PRESENTATION: Anni and Josef Albers

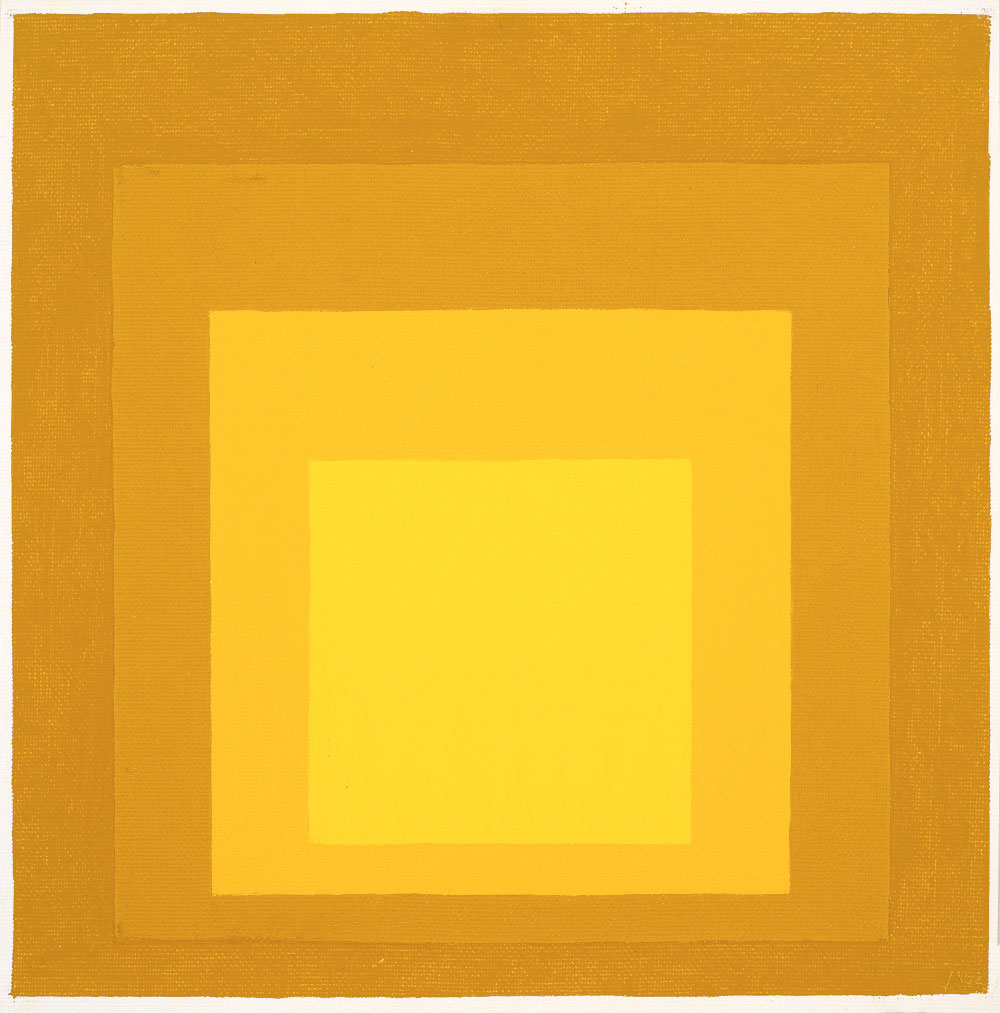

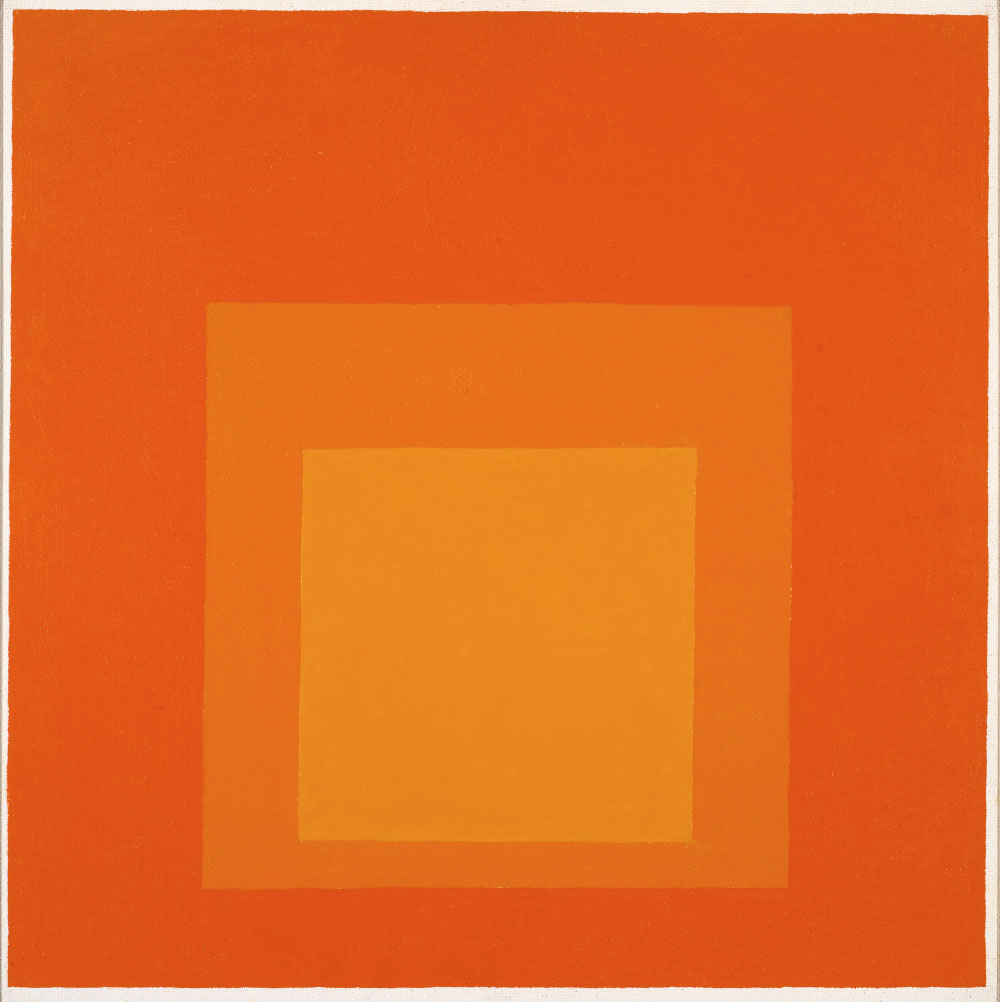

Josef and Anni Albers were among the leading pioneers of twentieth-century modernism. Josef Albers was an influential teacher, writer, painter, and color theorist, best known for the “Homages to the Square” he painted between 1950 and 1976 and for his innovative 1963 publication “Interaction of Color”. Anni Albers was a textile designer, weaver, writer, and printmaker who inspired a reconsideration of fabrics as an art form, both in their functional roles and as wallhangings.

Josef and Anni Albers were among the leading pioneers of twentieth-century modernism. Josef Albers was an influential teacher, writer, painter, and color theorist, best known for the “Homages to the Square” he painted between 1950 and 1976 and for his innovative 1963 publication “Interaction of Color”. Anni Albers was a textile designer, weaver, writer, and printmaker who inspired a reconsideration of fabrics as an art form, both in their functional roles and as wallhangings.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag Archive

