PRESENTATION: Future Bodies from a Recent Past

The exhibition “Future Bodies from a Recent Past—Sculpture, Technology, and the Body since the 1950s” brings to life a hitherto little-noticed phenomenon in art, and more particularly in sculpture: the reciprocal interpenetration of body and technology. With more than 100 works and several large-scale installations by around 60 artists—primarily from Europe, the United States, and Japan—the exhibition focuses on the major technological changes since World War II and their influence on our ideas of the body.

The exhibition “Future Bodies from a Recent Past—Sculpture, Technology, and the Body since the 1950s” brings to life a hitherto little-noticed phenomenon in art, and more particularly in sculpture: the reciprocal interpenetration of body and technology. With more than 100 works and several large-scale installations by around 60 artists—primarily from Europe, the United States, and Japan—the exhibition focuses on the major technological changes since World War II and their influence on our ideas of the body.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Museum Brandhorst Archive

Contemporary art is characterized by an examination of the relationship between the body and technology. Many artworks from recent years reflect how we experience ourselves and our environments in the highly technological and networked present. Yet this relationship can be traced far back into the 20th century. The post-war period was marked by rapid technological change, which has become the pinnacle of ideological instrumentalization. It satisfied the need for novelty as much as the need to overcome the traumas of war. At the same time, technology became a crystallization point for global threats and fears of change, or even loss of control. Within this broad spectrum, ranging from euphoria about the future to critical distancing, sculpture also engaged with new technologies. These served equally as means of emancipation as surveillance and (external) control, and profoundly influenced our understanding of bodies. Across two floors of the museum, “Future Bodies from a Recent Past” presents for the first time a structured frame of reference for this narrative, ranging from the post-war period to the present. Throughout, it becomes clear that sculpture is particularly well suited to picking up and reflecting on these changes—not only because sculptures are physical objects in space and therefore provide a possibility for projecting our own corporeality, but also because they share their materials and production methods with the world that surrounds us. This permeability to outside influences is also evident in the works included here. The exhibition charts a journey through forms and modes of expression in sculpture, which have changed more in the last 70 years than probably ever before in its long history. How has the relationship between humans and technology shifted since the 1950s? Can the boundaries still be clearly drawn? Where do our digital extensions, such as computers or cell phones, begin and end? What does this mean for our ideas of corporeality and materiality? And what are the social implications of these developments for our (collective) self-understanding? The exhibition explores these core questions.

