TRACES: Park Seo-Bo

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Park Seo-Bo (15/11/1931-14/10/2023 ), who is considered one of the leading figures in bringing the European Modernist concept of art to Korea in the late ‘50s after the Korean War. The expressionist tendency at that time was partially influenced by French l’art informel in an attempt to bring Eastern calligraphy into contact with Western forms. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Park Seo-Bo (15/11/1931-14/10/2023 ), who is considered one of the leading figures in bringing the European Modernist concept of art to Korea in the late ‘50s after the Korean War. The expressionist tendency at that time was partially influenced by French l’art informel in an attempt to bring Eastern calligraphy into contact with Western forms. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi MIchalarou

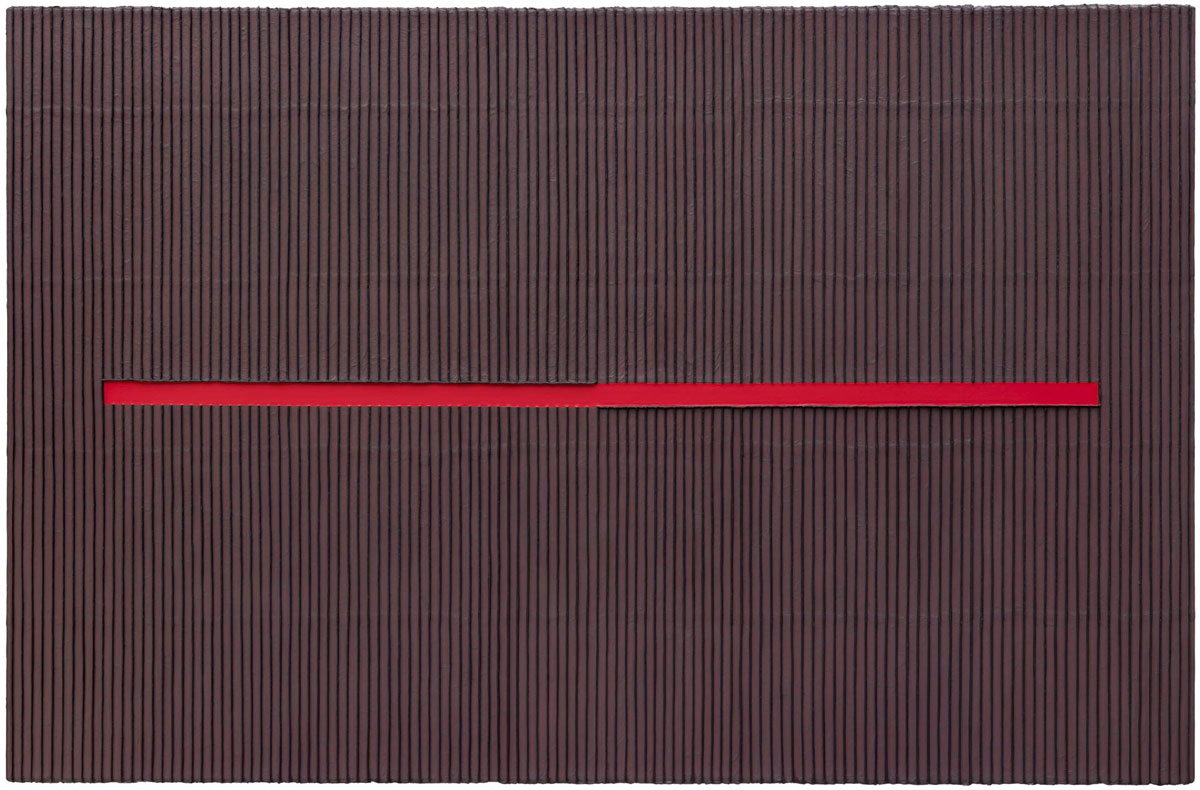

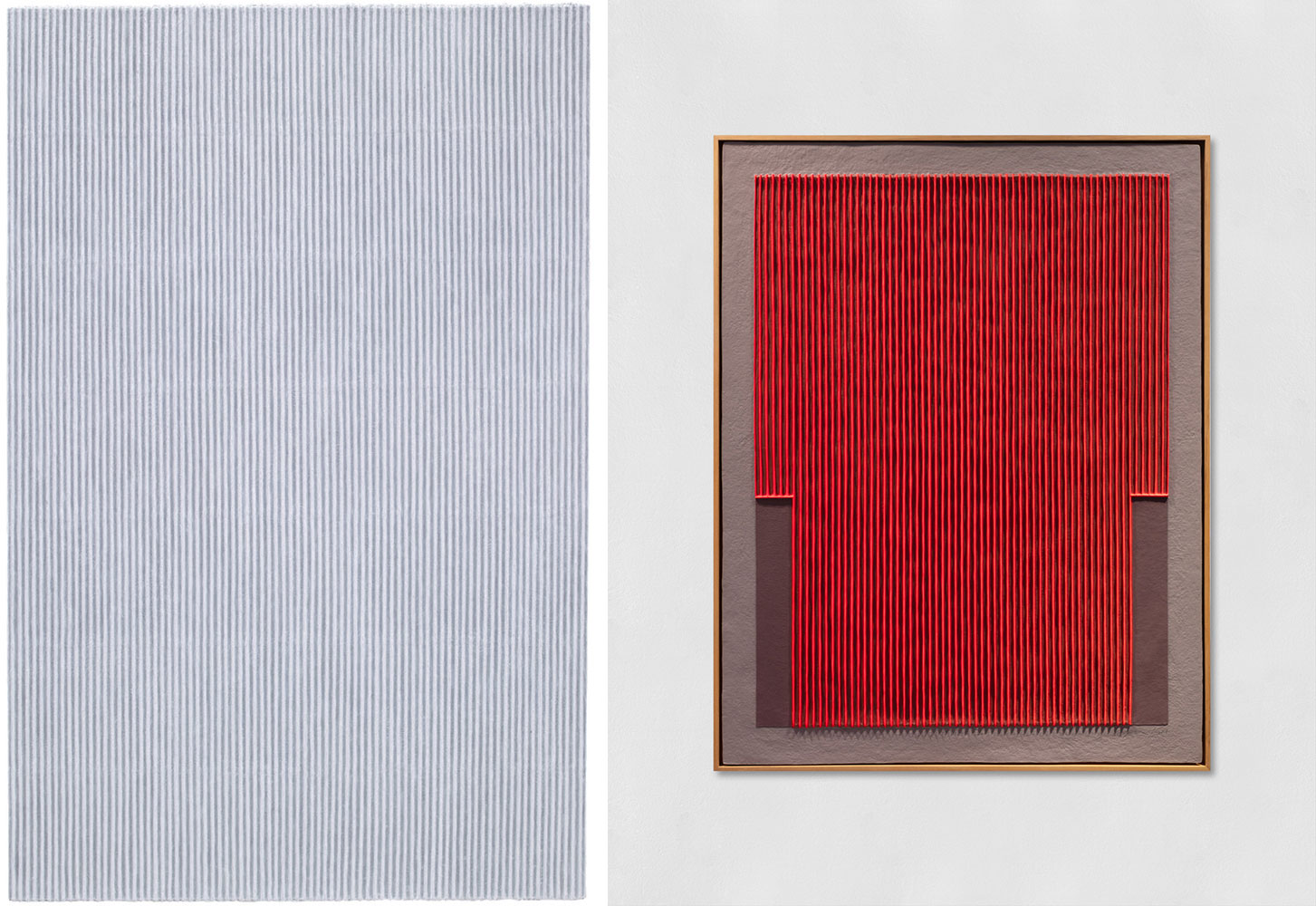

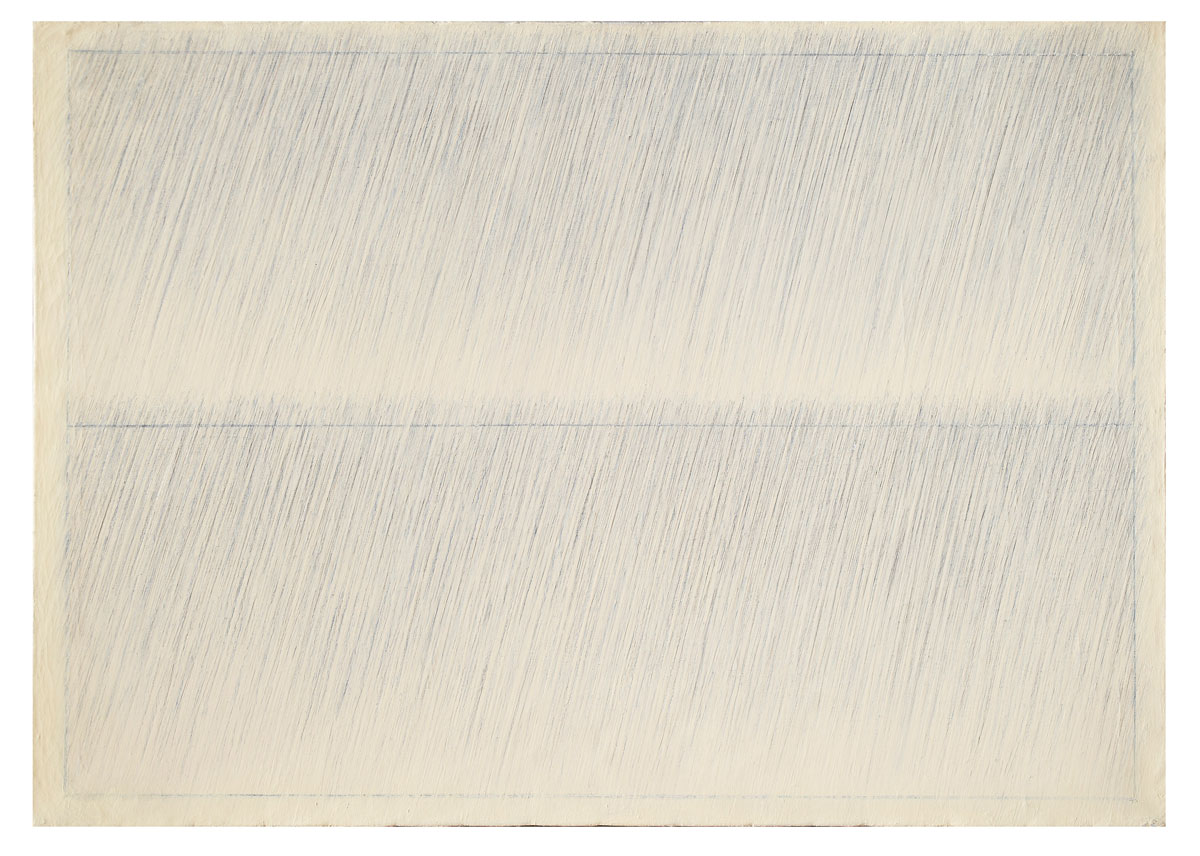

