PRESENTATION: Yayoi Kusama-1945 to Now, Part II

Yayoi Kusama emerged as a global cultural icon for the twenty-first century by pursuing her uncompromising avant-garde vision. Over the past seven decades, she honed a singular personal aesthetic and core philosophy of life. Kusama’s work captivates millions by offering glimpses of boundless space and reflections on natural cycles of regeneration. Her artistic position is characterized by revolutionary interventions driven by the desire for an immersive union of body and artwork, and an urge to redefine the role of women in art (Part II).

Yayoi Kusama emerged as a global cultural icon for the twenty-first century by pursuing her uncompromising avant-garde vision. Over the past seven decades, she honed a singular personal aesthetic and core philosophy of life. Kusama’s work captivates millions by offering glimpses of boundless space and reflections on natural cycles of regeneration. Her artistic position is characterized by revolutionary interventions driven by the desire for an immersive union of body and artwork, and an urge to redefine the role of women in art (Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: M+ Museum Archive

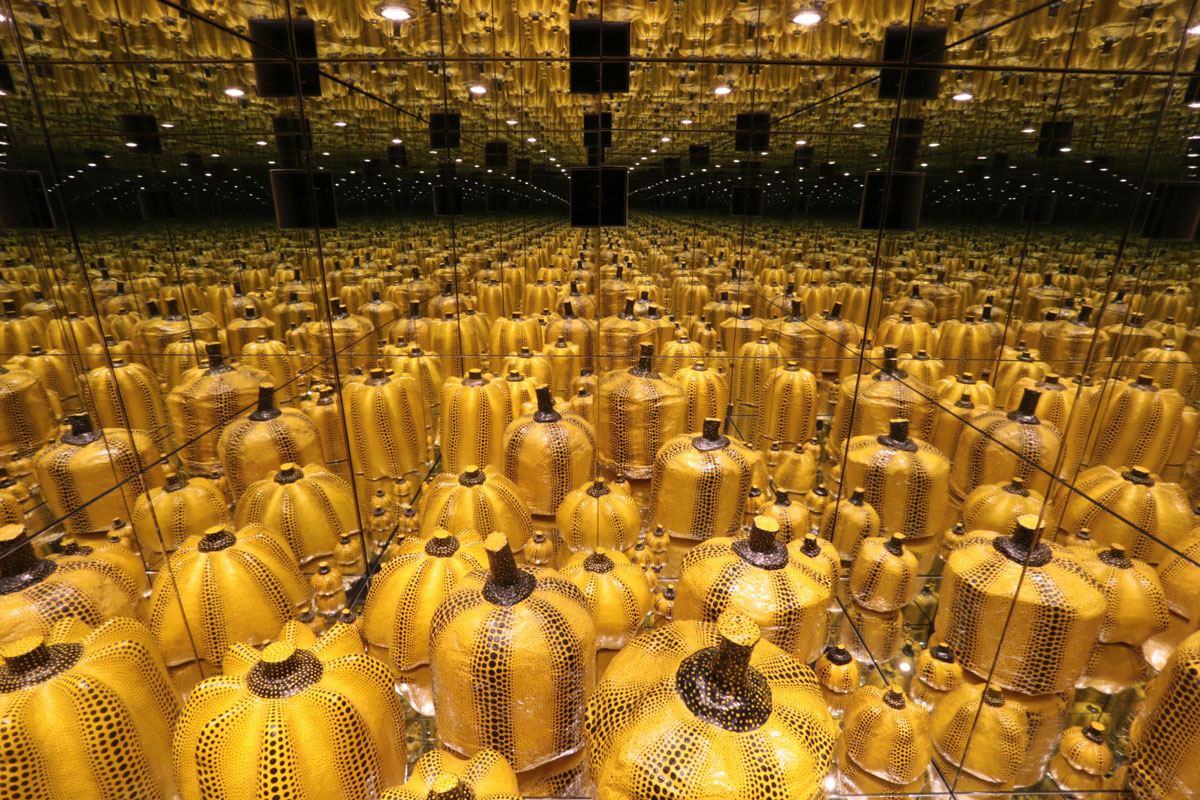

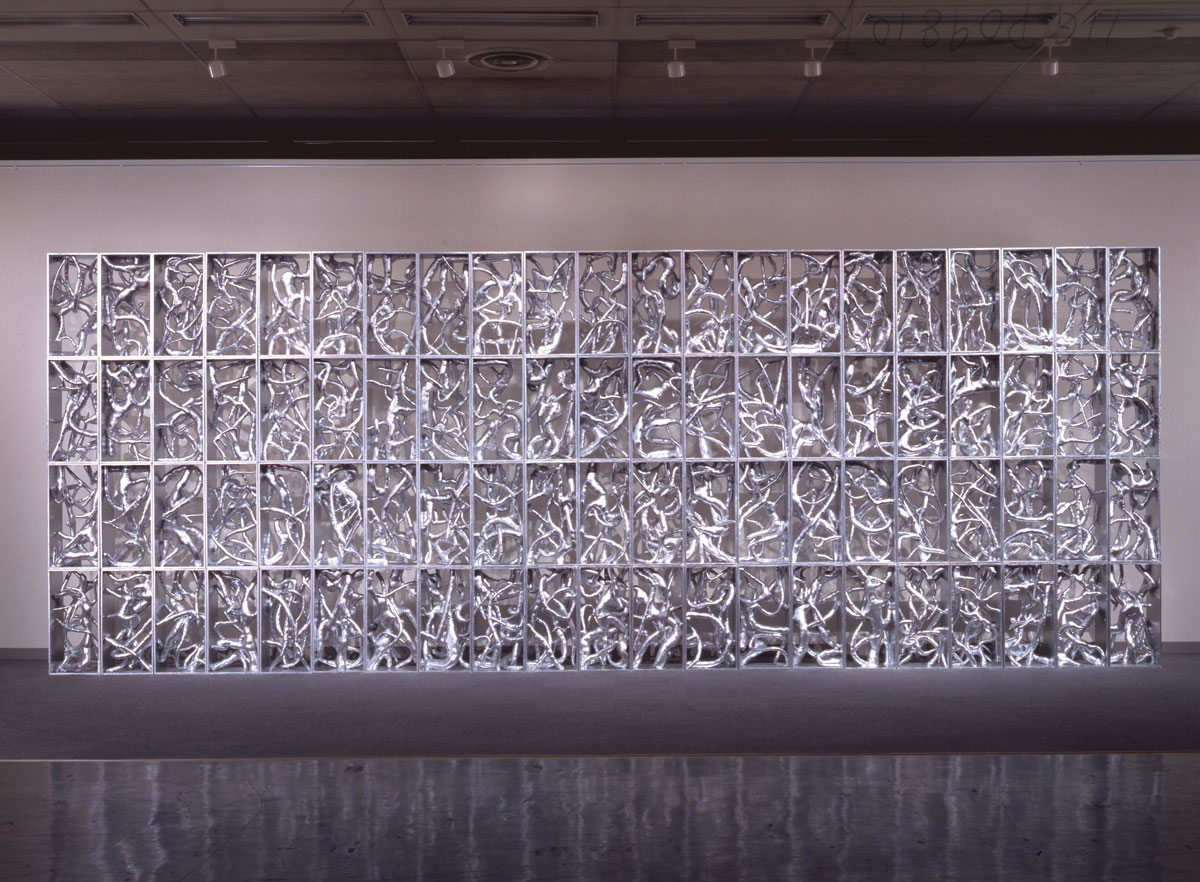

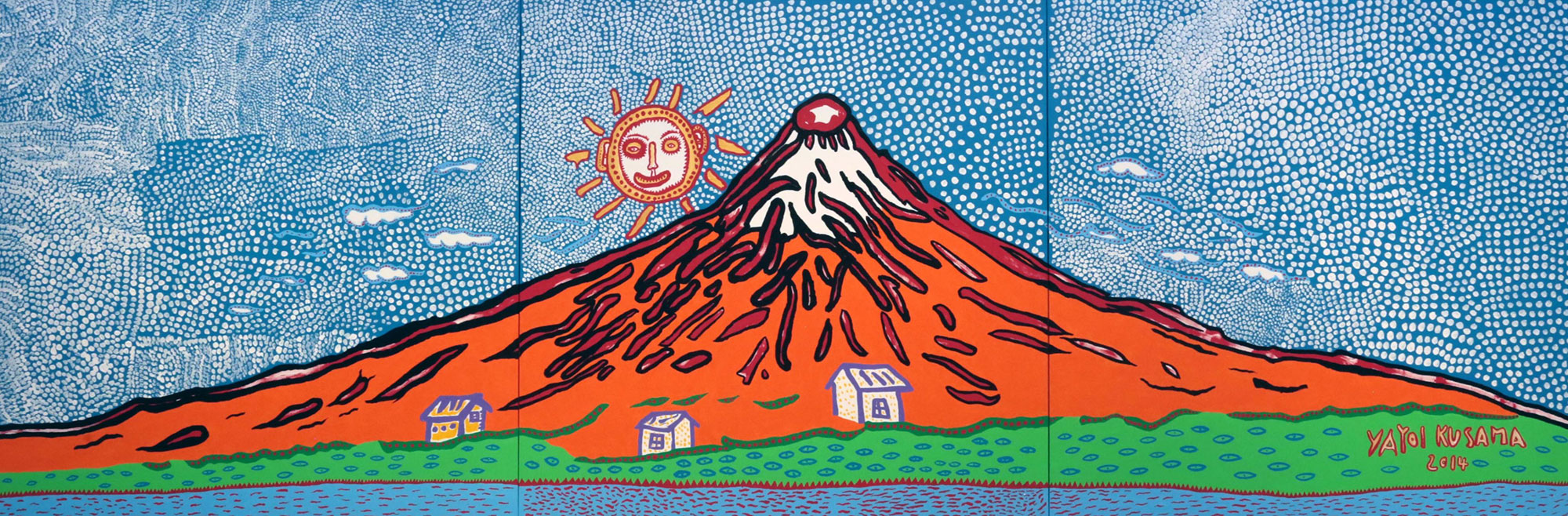

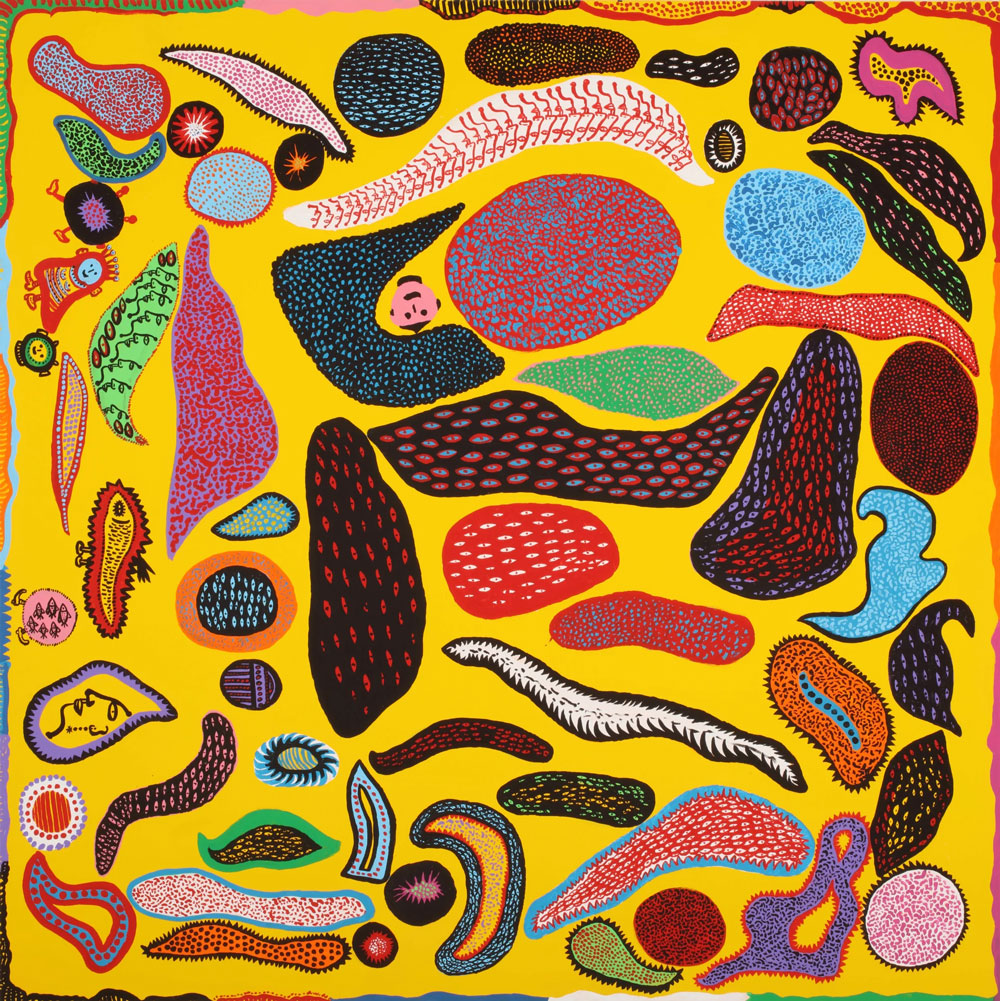

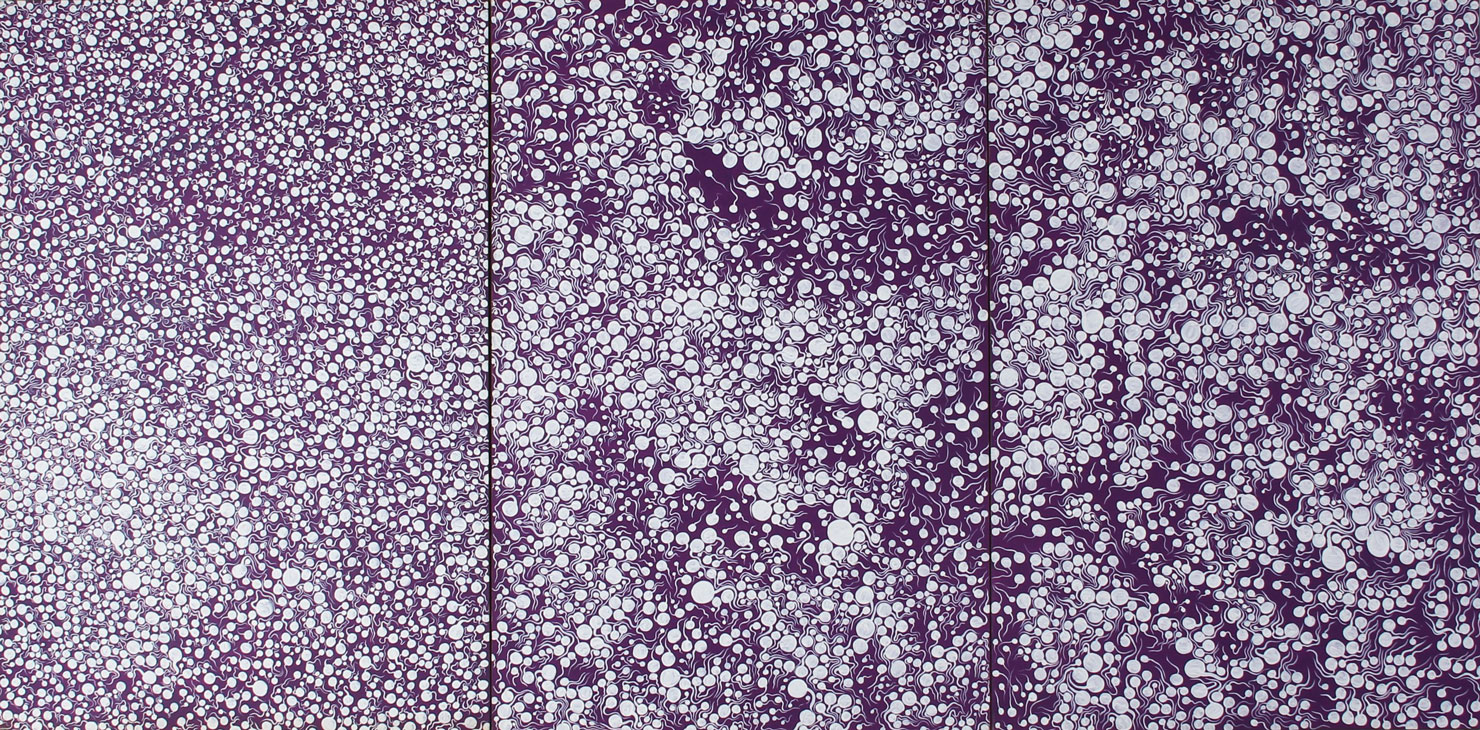

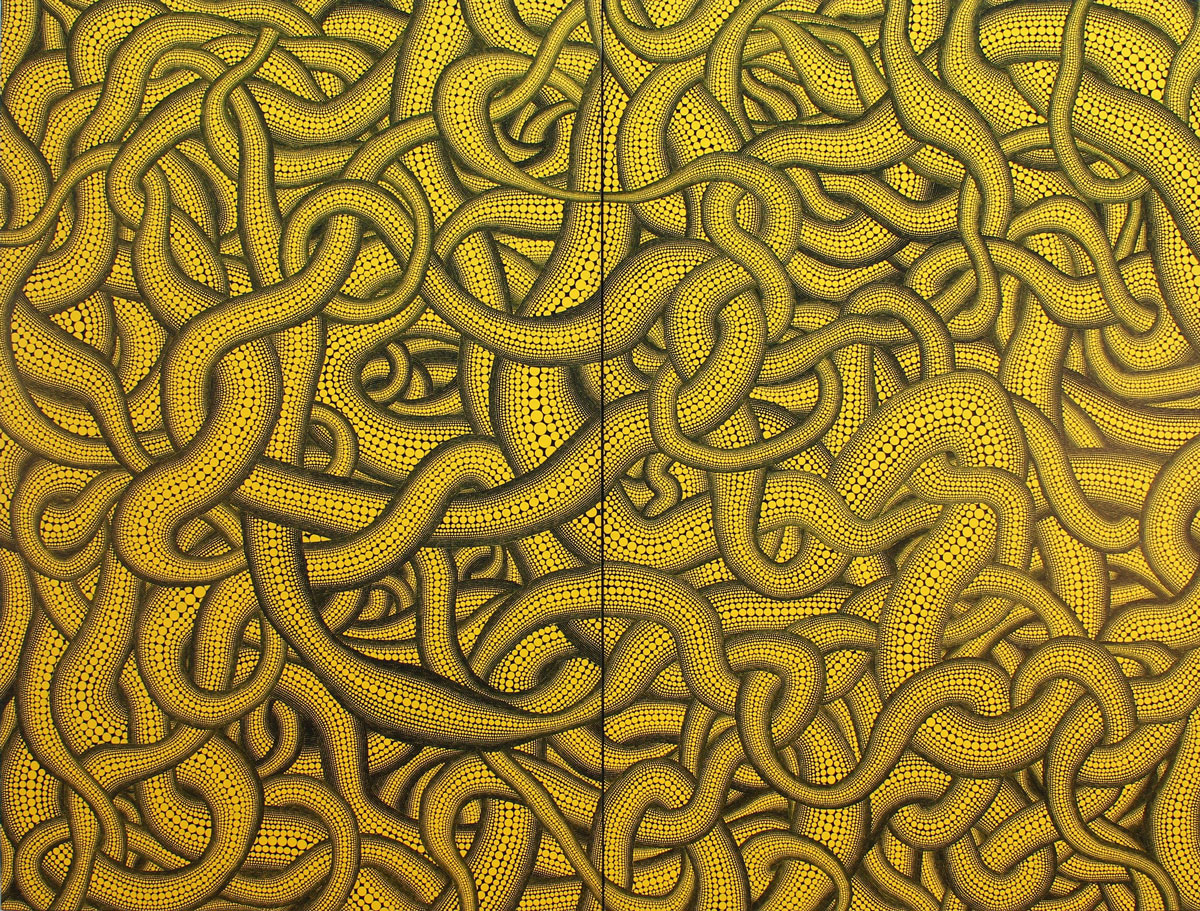

