PRESENTATION: Nam June Paik-Super Baroque

Nam June Paik (20/7/1932-29/1/2006), who is commonly hailed as the “father” of new media art for his discoveries in music, video, performance, television broadcast and technological experimentation. On the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Nam June Paik’s birth, the exhibition “Super Baroque” was born of the desire to revisit Paik’s bygone) installations filled with videos and lights. While Paik’s video art is widely known, there are relatively few opportunities to encounter large-scale media installations.

Nam June Paik (20/7/1932-29/1/2006), who is commonly hailed as the “father” of new media art for his discoveries in music, video, performance, television broadcast and technological experimentation. On the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Nam June Paik’s birth, the exhibition “Super Baroque” was born of the desire to revisit Paik’s bygone) installations filled with videos and lights. While Paik’s video art is widely known, there are relatively few opportunities to encounter large-scale media installations.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Nam June Paik Art Center

Nam June Paik took part in the 1993 Venice Biennale and installed a large-scale media work “Sistine Chapel” using 40 projectors, which caused a great sensation. In 1995, he presented “Baroque Laser”, in which he installed large-scale projections and lasers in a baroque church in Germany. All of these works are strongly bound to the specific time and space in which they were embodied. “Sistine Chapel” was made in the high ceiling and large space of the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in the heat of midsummer, while “Baroque Laser” was staged in a quiet and small church on the outskirts of Münster with all the windows closed. In the exhibition “Super Baroque” Nam June Paik Art Center calls the spatial and temporal experience that Paik created by projecting videos directly onto an architectural space as analog immersion. This might have provided a different kind of experience from today’s (perfect but flat) digital immersion generated by large-scale media facades or projection mapping realized with ultra-high resolution digital images. For Paik, a laser is the fastest and most powerful medium for transmitting data and light, and it means endless possibilities of art and technology. Lasers, videos, televisions, CRTs, magnets, candles and the moon, these technologies are other names for Paik. He combined these technologies together to disrupt the flow of time so that we can live not only in the future, but also in the past, in many kinds of the past indeed. Certainly, we can also live in the present sometimes.

In 1995, Nam June Paik decided to create “Baroque Laser” to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the birth of the German Baroque architect Johann Schlaun, and chose the Loreto Chapel built by Schlaun as a place for the work. He accepted the conditions of the chapel that was being used for pilgrims at the time and made Baroque Laser to follow the ‘given architectural, historical, and religious context of Baroque’ in terms of both content and aesthetics. Therefore, Paik closed all the windows of the chapel to darken the place which was flooded with light and let the audience enjoy laser and video projections in silence. The highlight of this exhibition was Paik’s performance in which he climbed up a ladder and used laser crossing the central dome. He put his hands together to gather laser light, and then aligned his fingertips with laser like playing the piano. He also used laser to light a cigarette, and created cigarette smoke to make laser visible spatially. The essence of Baroque Laser was to explore the possibility of laser as a device for projecting three-dimensional images close to a hologram. Paik hung down a curtain made of gauze in front of the sanctuary, projected the video of Merce Cunningham doing a dance by a laser projector in three RGB colors, and created a three-dimensional sense of space revolving around the sanctuary like a hologram. Another key point of Baroque Laser is light. Paik used red laser beams to connect a candle light, the natural light of the past, to a video, the light of the present, and laser, the light of the future. While various technologies that emit light communicate with each other, we travel through the diverse temporalities of technology from the baroque to the present.