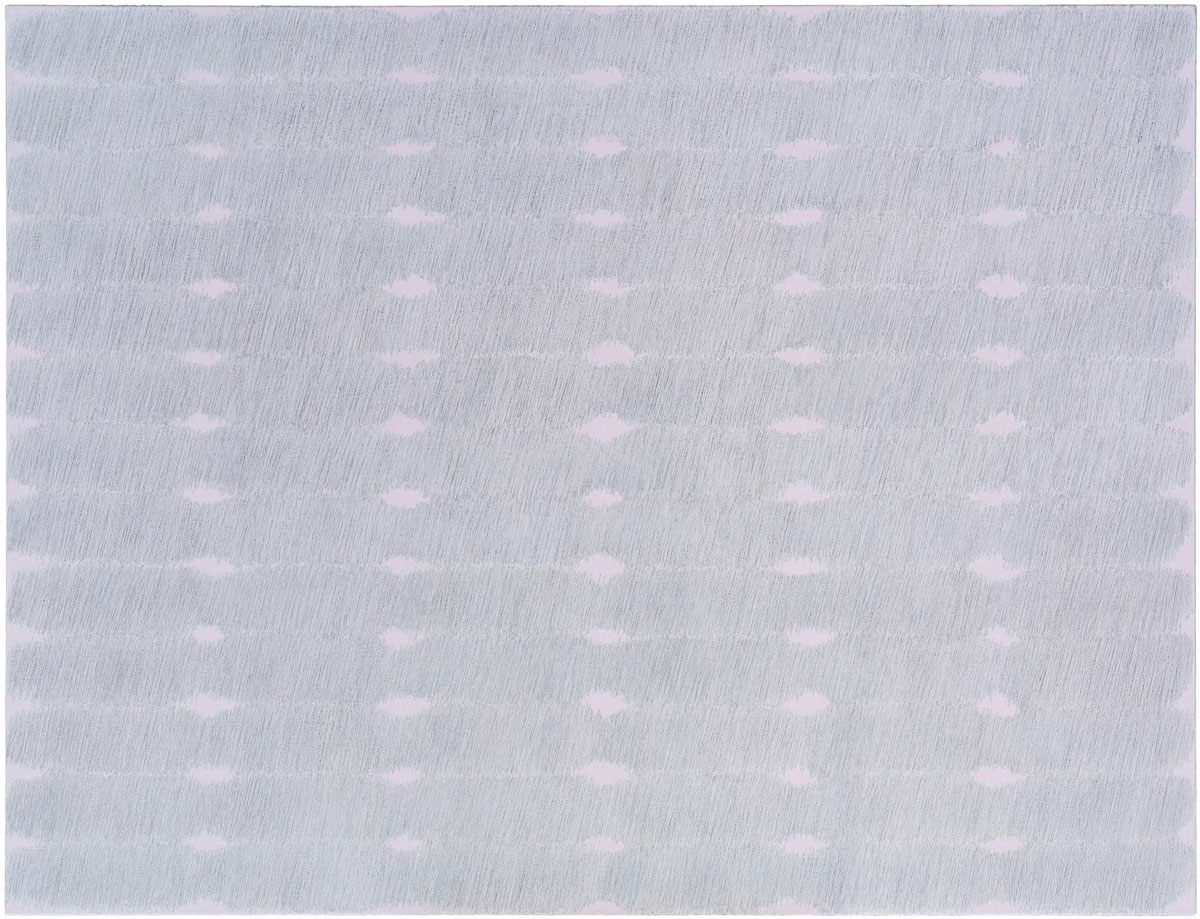

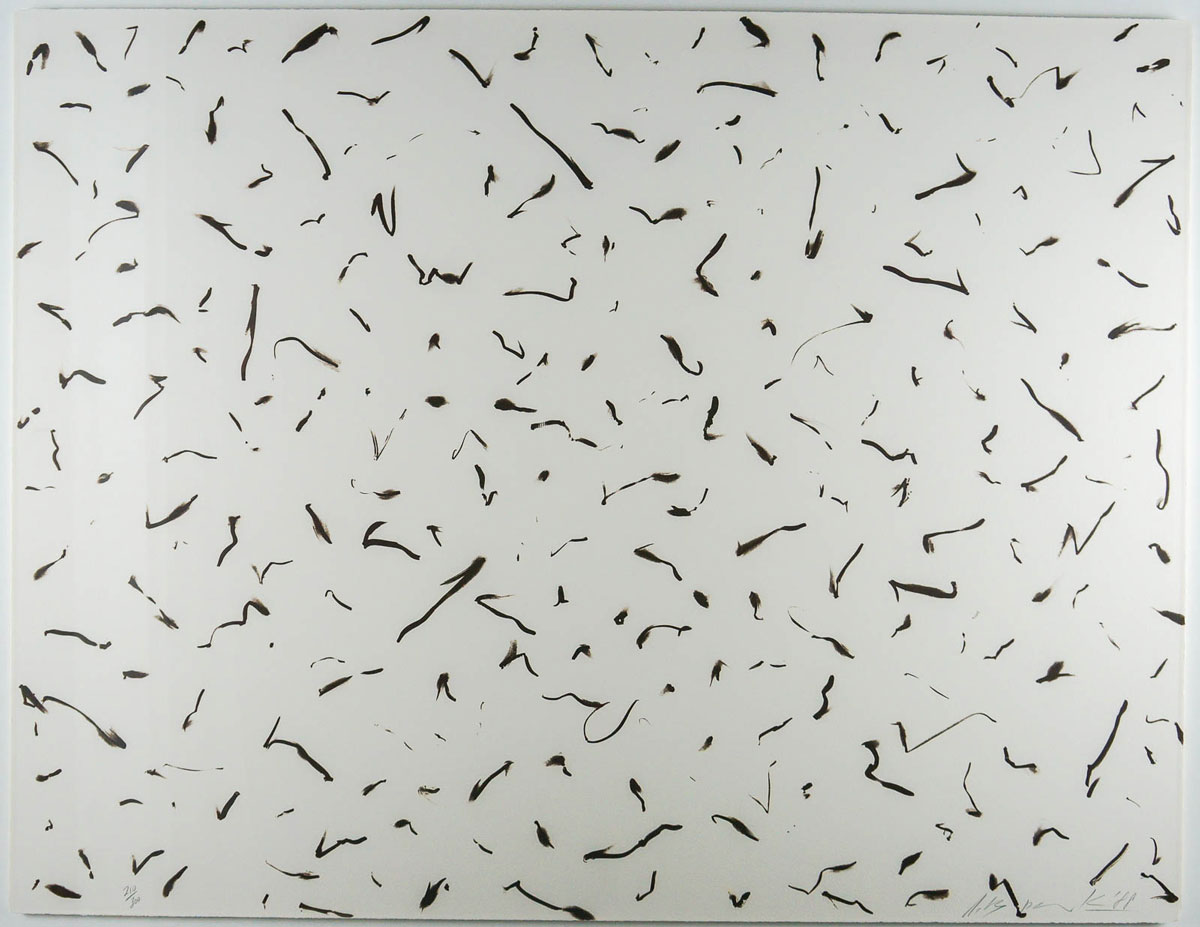

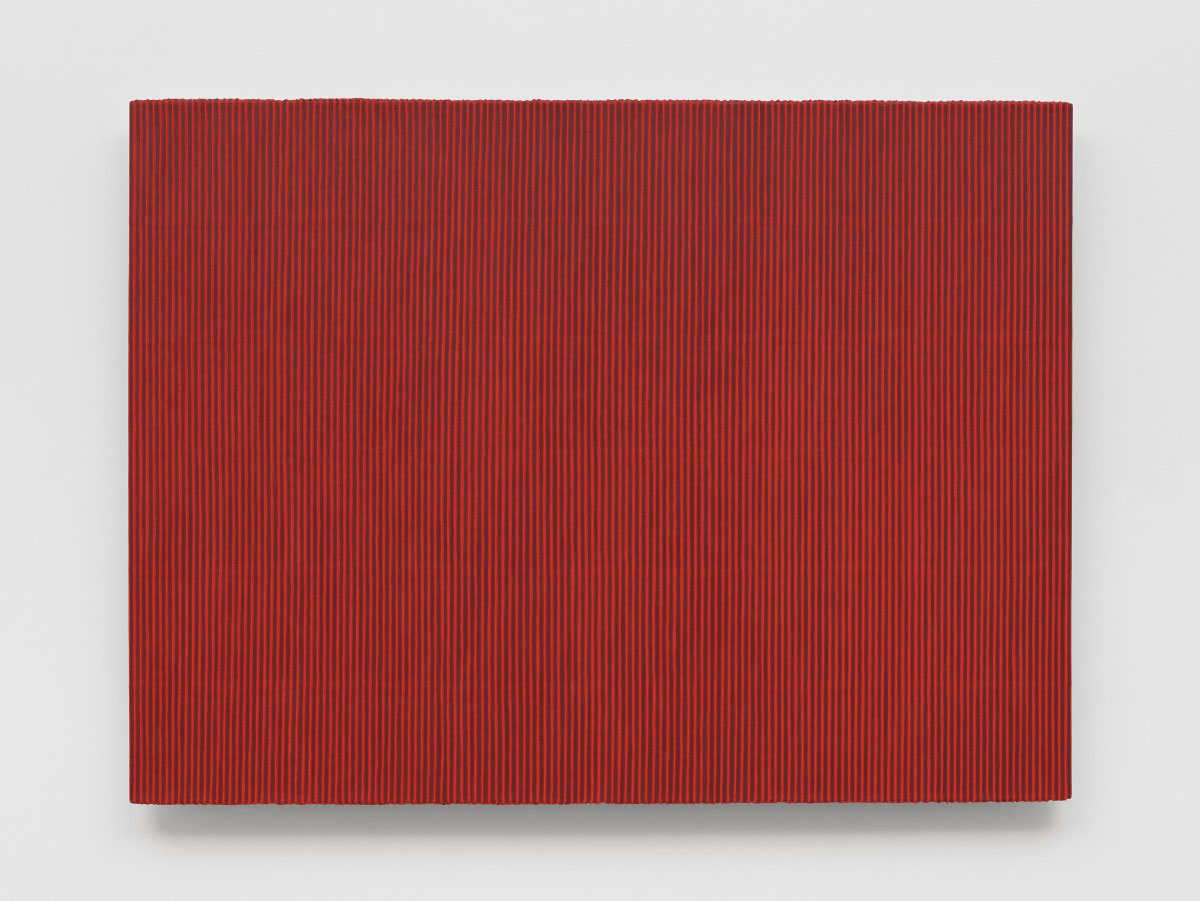

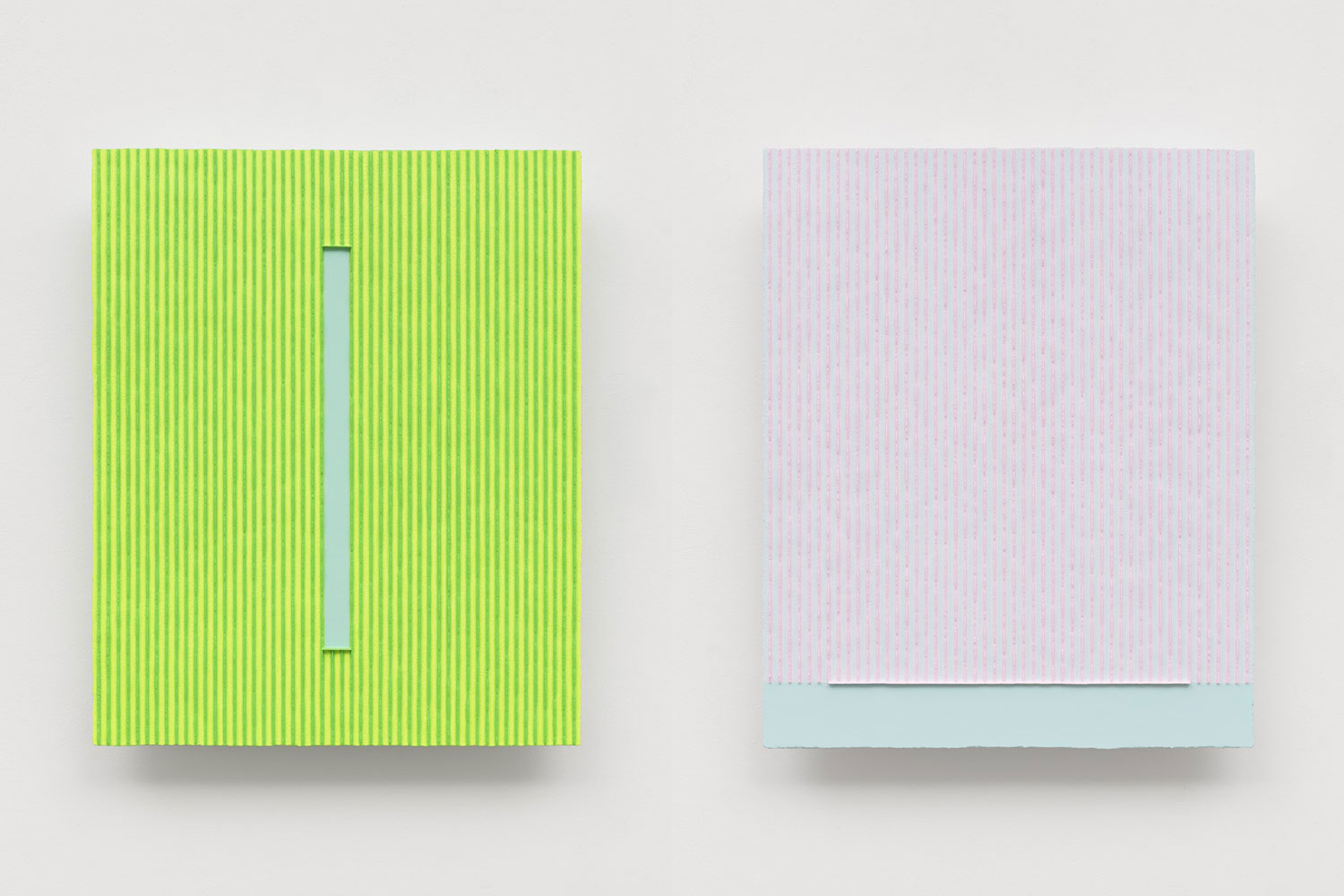

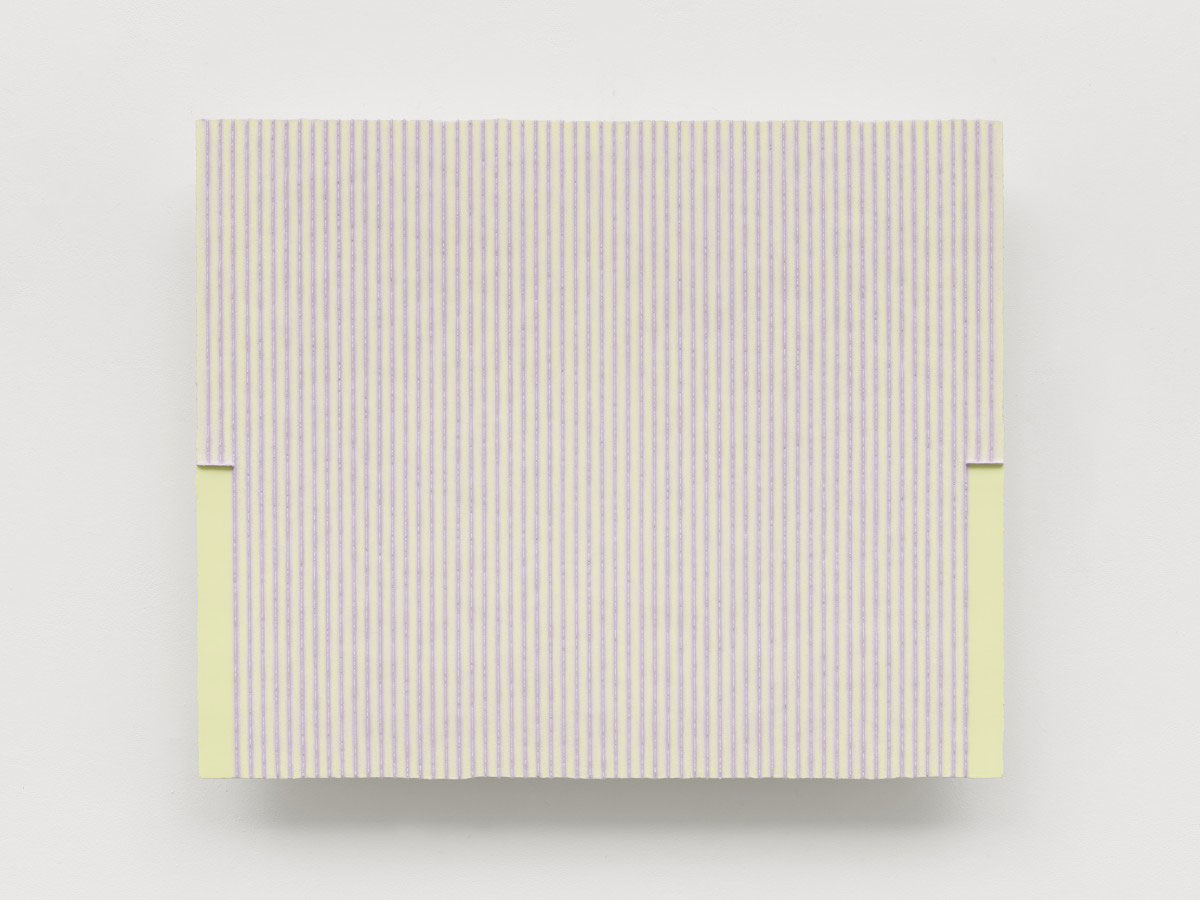

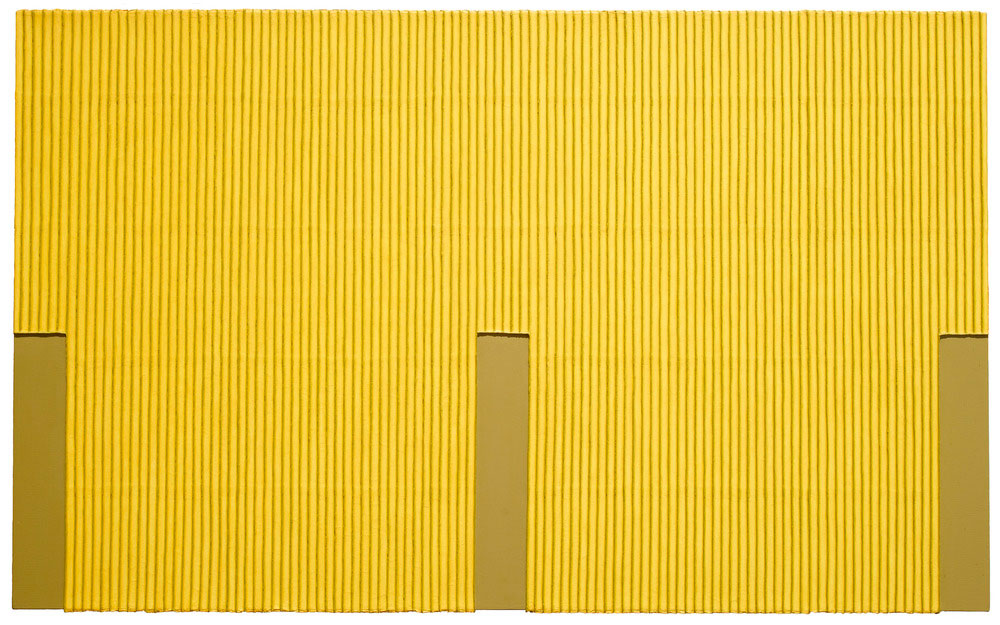

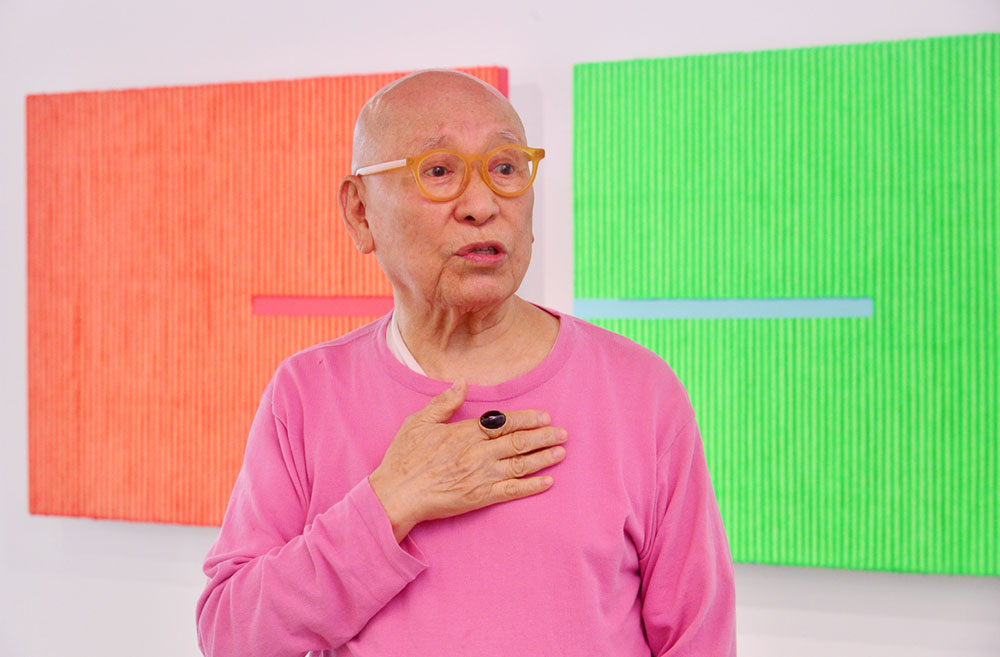

Park Seo-Bo was born in Yecheon in Kyoungbuk Province, Korea and grew up in Ansung in Kyoungki Province. Although his father wanted him to study law, Seo-bo insisted on his pursuing art. In spite of his father’s opposition, he entered Hongik University to study oriental painting under the lead of Yi Eungro. He narrowly survived the war time chaos, experiencing his father’s abrupt death, drafts both by North Korean and South Korean forces and long winter evacuating on foot from his hometown Anseong to Masan. Seo-bo barely managed to go back to school in 1952. Hongik University temporarily moved to Busan during the war time. He enrolled for the second year and changed his major to western painting because his professors of oriental painting were