The exhibition “Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now” is the largest retrospective of the artist in Asia outside Japan. Featuring more than 200 works, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, installations, and archival material, this exhibition surveys Kusama’s career from the earliest drawings she made as a teenager during World War II to her most recent immersive art pieces. Organised chronologically and thematically, the retrospective guides visitors through Kusama’s career-long creative pouring divided into major themes: “Infinity”, “Accumulation”, “Radical Connectivity”, “Biocosmic”, “Death”, and “Force of Life”. In addition to tracing the origins of her practice, the exhibtion presents three brand-new works to bring audiences together. “Death of Nerves” (2022) is a colourful large-scale installation commissioned the Museum that provides a mesmerising extension of Kusama’s Infinity Nets motifs into three-dimensional space; “Dots Obsession—Aspiring to Heaven’s Love” (2022) is an ambitious immersive environment that includes the artist’s signature mirrored spaces and polka dots as well as suspending balloons to provide a kaleidoscopic perceptual experience; and two large sculptures titled “Pumpkin” (2022) are also be available for public viewing. Born in 1929 in Matsumoto, Japan, Kusama grew up as the youngest of four children in an affluent family. However, her childhood was less than idyllic. Her parents were the product of a loveless, arranged marriage. Her absent father, emasculated by the fact that he had to take his wife’s surname as a