ART CITIES: Cologne-Green Modernism, The New View of Plants, Part II

The exhibition “Green Modernism: The New View of Plants” takes us back to the early twentieth century and examines the depiction of plants in the visual arts and how they were viewed in botany and society in general. After all, as plain as potted plants in pictures may appear at first glance, and as matter-of-fact as botanical reports read, they always also attest to the contradictions, fears, longings, and ideologies of the modern age (Part I).

The exhibition “Green Modernism: The New View of Plants” takes us back to the early twentieth century and examines the depiction of plants in the visual arts and how they were viewed in botany and society in general. After all, as plain as potted plants in pictures may appear at first glance, and as matter-of-fact as botanical reports read, they always also attest to the contradictions, fears, longings, and ideologies of the modern age (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

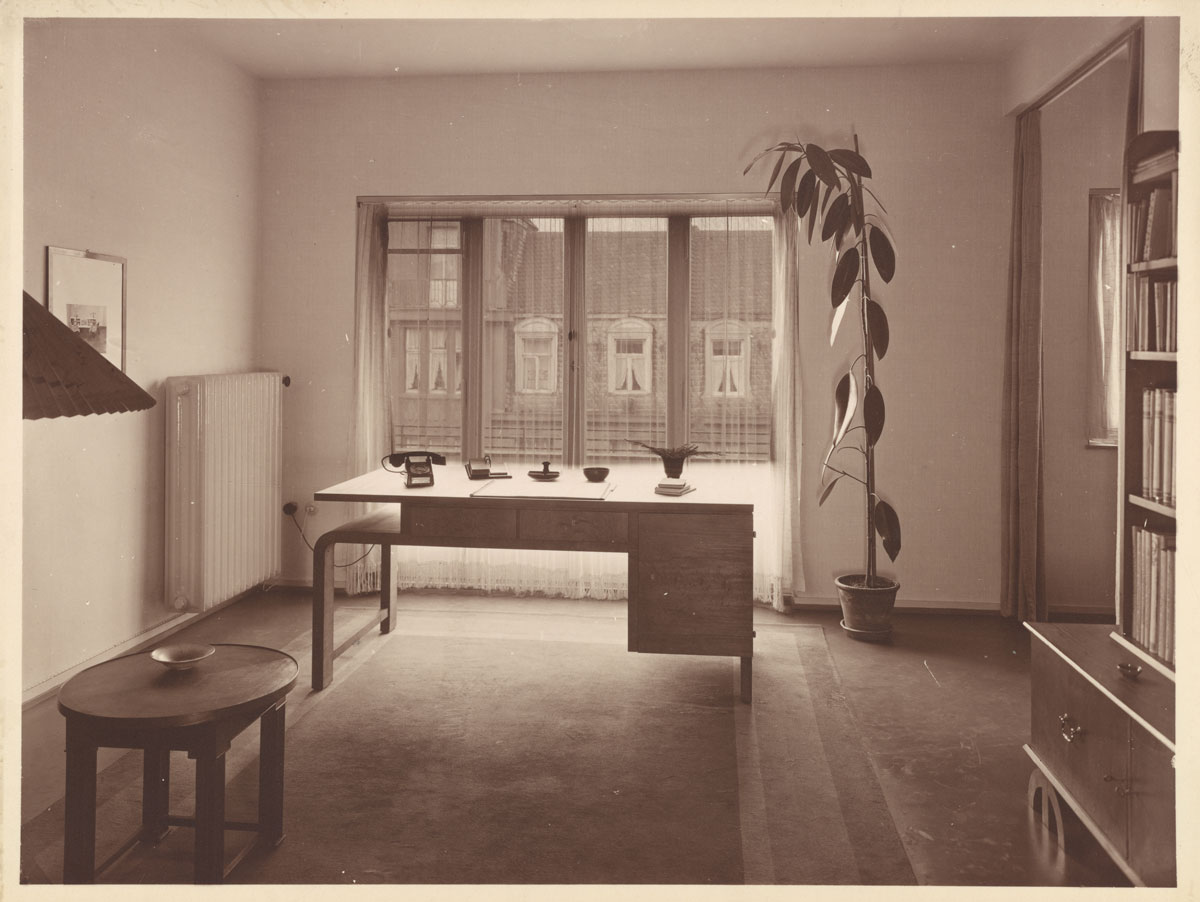