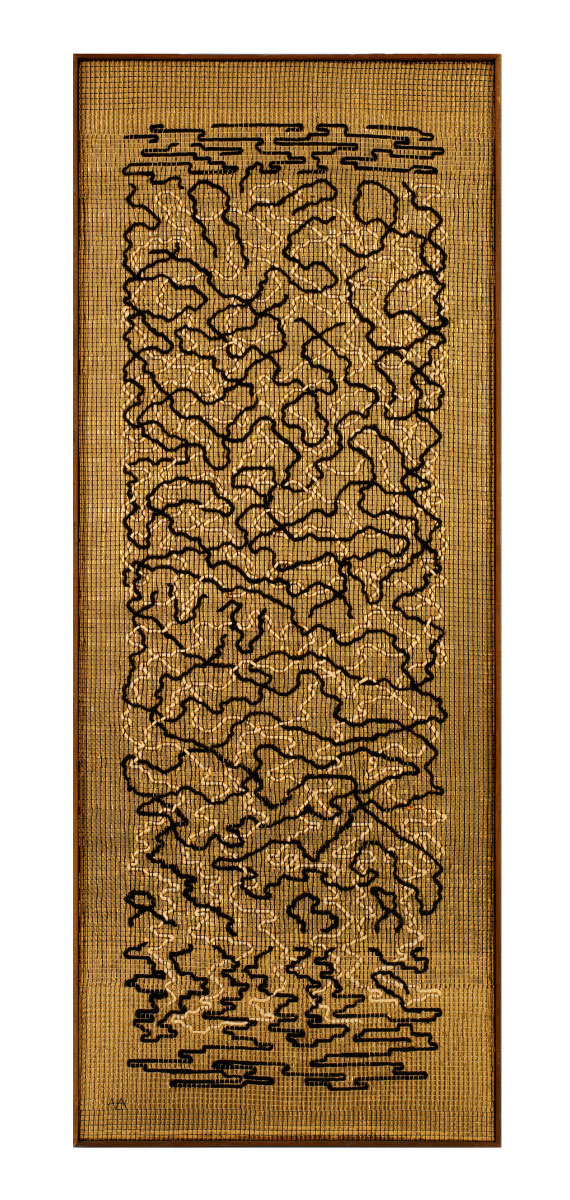

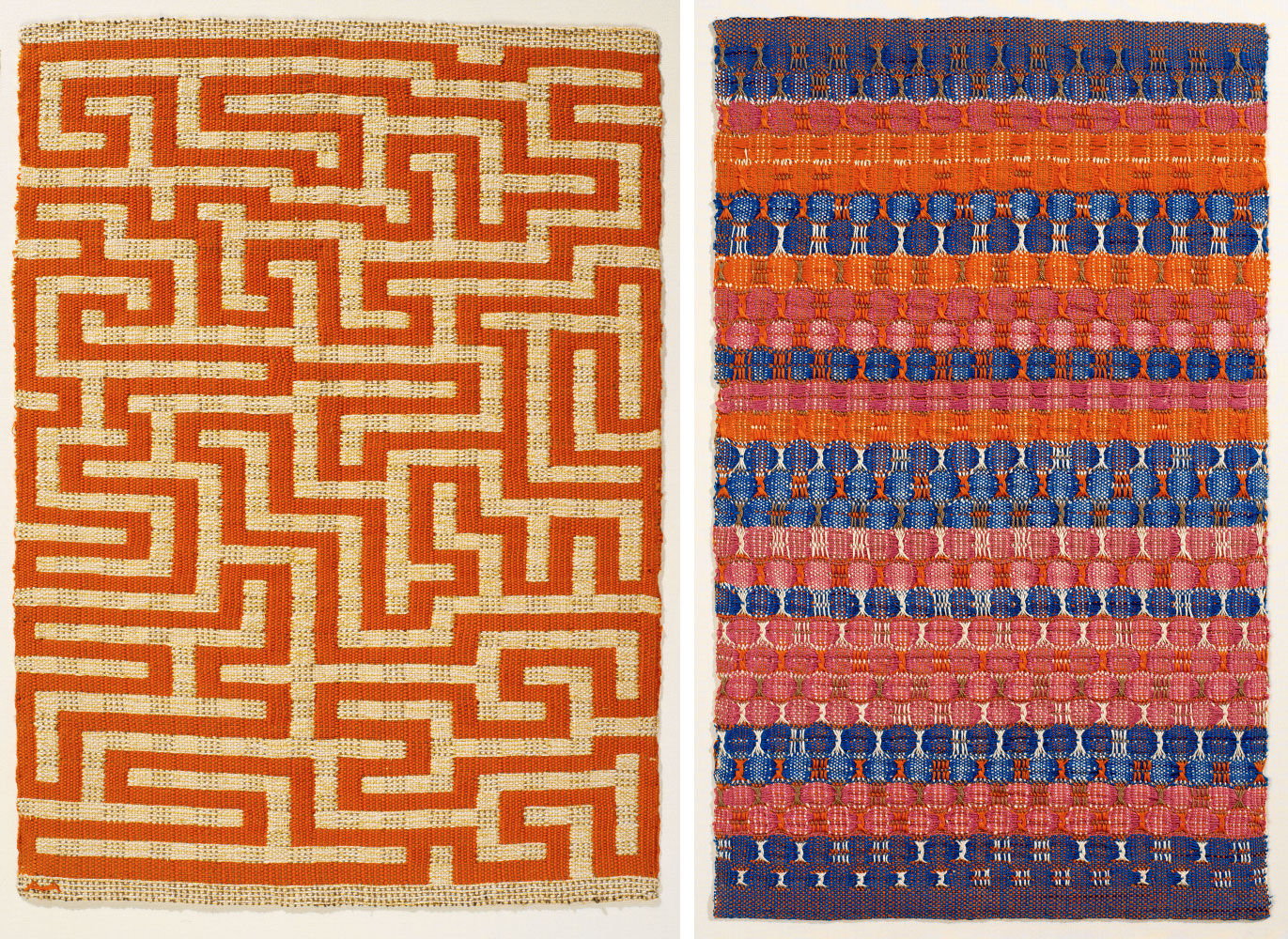

Featuring over 200 artworks (paintings, photographs, furniture, drawings and textile) a retrospective of the work of artistic duo Anni and Josef Albers in presented at Kunstmuseum Den Haag. The exhibition shows how Anni Albers evolved into a true pioneer of modern textile art, and Josef Albers underwent a process of artistic development that culminated in his world-famous Homage to the Square series comprising hundreds of colour studies in a square format. Although Anni and Josef worked with different materials, the exhibition show how much they influenced each other, sharing the same sense of color, rhythm and form that reflects the principles of the Bauhaus – such as respect for the material and for experimentation. The impact of the work and teaching of the Albers on the development of modern art cannot be overstated. Josef and Anni Albers, met in Weimar, Germany in 1922 at the Bauhaus. This new teaching institution, which transformed modern design, had been founded three years earlier, and emphasized the connection between artists, architects, and craftspeople. Before enrolling as a student at the Bauhaus in 1920, Josef had been a school teacher in and near his hometown of Bottrop, in the northwestern industrial Ruhr region of Germany. Initially he taught a general elementary school course; then, following studies in Berlin, he gave art instruction. At the same time, he developed as a figurative artist and printmaker. Once he was at the Bauhaus, he started to make glass assemblages from detritus he found at the Weimar town dump and from stained glass; he then made sandblasted glass constructions and designed large stained-glass windows for houses and buildings. He also designed furniture, household objects, and an alphabet. In 1925, he was the first Bauhaus student to be asked to join the faculty and become a master. At the end of the decade he made exceptional photographs