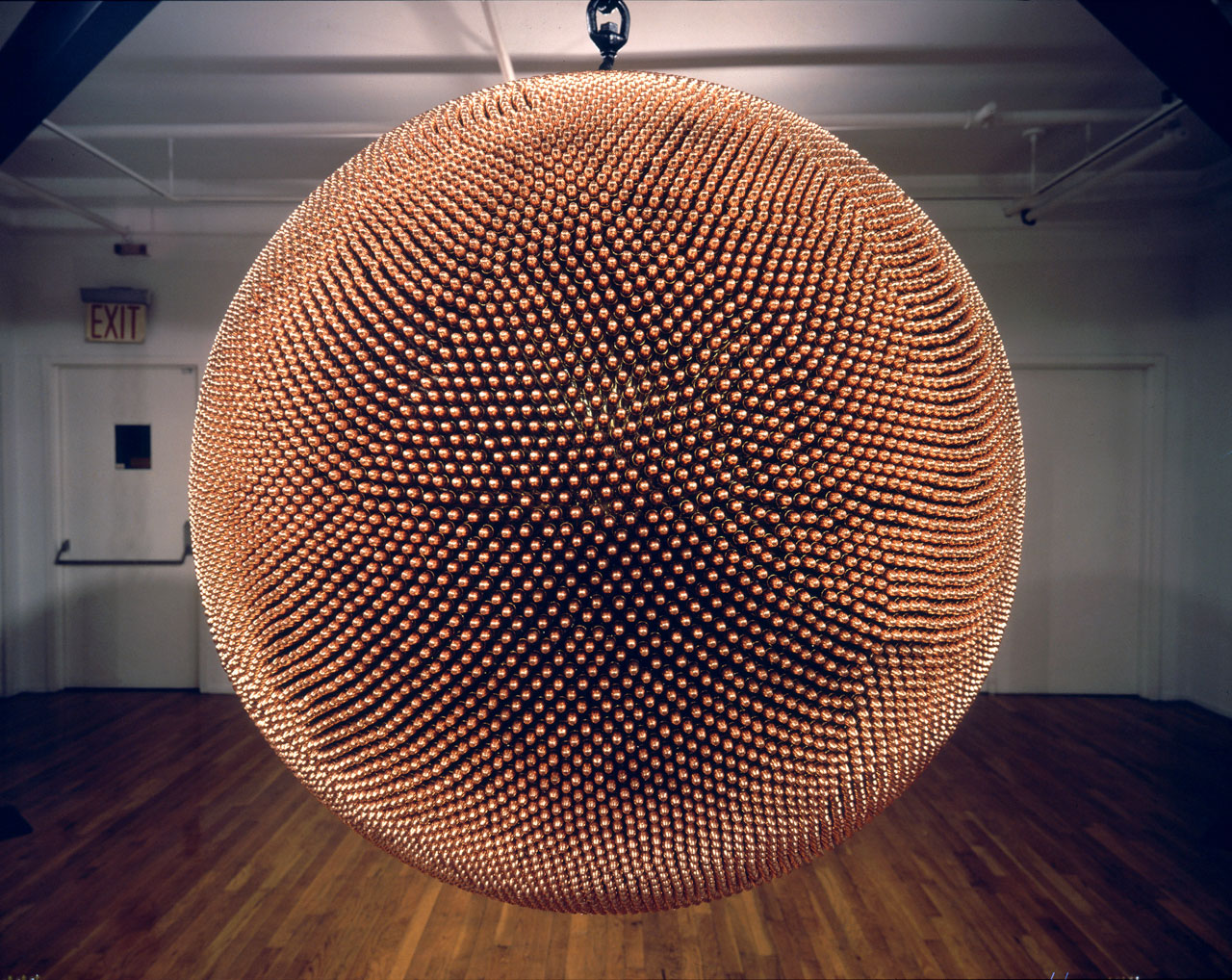

Born in Brooklyn, New York and raised on Long Island, Robert Longo’s early interest in mass media such as films and comic books had a profound influence on his later art. Dyslexia made school difficult for Longo, who described himself in his senior year of high school as the “hippy jock who was also organizing political protests”.Longo recalls that he “emerged as a conscious being during the Vietnam War,” with the 1970 Kent State University Massacre in Ohio solidifying his dedication to political causes. Longo enrolled in North Texas State University through college athletics. Needing to boost his academic performance, Longo, who knew he could draw, became an art major, although eventually he left without a degree. A grant in 1972 allowed him to study Art History and Restoration in Florence. Longo began to see himself in relation to the long trajectory of art history. Plotting his own educational tour of Europe’s museums, Longo realized that he wanted to create art. He studied art at State University College in Buffalo. Between 1973 and his graduation in 1975, he worked under the experimental filmmakers Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton, who introduced him to structural filmmaking and Sergei Eisenstein’s films, In 1974, along with his artist friends including Cindy Sherman, Longo co-founded the exhibition space Hallwalls. The forward-looking space saw exhibitions and talks by artists including Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Lynda Benglis, Robert Irwin, Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman, and Richard Serra. Through Hallwalls, Longo developed an important artistic network. He eventually moved, with Sherman, to New York in 1977 (the two dated from 1977-79 and then remained friends). Although he was trained in sculpture, Longo began to seriously approach drawing after his move to New York. After moving to New York, he worked as a studio assistant to Vito Acconci and Dennis Oppenheim. That same year, he was included in the seminal “Pictures” exhibition curated by Douglas Crimp at Artists Space. Regarded as one of the first exhibitions to pay attention to a new generation of artists shifting away from Minimalism and Conceptual Art, “Pictures” showcased artists who were all drawn toward image-making inspired by mass media. The artists included in the show became known, along with a number of others in their circles, as the “Pictures Generation”. The exhibition provided a seismic shift in Longo’s artistic career. Metro Pictures, the flagship gallery for the Generation from its founding in 1980, represented him, and over the course of the next decade, he became known as a preeminent member of the group, having achieved name recognition with his first solo show, which featured his 1981 “Men in the Cities” drawings. He began working with a multitude of media ranging from photography, drawing, sculpture, painting, film, and performance – all employed as critiques of capitalism, wars, and their ubiquity in the media, as well as the cult of history in the United States. In 1984, Longo premiered his wall-based “Combines” at Metro Pictures, the title a nod to Robert Rauschenberg’s work. An amalgam of painting, relief, and sculpture, Longo, in a 2014 interview, stated that these works “used Sergei