PREVIEW: Thornton Dial-I, Too, Am Alabama

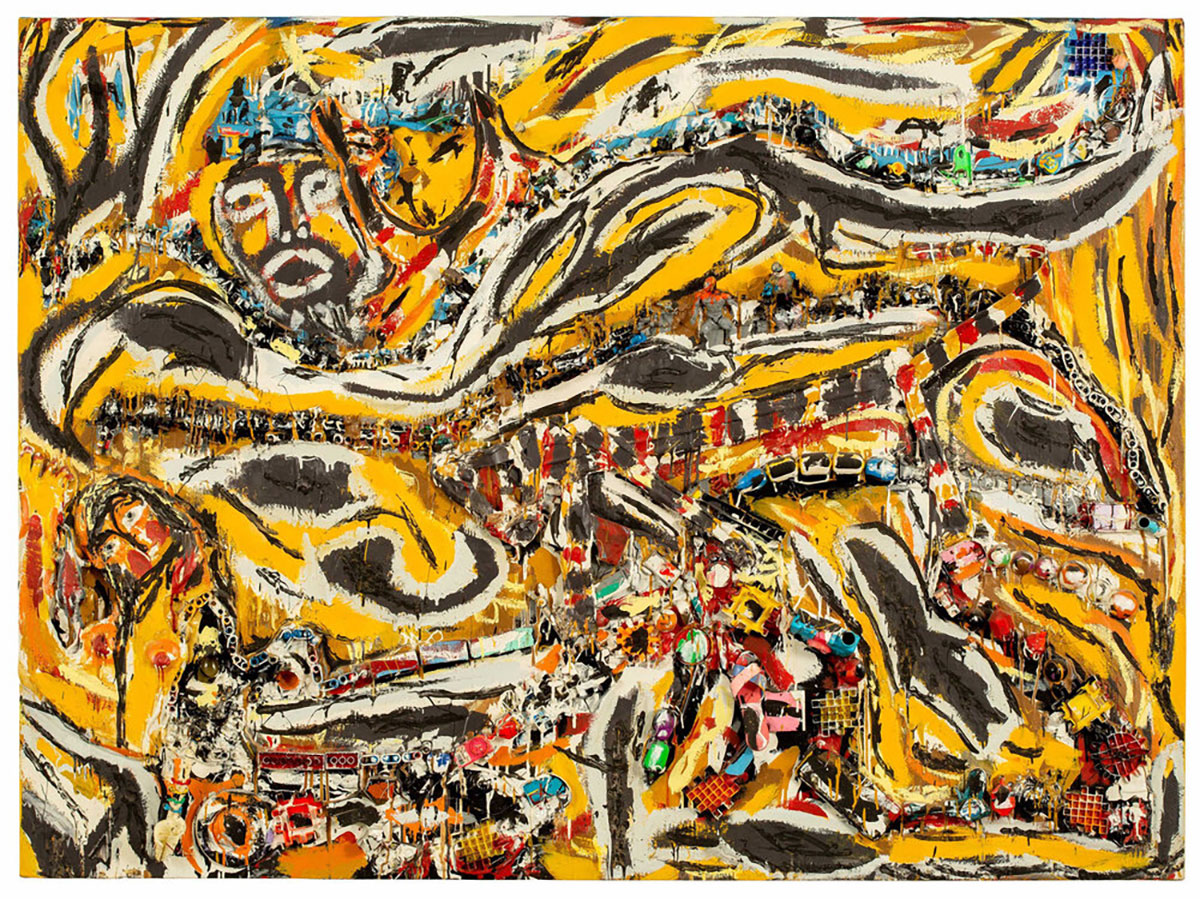

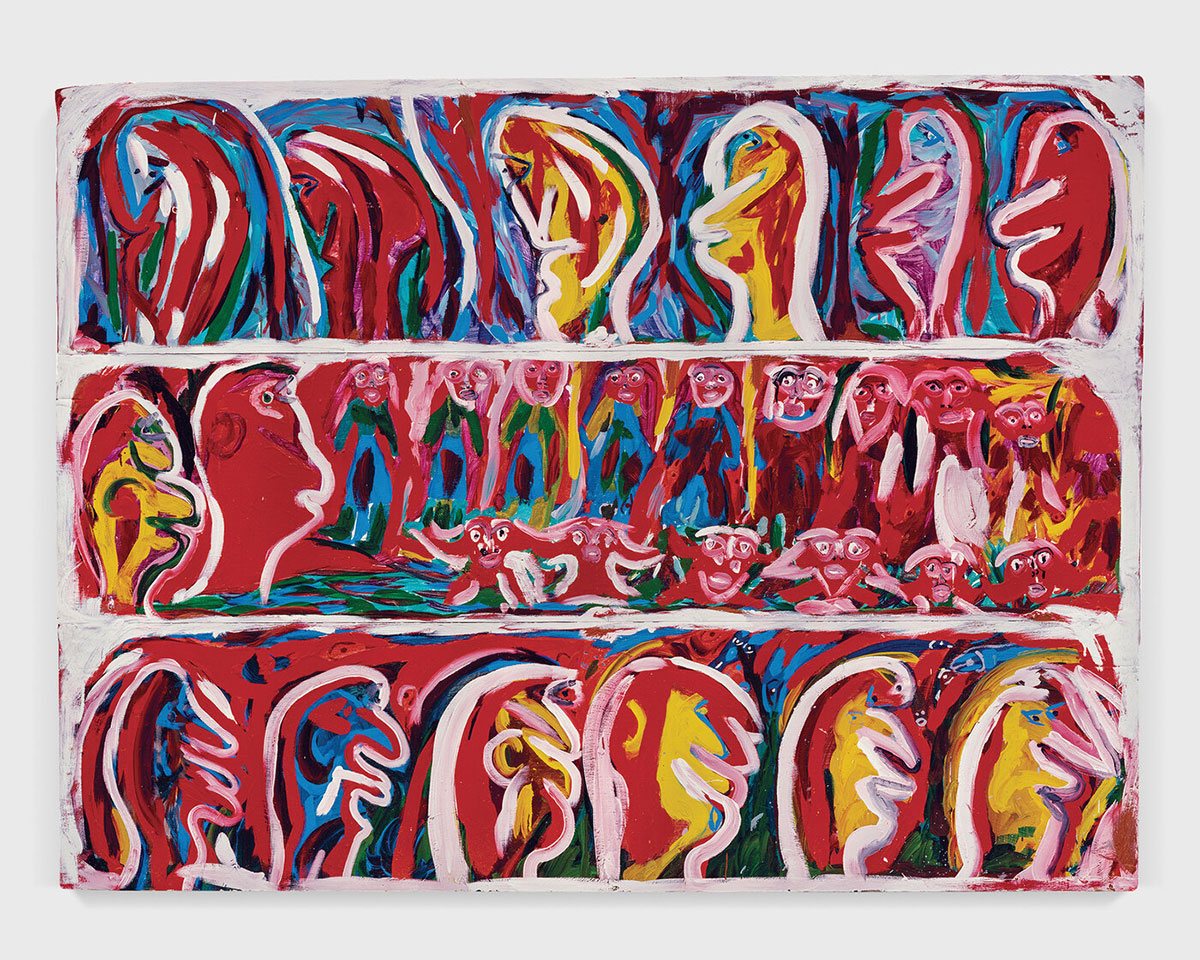

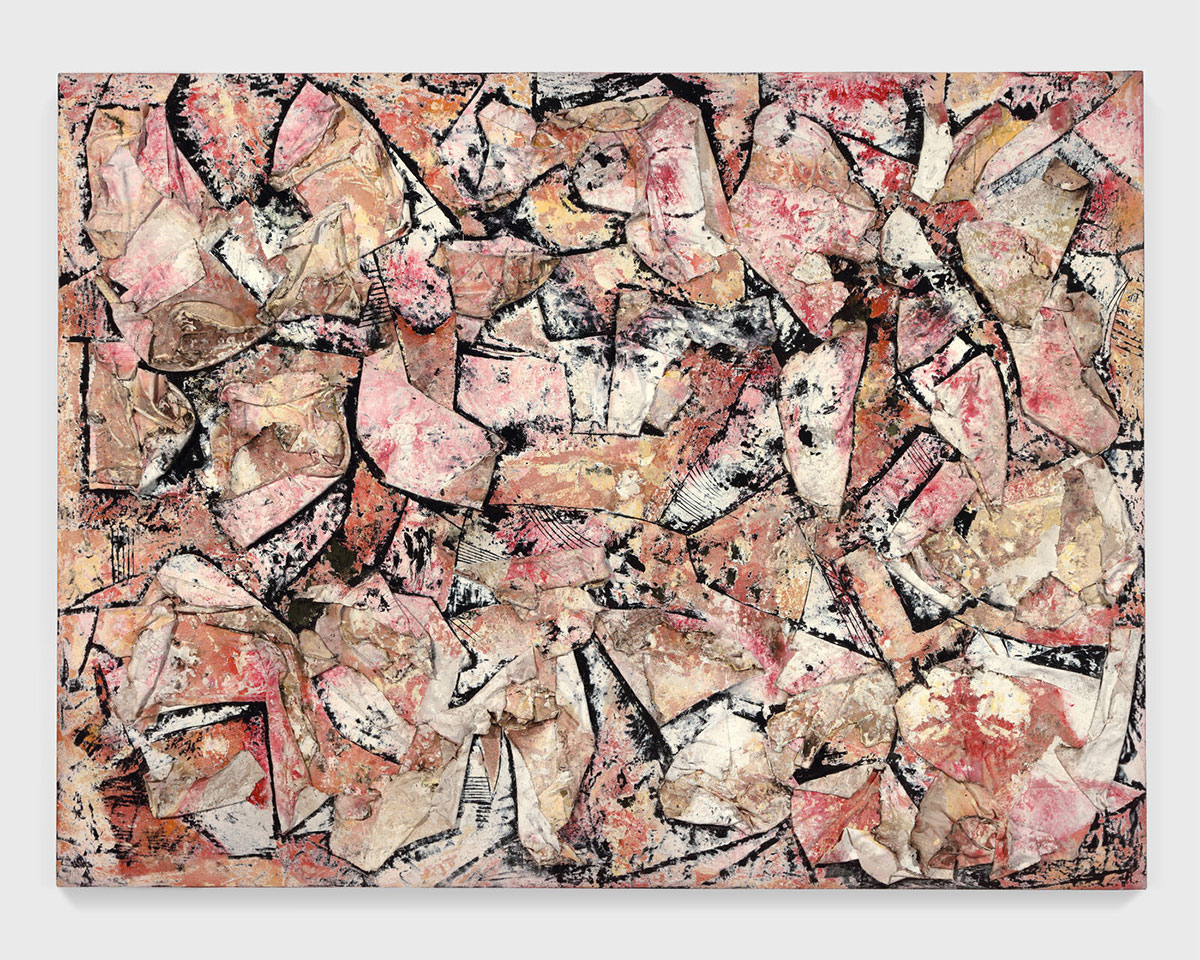

One of the most revered contemporary self-taught artists, Thornton Dial was famous for yard show-influenced, mixed media pieces that used discarded everyday objects to symbolize the history and experience of African Americans in the South. While he did not belong to any formal school of art, Dial is widely considered to be one of the most important voices in the outsider art movement.

One of the most revered contemporary self-taught artists, Thornton Dial was famous for yard show-influenced, mixed media pieces that used discarded everyday objects to symbolize the history and experience of African Americans in the South. While he did not belong to any formal school of art, Dial is widely considered to be one of the most important voices in the outsider art movement.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts Archive