and photo-collages, documenting Bauhaus life with flair. By 1933, when pressure from the Nazis forced the school to shut its doors, Josef Albers had become one of its best-known artists and teachers, and was among those who decided to close the school rather than comply with the Third Reich and reopen adhering to its rules and regulations. Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann went to the Bauhaus as a young student in 1922. Throughout her childhood in Berlin, she had been fascinated by the visual world, and her parents had encouraged her to study drawing and painting. Having been brought up in an affluent household where she was expected simply to continue living the sort of comfortable domestic life enjoyed by her mother, she rebelled by deciding to be an artist and going off to an art school that embraced modernism and where the living conditions were rugged and the challenges immense. She entered the weaving workshop because it was the only one open to her, but soon embraced the possibilities of textiles. She and Josef, eleven years apart in age, met shortly after her arrival in Weimar. They were married in Berlin in 1925—and Annelise Fleischmann became Anni Albers. At the Bauhaus, Anni experimented with new materials for weaving and became a bold abstract artist. She used straight lines and solid colors to make works on paper and wall hangings devoid of representation. In her functional textiles she experimented with metallic thread and horsehair as well as traditional yarns, and utilized the raw materials and components of structure as the source of design and beauty. In 1925 the Bauhaus moved to the city of Dessau to a streamlined and revolutionary building designed by Walter Gropius, the architect who had founded the school. The Alberses, who had become friends with Paul and Lily Klee, Wassily and Nina Kandinsky, Oscar and Tut Schlemmer and Lyonel and Julia Feininger, eventually moved into one of the masters’ houses designed by Gropius.