Eisenstein’s theory of montage to juxtapose conflicting imagery and forms exploring the workings of reason, intuition, fantasy, and power; concepts that continue to be important [to his artistic practice]”. Concurrently, Longo became a key figure in New York’s underground art scene, collaborating with other arts-related groups and venues, rock bands, magazines, and filmmakers. Increasingly interested in film as a medium, he produced his first music videos in 1986 and a film the following year. Among his music videos, Longo was the director for the video for R.E.M’s “The One I Love,” the band’s breakthrough hit. In the video, Longo made use of imagery reminiscent of his “Men in the Cities” but, enabled by video as a medium, also played with layering moving images on top of each other, creating a shifting, sometimes disorienting visual tableau that goes with the song’s dark theme. Longo sees his music video work as part of his artistic trajectory. He describes it as an enjoyable way to develop and practice his film skills for application to longer movies. However, despite his work’s popularity and high demand, Longo began to clash with music executives as the industry became increasingly corporatized. Working across mediums, Longo’s art became associated with 1980s New York and its changing topography, from the wild adrenaline rush of Wall Street and subsequent gentrification to the storied nightlife and creative bounty of the city’s underground art and music scenes. His works consistently explored the role of images in pop culture, as well as the theme of disconnection and individual alienation in post-industrial society. Following Reagan’s economic policies and the first Gulf War, the 1990 recession marked another transition in his career. With the art market in turmoil, Longo moved to Paris, where he lived and worked before returning to the United States to direct “Johnny Mnemonic” (1994-95), a thriller starring Keanu Reeves, in Hollywood. The following year, Longo’s “Magellan” (1996), a series of 366 small-scale drawings taken from mass media over the course of a leap year, proved to be another aesthetic benchmark for his subsequent artworks. Comprising of subjects as varied as rock concerts, murder scenes, animals, superheroes, and plants, the series served as a catalogue of his thoughts and observations of the visual world. He drew them alone in his studio as an antidote to his filmmaking experience involving hundreds of people. The series together formed an “image lexicon” that he would draw on in his later works. For an artist whose artistic directions were often spurred by political events and climates, Longo describes the early 2000s, with “9/11” (2001) and the war in Iraq (2003) as having “profoundly affected.. [his] .. outlook on the world.” The scale of Longo’s charcoal works portraying scenes from current events became monumental. They gained their heft from his desire to impart a sense of weight to familiar news images, to render their presence impactful like a sculpture. In addition to these hyper-realistic charcoal drawings, he also experimented with digital printing, such as in “Essentials” (2009), which portrays images of what he calls “absolutes” – a mushroom cloud, a shark, a sleeping child, a rose, among others – that, to him, embodied the collective unconscious.