Photo: Museum Ludwig Cologne Archive

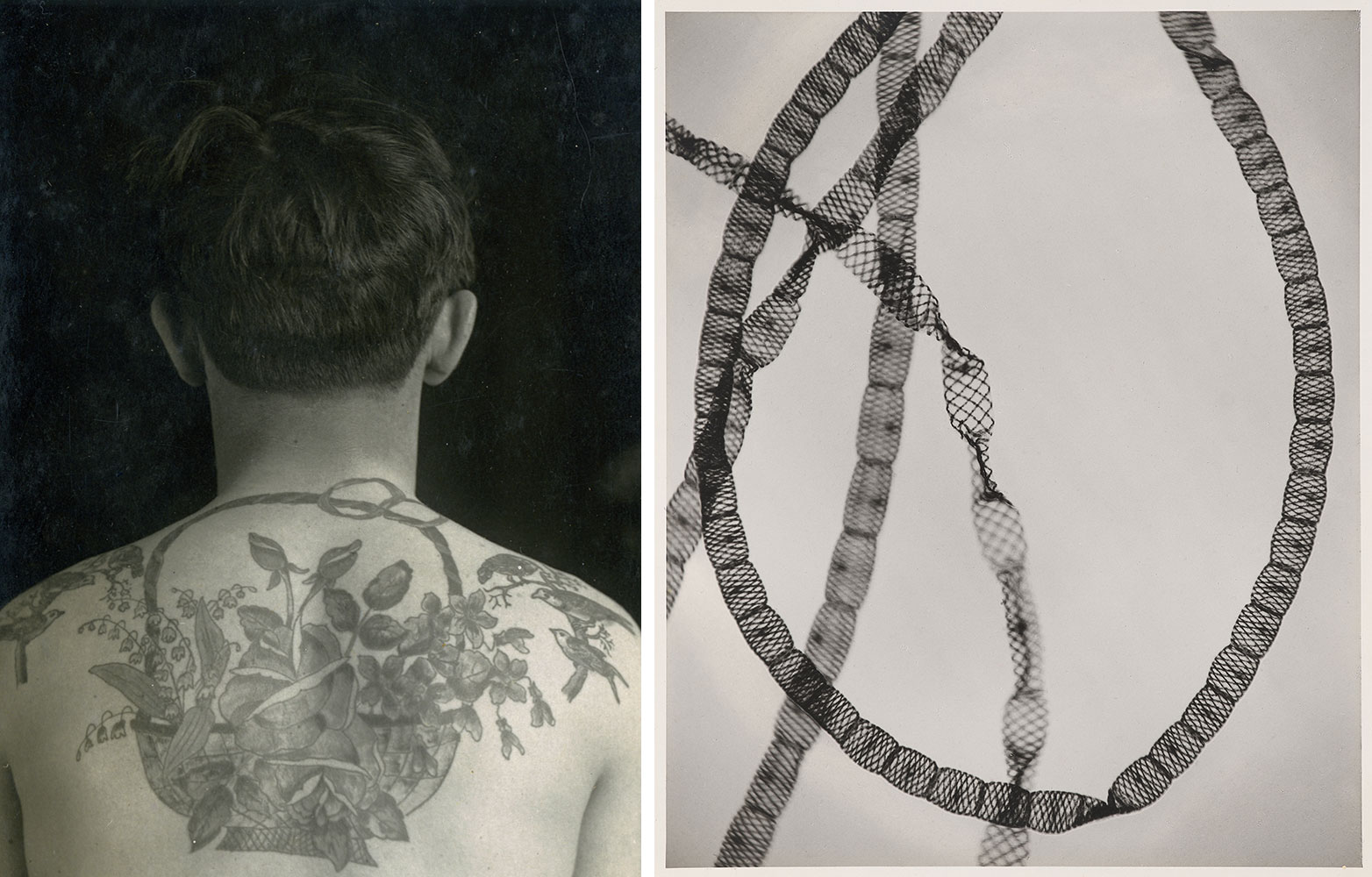

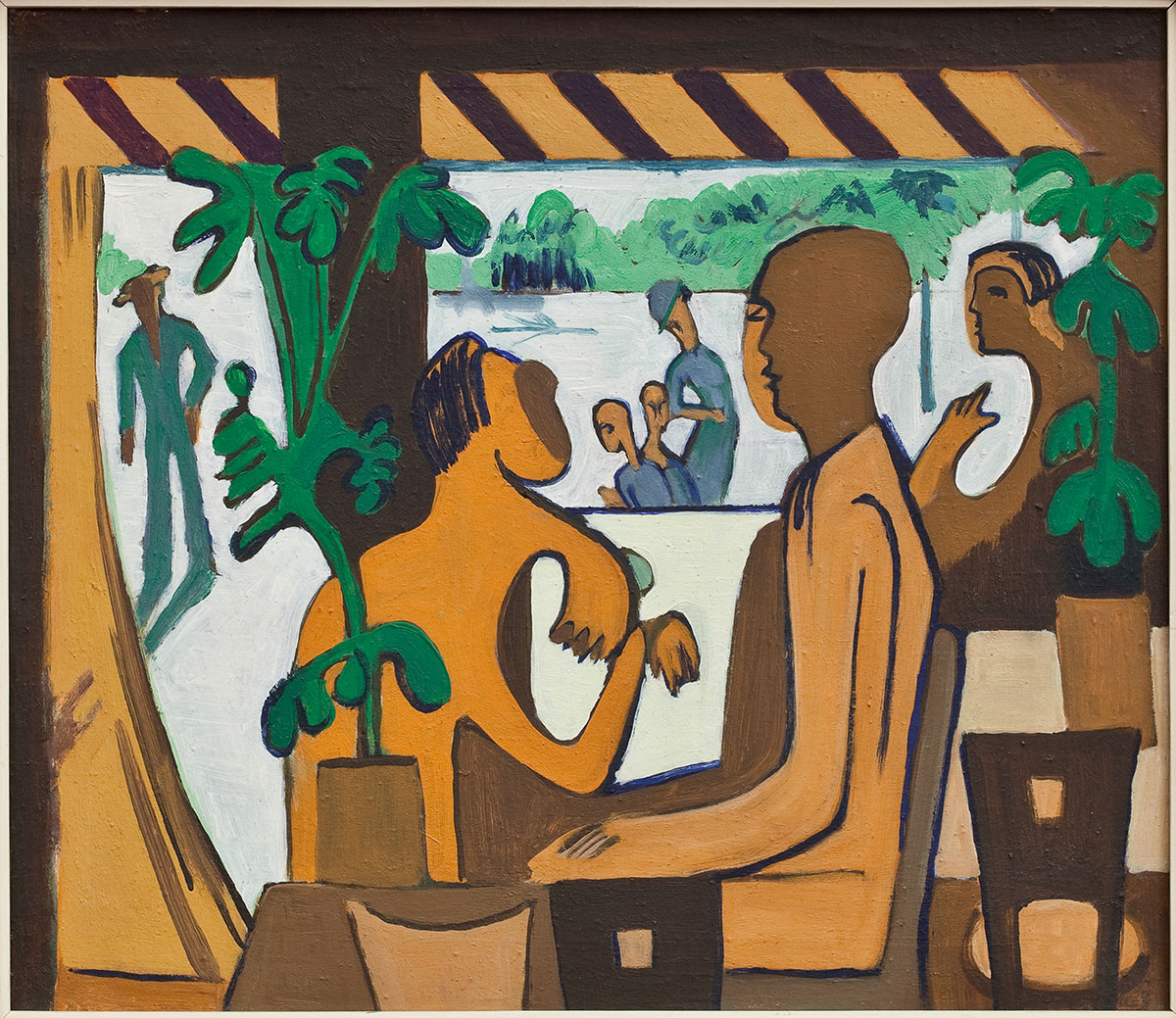

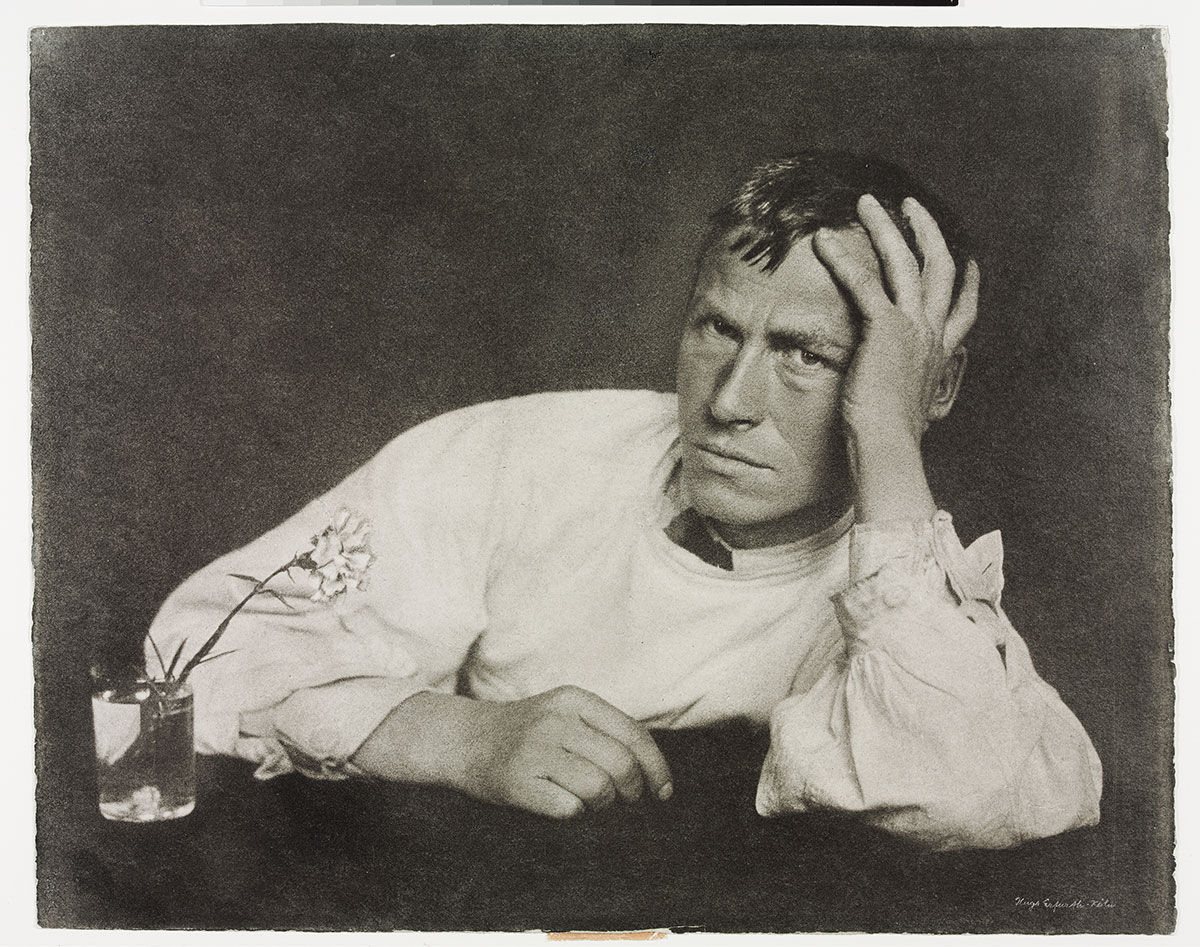

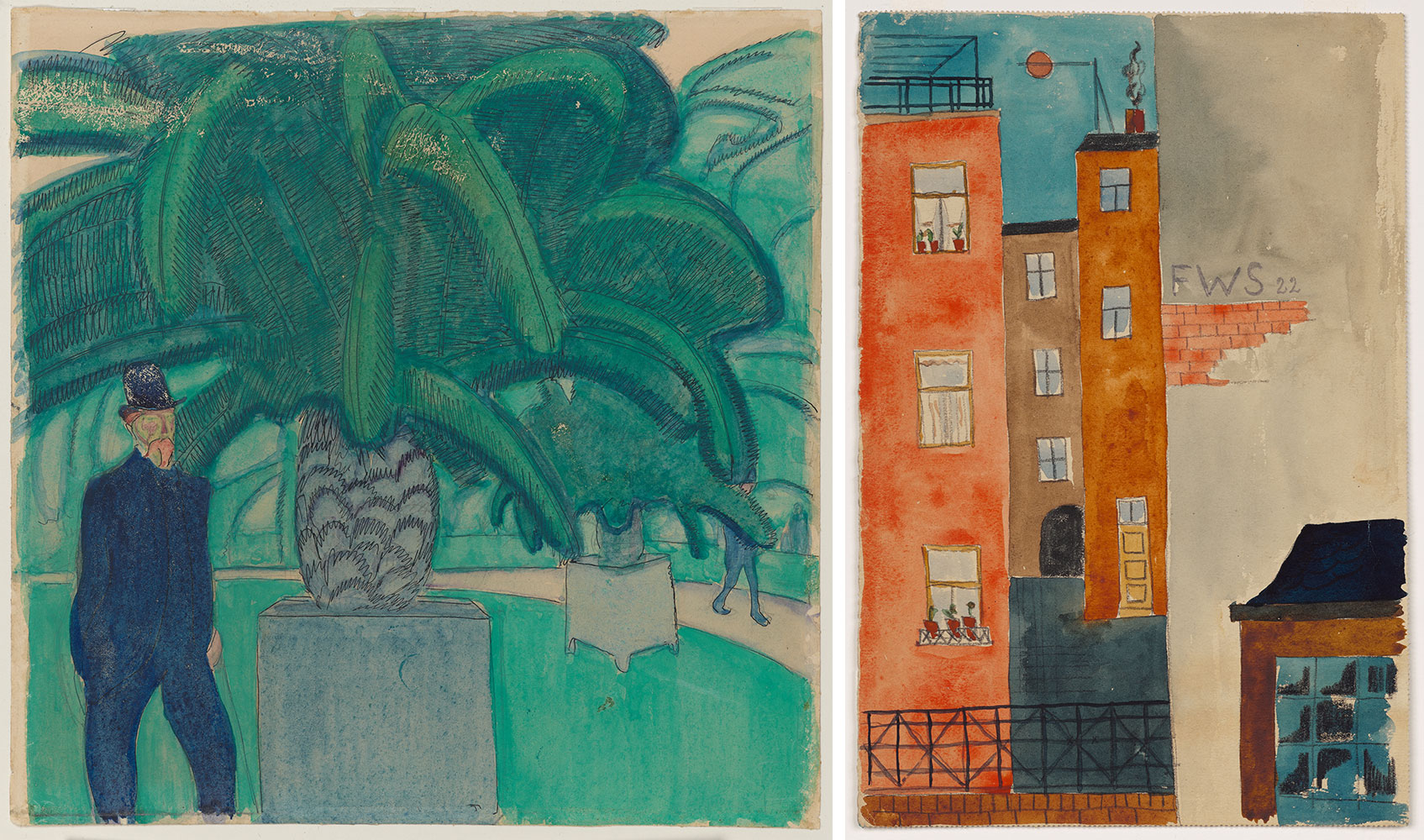

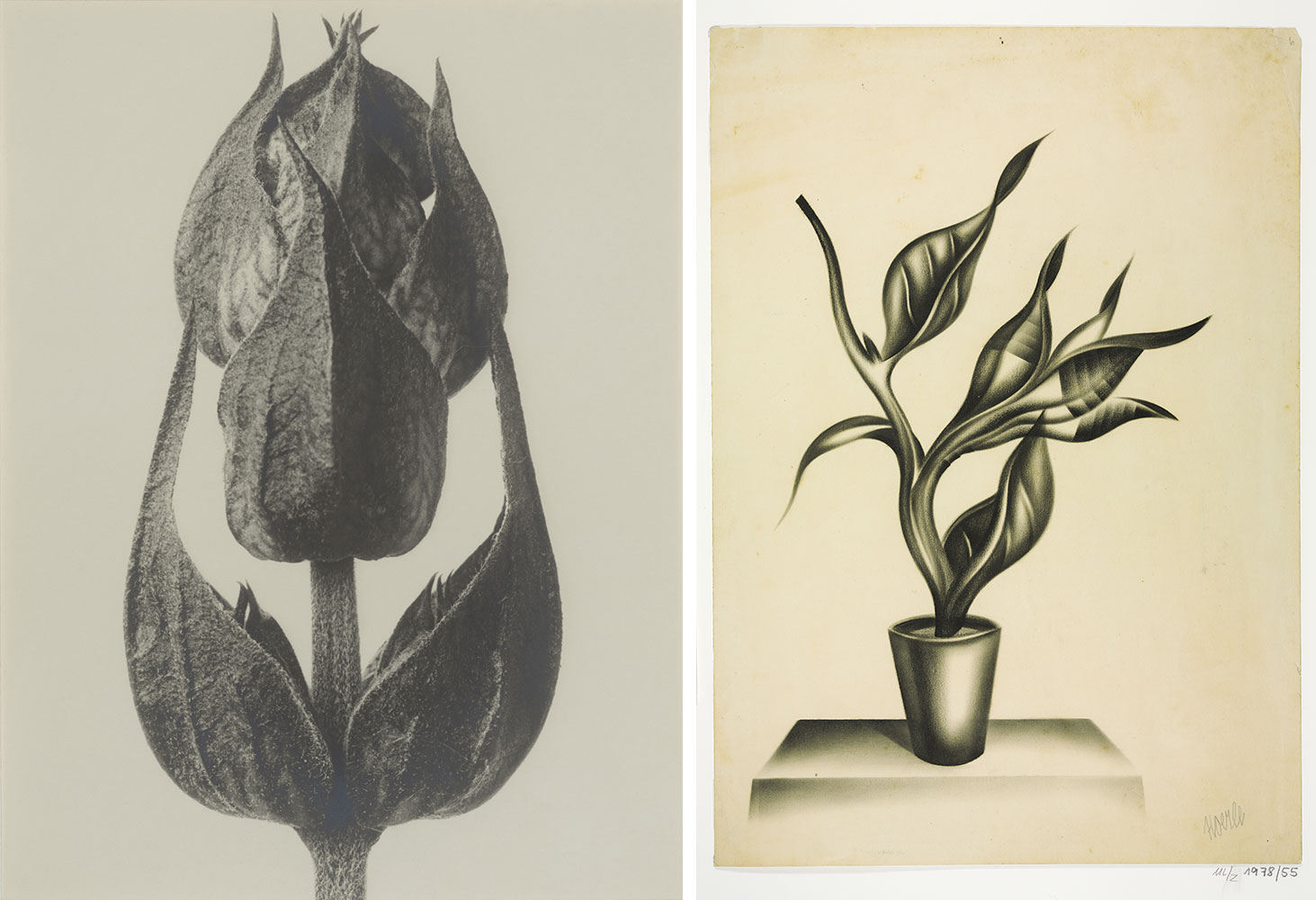

The exhibition “Green Modernism: The New View of Plants” focuses on this topic with around 130 exhibits in four chapters: The Plant as the Other: The Comedian Harmonists sang about a plant that was extraordinarily popular at the beginning of the twentieth century. Cactuses were “hunted” in the Americas in order to be grown and sold on the German market. Like a big game hunter, the plant collector Curt Backeberg had a portrait of himself taken in white clothing with a lasso in his arm next to a meter-high cactus. In this respect, indoor gardens, which were cultivated, sung about, photographed, and painted, were colonial gardens, and thus the private continuation of the palm houses that had become popular in the nineteenth century. Those who wanted to be modern filled