After the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close in 1933, the architect Philip Johnson, then a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Josef and Anni Albers were invited to the USA when Josef was asked to make the visual arts the center of the curriculum at the newly established Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Black Mountain College was a liberal arts college with an innovative and progressive curriculum that repositioned the study and practice of art from the margin to the center of the undergraduate program, and Albers’s preliminary art course in materials and form was one of only two courses required of all students, regardless of major. Although Black Mountain’s focus was not the training of professional artists, the emphasis placed on the centrality of art to everyday life, and its integrative and collaborative approach to art-making, attracted creative students and faculty in every media, from painting and literature to dance and architecture. Albers brought the theories and teaching methods of the Bauhaus to Black Mountain, but he was influenced in turn by the progressive educational philosophy of American philosopher John Dewey, with its emphasis on experimentation and direct experience as central to the learning experience. They remained at Black Mountain until 1949, while Josef continued his exploration of a range of printmaking techniques, took off as an abstract painter, made collages of autumn leaves, kept writing, became an ever more influential teacher and wrote about art and education. Anni made extraordinary weavings, developed new textiles, and taught, while also writing essays on design that reflected her independent and passionate vision. Meanwhile, the Alberses began making frequent trips to Mexico, a country that captivated their imagination and had a strong effect on both of their art. They often said that, “In Mexico, art is everywhere”: this was their ideal for human life. In 1950, the Alberses moved to Connecticut. From 1950 to 1958, Josef Albers was chairman of the Department of Design at the Yale University School of Art. There, and as guest teacher at art schools throughout North and South America and in Europe, he trained a whole new generation of art teachers. He also continued to write, paint, and make prints. In 1971, he was the first living artist ever to be honored with a solo retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time of his death in New Haven, Connecticut in 1976, he was still working on his “Homages to the Square” and his “Structural Constellations”, deceptively simple compositions in which straight lines create illusory forms, and which became the basis of prints, drawings, and large wall reliefs on public buildings all over the world. In those same years, Anni Albers continued to weave, design, and write. In 1963 she began to explore printmaking, and experimented with the medium in unprecedented ways while developing further as a highly original abstract artist. Her seminal text “On Weaving” was published in 1965.

