ART CITIES: Los Angeles-Ha Chong Hyun

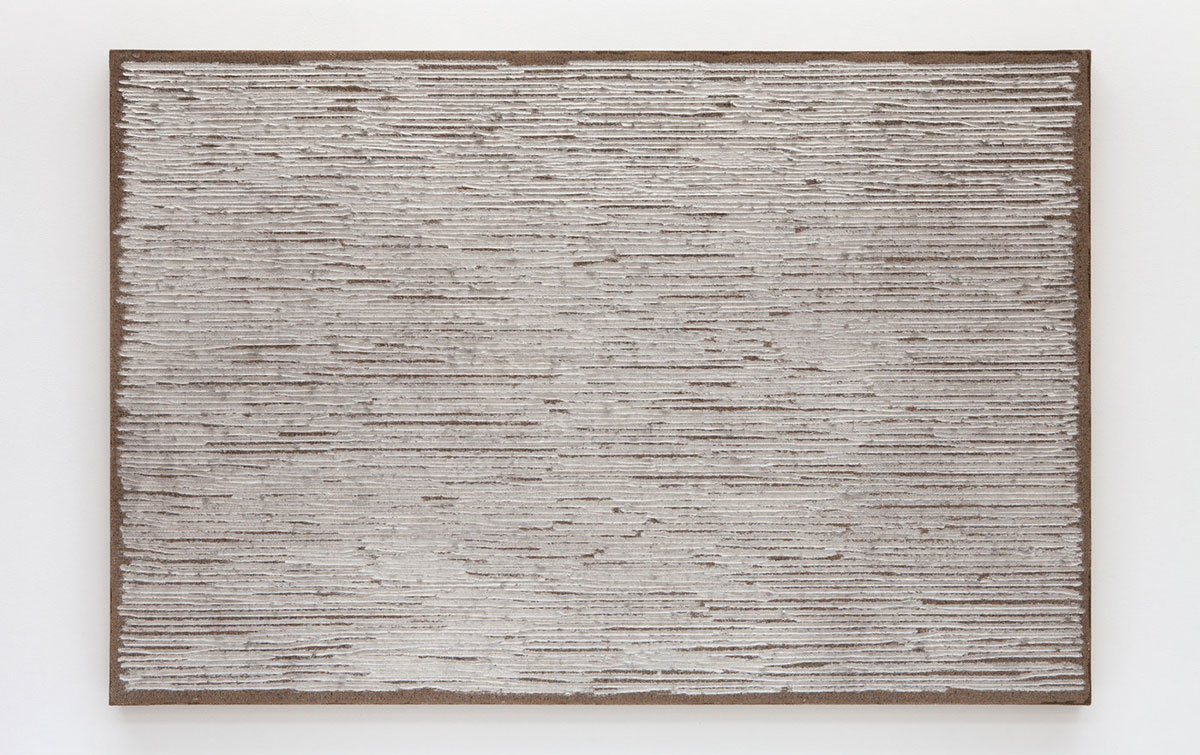

Ha Chong-Hyun came to prominence with his “Conjunction” series in the early 1970s. These early experiments have led him to build his signature style, pushing the paint from the back to the front of hemp cloth. As a leading member of Dansaekhwa, he has consistently used material experimentation and innovative studio processes to redefine the role of painting, playing a significant role bridging the avant-garde traditions between East and West.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Blum & Poe Gallery Archive