all gone. He received a prize at the Korean National Art Exhibition in 1954 as a student and again in 1955. However, the National Art Exhibition had been never free of troubles since it was established in 1949. Seo-bo declared objection to the National Art Exhibition with three of his school friends and opened their own group exhibition in 1956. The work “Painting no.1”(1957) resolutely signals Park Seo-Bo’s vanguard attitude towards the making of idealistic images of the Kukjeon artists. “Primordialis No.62-3” and “Primordialis no.1-62” in 1962, and “Hereditarius no.1-68” in 1968 provide critical clues in analysing a conceptual transition of his works that lay a coherent foundation for his oeuvre. He left for Paris when he was selected as a national representative young artist for the Young Painters of the World in Paris in 1961. It was a residency program organized by the French National Committee of International Association of Art with support of UNESCO. During his time in Paris, his artistic tendency and outlook changed significantly, which ultimately resulted in his exiting the Art Informel scene toward his own artistic formulation, the “Primordialis” series in 1962. When he came back from Paris to Seoul, he started teaching at Hongik University, Seoul. However, he became a scapegoat in dynamics between professors and the private school foundation, which led to his resignation. Toward the end of the 1960s, Park began experimenting in new forms, the “Hereditarius” series. Then in June 1973 at Tokyo Gallery, Park began his ongoing journey through the “Ecriture” series. As he said “I painted nothing, my work had no form, no emphasis, and no ins-and-outs, except for the pure vibration coming out of not doing anything – an action through non-action.[…] Anyone can draw lines, but my lines are the endemic phenomenon which takes place only in me. I feel and reciprocate the resistance of the bouncy canvas, then I feel replete with an impulsive sensation. In this way I keep being gravitated into the canvas. It is similar to cultivating the religious spirit[…]. I started from where there was no form, or no image – where it was impossible to express”. In the early works, Park used repeated pencil lines incised into a still-wet monochromatic painted surface. In 1970, he was called back to professorship at Hongik University and served for education until he retired in 1997. He was the dean of the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Hongik University from 1985 to 1986 and the dean of College of Fine Arts from 1986 to 1990. He received an honorary doctorate from the same university in 2000. In the 1980s the works expand upon this language through the introduction of hanji, a traditional Korean paper hand-made from mulberry bark, which is adhered to the canvas surface. This development, along with the introduction of color, enabled an expansive transformation of his practice while continuing the quest for emptiness though reduction. “Ecriture” was Seo-bo’s attempt to control his extreme energies. Drawing lines over and over again and then covering them with white paint was a kind of practice in self-restraint, a meditation that he pursued as a result of something Kim Iryeop told him in 1955. Seo-bo had to focus and condense his energy to achieve this, drawing a single line at one breath for example, or controlling the movement of his arm to make a straight line. Park shifted the style of his project in the 1990s, this time creating common intervals of furrows using everyday tools, including sticks and rulers, rather than freehand movements. He also began to use lively, vita colors for the pieces of his Ecriture after his trip to Japan in 2000, where he was influenced by the colorful autumn leaves. At the beginning of the 2000s, Park thought deeply about how he could adapt to the new digital age and incorporate new technology into Ecriture., when stronger colors began to appear, starting with red. His compositions became more systematized and gained more consistency than before. The work became more rational as a whole. Later, a generation of artists known for their meditative, process-oriented abstraction, including Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, Ha Chong-Hyun, Kwon Young-woo, Yun Hyong-keun and would be formalized as the “Dansaekhwa”* (meaning “monochrome painting”) artists by critic Yoon Jin Sup in 2000. In the past decade, modernist movements in countries across Asia have started to receive the attention of international institutions, art historians, curators, and private collectors. While Park’s works and those by other Dansaekhwa artists have soared in visibility and price, his practice has continued to evolve. We corresponded as Park approached his 90th birthday in late 2021, before the opening of a new exhibition at Kukje Gallery in Seoul in September, where he was debuting a suite of recent Ecriture paintings, including several in vivid new colors. In February 2022, Park revealed his advanced diagnosis of lung cancer and his decision to not seek treatment. He died from lung cancer on 14 October 2023, at the age of 91.

Park Seo-Bo was born in Yecheon in Kyoungbuk Province, Korea and grew up in Ansung in Kyoungki Province. Although his father wanted him to study law, Seo-bo insisted on his pursuing art. In spite of his father’s opposition, he entered Hongik University to study oriental painting under the lead of Yi Eungro. He narrowly survived the war time chaos, experiencing his father’s abrupt death, drafts both by North Korean and South Korean forces and long winter evacuating on foot from his hometown Anseong to Masan. Seo-bo barely managed to go back to school in 1952. Hongik University temporarily moved to Busan during the war time. He enrolled for the second year and changed his major to western painting because his professors of oriental painting were all gone. He received a prize at the Korean National Art Exhibition in 1954 as a student and again in 1955. However, the National Art Exhibition had been never free of troubles since it was established in 1949. Seo-bo declared objection to the National Art Exhibition with three of his school friends and opened their own group exhibition in 1956. The work “Painting no.1”(1957) resolutely signals Park Seo-Bo’s vanguard attitude towards the making of idealistic images of the Kukjeon artists. “Primordialis No.62-3” and “Primordialis no.1-62” in 1962, and “Hereditarius no.1-68” in 1968 provide critical clues in analysing a conceptual transition of his works that lay a coherent foundation for his oeuvre. He left for Paris when he was selected as a national representative young artist for the Young Painters of the World in Paris in 1961. It was a residency program organized by the French National Committee of International Association of Art with support of UNESCO. During his time in Paris, his artistic tendency and outlook changed significantly, which ultimately resulted in his exiting the Art Informel scene toward his own artistic formulation, the “Primordialis” series in 1962. When he came back from Paris to Seoul, he started teaching at Hongik University, Seoul. However, he became a scapegoat in dynamics between professors and the private school foundation, which led to his resignation. Toward the end of the 1960s, Park began experimenting in new forms, the “Hereditarius” series. Then in June 1973 at Tokyo Gallery, Park began his ongoing journey through the “Ecriture” series. As he said “I painted nothing, my work had no form, no emphasis, and no ins-and-outs, except for the pure vibration coming out of not doing anything – an action through non-action.[…] Anyone can draw lines, but my lines are the endemic phenomenon which takes place only in me. I feel and reciprocate the resistance of the bouncy canvas, then I feel replete with an impulsive sensation. In this way I keep being gravitated into the canvas. It is similar to cultivating the religious spirit[…]. I started from where there was no form, or no image – where it was impossible to express”. In the early works, Park used repeated pencil lines incised into a still-wet monochromatic painted surface. In 1970, he was called back to professorship at Hongik University and served for education until he retired in 1997. He was the dean of the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Hongik University from 1985 to 1986 and the dean of College of Fine Arts from 1986 to 1990. He received an honorary doctorate from the same university in 2000. In the 1980s the works expand upon this language through the introduction of hanji, a traditional Korean paper hand-made from mulberry bark, which is adhered to the canvas surface. This development, along with the introduction of color, enabled an expansive transformation of his practice while continuing the quest for emptiness though reduction. “Ecriture” was Seo-bo’s attempt to control his extreme energies. Drawing lines over and over again and then covering them with white paint was a kind of practice in self-restraint, a meditation that he pursued as a result of something Kim Iryeop told him in 1955. Seo-bo had to focus and condense his energy to achieve this, drawing a single line at one breath for example, or controlling the movement of his arm to make a straight line. Park shifted the style of his project in the 1990s, this time creating common intervals of furrows using everyday tools, including sticks and rulers, rather than freehand movements. He also began to use lively, vita colors for the pieces of his Ecriture after his trip to Japan in 2000, where he was influenced by the colorful autumn leaves. At the beginning of the 2000s, Park thought deeply about how he could adapt to the new digital age and incorporate new technology into Ecriture., when stronger colors began to appear, starting with red. His compositions became more systematized and gained more consistency than before. The work became more rational as a whole. Later, a generation of artists known for their meditative, process-oriented abstraction, including Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, Ha Chong-Hyun, Kwon Young-woo, Yun Hyong-keun and would be formalized as the “Dansaekhwa”* (meaning “monochrome painting”) artists by critic Yoon Jin Sup in 2000. In the past decade, modernist movements in countries across Asia have started to receive the attention of international institutions, art historians, curators, and private collectors. While Park’s works and those by other Dansaekhwa artists have soared in visibility and price, his practice has continued to evolve. We corresponded as Park approached his 90th birthday in late 2021, before the opening of a new exhibition at Kukje Gallery in Seoul in September, where he was debuting a suite of recent Ecriture paintings, including several in vivid new colors. In February 2022, Park revealed his advanced diagnosis of lung cancer and his decision to not seek treatment. He died from lung cancer on 14 October 2023, at the age of 91.

* Dansaekhwa or Tansaekhwa is a term used to refer to a loose grouping of paintings that originated in Korean painting in the mid-1970s when a group of artists began to push paint, soak canvas, drag pencils, rip paper, and otherwise manipulate the materials of painting. These artists were not involved in the types of pragmatic concerns that were associated with the Minimalist artists. Their focus was on a fundamental approach to painting that involved a specific, cultural reading of nature. Their artworks indirectly resisted the expectations about the forms of art created under an authoritarian regime. The artists also attempted to break away from the heritage of Japanese imperialism and Western abstraction. Dansaekhwa is deeply involved with the physicality of painting. Some of them based their work on traditional Korean ink portraits and used traditional Korean materials such as Hanji paper. The pioneers of Dansaekhwa are: Cho Yong-ik, Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-hwa, Ha Chong-hyun, Hur Hwang, Kim Guiline, Kim Tschang-yeul, Kim Whanki, Kwon Young-woo, Lee Dong-Youb, Lee Ufan, Park Seo-bo, Quac In-sik, Rhee Seundja, Suh Seung-Wong, Youn Myeung-Ro, Yun Hyong-keun.