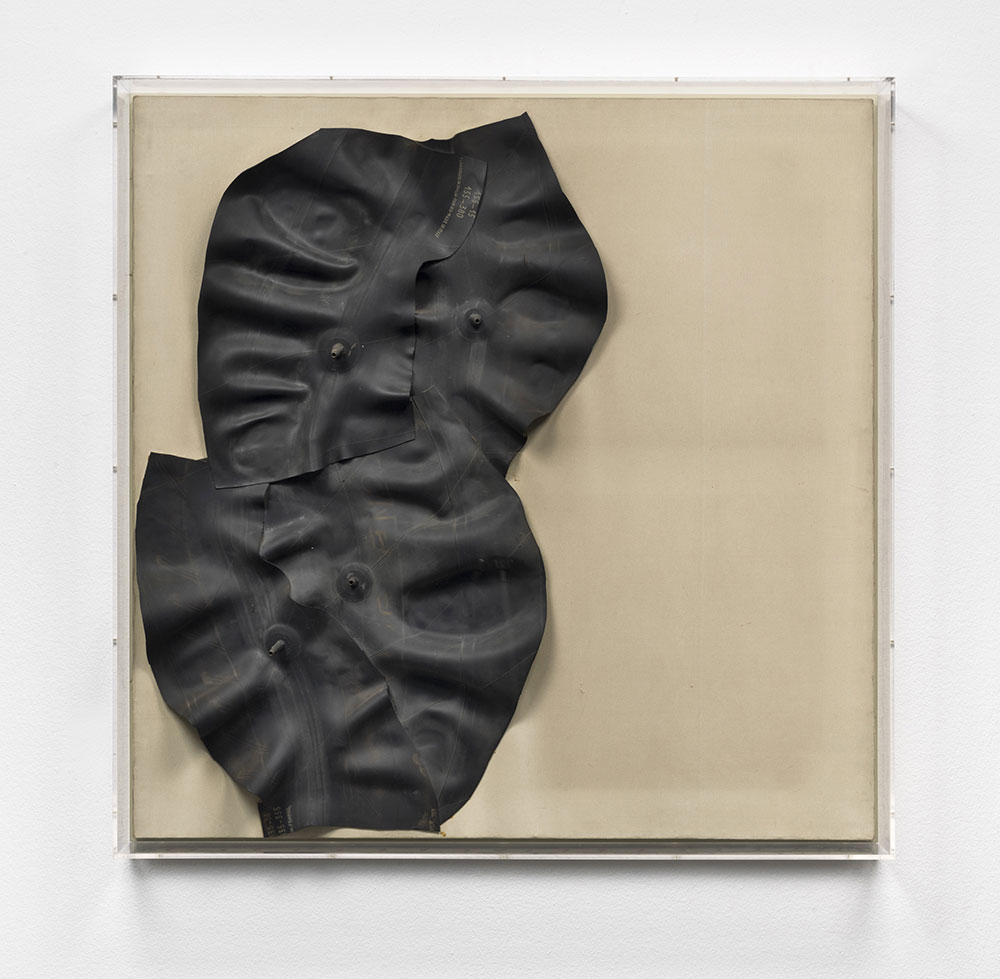

“Sheets of Vagina Second Present” by the Japanese artist Genpei Akasegawa is equally impressive for both its size and itsmateriality. He created an object of almost overwhelming physicality using blood-red inner tubes fromthe tyres of a truck that were cut open and sewn back together, and to which a hubcap and vacuumtubes were applied. The title “Sheets of Vagina (Second Present)” refers explicitly to the female sexualorgan. Originally, hydrochloric acid dripped from a long pipette, integrated into the work, onto an object below. The female sexual organ—the point of contact between inside and outside—had beenreplaced by leaking machine parts. “Sheets of Vagina” consists of waste products, suggesting thesurplus of Japan’s economic expansion during the 1950s and 1960s. Yet for all the changes in Japanese society, freedoms relating to sexuality and procreation continued to be suppressed. Abstractenough not to invite censorship, the fleshy materials and forms in Akasegawa’s work are all the morecharged, testifying to an alien, machinic productivity. Paweł Althamer often includes people from his own immediate environment in his artworks. The life-size group of figures, “Bródno People” is based on Auguste Rodin’s “Les Bourgeois de Calais” (The Burghers of Calais, 1889) and its depiction of the joint sacrifice of six citizens in 1347 to save their town. Here, Althamer creates a contemporary interpretation, together with people from the prefabricated housing estate in the Bródno district of Warsaw, where he himself grew up. Each figure represents a self-portrait of one of the neighbors and of Althamer himself. Reminiscent of science fiction films, the figures, like cosmonauts, land in the museum space on their wheeled undercarriage. Through the use of found materials, such as stuffed and silver-sprayed clothing, pieces of scrap metal, and plastic wrap, they take on their own futuristic character while emphasizing the social and political circumstances of the work. With its origins in collective practice, “Bródno People” tells both of a past and a present in post-communist Poland, and of a possible shared future.

Mark Leckey’s large-scale installation “UniAddDumThs (ANIMAL)” offers an unusual perspective on the history of technology. In 2013, the British artist was invited to curate an exhibition. Along the lines of the terms “man,” “machine,” and “animal,” Leckey selected artworks and objects with references to technology, popular culture, and human history. He presented them side by side in large displays. Thus, objects (including the technological imaginary) from different eras and contexts intersected. At the end of the exhibition, Leckey decided to preserve the objects for himself by creating (authorized) copies and reproductions with the help of analog and digital means such as 3D prints, photographs, and even cardboard standees. This is how “UniAddDumThs” came into being. The starting point for Leckey’s selection was the observation that technology has changed our relationship to things. After all, our highly digitalized environment is increasingly populated by “animated” and “networked” objects: computers talk to us, our refrigerator knows what we like to eat. The belief in the inherent life of supposedly “dumb things” is becoming ever more normal. This links our technologized world with the animistic thinking of premodern times when objects were perceived as alive or even possessing a soul.The group of sculptures, by Aleksandra Domanović revolves around the Belgrade Hand, the world’s first bionic handprosthesis equipped with five fingers and a sense of touch. Yugoslav engineer Rajko Tomović invented it in 1963 for soldiers who had lost their hands in World War II, and it was soon seen as an important landmark in the development of robotics. For her sculptures, Domanović recreated the shape of the Belgrade Hand using software, had it 3-D printed in polyamide and polyurethane plastic, and coatedwith brass, aluminum, and a soft-touch surface. The finger positions of “Fatima”, “Mayura Mudra” and “Little Sister” reference symbolic gestures from different cultural traditions and times. Similarly,the works are ciphers for Domanović’s exploration of the significant but mostly overlooked role women have played in technological developments. The timeline accompanying the sculpturesreflects this history of technology and its gender-specific disparities.

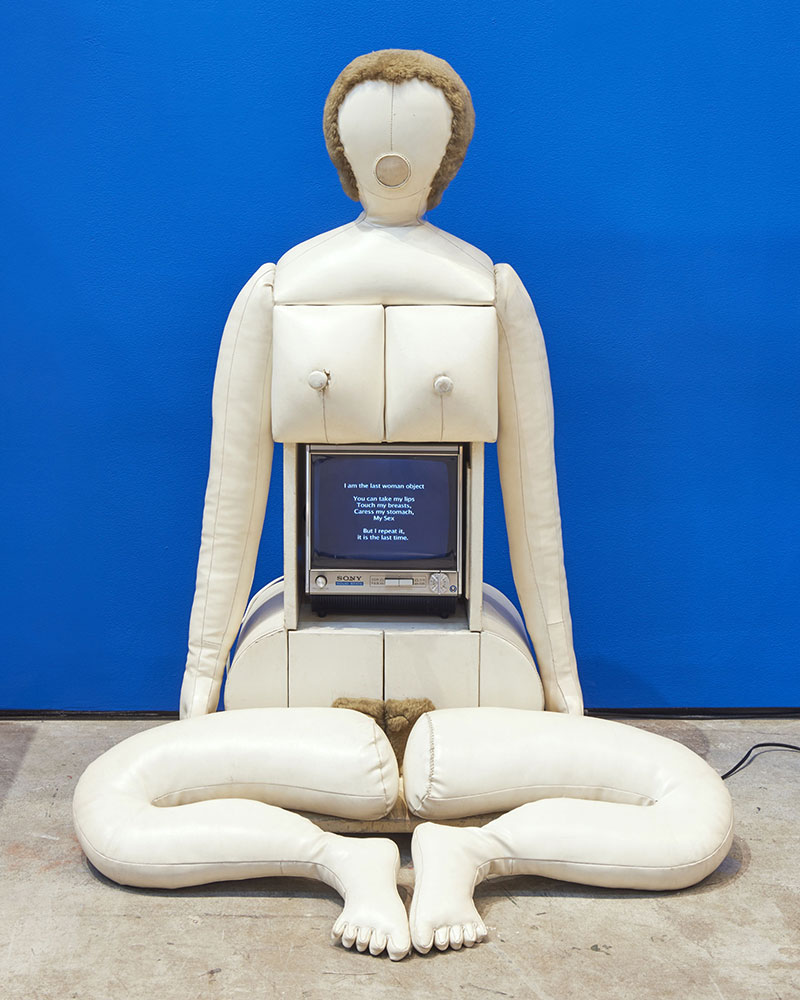

Nicola L.’s “Little TV Woman: ‘I Am the Last Woman Object’”, a figure sitting on the floor, equipped with drawers instead of breasts and a television instead of a belly—was first displayed in the window of a Paris jewelry boutique in 1969. A sculptural piece of furniture, it is one of a series of works that the artist described as “functional objects” intended for everyday use. They bear witness to the blending of art and commodity culture that characterized Pop Art at the time. But Nicola L. also tackled stereotypical notions of women in the domestic environment and in the media. “I am the last woman object. You can take my lips, touch my breasts, caress my stomach, my sex. But I repeat it, it is the last time,” reads the text on the monitor. “Little TV Woman” invites interaction, while at the same time questioning it. In keeping with the feminist movements of the 1960s, Nicola L. criticized how female bodies are turned into objects or commodities. In her works artist Nairy Baghramian, who was born in Isfahan, Iran and lives in Berlin, addresses thecomplex relationship between architecture, object, and the human body, exploring the political potential that can lie in sculptural forms. In her sculpture “Scruff of the Neck” bulbous tooth-like forms made of white plaster, partially covered with beeswax, are attached to unevenly shaped sheets and rods of aluminum. In its form and materiality, the abstract sculpture is reminiscent of oversized dentures. Yet with its bridges, braces, and retainers, “Scruff of the Neck” marks not so much the human oral cavity as the museum itself as unstable and in need of correction: the sculpture docksonto the walls of the exhibition space and alludes to the institutional and architectural conditions under which (sculptural) bodies are housed, presented, and choreographed.

Works by: Genpei Akasegawa, Paweł Althamer, Nairy Baghramian, Joachim Bandau, Matthew Barney, Alexandra Bircken, Louise Bourgeois, Robert Breer, John Chamberlain, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Shu Lea Cheang, Jesse Darling, Stephanie Dinkins, Aleksandra Domanović, Melvin Edwards, Bruno Gironcoli, Robert Gober, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Nancy Grossman, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Eva Hesse, Judith Hopf, Rebecca Horn, Tishan Hsu, Edward Ihnatowicz, Arthur Jafa, Motoharu Jōnouchi, KAYA, Kiki Kogelnik, Shigeko Kubota, Tetsumi Kudo, Yayoi Kusama, Nicola L., Mark Leckey, Sarah Lucas, Bruce Nauman, Senga Nengudi, Kiyoji Ōtsuji, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Eduardo Paolozzi, Friederike Pezold, Julia Phillips, Walter Pichler, Seth Price, Carol Rama, Germaine Richier, Niki de Saint Phalle, Hans Salentin, Ashley Hans Scheirl, David Smith, Alina Szapocznikow, Takis, Atsuko Tanaka, Paul Thek, Jean Tinguely, Hannsjörg Voth, Franz West