Born in Brooklyn, New York and raised on Long Island, Robert Longo’s early interest in mass media such as films and comic books had a profound influence on his later art. Dyslexia made school difficult for Longo, who described himself in his senior year of high school as the “hippy jock who was also organizing political protests”.Longo recalls that he “emerged as a conscious being during the Vietnam War,” with the 1970 Kent State University Massacre in Ohio solidifying his dedication to political causes. Longo enrolled in North Texas State University through college athletics. Needing to boost his academic performance, Longo, who knew he could draw, became an art major, although eventually he left without a degree. A grant in 1972 allowed him to study Art History and Restoration in Florence. Longo began to see himself in relation to the long trajectory of art history. Plotting his own educational tour of Europe’s museums, Longo realized that he wanted to create art. He studied art at State University College in Buffalo. Between 1973 and his graduation in 1975, he worked under the experimental filmmakers Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton, who introduced him to structural filmmaking and Sergei Eisenstein’s films, In 1974, along with his artist friends including Cindy Sherman, Longo co-founded the exhibition space Hallwalls. The forward-looking space saw exhibitions and talks by artists including Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Lynda Benglis, Robert Irwin, Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman, and Richard Serra. Through Hallwalls, Longo developed an important artistic network. He eventually moved, with Sherman, to New York in 1977 (the two dated from 1977-79 and then remained friends). Although he was trained in sculpture, Longo began to seriously approach drawing after his move to New York. After moving to New York, he worked as a studio assistant to Vito Acconci and Dennis Oppenheim. That same year, he was included in the seminal “Pictures” exhibition curated by Douglas Crimp at Artists Space. Regarded as one of the first exhibitions to pay attention to a new generation of artists shifting away from Minimalism and Conceptual Art, “Pictures” showcased artists who were all drawn toward image-making inspired by mass media. The artists included in the show became known, along with a number of others in their circles, as the “Pictures Generation”. The exhibition provided a seismic shift in Longo’s artistic career. Metro Pictures, the flagship gallery for the Generation from its founding in 1980, represented him, and over the course of the next decade, he became known as a preeminent member of the group, having achieved name recognition with his first solo show, which featured his 1981 “Men in the Cities” drawings. He began working with a multitude of media ranging from photography, drawing, sculpture, painting, film, and performance – all employed as critiques of capitalism, wars, and their ubiquity in the media, as well as the cult of history in the United States. In 1984, Longo premiered his wall-based “Combines” at Metro Pictures, the title a nod to Robert Rauschenberg’s work. An amalgam of painting, relief, and sculpture, Longo, in a 2014 interview, stated that these works “used Sergei Eisenstein’s theory of montage to juxtapose conflicting imagery and forms exploring the workings of reason, intuition, fantasy, and power; concepts that continue to be important [to his artistic practice]”. Concurrently, Longo became a key figure in New York’s underground art scene, collaborating with other arts-related groups and venues, rock bands, magazines, and filmmakers. Increasingly interested in film as a medium, he produced his first music videos in 1986 and a film the following year. Among his music videos, Longo was the director for the video for R.E.M’s “The One I Love,” the band’s breakthrough hit. In the video, Longo made use of imagery reminiscent of his “Men in the Cities” but, enabled by video as a medium, also played with layering moving images on top of each other, creating a shifting, sometimes disorienting visual tableau that goes with the song’s dark theme. Longo sees his music video work as part of his artistic trajectory. He describes it as an enjoyable way to develop and practice his film skills for application to longer movies. However, despite his work’s popularity and high demand, Longo began to clash with music executives as the industry became increasingly corporatized. Working across mediums, Longo’s art became associated with 1980s New York and its changing topography, from the wild adrenaline rush of Wall Street and subsequent gentrification to the storied nightlife and creative bounty of the city’s underground art and music scenes. His works consistently explored the role of images in pop culture, as well as the theme of disconnection and individual alienation in post-industrial society. Following Reagan’s economic policies and the first Gulf War, the 1990 recession marked another transition in his career. With the art market in turmoil, Longo moved to Paris, where he lived and worked before returning to the United States to direct “Johnny Mnemonic” (1994-95), a thriller starring Keanu Reeves, in Hollywood. The following year, Longo’s “Magellan” (1996), a series of 366 small-scale drawings taken from mass media over the course of a leap year, proved to be another aesthetic benchmark for his subsequent artworks. Comprising of subjects as varied as rock concerts, murder scenes, animals, superheroes, and plants, the series served as a catalogue of his thoughts and observations of the visual world. He drew them alone in his studio as an antidote to his filmmaking experience involving hundreds of people. The series together formed an “image lexicon” that he would draw on in his later works. For an artist whose artistic directions were often spurred by political events and climates, Longo describes the early 2000s, with “9/11” (2001) and the war in Iraq (2003) as having “profoundly affected.. [his] .. outlook on the world.” The scale of Longo’s charcoal works portraying scenes from current events became monumental. They gained their heft from his desire to impart a sense of weight to familiar news images, to render their presence impactful like a sculpture. In addition to these hyper-realistic charcoal drawings, he also experimented with digital printing, such as in “Essentials” (2009), which portrays images of what he calls “absolutes” – a mushroom cloud, a shark, a sleeping child, a rose, among others – that, to him, embodied the collective unconscious.