ART CITIES: Venice-Human Brains, Part II

Fondazione Prada’s initiative dedicated to neuroscience, “Human Brains,” surveys different fields: from neurobiology to philosophy, from psychology to neurochemistry, from linguistics to artificial intelligence. Through a convergence of diverse scientific approaches, the human brain is examined in the plural to underline its intrinsic complexity and the irreducible singularity of each individual (Part II).

Fondazione Prada’s initiative dedicated to neuroscience, “Human Brains,” surveys different fields: from neurobiology to philosophy, from psychology to neurochemistry, from linguistics to artificial intelligence. Through a convergence of diverse scientific approaches, the human brain is examined in the plural to underline its intrinsic complexity and the irreducible singularity of each individual (Part II).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fondazione Prada Archive

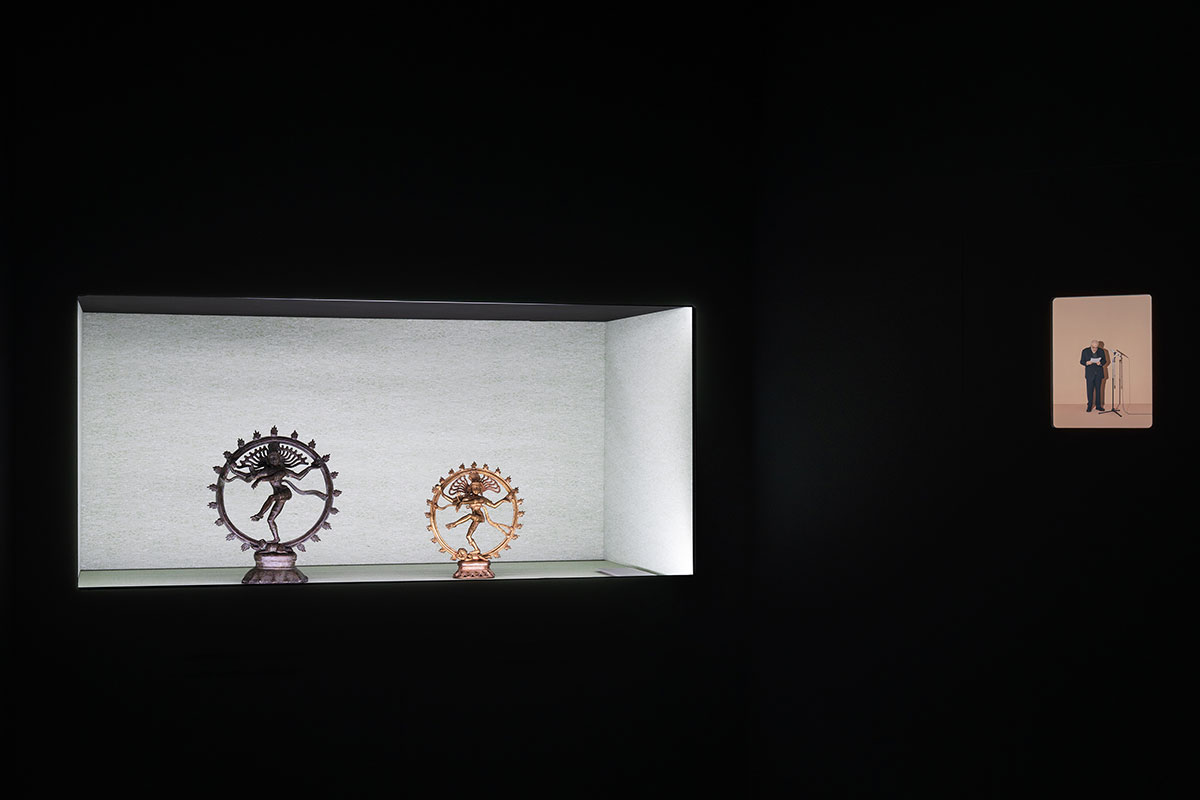

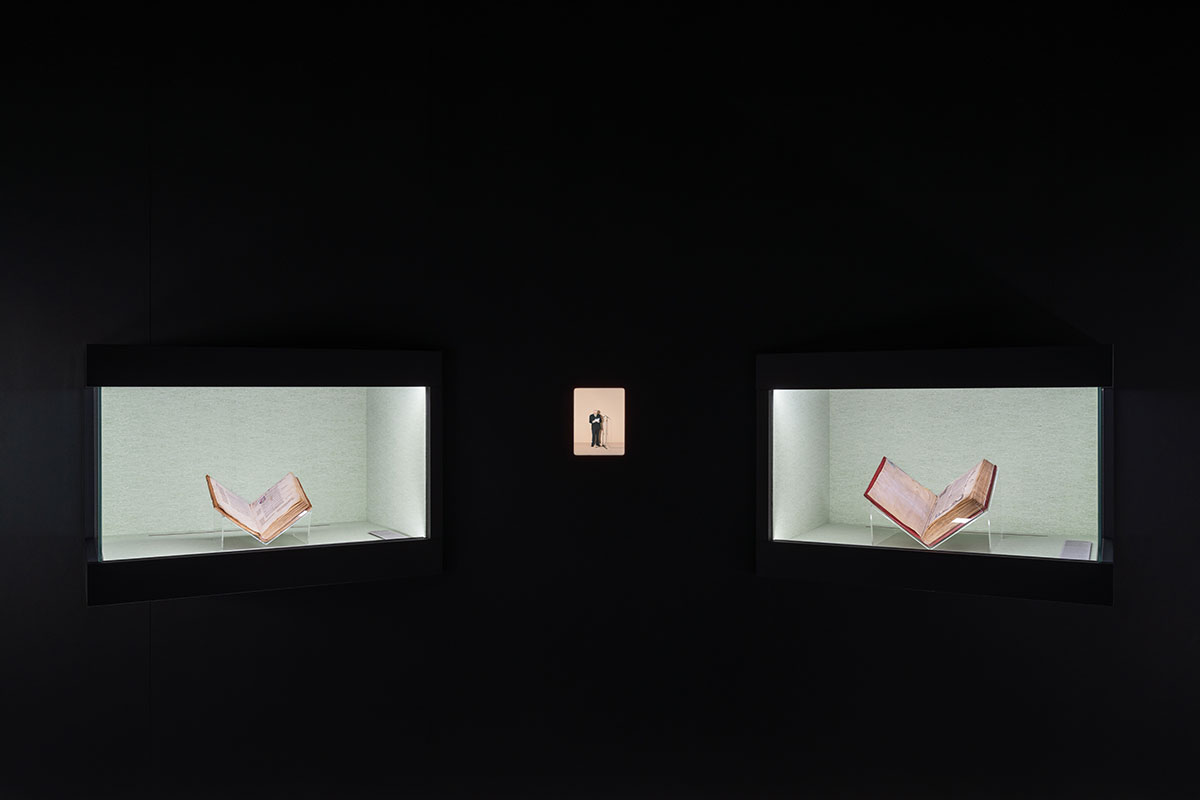

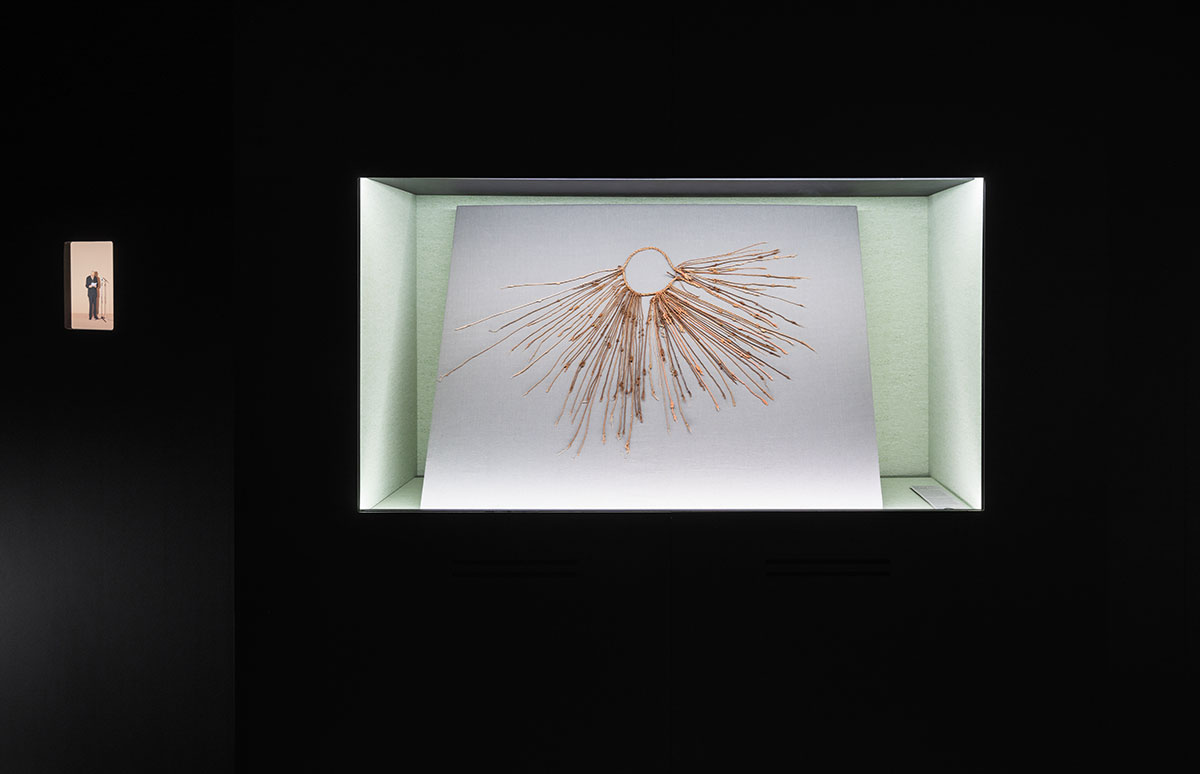

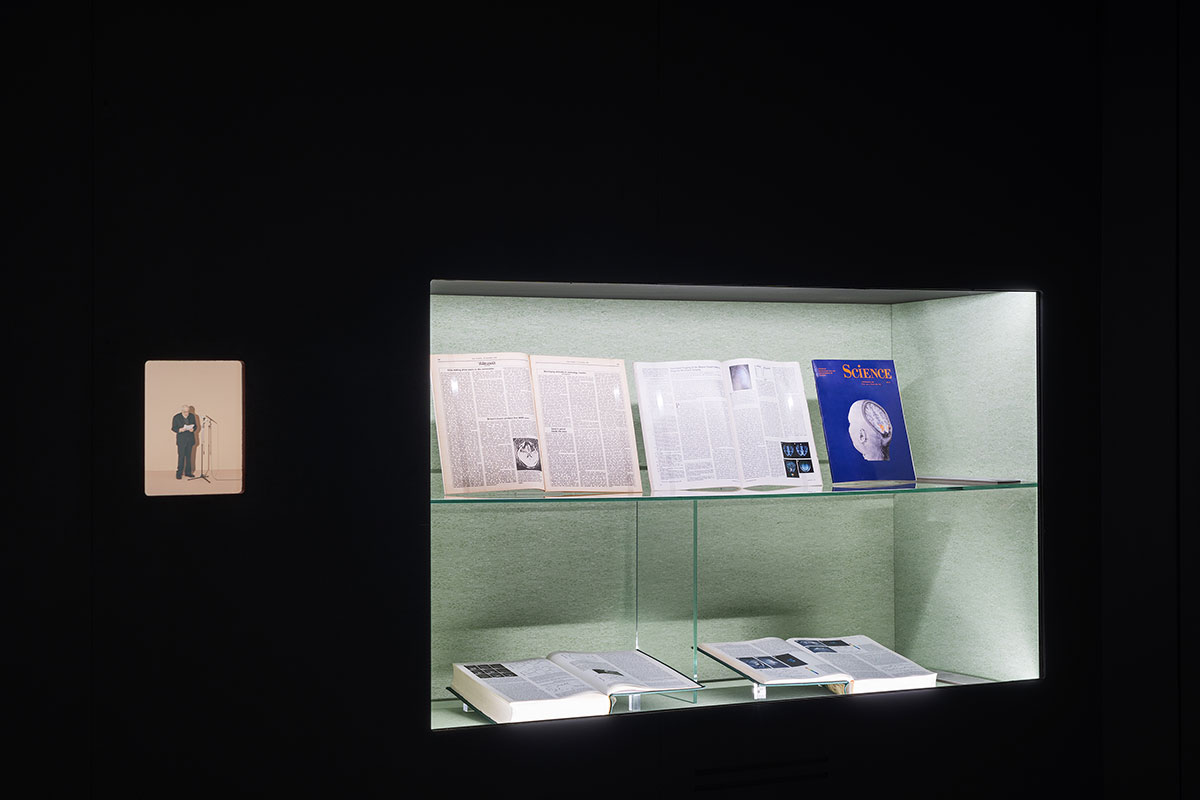

The exhibition “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” curated by Udo Kittelmann in collaboration with Taryn Simon, it is the latest manifestation of “Human Brains”. This project is the result of an intensive investigative process, undertaken since 2018 by Fondazione Prada with the support of a scientific committee, in the field of neuroscientific studies. It serves as a multidisciplinary attempt to understand the human brain, its layered functions, and its centrality to human history. At the center of the ground floor, stadium seating, traditional in medical amphitheaters where live surgeries were given alongside lectures, invites