ART CITIES: Tokyo-Kenjirō Okazaki

Kenjirō Okazaki has developed a wide range of interdisciplinary practices that transcend conventional artistic genres and classifications of art, including architecture, literary theory, painting, relief, sculpture, robotics, and contemporary dance. Carrying on the investigations of Sophie Taeuber Arp, Paul Klee, Tomoyoshi Murayama, Saburo Hasegawa, and John Cage, at the root of Okazaki’s thinking is the exploration and reconstruction of time and space at the foundation of human perception.

Kenjirō Okazaki has developed a wide range of interdisciplinary practices that transcend conventional artistic genres and classifications of art, including architecture, literary theory, painting, relief, sculpture, robotics, and contemporary dance. Carrying on the investigations of Sophie Taeuber Arp, Paul Klee, Tomoyoshi Murayama, Saburo Hasegawa, and John Cage, at the root of Okazaki’s thinking is the exploration and reconstruction of time and space at the foundation of human perception.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Blum & Poe Gallery Archive

In October of 2021, Kenjirō Okazaki suffered a severe stroke. After more than six months of hospitalization and rrehabilitation, his body and mind made a remarkable recovery, allowing him to resume painting—something that was predicted to be impossible early on in his convalescence. This experience led Okazaki to rediscover the relationship between the body, the mind, and the world. It also gave him a new perspective on the significance of artistic creation. His solo exhibition “TOPICA PICTUS Revisited: Forty Red, White, And Blue Shoestrings And A Thousand Telephones” is the first displaying new work by the artist since his discharge from the hospital. “TOPICA PICTUS” takes its name, firstly, from topos, a rhetorical device that Aristotle deployed to describe a source or place from which a speaker may locate their argument. Secondly, the name is taken from the Latin word pictus, which means “painted.” Okazaki uses his small-scale, abstract paintings as the containing factor, a topos, to loosely suggest his influences and present them alongside one another. In TOPICA PICTUS Revisited: Forty Red, White, And Blue Shoestrings And A Thousand Telephones, the artist unites under a topos his encounter with becoming defamiliarized from his physicality—recorded and presented here through the act of painting—with references in the works’ titles to concepts such as Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited,” Polish folklore, or 黙示 , the Japanese word for “revelation.”

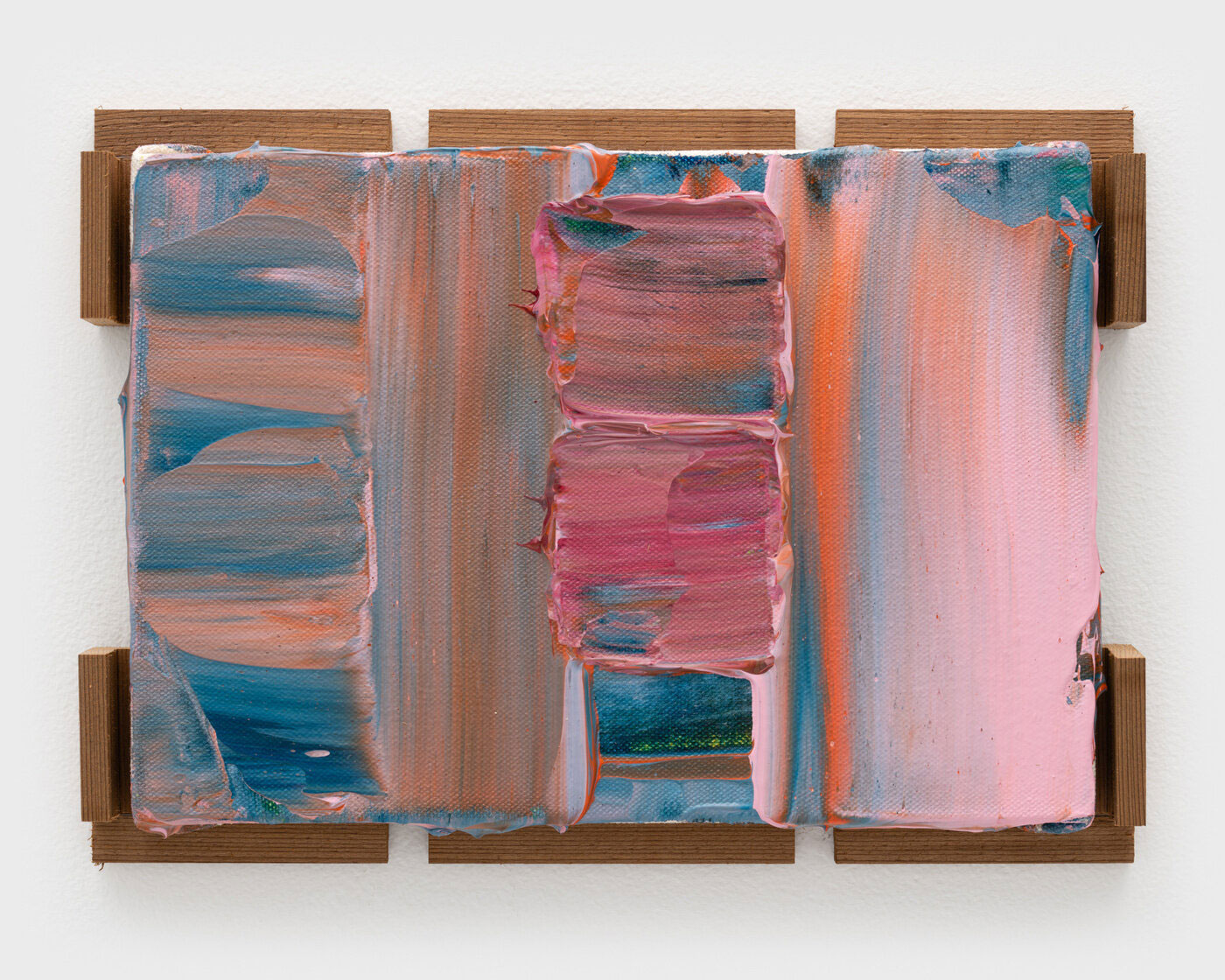

Over the past three decades, Kenjirō Okazaki has been developing a unique series of paintings that expands the vocabulary of these abstract passages. For example, in his early diptychs, abstract fragments are read as gestural motifs, generating sequences (or sentences, in literary terms) with temporal (and spatial) disruptions as in music and dance. By organizing near identical gestures, or motifs, in these works, one can say they are careful lessons in observation that challenge the limits of our perception. By looking back and forth between two canvases, a new emergence from our visual perception arises. One is forced to experience a sudden reflection. The fragments that repeat on each canvas like a single word or afterimage generate a different context each time, reminding us of something else. The memories generated by his paintings extend from his own daily life to all of human history as well as art history, nature, and the universe. Like a drop of ink in water, the memories are a chain of indexes occurring one after the other—this unfolding appears as a unique event each time a new viewer encounters a painting. Therefore, each painting can always be singular. Okazaki’s painterly passages are specifically manifested by a tactile paint, the mixing of acrylic paints that reflect light within and onto the canvases through a wet, gel-like transparency and the thick textural application of pastel pigments. The sequence that emerges from these tactile indexes is also reflected in his titles, which are written as long paragraphs. The title is no longer a title but an independent series or work in itself. This interplay between painting, memory, and place is explored in his intimately scaled painting series, Zero Thumbnail, and more recently, TOPICA PICTUS. Developed out of our shared isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, each abstract painting in TOPICA PICTUS is accompanied by a short essay and reference image that represents the artist’s journey through the history of painting and objects that allow for interactive encounters that continue to generate between these three bodies: painting, text, and reference. Since his artistic debut forty years ago, Okazaki has also been well-known for his relief works, a series of geometric fragments (akin to small axonometric structures) installed in relation to the surrounding architectural space. The reliefs and spatial expression between them when installed together transcends the actual work themselves. Just as the natural light alters the mood of the installation throughout the day, each series—which possess titles of specific places in Tokyo as well as abstract numbers—triggers an individual’s spatiotemporal perceptions of concrete memories and places, and impressions derived from the palette. These spaces, formed by the geometrical structures between each of the reliefs, thus conjure immeasurable, allegorical spaces of memory.

Photo Left: Kenjirō Okazaki, Haunted Pagan Vegan / やさいのおばけ / Cabbage Beggar, 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 9 7/8 x 7 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches framed, Photo: SAIKI, © Kenjirō Okazaki, Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe Gallery. Right: Kenjirō Okazaki, Sar-i Sang Mines / 東方浄瑠璃 (Eastern Pure Lapis Lazuli) / oṃ huru huru caṇḍāli mātaṅgi svāhā, 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 9 7/8 x 7 1/2 x 1 1/8 inches framed, Photo: SAIKI, © Kenjirō Okazaki, Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe

Info: Blum & Poe Gallery, Harajuku Jingu-no-mori 5F, 1-14-34 Jingumae, Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan, Duration: 26/9-6/11/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 12:00-18:00, www.blumandpoe.com/

Right: Kenjirō Okazaki, Announcement to Mac the Finger / How Can This Be since I Do Not Know Myself Physically? / 黙示, 2022, Acrylic on canvas, 9 7/8 x 7 1/4 x 1 1/8 inches framed, Photo: SAIKI, © Kenjirō Okazaki, Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe