TRIBUTE: Territories of Waste-On the Return of the Repressed, Part II

The exhibition “Territories of Waste On the Return of the Repressed” shows various engagements with waste as the repressed remains of our civilization. The artists whose works are exhibited here share the desire to visualize the global and ecological consequences of our consumption. The twenty-five artistic perspectives presented address those impacts of our production of goods and waste that are normally hidden from view (Part I).

The exhibition “Territories of Waste On the Return of the Repressed” shows various engagements with waste as the repressed remains of our civilization. The artists whose works are exhibited here share the desire to visualize the global and ecological consequences of our consumption. The twenty-five artistic perspectives presented address those impacts of our production of goods and waste that are normally hidden from view (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Museum Tinguely Archive

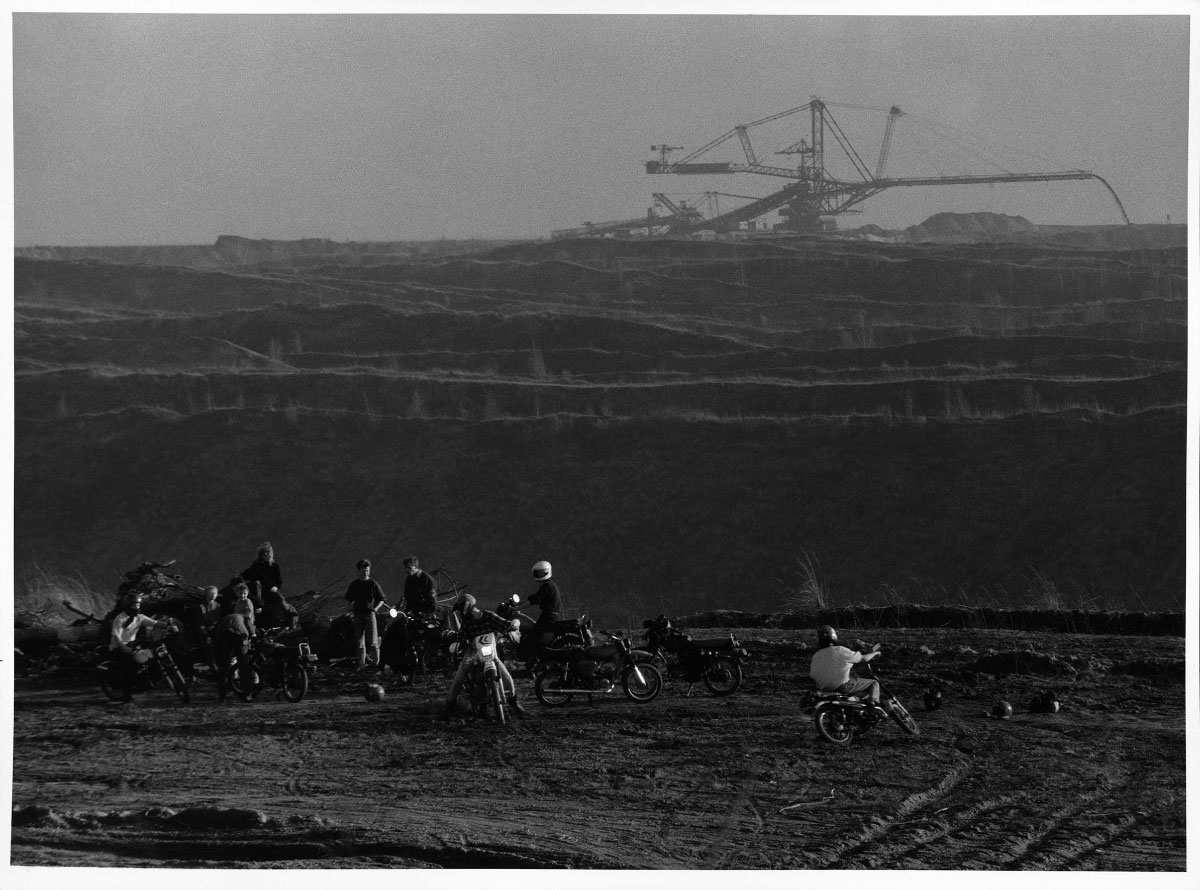

The starting point of “Territories of Waste On the Return of the Repressed” is the present, as exemplified by installations, videos, sculptures, photographs, and performances, while a selection of historical works proves that pollution and the environmental devastation caused by the extraction of raw materials was a concern of artists even in the 1960s. Jean Tinguely also produced works that critique consumer society. It was these that prompted Museum Tinguely to embark on a show that would tackle what is left behind, i.e. waste, from today’s geopolitical perspective. The works exhibited bring to the fore what most of us repress. They show scarred landscapes and through images and stories provide palpable reminders of how inextricably bound up with the Earth itself and all its many life forms we are. Not only do they convey a knowledge of how connected all human activities are, but they also contain within them the power to open our minds. The preoccupation with garbage intensified after the Second World War, when the concept of planned obsolescence first arose and ecology slowly came to our attention as a matter of concern to us all. The zoologist Rachel Carson wrote about the steady spread of pollutant pesticides, while the growing mounds of refuse became emblematic of affluent Western society itself – that is, conspicuous superabundance. Yet our production of refuse did not decline. On the contrary, Switzerland produced 700 kilos of garbage per capita in 2020, which is one of the highest rates in the world. Sophisticated waste management may have made that waste less visible, at least in Europe and North America, but heavy metals, dust particles, and microplastics have long since reached every inch of the global ecosphere. The same period has also seen a shift in how society engages with the subject of waste. Like all things repressed, it has inevitably bounced back. After all, garbage never really disappears; it is simply recirculated, as the biologist Lynn Margulis has pointed out. Whereas refuse used to be treated as a local problem requiring a technical solution, our focus now is on the global threat posed by pollution and environment devastation. The ever more widespread use of the English term waste reflects this new perspective on residues as waste. Reflection on the theme of waste is not only a subject of contemporary art, but it is actually prompted and influenced by it. The artists presented in the exhibition in Basel inquire into the hidden and repressed ecological consequences of our habits of consumption and render these visible: Pinar Yoldas, for example, presents a work that shows what life forms emerging from oceans full of microplastics might look like. Tita Salina & Irwan Ahmett are rather less given to science fiction and in their video show how the rivers of Jakarta are contaminated and clogged with plastics.

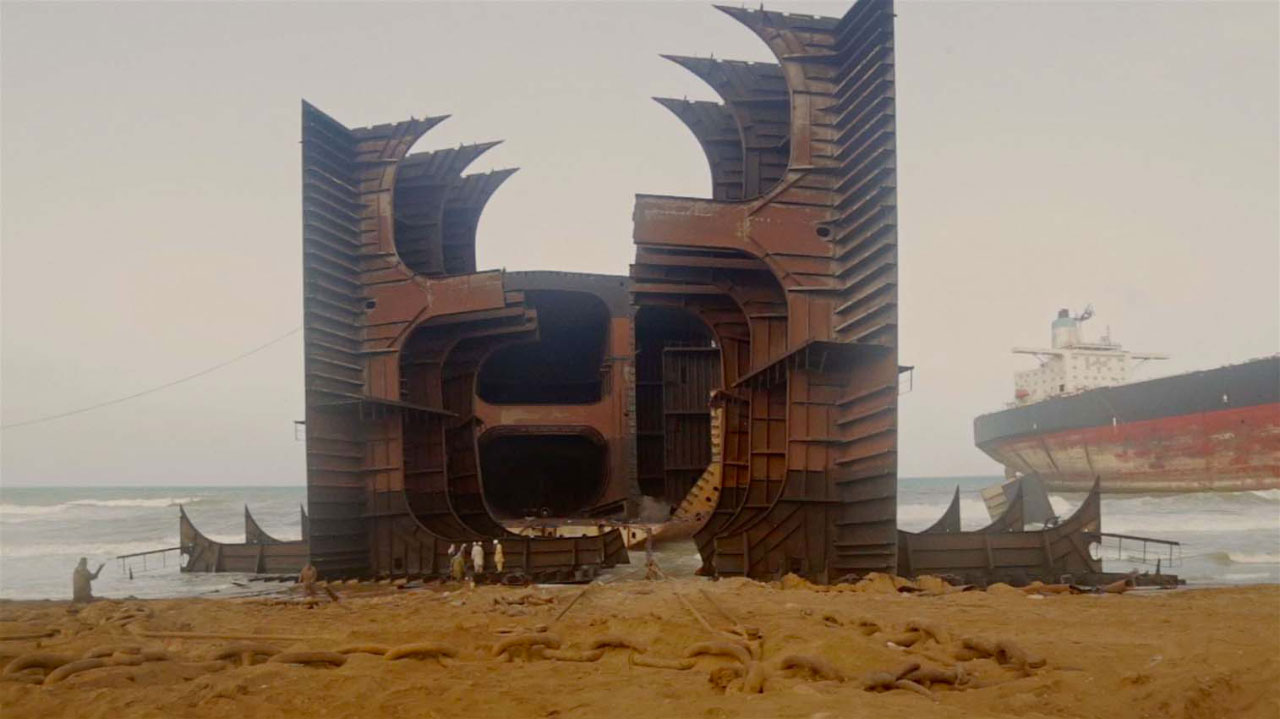

Anca Benera & Arnold Estefan for their part collected sand samples from the Normandy beaches where the Allies landed in the summer of 1944, revealing that the sand there still contains heavy metals. Julien Creuzet’s installation consisting of intricate sculptures and a film in the style of a music video reflects the pollution of the French Antilles with pesticides. What makes waste invisible, however, is not just its microscopic size. These days garbage is shunted all over the world along (neo-)colonial trade routes. This is evident from Hira Nabi’s film about freighters being broken up for scrap on the coast of Pakistan. Landscapes ravaged by mining and mineral extraction are also at the heart of today’s artistic practices. Otobong Nkanga, for example, presents her research findings on a copper mine in Tsumeb, Namibia, in an installation composed of objects, images, and video. In doing so she recalls the places that were exploited – by German colonialists, among others – for the purpose of gaining access to natural resources. Indeed, most of the wrecked landscapes and wastelands are in the Global South – far beyond our field of vision – even if they are connected to Europe by our import of consumer goods and export of waste. The exhibition positions these contemporary works in dialogue with several iconic works of the past. In 1981, for example, the Argentinian artist and environmental activist Nicolas Garcia Uriburu, dyed the Rhine at Dusseldorf green – the Rhine in those days being one of the most heavily polluted rivers in Europe. He and Joseph Beuys (who joined him for this action) even filled the green water in bottles to sell in an edition. On the other side of the Atlantic, the performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles had previously addressed the work that went into keeping a home, a museum, or a big city clean by creating works of what she defined as Maintenance Art. Museum work itself is also a factor when the subject is waste, as Eric Hattan’s exhibit shows. Using discarded exhibition architecture collected since the beginning of this year, this Swiss artist built a temporary installation in the center of the exhibition space. It is a work that prompts us to think critically about the use of resources in exhibition – making, too. Hattan’s humorous handling of materials from the world of art in combination with everyday objects is reminiscent of the works of Jean Tinguely. The exhibition is conceived as a landscape in which the contemporary and historical works along with works that we commissioned generate a polyphonic sound without forcing the audience to follow a preconceived, didactic path.

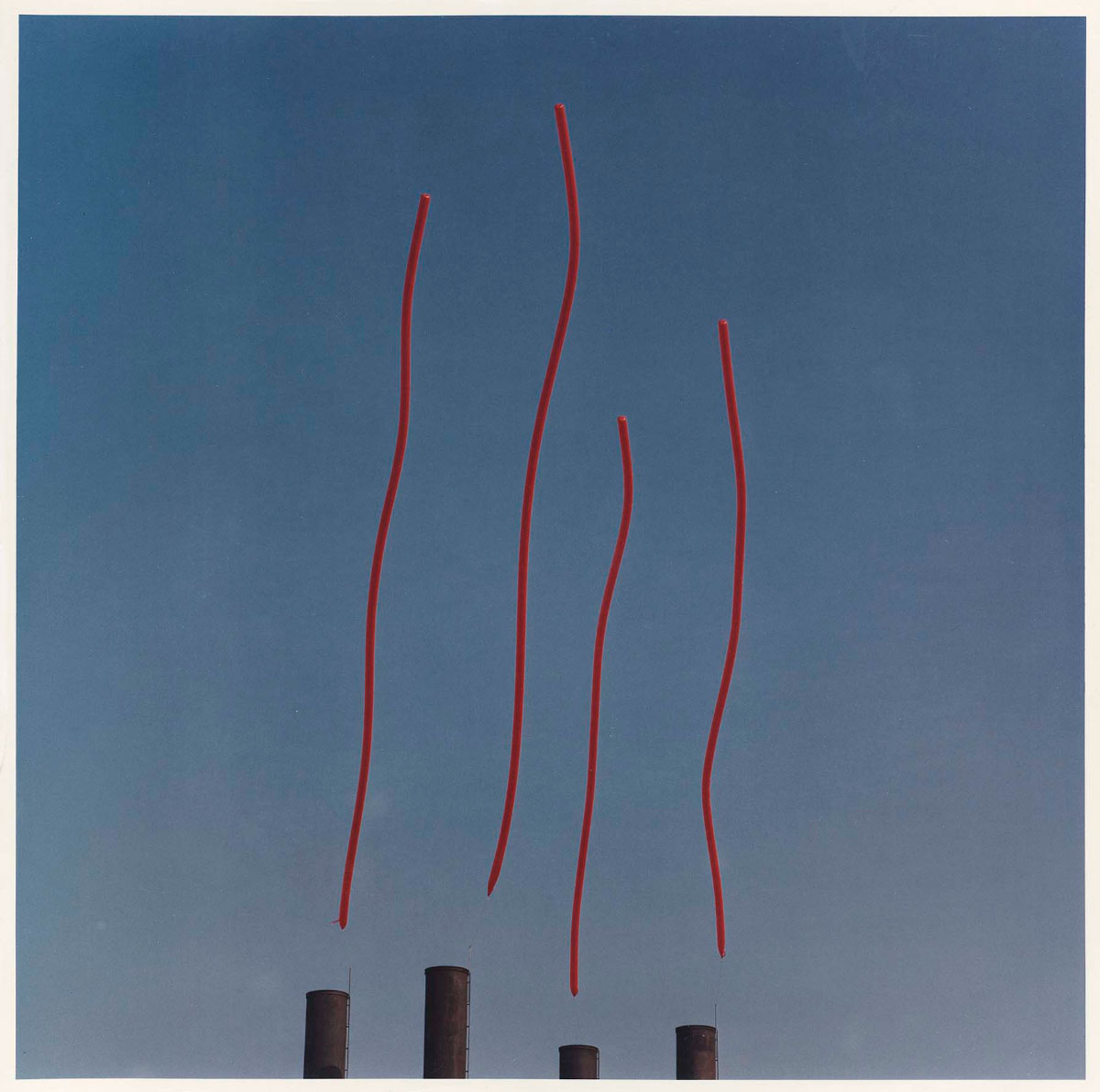

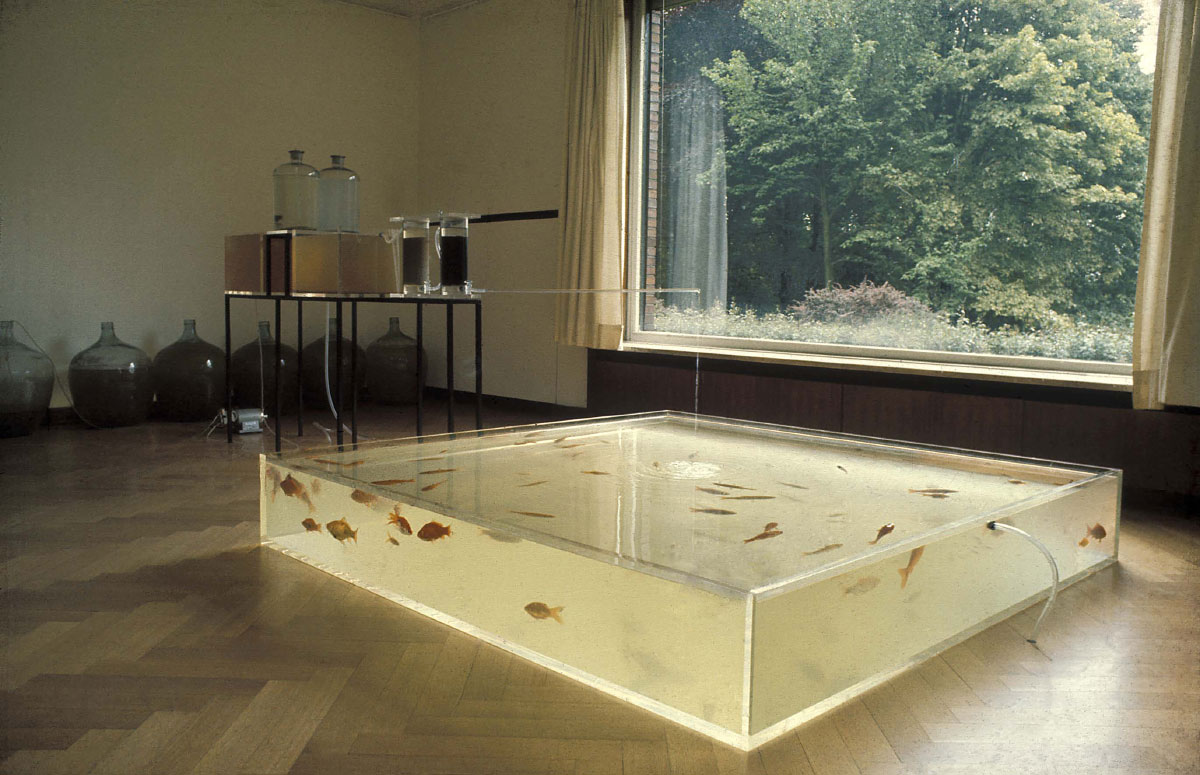

Works by: Arman, Helene Aylon, Lothar Baumgarten, Anca Benera & Arnold Estefan, Joseph Beuys, Rudy Burckhardt, Carolina Caycedo, Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Julien Creuzet, Agnes Denes, Douglas Dunn, Julian Aaron Flavin, Nicolas Garcia Uriburu Hans Haacke, Eric Hattan, Eloise Hawser, Fabienne Hess, Barbara Klemm, Max Leifs, Diana Lelonek, Jean-Pierre Mirouze, Hira Nabi, Otobong Nkanga, Otto Piene, realities:united, Romy Ruegger, Ed Ruscha, Tita Salina & Irwan Ahmett, Tejal Shah, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Raul Walch, Pinar Yoldas

Photo: Hira Nabi, All That Perishes at the Edge of Land (film still), 2019, Film, colour, sound, 30 min. Courtesy the artist, © Hira Nabi

Info: Curator: Dr. Sandra Beate Reimann, Museum Tinguely, Paul Sacher-Anlage 1, Basel, Switzerland, Duration: 14/9/2022-8/1/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 11:00-18:00, Thu 11:00-21:00, https://www.tinguely.ch

Right: Fabienne Hess, Madame X, 2016, Digital print on silk; 170 × 125 cm; edition of 6 Collection the artist, © Fabienne Hess; photo: Fabienne Hess