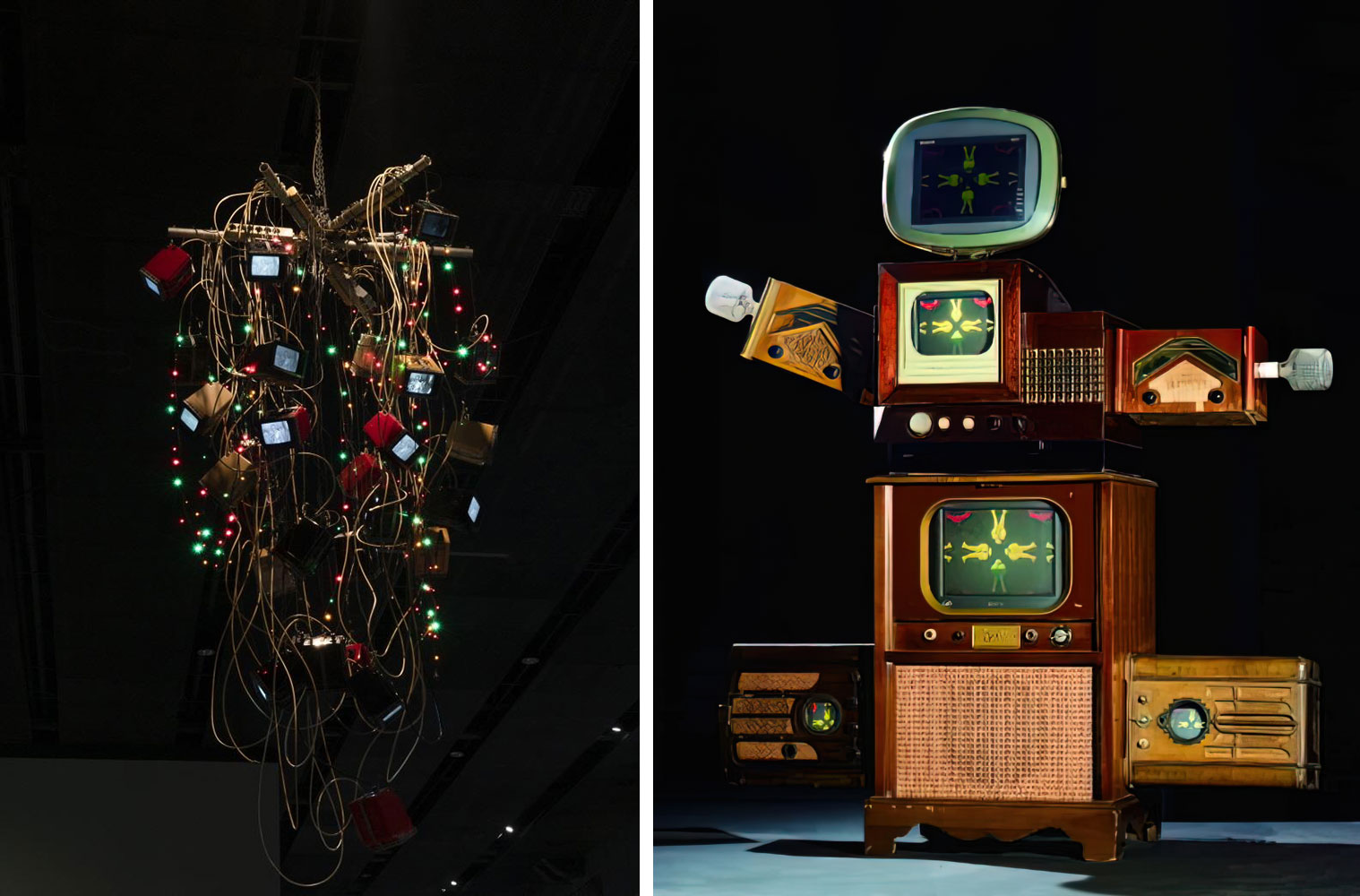

The word ‘chandelier’ comes from the Latin word ‘candelabrum’ which means candle holder. A chandelier is usually set with several glowing candles and sparkling decorations such as crystals around it to spread light beautifully. Therefore, a chandelier decorates a space most luxuriously, and itself symbolizes wealth, achievement, and high social status. Nam June Paik’s first chandelier, which used black-and-white televisions as candles to emit images and lights, and hanging wires and small LED light bulbs as decorations, can be seen as a celebration of our space that has changed by media. What is interesting is that Paik selected Telestar black-and-white CRT monitors produced in the former Soviet Union in “Video Chandelier No. 1” to play animations made with computer graphics, which was the latest technology at the time. Although the monitors were black-and-white, they were wireless portable televisions and groundbreaking in those times. He might have imagined a future where there is no spatial constraint by showing computer graphic images freely moving in virtual spaces in the chandelier with televisions easy to move around. Video Chandelier No. 1 strikes us with old images in black-and-white televisions and the aesthetic of the media, and also shows Paik’s technological imagination that travels beyond time, from the past technology of lighting candles to the latest technology of wireless communication.