“I, Too, Am Alabama” is the first retrospective covering Thornton Dial’s entire career. This is also the first large-scale exhibition of his work in his home state of Alabama. The exhibition features masterworks spanning Dial’s entire career including sculpture, works on paper, and assemblages, with many works that have never been previously exhibited or published. The exhibition features significant loans from the Dial family, Alabama institutions, and private collections across the United States. Thornton Dial was born on September 10, 1928 on a cotton plantation near Emelle, Alabama. His mother, Mattie Bell, was an unwed teenager at the time and asked her grandmother to raise her child. Dial lived with his great-grandmother on the sharecropper farm* of his cousin, Buddy Jake Dial, and took his last name. Dial recalls that he spent more time working on the farm than attending school: “They told me, ‘earn to figure out your money and write your name. That’s as far as a Negro can go”. At age 12, Thornton Dial dropped out of school. Even though he had made it through third grade, he could not read or write. Soon after, Dial moved to live with family in Bessemer, Alabama and after working a series of odd-jobs, found steady employment as a metalworker at the Pullman Standard Plant. While Dial never received any formal training in art or sculpture, the skills he learned as a metalworker and handyman served as a foundation for his artistic techniques. As a hobby and side job, Dial picked up cast-off objects and used them as materials to make what he just called “things” practical and decorative items to sell around the neighborhood. When the Pullman Standard Plant closed in 1981, Dial devoted his time to creating more and more sophisticated “things” producing them and, in his own words, “putting them out there for someone to like”. Dial’s art caught the attention of Lonnie Holley, a black folk-artist who, like Dial, mostly made art and sculptures from found objects. In 1987, Holley introduced Dial’s work to William Arnett, an Atlanta, Georgia-based art collector with a special interest in the self-taught black artists of the South. For the first time in his life, 59-year-old Dial and his work became a centerpiece of Arnett’s Souls Grown Deep Foundation. From there Dial’s artwork made its way first into local museum and gallery exhibits and then into renowned museums across the United States. Only at that point did Dial consider his “things” to be works of art. Thornton Dial’s work addresses American sociopolitical exigencies such as war, racism, bigotry and homelessness. He draws attention to these themes using the overlooked and under-considered material artifacts of everyday American life. Combining paint and found materials, Dial constructs large-scale assemblages with cast-away objects ranging from rope to bones to buckets. Works such as “Black Walk” and “The Blood of Hard Times” for example, use corrugated tin and other dilapidated pieces of metal to refer to the destitute bodies and vernacular architecture of the rural South. The symbol of the tiger is also a primary visual trope in Thornton Dial’s oeuvre. Artist and African-American art historian David C. Driskell explained Dial’s use of the tiger as an allegory for survival and an implicit reference to the struggle for civil rights in the United States. Many of Dial’s most famous works make use of both the origin and positioning of found objects to provide commentary on black life in the South, history, society, or current events. His “Last Day of Martin Luther King” (1993) depicts King as a tiger (Dial’s symbol for the strength of black people) made of mop strings. His sculpture “Lost Cows” (2001) was made from the bones of cattle Dial himself owned. His impressive “History Refused to Die” incorporates torn and stained clothing, wire, and other common materials as well as okra stalks and roots. The plant serves as a metaphor for the shared history—the “roots”—of people whose personal genealogies tie back to Africa. Widely associated with Southern cuisine, okra is indigenous to Africa and, like many other foodstuffs, came to the Americas via the international slave trade. Its presence in Dial’s sculpture evokes the ecological transplantation that paralleled the forced displacement and enslavement of millions of Africans throughout the New World. Dial continued to make art until his death on January 25, 2016. For Dial, art was tangible evidence of his freedom—something he did not take for granted—and a path to a brighter collective future for us all. He often examined events of the past but looked optimistically, if carefully, towards the future. In his own words, “I respect the past of life, but I don’t worry too much about it because it’s done passed. The struggles that we all have did, those struggles can teach us how to make improvement for the future. Art is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world. It can lead peoples through the darkness and help them from being afraid of the darkness. Art is a guide for every person who is looking for something. That’s how I can describe myself: Mr. Dial is a man looking for something.”

* Sharecropping is a system where the landlord/planter allows a tenant to use the land in exchange for a share of the crop. This encouraged tenants to work to produce the biggest harvest that they could, and ensured they would remain tied to the land and unlikely to leave for other opportunities.

Photo: Thornton Dial, Lost Cows, 2000-2001, Cow skeletons, steel, golf bag, golf ball, mirrors, Splash Zone, and enamel, 76 1/2 x 91 x 52 inches, © Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Collection of de Young Museum, San Francisco

Info: Curator: Paul Barrett, Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts (University of Alabama), 1221 10th Avenue South, Birmingham, AL, USA, Duration: 9/9-10/12/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 12:00-17:00, www.uab.edu/home/

Right: Thornton Dial, Payday to Payday: Stores on Every Corner, 1993, Cloth, metal, wood, tire tread, Splash Zone, oil, enamel, and spray paint on canvas over wood, 110 x 80 x 4 inches, © Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York