the viewer into the position of an observing student or spectator, with the object of studying the history of neuroscience itself. Online found footage of experiments, surgeries, and discoveries introduce the audience to a sampling of anatomies, mechanisms, and illustrations of the brain as we have come to know it. These videos of neuroimaging, surgical operations and laboratory discoveries include a basement experiment uncovering how we process visual material, an operation seeking the pathways of memory, and an investigation into the neural tributaries of learning. In the adjacent rooms lessons given by scientists and researchers Stefano Cappa, Guido Gainotti, Letizia Leocani, Andrea Moro, Maria Concetta Morrone, and Daniela Perani, focus on the human brain’s ability to see, speak, move, remember, and feel emotions. Here syntax and neural components of language and conscious-ness stand alongside illusion of vision, sensory- motor performance and memory. A labyrinth of vitrines and monitors unfolds across the two floors. Artifacts, documents, paintings, and other historical objects or their copies and facsimiles, encode centuries of attempts to understand the human brain. These are challenged by the words of fiction writers who call them forth, expanding the boundaries of our investigation scope, as well as revealing latent social, political, and personal histories. The vitrines’ objects and extended captions report an ongoing desire to understand the origin and location of thought and the mechanisms of movement and perception, but also the proliferation of brilliant theories, dark practices, and the application of theoretical models for the treatment of physical and mental illness. These artifacts and collected data form an