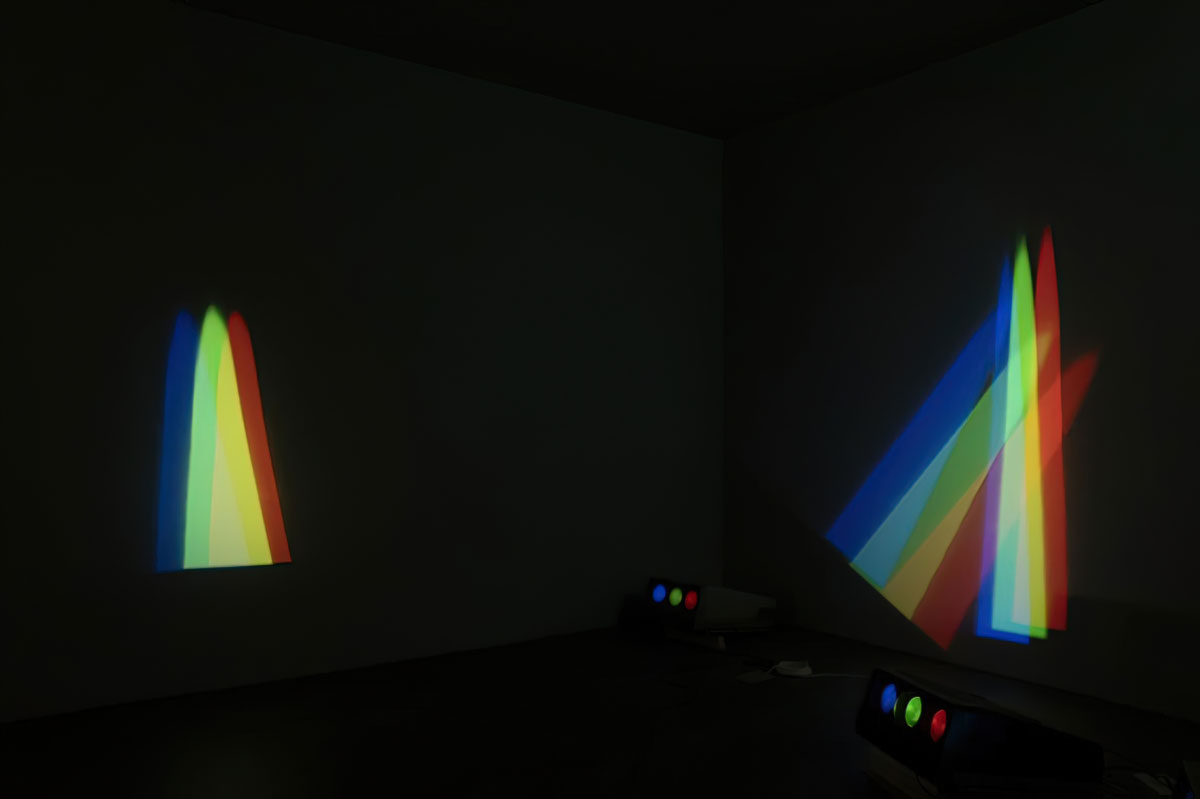

“One Candle” is a work in which a candle is lit and recorded, and then the images are projected on the wall by several CRT projectors. The camera takes the flame of a candle moving along the surrounding air and sends the image signals to projectors in real-time, and the projectors throws immaterial and electronic images on the wall. However, the images projected on the wall spreads in various colors like a spectrum of light. This is due to the technical characteristics of cathode ray tube projectors which were mainly used in the 1990s. A CRT projector has a method of creating screens through cathode ray tubes of three colors – red, green and blue, then merging and transmitting them, and Nam June Paik manipulated it to prevent screens projected from each cathode ray tube from being completely merged. Therefore, images are projected through separate cathode ray tubes, and only overlapping parts of the lights emitted from each tube create colorful lights such as yellow, cyan, and purple. Though the audience does not fully understand the technology which Paik manipulated, they can experience the coexistence of natural light and artificial light generated at the same time. Paik, through the title of One Candle, emphasizes that all these environments started with a single candle that symbolizes past technologies and nature, and now shows the aesthetic of videos and the power of technological media which express the light in a new way.

