ART CITIES: Zurich-Erna Rosenstein

Erna Rosenstein’s six-decade career was fueled by the formation of prewar artistic, intellectual and political affiliations, and is expressed in a constant oscillation between autobiographical figuration and biomorphic abstraction. While Rosenstein produced artworks in the prewar period, nothing survived the war; instead, she filtered the memories of her early life through fantastical stories and enchanting visual landscapes.

Erna Rosenstein’s six-decade career was fueled by the formation of prewar artistic, intellectual and political affiliations, and is expressed in a constant oscillation between autobiographical figuration and biomorphic abstraction. While Rosenstein produced artworks in the prewar period, nothing survived the war; instead, she filtered the memories of her early life through fantastical stories and enchanting visual landscapes.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Hauser & Wirth Gallery Archive

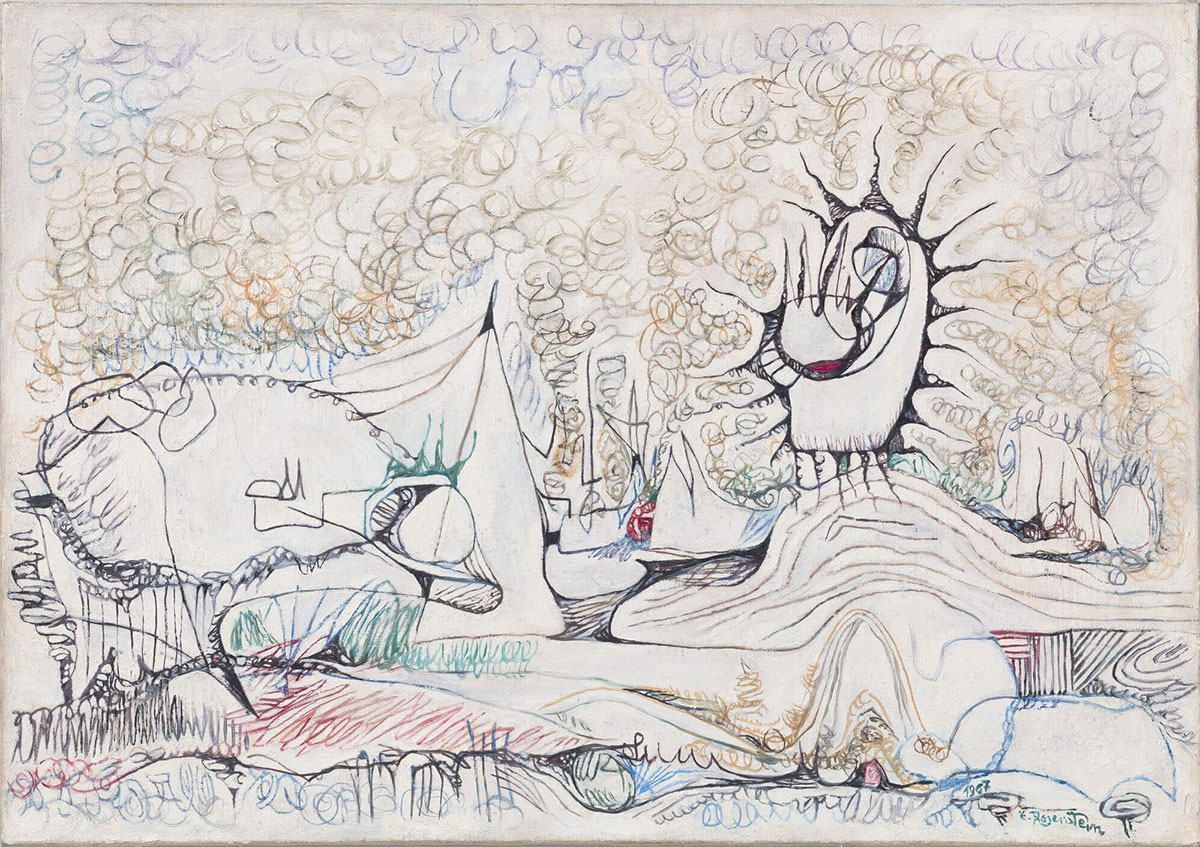

Grappling with themes of memory, trauma, longing and loss, Erna Rosenstein used paint, ink and found materials to suggest a world tinged with allegory, enchantment and fairytale. The exhibition “Erna Rosenstein” brings together fifty works, including works from the Estate of Erna Rosenstein, that are exhibited publicly for the first time since the artist’s death in 2004. Abstract paintings dating from the early 1950s to the end of the 1970s showcase the intense focus of those two decades of her practice and reflect the political and personal turmoil of those years. “Poświata (Afterglow)” (1968) depicts a babbling brook running down from the valleys and rolling hills of a pastel landscape rendered in billowing pinks and citron greens, while “Kwiaty piekła (Hell Flowers)” (1968) is saturated with bodily reds in which biological forms vibrate, conjuring the sensations of nerves or internal organs. This work is particularly charged with personal meaning: it was made in 1968, a turbulent year for Polish Jews who had survived the Holocaust as many were forced to emigrate from Poland by the Communist government in an antisemitic purge. Rosenstein opted to stay in Poland, a painful scenario reflected in the sometimes-violent imagery that surfaced in her work of this period. These works are exemplary of the artist’s abstract practice in which biomorphic shapes undulate and pulse on the surface of the canvas. The forms often evoke bodily sensations of inner landscapes that belong to the mystical realm of the psyche. Often discussed in regard to their alchemical qualities, Rosenstein’s abstract landscapes are rooted in the unconscious mind and arouse otherworldly and cosmological allusions. Also on display are Rosenstein’s deeply autobiographical paintings, shifting to the figurative side of the artist’s practice. Her parents’ murder during the Holocaust is a subject she returns to repeatedly in multiple drawings and paintings across the decades. She does not attempt to directly depict their brutal murder in realistic terms, instead transforming this primal scene into disconcerting, often magically tinted dreamscapes. Such a painting is “Osobna pora (Separate Season)” (1971), depicting her mother Anna’s head floating in an abstract landscape. The apparition of Anna’s head recurs six times in this scene, yet her smiling face seems to both defy death and time as she exists suspended in the artist’s memory. The traumatic loss of her parents is also the subject of “Bardzo Dawne (From Long Ago)” (undated). This physically small yet monumentally important painting not only depicts the traumatic murder of Rosenstein’s parents, but it also suggests the fairy tale as the central form and conceptual core of her entire practice. This shift towards a more figurative style is shown in a selection of expressive drawings that span from the early 1970s to the 1990s. On view are a group of eight works on paper in their original authorial framing suspended from the ceiling, depicting dream-like imagery that has become a hallmark of her oeuvre. The exhibition also presents a selection of untitled assemblage sculptures made by the artist during the early 1980s, a period of martial law in Poland when scarcity prevailed. These works – among them a waste basket, a cigarette pack with eyes and an old purse with teeth – transform the most humdrum bric-a-brac into the substance of art and oscillate between the figural and the abstract. They reflect the childlike and whimsical aspects of Rosenstein’s sublimating practice and echo the artist’s early Surrealist lexicon of expression. Rosenstein also applied her drawing practice to found objects, as seen in ‘Untitled’ (1973). Comprised of a coffee table from Rosenstein’s studio, ‘Untitled’ offers an insight into her dedicated practice which often led to the blurring of boundaries between life and art in her work. Rosenstein’s “Szafa (Cabinet)” (ca. 1960 – 2004), an everyday cabinet, functioned as a piece of furniture in the artist’s home studio, housing her writings, sketchbooks and correspondence. A ‘cabinet of curiosities’ of sorts, it operated dually as a repository for her creative impulses: Rosenstein adorned the cabinet’s doors with personal references and trinkets, collecting collaged found objects, postcards, photographs and reproductions of Flemish paintings. Rosenstein’s writings coexisted alongside her visual artistic practice from as early as the 1940s when she began to publish children’s tales in Polish magazines. After the birth of her son in 1950, she commenced writing fairytales that, like her paintings, drew their narratives from the tension between magical realism and a bleak, pragmatic reality replete with loneliness and misfortune. Often, her writings become allegories of her own Polish Jewish experience with antisemitism.

Photo: Erna Rosenstein, Kwiaty piekła (Hell Flowers), 1968, Oil on canvas, 49 x 69.8 x 2 cm / 19 1/4 x 27 1/2 x 3/4 in, © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Info: Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Limmatstrasse 270, Zürich, Switzerland, Duration: 2/9-19/11/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri 11:00-18:00, Sat 11:00-17:00, www.hauserwirth.com/

Right: Erna Rosenstein, Untitled, 1984, Molded plastic, paint, wire, 26.7 x 19.1 x 5.1 cm / 10 1/2 x 7 1/2 x 2 in, © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Right: Erna Rosenstein, Untitled, 1984, Molded plastic, paint, wire, 26.7 x 19.1 x 5.1 cm / 10 1/2 x 7 1/2 x 2 in, © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Right: Erna Rosenstein, Łzy (Tears), 1993, Oil and glass on canvas, 71.6 x 51.5 x 2.9 cm / 28 1/4 x 20 1/4 x 1 1/8 in, © The Estate of Erna Rosenstein / Adam Sandauer, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Gallery