imaginative contract with their assigned writer: a temporary moment of coherence before fictional reinvention. Evolution has embedded in the brain a surprising ability to produce and absorb inaccurate memories. This counterintuitive brain function is an adaptive one that asserts the primacy of the present moment to meaning-making. A 3D copy of two Sumerian cylinders with cuneiform texts reporting the earliest record of a dream (Iraq, 2120–2110 BCE); a papyrus facsimile listing forty-eight medical case histories, named for the American Egyptologist and antiquities dealer Edwin Smith who purchased it in Luxor (17th century BCE); Greek, Latin, Byzantine, Islamic, and Renaissance manuscripts and books—sometimes copies of the original—that have survived and proliferated through their adaptation and replication over time; a semi-circular Andean ceremonial knife used for medical operations and ritual sacrifices (Northern Peru, 13th-15th century); a scale model made by the CNR Laboratories of the anatomical theater at the University of Padua (1595, model 1933); Cerebri Anatome a book on brain anatomy by Thomas Willis, illustrated by architect Christopher Wren (1664); an 19th-century reprint of the Kaishihen, the first recorded dissection of a brain in Japan by physician and surgeon Shinnin Kawaguchi, illustrated by painter and draughtsman Shunmei Aoki (1772); two bronze carvings of the Shiva Nataraja dancing on Apasmara, the demon of ignorance (India, 18th-19th century); Francesco Calenzuoli’s open head wax anatomical model (19th century); original drawings of neurons by Nobel prize winners Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1883–1921); the work of Rita Levi-Montalcini which resulted in the discovery of the Nerve Growth Factor (1951 and 1964); an article published in New Scientist, documenting the first MRI of a human brain (1978); and more are called forth by the writers in the self-same way mem-ories are retrieved, winnowed, and remodeled within the speculative process evolution dictates and fiction recreates. The artifact’s stories in “It Begins with an Idea” were written by international writers to be performed in thirty-two short videos, directed by Taryn Simon and produced by Fondazione Prada for the exhibition, in which renowned audiobook narrator George Guidall reads aloud all the newly commissioned literary texts. One voice is projected into multiple stories, languages, geographies, bodies, and realities: an intractable framework problem foundational both to how the brain works and to how the history of neuroscience has been constructed. While the exhibition’s labyrinth suggests a potential single path, the invitation to hear a story-told reconfigures the visitor’s navigation at every turn. The human brain’s tendency to project itself onto its environment is equaled by its necessity to absorb grounding beliefs and ideas. Brought together here, fiction and history tip each other back and forth in a vital play of certainty and interpretation regarding how stories, and histories, are told and by whom. On the second floor, neuroscientists, psychologists, neurolinguists, and philosophers from five continents are broadcast in an assembly of thirty-two screens. They investigate neuroscientific experiments and their philosophical and ethical dimensions. Like the brain, The Conversation Machine (videos, interviews, and orchestration by Taryn Simon, produced by Fondazione Prada for the exhibition) is a self-organizing system. It responds to itself, continually