their homes with cactuses, rubber trees, and other plants that grew outdoors only in warmer climates, but could flourish indoors thanks to coal heating and large windows. Aenne Biermann photographed her own collection of cactuses, Albert Renger-Patzsch made recommendations about photographing cactuses for amateur photographers, and the art historian and collector Rosa Schapire had Karl Schmidt-Rottluff design a “cactus home” for her. Meanwhile, tubular-steel furniture was shown next to cactuses in interior design magazines as a matter of course. The Appropriated Plant: After 1918, the New Woman, wearing floral dresses, continued to pay homage to Flora, the goddess of flowers. In a time of increasing “gender disorder,” when short hair no longer marked a woman’s sexual identity and Magnus Hirschfeld conducted gender reassignment surgeries, flowers remained prominent in fashion: August Sander’s smoking garçonne Anneli Strohal wore flowers on her dress, as did Lili Elbe even before her operations. And Marlene Dietrich wore a giant flower in the buttonhole of her dark suit in a nod to the often discussed fear of the “masculinization” of modern women. The adoption of flowers as a passive lure in the service of procreation can be found in perhaps its most ritual form in wedding pictures, in the hair and hands of the brides. Floral elements were also present underneath people’s clothing, namely as tattoos, as Christian Warlich’s tattoo art from the 1920s shows. The Plant as Form and Color: The photographer Karl Blossfeldt was not interested in the names and functions of plants. What intrigued him was their form, which he revealed by pruning the plants he photographed—often to the point of nonrecognition so they could be used by artisans as reference material for their designs. Plants even served as “building material” for professional florists. Others, such as the artist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, used flowers, including the poisonous larkspur, to add an accent of color to a painting. The Plant as Relative: The philosopher Walter Benjamin was not the only one who was fascinated by photographs of plants under the microscope and time-lapse recordings. Cinemas were packed with audiences for the film “Das Blumenwunder” (1926) directed by Max Reichmann, which presented plants in a completely new way. These miraculous images came from the time-lapse laboratory recordings of experiments with the first artificial fertilizer, which was developed to help feed the world’s growing population. The fact that plants are alive, move, have a pulse, and can grow tired was described by the physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose in his popular book “Plant Autographs and Their Revelations”. At the same time, the biosophist Ernst Fuhrmann dramatically lit and staged plants for his photography book “Die Pflanze als Lebewesen”. The boundaries between lifeforms had become more fluid, and so it is not surprising that horror fantasies about plants can also be found in film and literature of the Weimar Republic, such as carnivorous plants, which were only recognized in botany with Charles Darwin.

Works among others by: Hans Arp, Max Baur, Arthur Benda, Aenne Biermann, Karl Blossfeldt, Otto Dix, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Hugo Erfurth, Max Ernst, Otto Feldmann, Ernst Fuhrmann, Albert and Richard Theodor Gottheil, Erich Heckel, Heinrich Hoerle, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Werner Mantz, Franz Pichler Jr., Anton Räderscheidt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Ludwig Ernst Ronig, August Sander, Karl Schenker, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Richard Seewald, Friedrich Seidenstücker, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Renée Sintenis, Carl Strüwe. Also featuring: Marta Astfalck-Vietz, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Comedian Harmonists, Lili Elbe, Wilhelm Murnau, Max Reichmann, Christian Warlich, and others.

Photo Left: Christian Warlich, Tattooed person, 1920s, Museum of Hamburg History. Right: Carl Struwe, Construction of a chain alga as a chlorophyll factory, 1928, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Carl Strüwe Archive Bielefeld, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Info: Curator: Miriam Szwast, advised by Suzanne Pierre, Museum Ludwig Cologne, Heinrich-Böll-Platz, Cologne, Germany, Duration: 17/9/2022-22/1/2023,Days & Hours: Tue-sun 10:00-18:00, www.museum-ludwig.de/

Right: Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Backyard, 1922, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Right: Otto Dix, Martha Dix, 1926, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln/Britta Schlier

Right: Alfred Eisenstadt, Marlene Dietrich, around 1928, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Time-Life Syndication, New York, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Right: Heinrich Hoerle, Pot Plant, 1920s, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Right: Folkwang-Auriga Verlag, Mimosa pudica, Blätter, um 1930, Museum Ludwig, Köln, Reproduktion: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln/Marc Weber