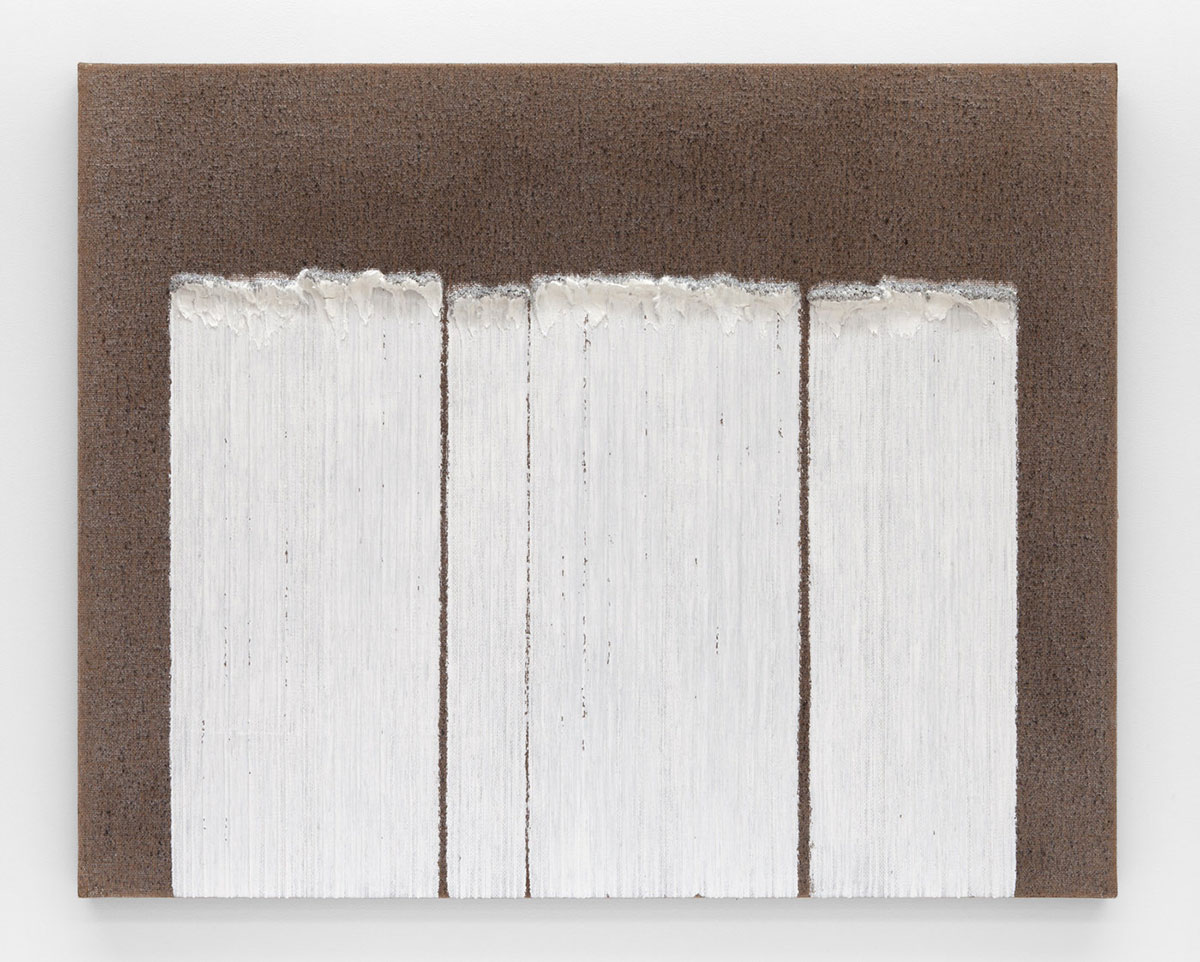

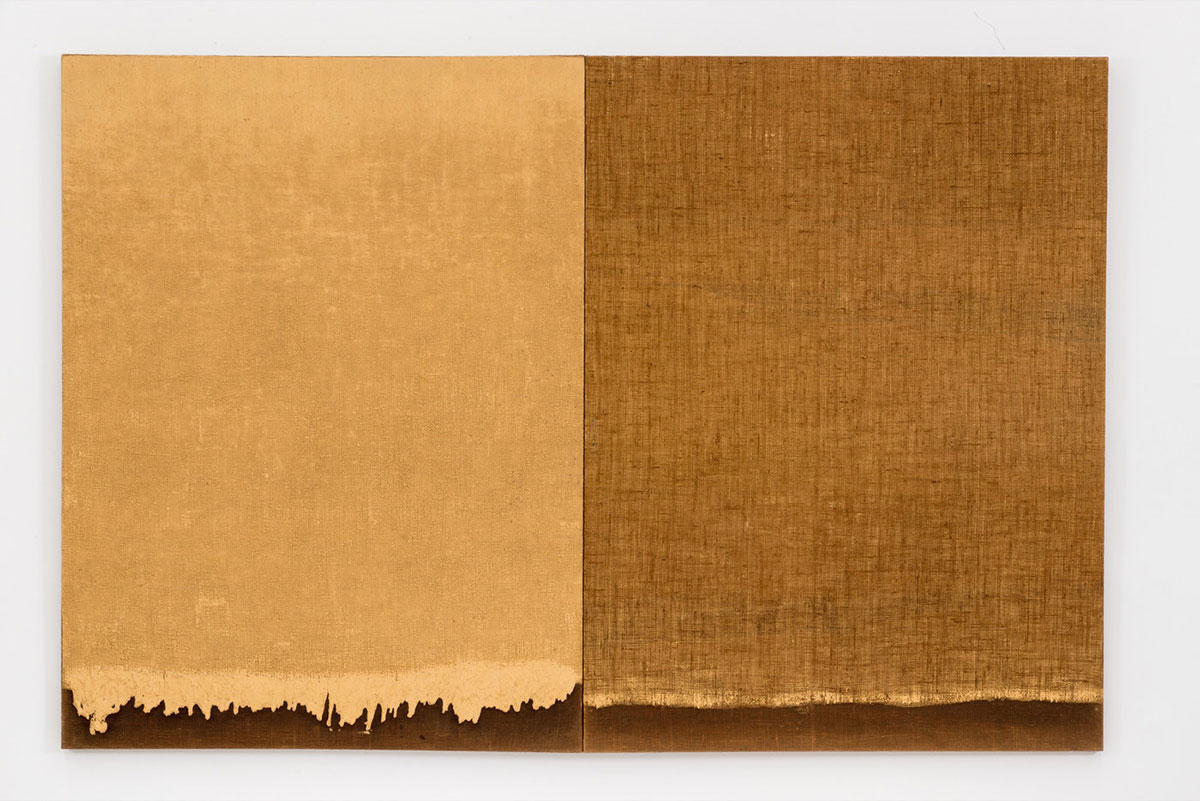

Ha Chong-hyun’s solo exhibition in Los Angeles takes a retrospective look at his pioneering practice and is the first to present “Conjunction 20-200” (2020), a monumental installation of eight towering canvases, each of which Ha painted with one of the signature techniques that he developed during the past five decades. The compositions in this massive polyptych are placed in dialogue with thirteen paintings dating from 1972 to 2021. “Conjunction 20-200” stands atop rolls of raw hemp that unfurl onto the floor, interwoven with barbed wire. For Ha, this arrangement evokes the earth and refers to his earliest series of multimedia works, made between 1969 and 1973 when he was a member of the artist collective AG (Avant-Garde Association). During this period, he created site-specific installations out of atypical materials—including plaster, timber, newspaper, and, most notably, a series of burlap supports embedded with barbed wire. Both materials were at once mundane yet politically charged features of the urban landscape in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950–53): burlap sacks were used to transport food aid from the United States, while barbed wire fences ring the country’s military bases and divide the Korean peninsula to this day. Ha’s appropriation of these materials broke with the two-dimensional conventions of painting while evoking the authoritarian atmosphere of the postwar era. Ha’s investigations in the early 1970s yielded surfaces juxtaposed with materials that had radically different physical properties. He often used rough hemp canvases, painted them all white or all black, shaped them as a perfect square or long rectangle, and lined them with gridlike formations of barbed wire, metal springs, nails, and other common industrial materials. Ha created “Work 73-13” (1973) during the military dictatorship of Park Chung Hee, who had tightened his grip on all aspects of life in South Korea. The way in which the cagelike barbed wire entraps the hemp and physically presses into the fleshlike surface provokes a visceral reaction and alludes