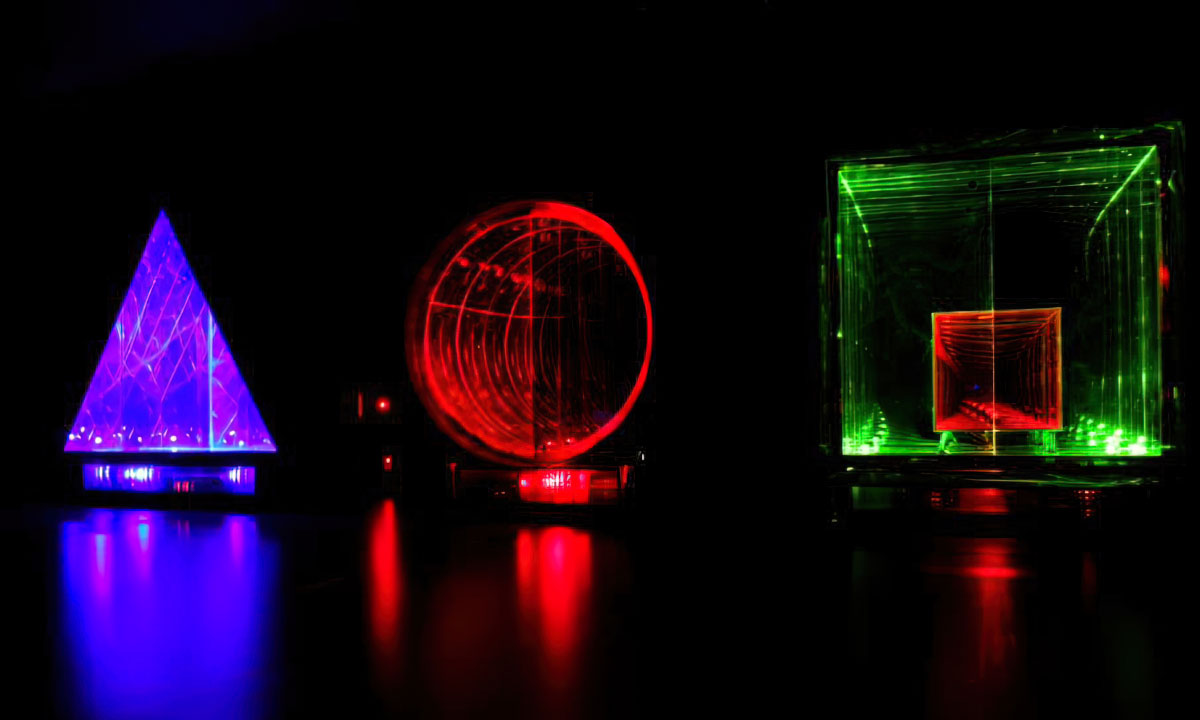

“Three Elements” refers to the combination of Circle, Square and Triangle Nam June Paik produced from 1997 over three years. He often said from around 1995 that he would like to employ laser to give shape to the notion of cheon-ji-in (heaven, earth, and man). It can be assumed that the three geometric forms represent won-bang-gak (circle, square, and triangle) that represents cheon-ji-in in traditional Korean culture. Three Elements is a form of box where mirrors are attached to a wooden frame in each geometric shape. You can look into the box, as its front is a two-way mirror. A colored laser beam is shot through a small hole to a prism that is rotated by a speed-controlled DC motor. Laser beams in three primary colors of red, blue and green are refracted by the prism and reflected on the mirror. Due to the constantly rotating prism those beams continuously and dynamically move with a high velocity in different angles, which imbue the inner space with a sense of infinite depth. Paik himself called the period of time in which he drew on laser as “post video.” More than anything else, Paik was preoccupied with the issue of light, and broadening his realm of media as demanded by a new era after video, he ended up with laser. He anticipated that in the history of moving images, the notions of time and space had been fundamentally changed by video and television; and it was laser for him that could transform them once again.

“Candle TV” is a work in which the inside of an old television is emptied and a candle is lit there. Although ordinary electronic machines hide their complex technologies in a black box to make them incomprehensible and inaccessible, Nam June Paik rather exposed their technical structures for the audience to understand his works intuitively. With its clear structure, the work evokes a strong poetic association in which the symbolism of candles contrasts with technology. The tension and confrontation are created between light and darkness, meditation and technique, and the sacredness of candlelight and the vulgarity of popular culture. Candle TV reveals inversely the electronic and immaterial properties of a television by replacing the electric light of a television with a candle that produces light by burning substances. If the candle burns out, someone has to replace it with a new one and light it again instead of turning on the television. This tells the essence of technology that it should be human-oriented while showing that constantly developing new technology is ironically replaced by a candle light, which is an old technology.