constructing and assimilating its own order and disorder. In clips excerpted from over 140 hours of interviews, participants appear to listen and respond to each other’s statements. They enter and exit. Objects that refer to their work appear in flashes. Clusters of discussants migrate across the screens. Others sit in sustained, active silence. Like the brain, the conversation morphs according to a logic of prediction and surprise. Attention and distraction maximize and minimize responsiveness in human brains. The “listeners” in the conversation mark this balance while the viewer’s attention is by turns captured, lost, redirected, tested, split, and pulled. Objects, empty chairs, fidgets, speaker and screen changes incorporate distraction—the conductor of attention—directly into the environment. The participants talk about research, experiments, ideas of “me,” survival, biological changes carved by trauma. The brain feeds on mismatch, connections, stimuli. The conversation navigates a history of neuroscientific knowledge-making marked by rigor, breakthrough, and discovery—but also by error, transgression, and uncertainty. It attends also to the continual presence of absences: gaps, missing perspectives, hidden layers. It tracks forces of violence, extinction, and oblivion embedded in our brains alongside creativity, regeneration, and resilience.

Photo: Exhibition view: Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea, Fondazione Prada-Venice, 2022, Photo: Marco Cappelletti Courtesy: Fondazione Prada

Info: Curators: Udo Kittelmann and Taryn Simon, Fondazione Prada, Ca’ Corner della Regina, Santa Croce 2215, Venice, Italy, Duration: 23/4-27/11/2022, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.fondazioneprada.org/