condition of marrying into the wealthy family, spent most of his time away from home womanizing, leaving his angry wife to physically abuse and emotionally torment her youngest child. She would often send her daughter to spy on her father’s sexual exploits, the mental trauma of which caused Kusama to have a permanent aversion to sex and the male body. At the age of ten Kusama began experiencing vivid hallucinations in which flowers would speak to her and patterns in fabric would come to life and consume her. She began to draw these visions as a therapeutic outlet, providing her with solace and control over the anxiety that tormented her. When Kusama was 13 years old she was sent to work in a military factory sewing parachutes for Japan’s World War II efforts. Her adolescent years were spent in the darkness of the factory listening to air-raid sirens and the sounds of army planes flying overhead. The horrors of war would have a lasting effect on her, leading Kusama to create numerous anti-war works, and to also value individual and creative freedom. Her experience at the factory also provided her with the utilitarian ability to sew, which would prove useful when she began creating her soft sculptures in the 1960s. Disobeying her mother, who wanted her to simply be an obedient housewife, Kusama studied art in Masumoto and Kyoto. During this time in Japan, there was a movement to reject the influences of Western culture so Kusama was forced to only study Nihonga, which consisted of creating paintings using 1000 years old traditional Japanese techniques and materials. Her artistic talent was apparent at even a young age, and Kusama’s work was shown in exhibitions all over Japan. However, the stifling conservative Japanese culture and her abusive mother proved too much for Kusama, and in 1957 she moved to the United States, settling in New York City in 1958. Before she left, Kusama’s mother handed her some money and told her “to never set foot in her house again.” In response, Kusama angrily destroyed hundreds of her works.

Once in the United States, Kusama was free to explore her artistic expression that was censored while living in Japan. “For art like mine, [Japan] was too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women. My art needed a more unlimited freedom, and a wider world.” With the help of Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom Kusama had started a correspondence and friendship with while still in Japan, she was able to secure exhibitions and some sales, leading to interest in her work right from the start. But there was also a fascination with the foreign artist herself, and she struck up a deep relationship with fellow Minimalist artist, Donald Judd, who admired her work so much that he purchased one of her first Infinity Net paintings. The middle-aged assemblage artist, Joseph Cornell was also infatuated with Kusama, often writing her love letters and sketching her in the nude. Because of her anxieties and fear of sex, both relationships, while very close, were strictly platonic. Cornell shared her sexual aversion and Kusama once remarked that “(Cornell) hated sex. That’s why we got along so well.” Kusama and Cornell developed such a close bond that when he died in 1972 she began creating collages to both honor his work and cope with his passing. During this time Kusama worked feverishly, fully embracing the hedonist, free-spirited hippie culture of the 1960s, which also included protesting war, patriarchy, and capitalist society. Combining these themes with her own intimate anxieties, she created art that was deeply personal, but also spoke to the injustices of the times. Critics didn’t know what to make of this innovative art, and soon the struggling artist went from obscurity to notoriety. Her fame rivaled that of some of the most famous Pop artists, and Kusama enjoyed the attention. Judd once recalled that while at a friend’s house, Kusama grabbed a pregnant cat and sucked one of its nipples in order to draw attention to herself. Yet, this unapologetic and admitted quest for fame might also be seen as an effort to boldly self-validate her existence and to claim her identity in opposition to the obstacles placed upon her by her family’s early denial of her career and her battle with mental illness. Kusama’s artistic output during this 15-year period was prolific and diverse, experimenting with various mediums such as drawing, painting, sculpture, performance, fashion, writing, and installation. She would sometimes work up to 50 hours without rest. Eventually the workload coupled with a lack of financial security and Cornell’s death took its toll, and in 1973 she moved back to Japan to seek treatment for her mental exhaustion and declining physical health. She began focusing on her surreal writing and avant-garde clothing line. In 1977, after being diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive neurosis, Kusama checked herself in to the Seiwa Mental Hospital and has been living and working there by choice ever since. When Kusama moved back to Japan in the early 1970s she was all but forgotten by the Western art world. Even in Japan she was mostly known for her violence-soaked writings. That changed in 1993 when she was invited to represent Japan at the 45th Venice Biennale. The acclaimed installation of one of her Infinity Mirror Rooms containing dotted pumpkins, coupled with the artist’s performances alongside the exhibition, renewed the interest and appreciation for her work, along with the interest in the quirky artist herself. Kusama still seeks the limelight and continues to insist on being photographed with her work. Wearing her signature red wig and polka dot garments of her own making, Kusama’s personality has become just as infatuating as her art. In 2008, one of Kusama’s Infinity Nets, the same one once owned by Judd, set new art auction price records for a living female artist and led to collaborations with luxury fashion retailers, like Marc Jacobs and Louis Vuitton. The woman, whose art once protested capitalism and materialism, now fully embraces it.

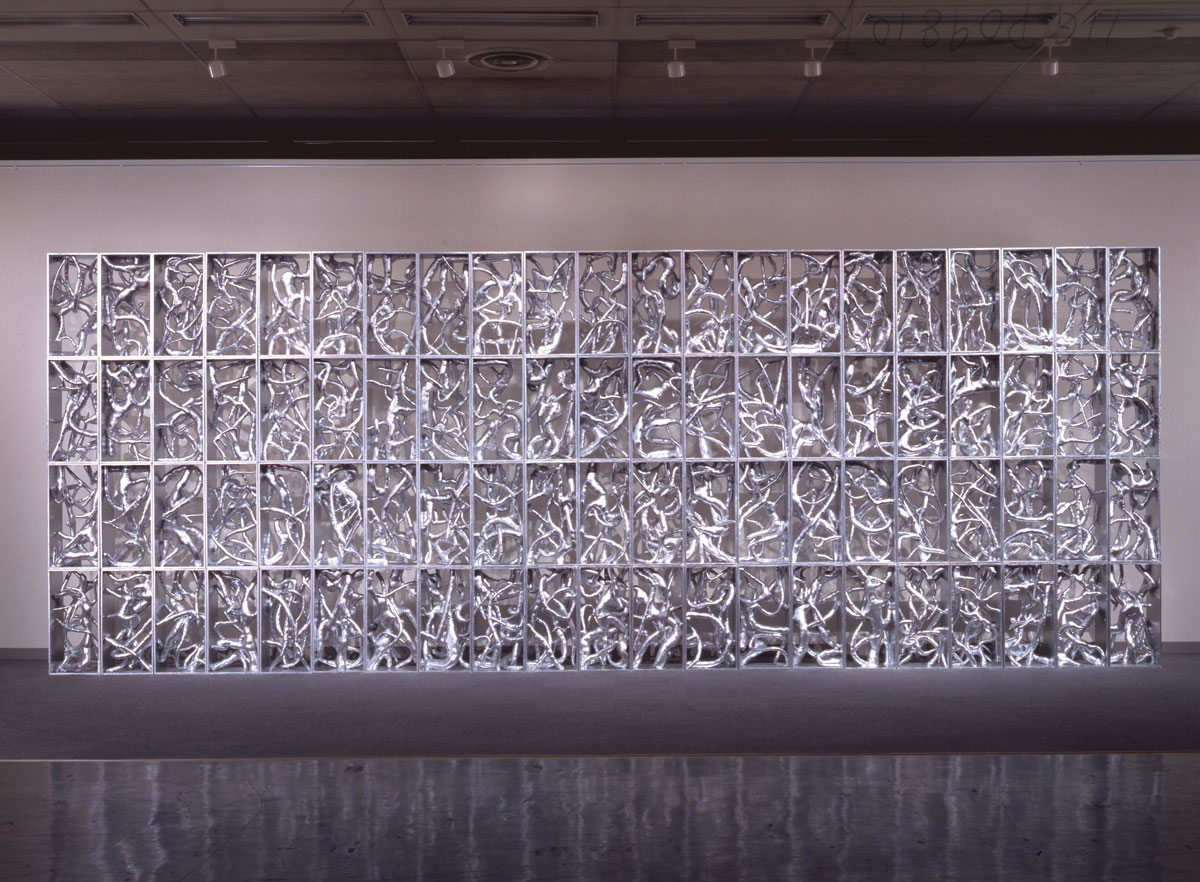

Photo: Shooting Stars, 1992. Mixed media. Niigata City Art Museum. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Photo by Norihiro Ueno, 1992. Image courtesy of Niigata City Art Museum

Info: M+ Museum, West Kowloon Cultural District, West Kowloon, Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong, Duration: 12/11/2022-14/5/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, Fri 10:00-22:00, www.mplus.org.hk/

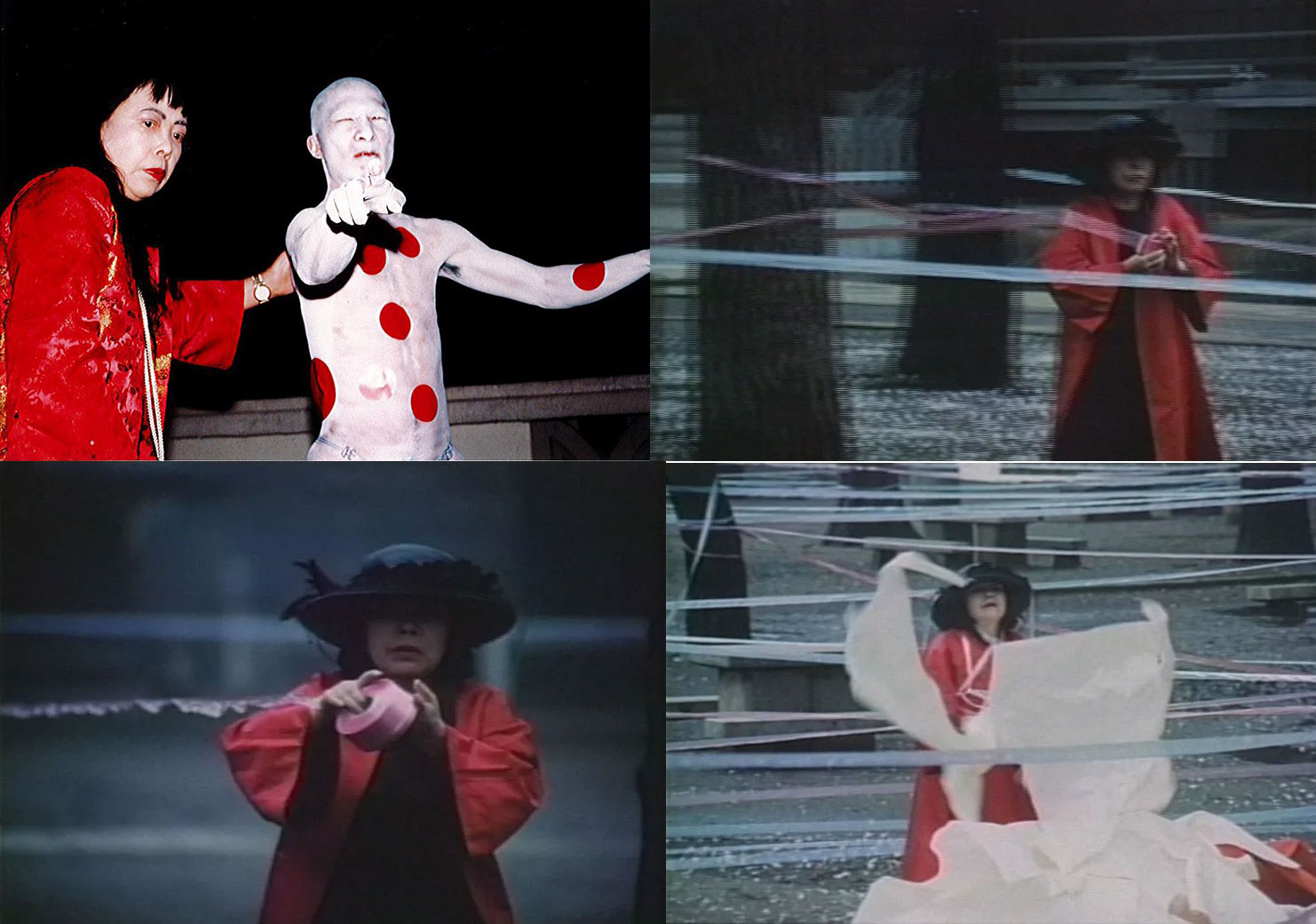

Upper Right & Down: Flowers of Basara (stills), performance at Kuhonbutsu Jōshin-ji temple, Tokyo, 1985. Digital video (colour, silent), 1 min. 20 sec. Collection of the artist. © YAYOI KUSAMA