“Sistine Chapel” was first exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1993 when Nam June Paik was awarded the Golden Lion as the representative of the German Pavilion. He built a scaffold in the center of the high-ceilinged German Pavilion and suspended projectors to project images on the walls. This structure reminds us of the historical account that Michelangelo painted the murals of Sistine Chapel on a 20-meter-high scaffold. The role of the painter, who painstakingly painted murals on the scaffold, has been replaced by machines that instantaneously project numerous images. Sistine Chapel gives an impression that various images such as a shoal of fish, the American flag, and Joseph Beuys are played at random. Paik actually made it so that the projected positions of the four-channel images composed of various video footages were continuously changed. Through this, he multiplied disorderly images like viruses and decorated the immutable architectural space with moving images. Therefore, as soon as the audience enters the space, they found themselves buried under the sudden pouring of images and sounds. The sensation experienced in Sistine Chapel is different from today’s digital immersion that perfectly replicates a reality and overlays it on a screen. While digital immersion creates the illusion of being in another space, Sistine Chapel awakens us by disturbing our senses and breaking narrative order. It is a performance that cannot be reduced to digitized data or reproduced repeatedly, and is a (existential/perfect) time and space that only those present there at that moment can experience.

Photo: Nam June Paik, Three Elements, 1999, left to Circle: 287×234×122cm, 1 laser, wooden frame, mirror, one-way mirror plexiglass, optical system, 2 prisms, 2 motors, power supply, fog machine, Square: 309×246×122cm, 2 lasers, wooden frame, mirror, one-way mirror plexiglass, optical system, 3 prisms, 3 motors, power supply, fog machine, Triangle: 325×375×122cm, 1 laser, wooden frame, mirror, one-way mirror plexiglass, optical system, 2 prisms, 2 motors, power supply, fog machine, Nam June Paik Art Center collection, ⓒNam June Paik Estate

Info: Curator: Lee Sooyoung, Nam June Paik Art Center, 10 Paiknamjune-ro, Giheung-gu, Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, Duration: 20/7/2022-24/1/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, https://njp.ggcf.kr/

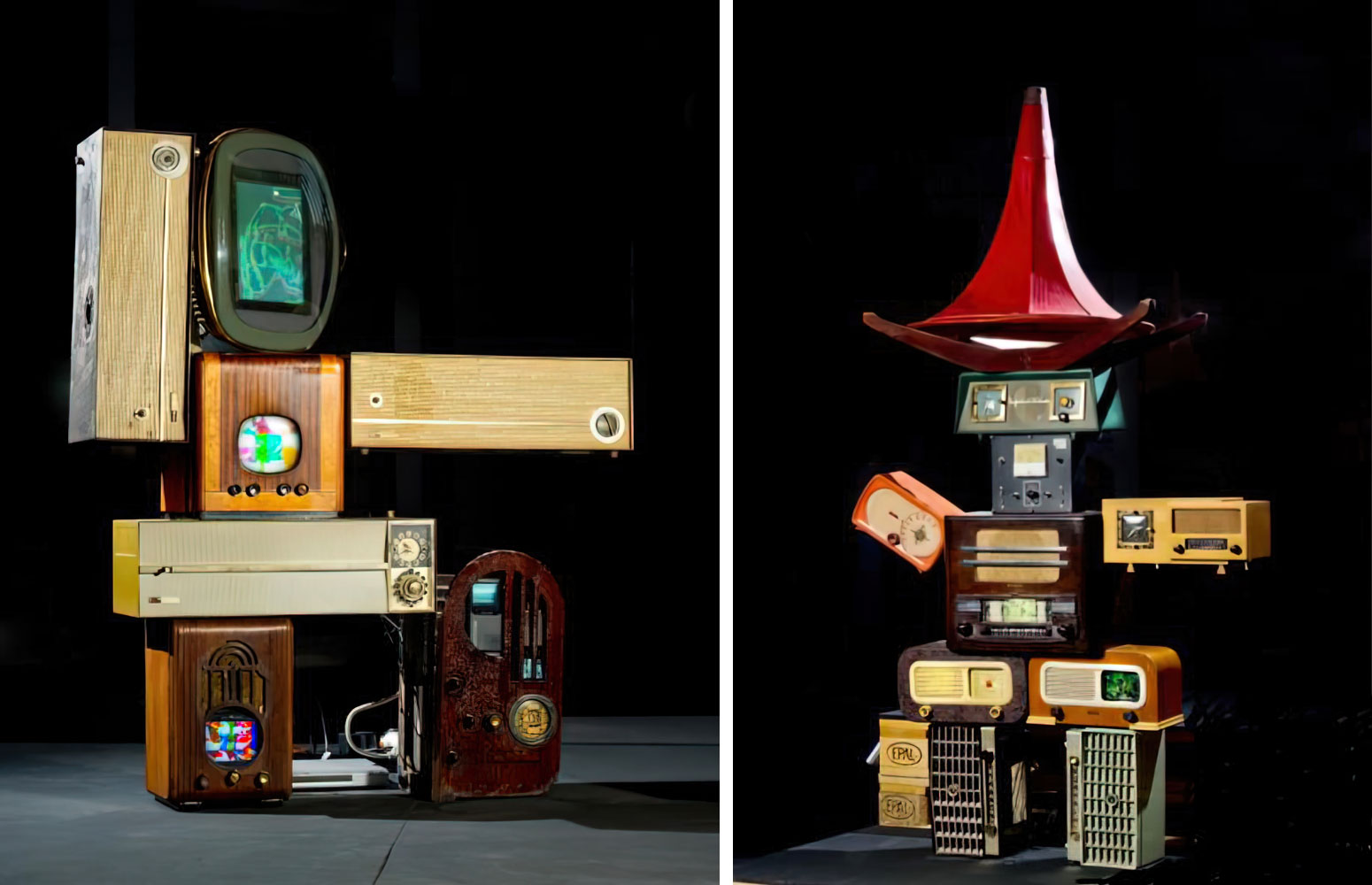

Right: Nam June Paik, Charlie Chaplin, 2002, 185×152×56cm, 4 CRT TV sets, 1 LCD TV set, 3 vacuum-tube TV cases, 4 vacuum-tube radio cases, Nam June Paik Art Center collection, © Nam June Paik Estate

Right: Nam June Paik, Schubert, 2002, 183×108×61cm, 3 LCD TV sets, 9 vacuum-tube radio cases, 1 gramophone speaker, 1 video distributor, single-channel video, color, silent, DVD, Nam June Paik Art Center collection, ⓒ Nam June Paik Estate