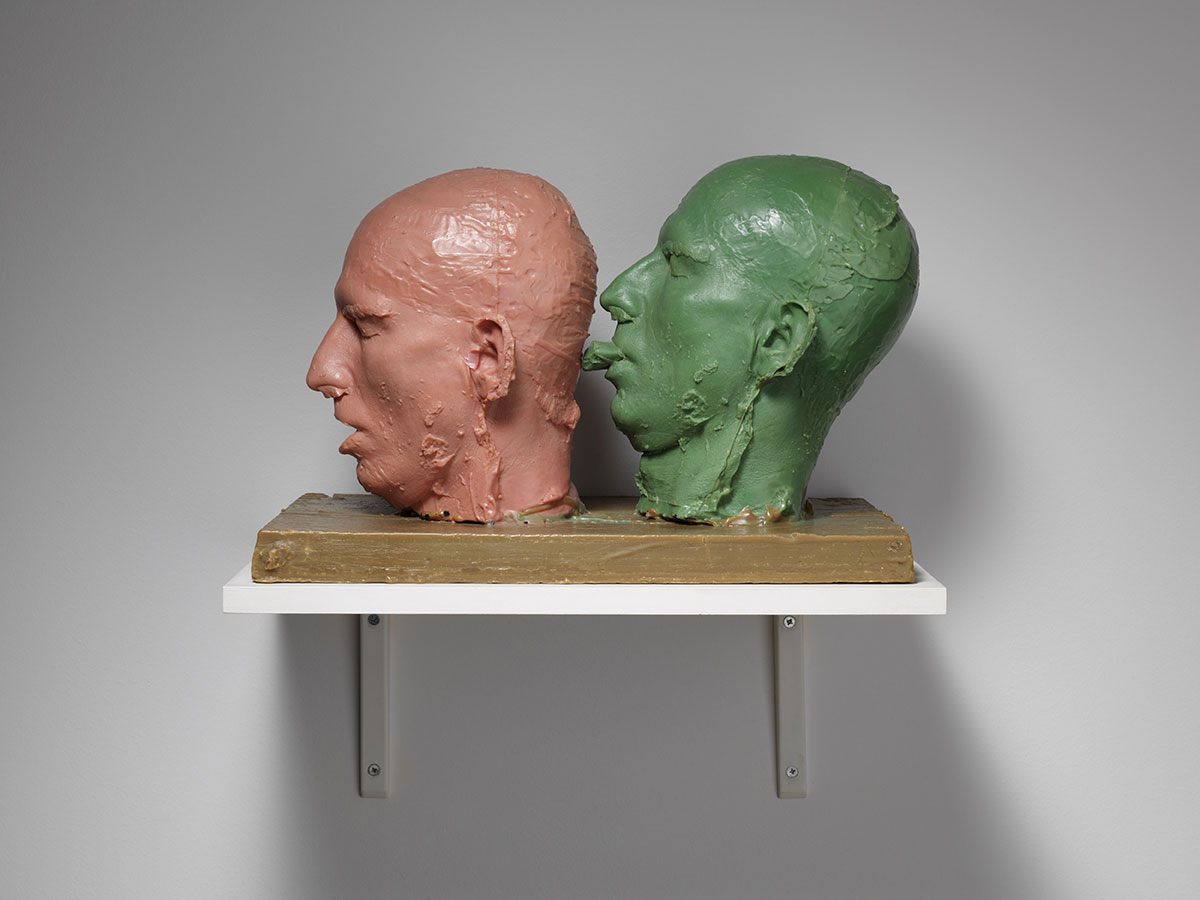

Photo: Bruce Nauman , 2 Heads on Base #1, 1989 , Wax , 31 x 47 x 29 cm, Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 Photo: Haydar Koyupinar, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Info: Curators: Patrizia Dander and Franziska Linhardt, Museum Brandhorst, Theresienstraße 35a, Munich, Germany, Duration: 2/6/2022-15/1/2023, Days & Hours; Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu 10:00-20:00, www.museum-brandhorst.de/

Center: Aleksandra Domanović Mayura Mudra, 2013, Laser sintered PA plastic, polyurethane, Soft-Touch and brass finish, UV print on acrylic glass, 157 × 30 × 30 cm, Private collection, © Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles Photo: Gunter Lepkowski

Right: Aleksandra Domanović, Fatima, 2013, Laser sintered PA plastic, polyurethane, Soft-Touch and brass finish, UV print on acrylic glass, 157 × 30 × 30 cm, Geddert Hronjec Collection, © Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles Photo: Gunter Lepkowski

Right: Joachim Bandau Transplantationsobjekt VI (Kölner Spritze), 1968, Mannequin segments, fiberglass-reinforced polyester, PVC tubes, mixed media, lacquer, C-hose coupling, PVC hose, 190 x 93 x 33 cm, Private Collection, Riehen, Schweiz, © Joachim Bandau. Photo: Elisabeth Greil, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Museum Brandhorst, Munich

Right: Nancy Grossman Potawatami, 1967, Leather, rubber, and metal assemblage on plywood, 60.3 × 96.5 × 29.8 cm, © Nancy Grossman. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY

Right: Joachim Bandau, Großes Silbernes Monstrum (Version 2), 1971 / 1974 / 2016, Mannequin segments, fiberglass-reinforced polyester, mixed media, lacquer, aluminum, C-hose couplings, with or withouth Vacuflex hose, casters, 236 x 77 x 100 cm, © Joachim Bandau