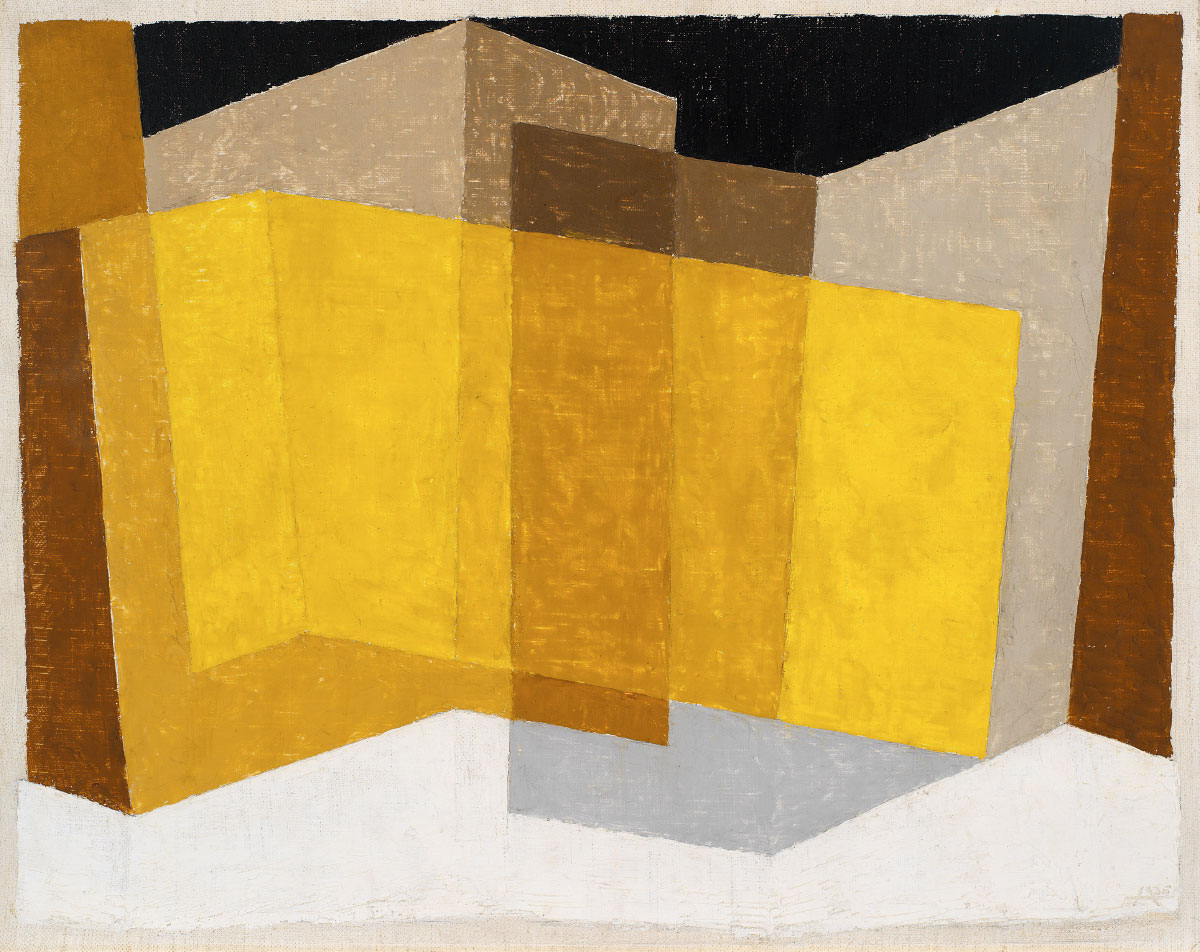

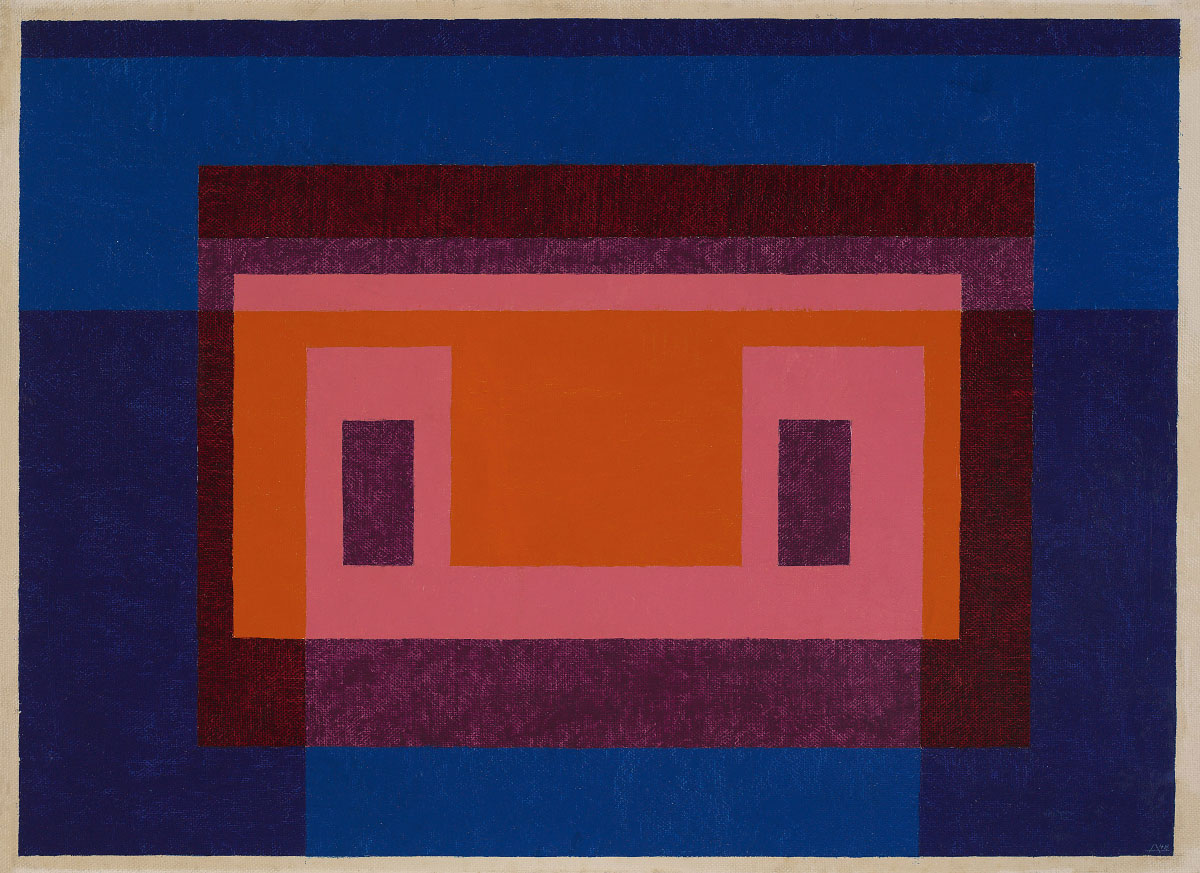

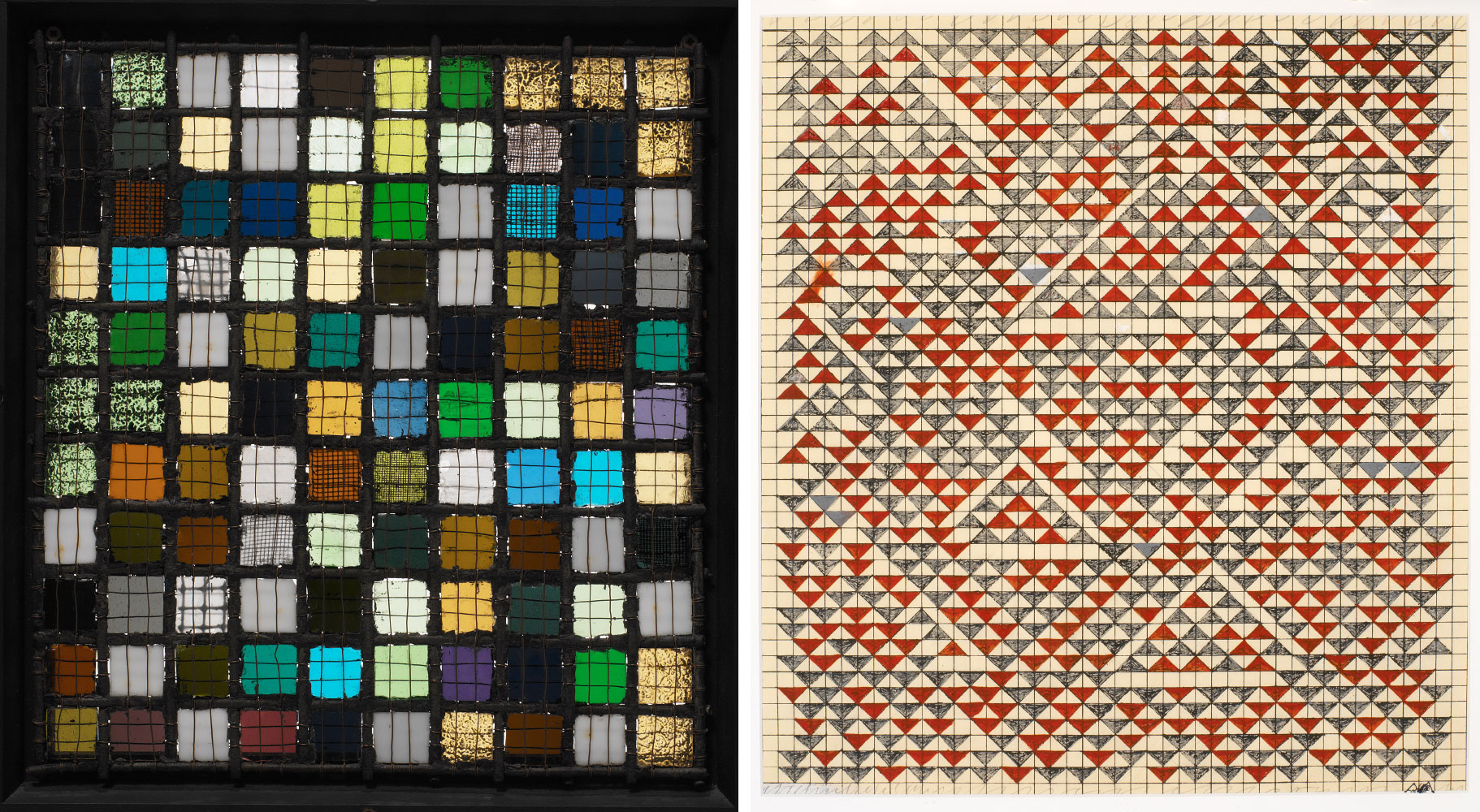

Photo: Josef Albers, Variant/Adobe: 4 Central Warm Colors Surrounded by 2 Blues, 1948, Oil on Masonite 66 x 90,8 cm, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

Info: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Stadhouderslaan 41, Den Haag, The Netherlands, Duration: 15/10/2022-15/1/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00, www.kunstmuseum.nl/

Right: Anni Albers, Study for Camino Real, 1967, Gouache and diazotype on paper, 17 1/2 x 16 in. (44.5 x 40.6 cm), The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Right: Anni Albers, Red and Blue Layers, 1954 ,Cotton, 24 1/4 x 14 7/8 in. (61.6 x 37.8 cm), The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation