ART CITIES: N.York-Beatriz Milhazes

Beatriz Milhazes’s work bursts with a chromatic and freeing vitality. Renowned for her visual language rooted in painting, collage, and printmaking, she draws on her native Rio de Janeiro. Her use of color and geometry is mined from the botanical gardens and the Tijuca forest near her studio, the surrounding city, its ocean front, and the cultural motifs of Brazil—and from memory.

Beatriz Milhazes’s work bursts with a chromatic and freeing vitality. Renowned for her visual language rooted in painting, collage, and printmaking, she draws on her native Rio de Janeiro. Her use of color and geometry is mined from the botanical gardens and the Tijuca forest near her studio, the surrounding city, its ocean front, and the cultural motifs of Brazil—and from memory.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Pace Gallery Archive

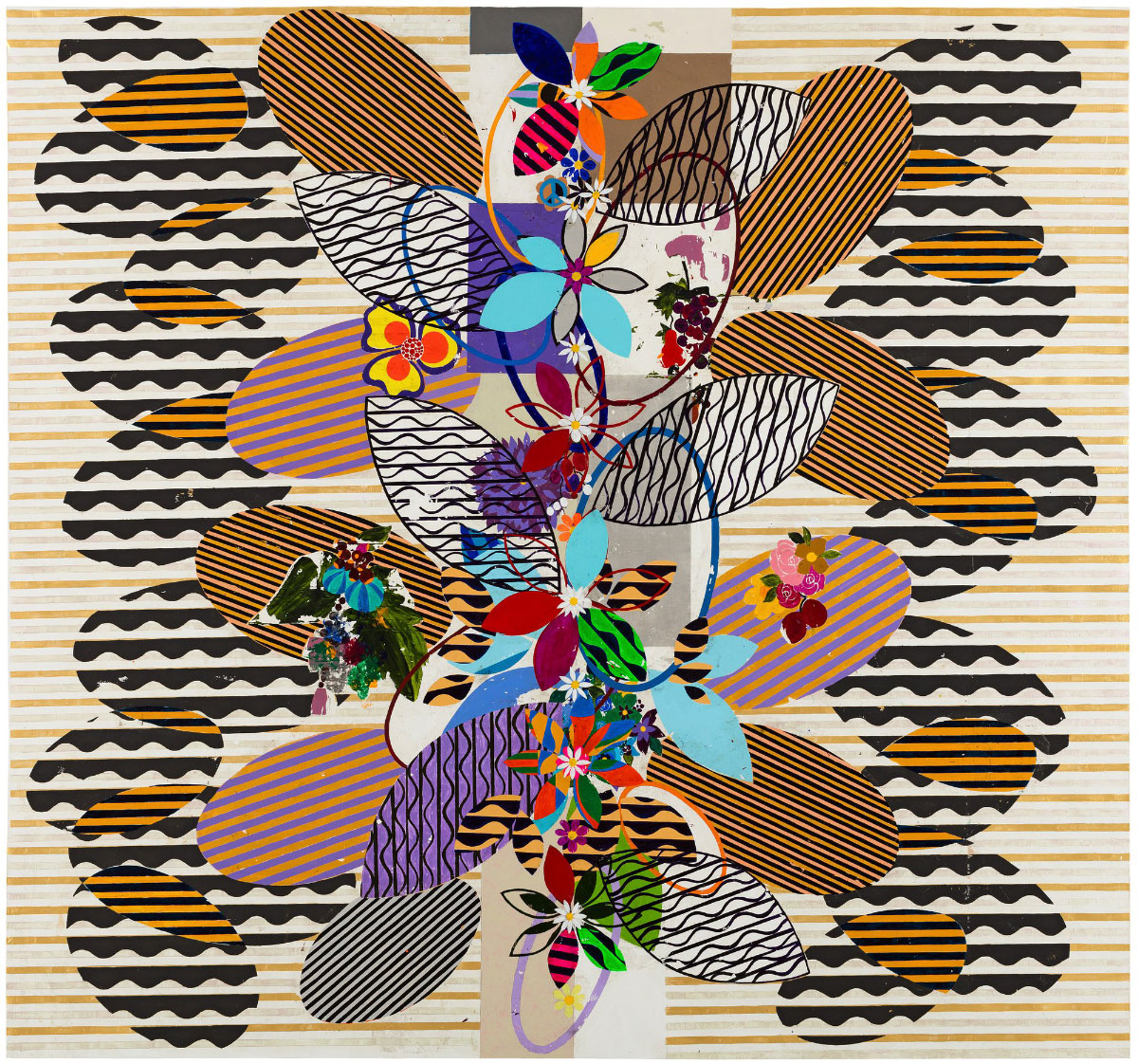

Beatriz Milhazes in her solo exhibition “Mistura Sagrada” presents ten vibrant, large-scale paintings created in 2021 and 2022, as well as a large-scale mobile sculpture. The works in the exhibition exemplify Milhazes’s uncanny ability to forge dynamic, unified choreographies with seemingly disparate elements, patterns, and hues. The layered compositions resulting from these formal investigations possess a kinetic quality, unfolding and reforming over time. The presentation marks Milhazes’s first solo exhibition with Pace since she joined the gallery in 2020 and her first show in New York in nearly a decade. Pace Publishing will produce a catalogue on the occasion of the exhibition. Drawing inspiration from European Modernism, Baroque decorative arts, the Brazilian Antropofagia* movement, and other art historical sources, Milhazes is known for conjuring energetic plays of color and form in her paintings, collages, prints, and installations. Her use of color and geometry is mined from place—the botanical gardens and the Tijuca forest near her studio, the surrounding city of Rio de Janeiro, its ocean front, and the cultural motifs of Brazil—and memory. This process culminates in the artist’s patented form of abstraction, which she has termed “chromatic free geometry”. The paintings which range from five to over nine feet wide, consolidate her return to figuration, which she resumed in 2017. The artist has filled the works in the show with imagery of the natural world, from flowers, trees, and totems to suns and stars. Notably, the titles of these poetic works directly reference their contents, drawing viewers into magical, generative, natural worlds. Milhazes created the works in of the exhibition during the period of quarantine caused by the pandemic, which deeply impacted her painting process and her approach to art making. Without access to travel, gatherings, or most of the usual stimulations of modern life, the artist imbued her new works with a mood of contemplation that she experienced during a period of social isolation and uncertainty. Meditating on complex systems, circuits, and concepts, the artist produced works that are engaged with celestial phenomena and geometries found in nature. The compositions in Mistura Sagrada reflect a sacred mixture of nature, humanity, and spirituality that Milhazes brought to the fore of her practice during the pandemic. Her sculpture “Gamboa III” (2020) is hung from the ceiling of the exhibition space. “Gamboa III” incorporates various materials inspired by Carnival props, in part reused, including adornments made from acrylic on foam board, textile, plastic, and plexiglass. With its dizzying constellations of flowers and madcap forms, the intricate work, which is anchored by an iron structure, produces mesmeric, immersive effects. Featuring allusions to Brazilian popular culture and folk traditions—including the political implications of the celebration of Carnival in Brazil—as well as the country’s Tropicália and Bossa Nova musical movements of the late 1960s, “Gamboa III” follows “Gamboa II” (2016), a hanging sculpture displayed for four months in the lobby of the Jewish Museum in New York in 2016. The artist created her first “Gamboa” installation in 2008 after her work designing sets for her sister’s contemporary dance company. “It’s a three-dimensional relationship with the motifs and elements that I use,” Milhazes said of Gamboa II in a 2020 interview. “It’s like they were animated.”

* Meaning cannibalism, anthropophagia as an art term is associated with the 1960s Brazilian art movement Tropicália whose work, although being culturally and politically rooted in Brazil, took influences from Europe and America. Embracing the writings of the poet Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954), who wrote the “Manifesto Antropófago” (Cannibal Manifesto) in 1928, they argued that Brazil’s history of cannibalising other cultures was its greatest strength and had been the nation’s way of asserting independence over European colonial culture. The term also alluded to cannibalism as a tribal rite that was once practised in Brazil. The artworks made as a result of this concept stole their influences from Europe and America but, ultimately, were rooted in the cultural and political world of 1960s and 1970s Brazil.

Photo: Beatriz Milhazes, Pó de arroz, 2017/2018, Acrylic on linen, 110 ¼ x 139 in., Photo Manuel Águas & Pepe Schettino, © Beatriz Milhazes, Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery

Info: Pace Gallery. 540 West 25th Street, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 16/9-29/10/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.pacegallery.com/

Right: Beatriz Milhazes, Bala de leite em roxo e azul ultramar, 2017, 140 cm x 100 cm, Photo: Pepe Schettino, © Beatriz Milhazes, Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery