ART CITIES:Paris-Robert Longo

While Robert Longo has worked in a variety of media (performance, photography, sculpture and painting) he is best known for his large-scale, hyper-realistic charcoal drawings that reflect on the construction of symbols of power and authority. Inspired by Carl Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious, he explores the effects of living in an image-saturated culture – how we filter, retain and process the images that bombard us daily.

While Robert Longo has worked in a variety of media (performance, photography, sculpture and painting) he is best known for his large-scale, hyper-realistic charcoal drawings that reflect on the construction of symbols of power and authority. Inspired by Carl Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious, he explores the effects of living in an image-saturated culture – how we filter, retain and process the images that bombard us daily.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery Archive

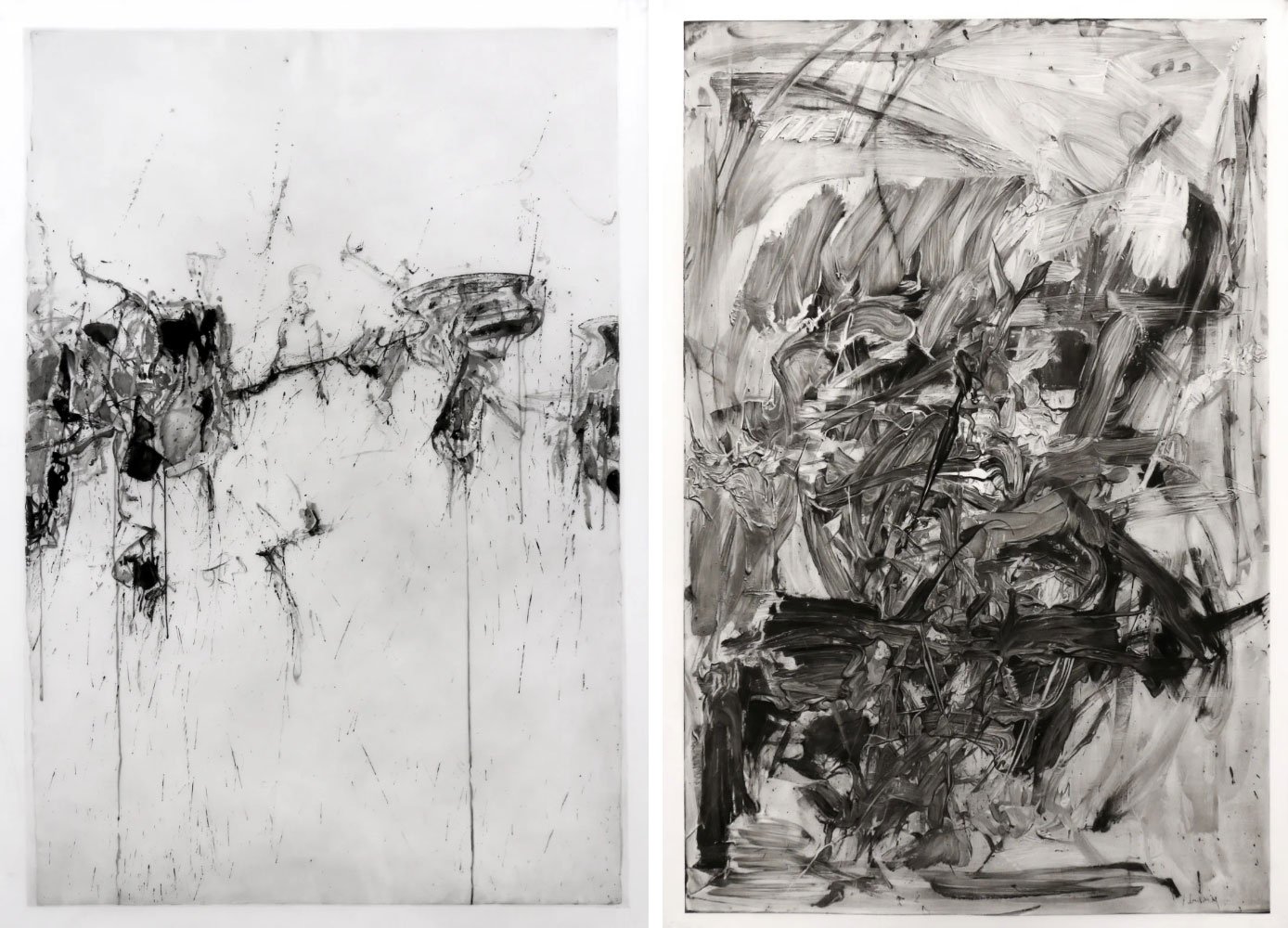

Robert Longo in his solo exhibition “The New Beyond”, presents his most recent series of monumental charcoal drawings paying homage to the European pioneers of post-war art. The exhibition takes its title from “Un art autre”* (1952) by French art critic Michel Tapié, which identifies a new horizon for European Art identifies a new horizon for European Art, heralded by painters such as Jean Fautrier and Jean Dubuffet. Breaking with the traditional codes of painting, these artists produced, in Tapié’s words, ‘”something so extraordinary, endowed with a magic so stupefying, so useless in the dreary framework of the everyday, and at the same time so irreducibly necessary to those who, from day to day, seek to live the parabola of our age”. For Longo, who was born in 1953, this period of artistic revolution is of particular interest, having laid the groundwork for abstraction, as well as new multimedia forms of artistic expression. Following “Gang of Cosmos” his 2014 series of drawings based on American Abstract Expressionism, in this exhibition, Longo explores the work of Karel Appel, Jean Dubuffet, Arshile Gorky, Asger Jorn, Yves Klein, Willem de Kooning, Maria Lassnig, Piero Manzoni, Joan Mitchell, Pierre Soulages, Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) and Zao Wou-Ki. As many of these artists worked in Europe in the years following the Second World War, their experimental and multifarious practices revolutionised art after the trauma of the devastation of war. By revisiting their work in a contemporary context, Longo offers this exhibition as a ‘historical construction’, highlighting the continued influence of these artists, finding a present-day resonance in their ability to transcend through their work the fraught circumstances of a radically changing world. The process of creating a charcoal drawing is almost entirely opposite to the process of creating a traditional painting. Starting with a white page, Longo gradually darkens certain areas to create shadow, ending with the points of deepest black, whereas, in a traditional painting, highlights are applied at the end, over the darker tones. In contrast to the exuberance of a painting such as “Bleu, bleu, le ciel bleu” (1961) by Joan Mitchell, Longo’s approach is measured, even ‘forensic’. But as he studies every brushstroke, carefully recreating their material modulations and nuances of color out of dry, black charcoal, he celebrates the materiality of paint that is, according to de Font-Réaulx, “the sensitive and intimate meaning of these works”. Longo’s drawings are saturated with the time of their making. “All art is a form of political expression” says Longo, who describes himself and all other artists as “the reporters of the time that we live in”. Alongside the drawings of paintings, four smaller charcoal and graphite drawings based on photographs spanning the end of the war to the cultural revolution of 1968 illustrate the context in which the original paintings were produced. They depict the city of Dresden in ruins in 1945 and the mushroom cloud exploding over Nagasaki that same year, as well as Elvis Presley in concert in 1956 and a Soviet tank in Prague in the spring of 1968. It is now widely known that the work of the Abstract Expressionists was appropriated by the American government for its apparent lack of political message and used as propaganda in the form of a travelling exhibition in Europe, whereas the European avant-garde was seen as radical and many of its proponents were rejected by the establishment. As Tapié wrote, ‘art, at that point, can be only a kind of sorcery, of the greatest consequence, inducing us to accept, with full knowledge of what we are doing, the dizzying grandeur of a test of violence beyond considerations of “art criticism”.’ With uncertainty dominating the current political climate in Europe, Longo’s most recent series of drawings encourages us to look to the work of artists whose art helped heal the wounds of war and imagine a different future. As they laid the foundations on which artists still build today, their example might guide a younger generation.

* In December 1952, Michel Tapié publishes a book-manifesto entitle “Un art autre” which accompanied by an exhibition at the Studio Facchetti. Tapié gives pride of place to Georges Mathieu, six of whose canvases are reproduced alongside Pollock, Sam Francis, Dubuffet, Soulages, Hartung, Wols, Michaux, Riopelle, Fautrier, and Appel. The ‘informel’, which Tapié often defines in a convoluted fashion in the lyrical, mystical rhetoric he affects, is supplemented by the less rigid but equally sibylline concept of an ‘art autre’, extended, according to Mathieu, to a “mix of surrealists, expressionists, abstracts, figuratives”.

Photo: Robert Longo, Untitled (After Gorky; Garden in Sochi, 1943), 2022, Charcoal on mounted paper, 160 x 203.2 cm, Photo: Robert Longo Studio. © Robert Longo / Adagp, Paris, 2022

Info: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, 7 Rue Debelleyme, Paris, France, Duration: 17/10-23/12/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://ropac.net/

Right: Robert Longo, Untitled (After de Kooning; Woman/Verso: Untitled, 1948), 2022. Charcoal on mounted paper. Image 213,7 x 177,8 cm (84,13 x 70 in). Photo: Robert Longo Studio. © Robert Longo / Adagp, Paris, 2022

Right: Robert Longo, Study of Big Berg, 2022, Ink and charcoal on vellum, 54.6 x 53.5 cm. Photo: Robert Longo Studio. © Robert Longo / Adagp, Paris, 2022

Right: Robert Longo, Study of After Mitchell; Bleu, bleu, le ciel bleu, 1961, 2021, Ink and charcoal on vellum, 81.8 x 53 cm. Photo: Robert Longo Studio. © Robert Longo / Adagp, Paris, 2022