to the onset of Park’s reign of terror during which Park declared martial law and installed a repressive authoritarian regime. With the Korean War and the division of the peninsula, South Korea functioned as a military station for the United States throughout the Cold War, while the North was sanctioned by the Soviet Union. The barbed-wire fence that protected the U.S. Army bases was a familiar sight for many living in Seoul, as were American soldiers. In this sense “Work 73-13” is a powerful reminder and embodiment of the Korean War and its long, conflicted aftermath. In 1974, Ha began his ongoing “Conjunction” series, which explores the material fusion of paint and canvas through his original bae-ap-bub (back-pressure) method, in which he presses viscous oil paint through the reverse of the coarsely woven cloth so it permeates the fabric and protrudes through the surface. Thereafter he variously brushes, smears, scrapes, and even scorches the paint in pursuit of an abstract composition that exposes the essence of its component materials. This experimental approach to painting as method rather than representation situated Ha as part of a movement that later came to be known as Dansaekhwa, which included peers such as Chung Sang-hwa, Kwon Young-woo, Lee Ufan, Park Seobo, and Yun Hyong-keun. Working in a reductionist aesthetic, these artists variously pushed paint, soaked canvas, dragged pencils, ripped paper, and otherwise manipulated materials in ways that transgressed the distinctions separating ink painting from oil, painting from sculpture, and object from viewer. Six decades on, Ha continues to find new ways to expand the vernacular of his “Conjunction” paintings.

Photo: Ha Chong-hyun, Conjunction 20-200, 2020, © Ha Chong-hyun, Photo: Josh Schaedel, Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe Gallery

Info: Blum & Poe Gallery, 2727 South La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 10/9-22/12/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.blumandpoe.com/

Right: Ha Chong-hyun, Conjunction 17-31, 2017, Oil on hemp, 46 1/8 x 35 7/8 inches, © Ha Chong-hyun, Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe Gallery